Contents

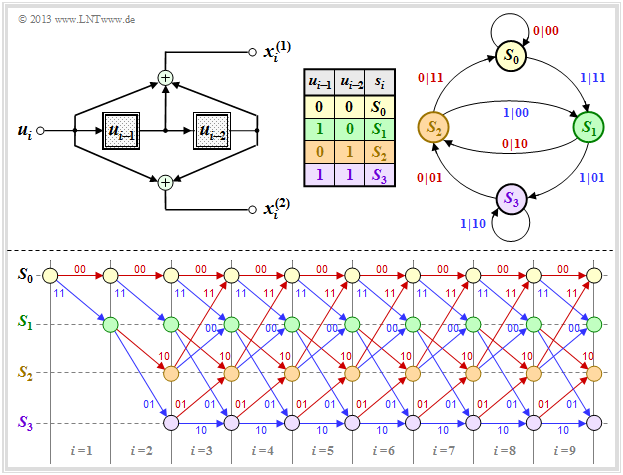

State definition for a memory register

A convolutional encoder can also be understood as an automaton with a finite number of states. This number results from the number m of memory elements to 2m.

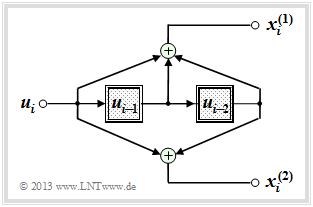

In this chapter we mostly start from the drawn convolutional encoder, which is characterized by the following parameters:

- k=1, n=2 ⇒ code rate R=1/2,

- Memory m=2 ⇒ influence length ν=m+1=3,

- Transfer function matrix in octal form (7,5):

- G(D)=(1+D+D2, 1+D2).

The encoded sequence x_i=(x(1)i, x(2)i) at time i depends not only on the information bit ui but also on the content (ui−1, ui−2) of the memory.

- There are 2m=4 possibilities for this, namely the states S0, S1, S2, S3.

- Let the register state Sμ be defined by the index

- μ=ui−1+2⋅ui−2,general:μ=m∑l=12l−1⋅ui−l.

To avoid confusion, we distinguish in the following by upper or lower case letters:

- the possible states Sμ with the indices 0≤μ≤2m−1,

- the current states si at the times i=1, 2, 3, ...

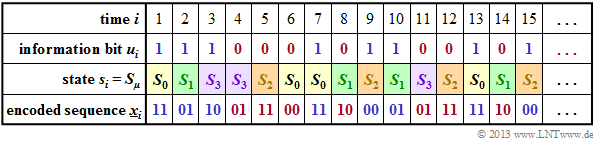

Example 1: The graph shows for the convolutional encoder sketched above

- the information sequence u_=(u1,u2,... )

⇒ information bits ui,

- the current states at times i

⇒ si∈{S0, S1, S2, S3},

- the 2–bit sequences x_i=(x(1)i, x(2)i)

⇒ encoding the information bit ui.

For example, you can see from this illustration (the colors are to facilitate the transition to later graphics):

- At time i=5 ⇒ ui−1=u4=0, ui−2=u3=1 holds. That is, the automat is in state s5=S2.

- With the information bit ui=u5=0, the encoded sequence x_5=(11) is obtained.

- The state for time i=6 results from ui−1=u5=0 and ui−2=u4=0 to s6=S0.

- Because of u6=0 ⇒ x_6=(00) is output and the new state s7 is again S0.

- At time i=12 the encoded sequence x_12=(11) is output because of u12=0 as at time i=5.

- Here, one passes from state s12=S2 to state s13=S0 .

- In contrast, at time i=9 the encoded sequence x_9=(00) is output and state s9=S2 is followed by s10=S1.

- The same is true for i=15. In both cases, the current information bit is ui=1.

Conclusion: From this example it can be seen that the encoded sequence x_i at time i depends solely on

- the current state si=Sμ (0≤μ≤2m−1), as well as

- the current information bit ui.

- Similarly, the successor state si+1 is determined by si and ui alone.

- These properties are considered in the so-called "state transition diagram" in the next section.

Representation in the state transition diagram

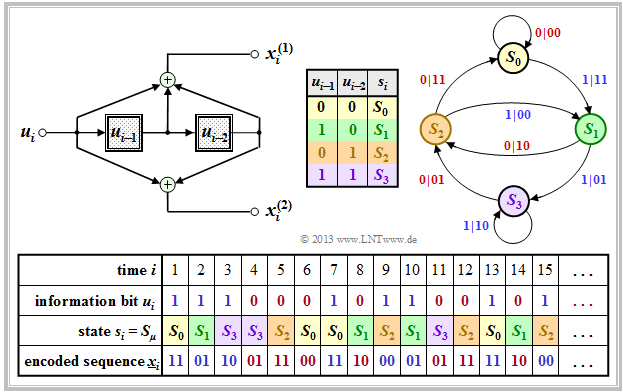

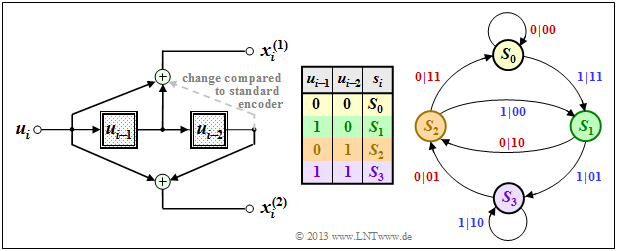

The graph shows the state transition diagram for the (n=2, k=1, m=2) convolutional encoder.

- This diagram provides all information about this special convolutional encoder in compact form.

- The color scheme is aligned with the sequential representation in the previous section.

- For the sake of completeness, the derivation table is also given again.

- The 2m+k transitions are labeled "ui | x_i".

For example, it can be read:

- The information bit ui=0 (indicated by a red label) takes you from state si=S1 to state si+1=S2 and the two code bits are x(1)i=1, x(2)i=0.

- With the information bit ui=1 (blue label) in the state si=S1 the code bits result in x(1)i=0, x(2)i=1, and one arrives at the new state si+1=S3.

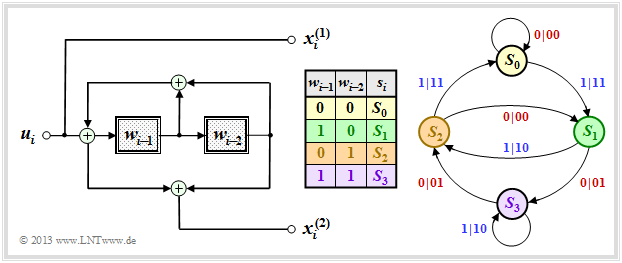

We now consider another systematic encoder with same parameters:

- n=2, k=1, m=2.

This is the equivalent systematic representation of our standard convolutional encoder, also referred to as "recursive systematic convolutional encoder".

Compared to the upper state transition diagram A, one can see the following differences:

- Since the earlier information bits ui−1 and ui−2 are not stored, here the states si=Sμ are related to the processed quantities wi−1 and wi−2, where wi=ui+wi−1+wi−2 holds.

- Since this code is also systematic ⇒ x(1)i=ui. The derivation of the second code bits x(2)i can be found in "Exercise 3.5". It is a recursive filter, as described in the "Filter structure with fractional–rational transfer function" section.

Conclusion: The comparison of the graphics shows that a similar state transition diagram is obtained for both encoders:

- The structure of the state transition diagram is determined solely by the parameters m and k .

- The number of states is 2m⋅k and 2k arrows go from each state.

- You also get from each state si∈{S0, S1, S2, S3} to the same successor states si+1.

- A difference exists solely with respect to the encoded sequences output, where in both cases x_i∈{00, 01, 10, 11} applies.

Representation in the trellis diagram

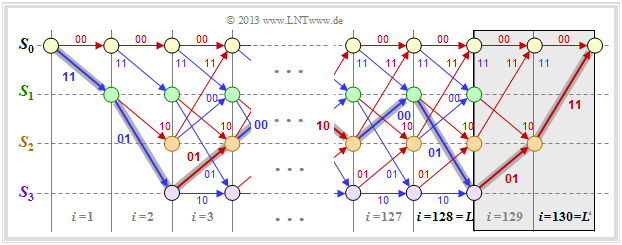

One gets from the state transition diagram to the so-called "trellis diagram" (short: trellis) by additionally considering a time component ⇒ control variable i. The following graph contrasts both diagrams for "our standard convolutional encoder". The bottom illustration has a resemblance to a "garden trellis" – assuming some imagination.

Further is to be recognized on the basis of this diagram:

- Since all memory registers are preallocated with zeros, the trellis always starts from the state s1=S0. At the next time (i=2) only the two states S0 and S1 are possible.

- From time i=m+1=3 the trellis has exactly the same appearance for each transition from si to si+1. Each state Sμ is connected to a successor state by a red arrow (ui=0) and a blue arrow (ui=1).

- Versus a "code tree" that grows exponentially with each time step i – see for example section "Error sizes and total error sizes" in the book "Digital Signal Transmission" – here the number of nodes (i.e. possible states) is limited to 2m .

- This pleasing property of any trellis diagram is also used by the Viterbi algorithm for efficient maximum likelihood decoding of convolutional codes.

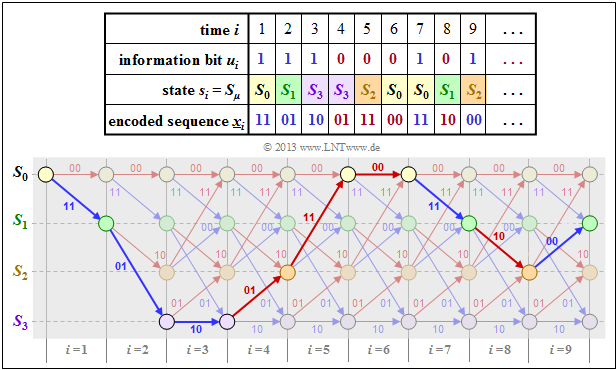

The following example is to show that there is a "1:1" mapping between the string of encoded sequences x_i and the paths through the trellis diagram.

- Also the information sequence u_ can be read from the selected trellis path based on the colors of the individual branches.

- A red branch stands for the information bit ui=0, a blue one for ui=1.

Example 2: In the former Example 1 the encoded sequence x_ was derived

- for our rate 1/2 standard convolutional encoder with memory m=2 and

- the information sequence u_=(1,1,1,0,0,0,1,0,1, . ..)

The table on the right shows the result for i≤9 once again. The trellis diagram is drawn below. You can see:

- The selected path through the trellis is obtained by lining up red and blue arrows representing the possible information bits ui∈{0, 1} .

- This statement is true for any rate 1/n convolutional code. For a code with k>1 there would be 2k different colored arrows.

- For a rate 1/n convolutional code, the arrows are labeled with the code words x_i=(x(1)i, ... , x(n)i) which are derived from the information bit ui and the current register states si.

- For n=2 there are only four possible code words, namely 00, 01, 10 and 11.

- In vertical direction, one recognizes from the trellis the register states Sμ. Given a rate k/n convolutional code with memory order m there are 2k⋅m different states.

- In the present example (k=1, m=2) these are the states S0, S1, S2 and S3.

Definition of the free distance

An important parameter of linear block codes is the minimum Hamming distance between any two code words x_ and x_′:

- dmin(C)=min

- Due to linearity, the zero word \underline{0} also belongs to each block code. Thus d_{\rm min} is identical to the minimum \text{Hamming weight} w_{\rm H}(\underline{x}) of a code word \underline{x} ≠ \underline{0}.

- For convolutional codes, however, the description of the distance ratios proves to be much more complex, since a convolutional code consists of infinitely long and infinitely many encoded sequences. Therefore we define here instead of the minimum Hamming distance:

\text{Definition:}

- The »free distance« d_{\rm F} of a convolutional code is equal to the number of bits in which any two encoded sequences \underline{x} and \underline{x}\hspace{0.03cm}' differ (at least).

- In other words: The free distance is equal to the minimum Hamming distance between any two paths through the trellis.

Since convolutional codes are linear, we can also use the infinite zero sequence as a reference sequence: \underline{x}\hspace{0.03cm}' = \underline{0}. Thus, the free distance d_{\rm F} is equal to the minimum Hamming weight (number of "ones") of a encoded sequence \underline{x} ≠ \underline{0}.

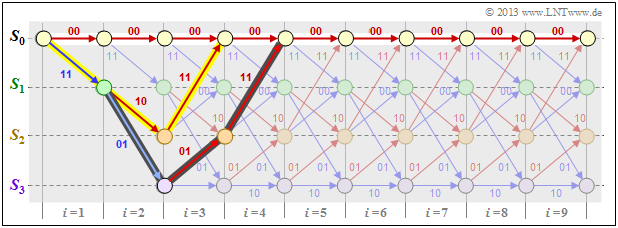

\text{Example 3:} We consider the null sequence \underline{0} (marked with white filled circles) as well as two other encoded sequences \underline{x} and \underline{x}\hspace{0.03cm}' (with yellow and dark background, respectively) in our standard trellis and characterize these sequences based on the state sequences:

- \underline{0} =\left ( S_0 \rightarrow S_0 \rightarrow S_0\rightarrow S_0\rightarrow S_0\rightarrow \hspace{0.05cm}\text{...} \hspace{0.05cm}\right)

- \hspace{0.3cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} \underline{0} = \left ( 00, 00, 00, 00, 00,\hspace{0.05cm} \text{...} \hspace{0.05cm}\right) \hspace{0.05cm},

- \ \underline{x} =\left ( S_0 \rightarrow S_1 \rightarrow S_2\rightarrow S_0\rightarrow S_0\rightarrow \hspace{0.05cm}\text{...} \hspace{0.05cm}\right)

- \hspace{0.3cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}\underline{x} == \left ( 11, 10, 11, 00, 00,\hspace{0.05cm} \text{...} \hspace{0.05cm}\right) \hspace{0.05cm},

- \underline{x}\hspace{0.03cm}' = \left ( S_0 \rightarrow S_1 \rightarrow S_3\rightarrow S_2\rightarrow S_0\rightarrow \hspace{0.05cm}\text{...} \hspace{0.05cm}\right)

- \hspace{0.3cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}\underline{x}\hspace{0.03cm}' = \left ( 11, 01, 01, 11, 00,\hspace{0.05cm} \text{...} \hspace{0.05cm}\right) \hspace{0.05cm}.

One can see from these plots:

- The free distance d_{\rm F} = 5 is equal to the Hamming weight w_{\rm H}(\underline{x}).

- No sequence other than the one highlighted in yellow differs from \underline{0} by less than five bits. For example w_{\rm H}(\underline{x}') = 6.

- In this example, the free distance d_{\rm F} = 5 also results as the Hamming distance between the sequences \underline{x} and \underline{x}\hspace{0.03cm}', which differ in exactly five bit positions.

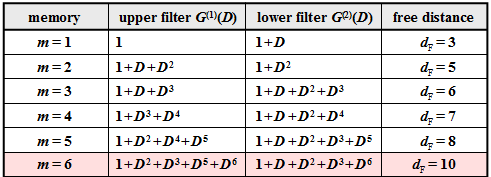

The larger the free distance d_{\rm F}, the better is the "asymptotic behavior" of the convolutional encoder.

- For the exact error probability calculation, however, one needs the exact knowledge of the \text{weight enumerator function} just as for the linear block codes.

- This is given for the convolutional codes in detail only in the chapter "Distance Characteristics and Error Probability Bounds".

At the outset, just a few remarks:

- The free distance d_{\rm F} increases with increasing memory m provided that one uses appropriate polynomials for the transfer function matrix \mathbf{G}(D) .

- In the table for rate 1/2 convolutional codes, the n = 2 polynomials are given together with the d_{\rm F} value.

- Of greater practical importance is the "industry standard code" with m = 6 ⇒ 64 states and the free distance d_{\rm F} = 10 (in the table this is highlighted in red).

The following example shows the effects of using unfavorable polynomials.

\text{Example 4:} In \text{Example 3} it was shown that our standard convolutional encoder (n = 2, \ k = 1, \ m = 2) has the free distance d_{\rm F} = 5. This is based on the transfer function matrix \mathbf{G}(D) = (1 + D + D^2, \ 1 + D^2), as shown in the model (without red deletion).

Using \mathbf{G}(D) = (1 + D, \ 1 + D^2) ⇒ red change, the state transition diagram changes from the \text{state transition diagram $\rm A$} little at first glance. However, the effects are serious:

- The free distance is no longer d_{\rm F} = 5, but d_{\rm F} = 3, where the encoded sequence \underline{x} = (11, \ 01, \ 00, \ 00, \text{. ..}) with only three ones belonging to the information sequence \underline{u} = \underline{1} = (1, \ 1, \ 1, \ 1, \ \text{...}).

- That is: By only three transmission errors at positions 1, 2, and 4, one falsifies the "one sequence" (\underline{1}) into the "zero sequence" (\underline{0}) and thus produces infinitely many decoding errors in state S_3.

- A convolutional encoder with these properties is called "catastrophic". The reason for this extremely unfavorable behavior is that here the two polynomials 1 + D and 1 + D^2 are not divisor-remote.

Terminated convolutional codes

In the theoretical description of convolutional codes, one always assumes information sequences \underline{u} and encoded sequences \underline{x} that are by definition infinite in length.

- On the other hand, in practical applications e.g. \text{GSM} and \text{UMTS}, one always uses an information sequence of finite length L.

- For a rate 1/n convolutional code, the encoded sequence then has at least length n \cdot L.

The graph (without the gray background) shows the trellis of our standard rate 1/2 convolutional code at binary input sequence \underline{u} of finite length L = 128.

- Thus the encoded sequence \underline{x} has length 2 \cdot L = 256.

- However, due to the undefined final state, a complete maximum likelihood decoding of the transmitted sequence is not possible.

- Since it is not known which of the states S_0, \ \text{...} \ , \ S_3 would occur for i > L, the error probability will be (somewhat) larger than in the limiting case L → ∞.

- To prevent this, the convolutional code is terminated as shown in the diagram: You add m = 2 zeros to the L = 128 information bits ⇒ L' = 130.

- This results, for example, for the color highlighted path through the trellis:

- \underline{x}' = (11\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 01\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 01\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 00 \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} \text{...}\hspace{0.1cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 10\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm}00\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 01\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 01\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 11 \hspace{0.05cm} )

- \Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}\underline{u}' = (1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1 \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} \text{...}\hspace{0.1cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm}1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0 \hspace{0.05cm} ) \hspace{0.05cm}.

The trellis now ends always (independent of the data) in the defined final state S_0; one thus achieves the best possible error probability according to maximum likelihood.

- However, the improvement in error probability comes at the cost of a lower code rate.

- For L \gg m this loss is only small. In the considered example, instead of R = 0.5 with termination the code rate results in

- R\hspace{0.05cm}' = 0.5 \cdot L/(L + m) \approx 0.492.

Punctured convolutional codes

\text{Definition:}

- We assume a convolutional code of rate R_0 = 1/n_0 which we call "mother code".

- If one deletes some bits from its encoded sequence according to a given pattern, it is called a »punctured convolutional code« with code rate R > R_0.

The puncturing is done using the puncturing matrix \mathbf{P} with the following properties:

- The row number is n_0, the column number is equal to the puncturing period p, which is determined by the desired code rate.

- The n_0 \cdot p matrix elements P_{ij} are binary (0 or 1).

- If P_{ij} = 1 the corresponding code bit x_{ij} is taken, if P_{ij} = 0 not.

- The rate of the punctured code is equal to the quotient of the puncturing period p and the number N_1 of ones in the \mathbf{P} matrix.

One can usually find favorably punctured convolutional codes only by means of computer-aided search. Here, a punctured convolutional code is said to be favorable if it has

- the same memory order m as the parent code, and also the total influence length is the same in both cases: \nu = m + 1,

- a free distance d_{\rm F} as large as possible which is of course smaller than that of the mother code.

\text{Example 5:} Starting from our \text{rate 1/2 standard code} with parameters n_0 = 2 and m = 2, we obtain with the puncturing matrix

- {\boldsymbol{\rm P} } = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 1 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} p = 3\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}N_1 = 4

a punctured convolutional code of rate R = p/N_1 = 3/4.

We consider the following constellation for this purpose:

- Information sequence: \hspace{2.5cm} \underline{u} = (1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, \ \text{...}\hspace{0.03cm}),

- encoded sequence without puncturing: \hspace{0.35cm} \underline{x} = (11, 1 \color{grey}{0}, \color{gray}{1}1, 11, 0\color{gray}{1}, \color{gray}{0}1, \ \text{...}\hspace{0.03cm}),

- encoded sequence with puncturing: \hspace{0.90cm} \underline{x}\hspace{0.05cm}' = (11, 1\_, \_1, 11, 0\_, \_1, \ \text{...}\hspace{0.03cm}),

- received sequence without errors: \hspace{0.58cm} \underline{y} = (11, 1\_, \_1, 11, 0\_, \_1, \ \text{...}\hspace{0.03cm}),

- modified received sequence: \hspace{1.4cm} \underline{y}\hspace{0.05cm}' = (11, 1\rm E, E1, 11, 0E, E1, \ \text{...}\hspace{0.03cm}).

Note:

- So each punctured bit in the received sequence \underline{y} (marked by an underscore) is replaced by an "Erasure" \rm (E), see "Binary Erasure Channel".

- Such an erasure created by the puncturing is treated by the decoder in the same way as an erasure by the channel.

- Of course, the puncturing increases the error probability. This can already be seen from the fact that the free distance decreases to d_{\rm F} = 3 after the puncturing.

- In contrast, the mother code has the free distance d_{\rm F} = 5.

For example, puncturing is used in the so-called \text{RCPC codes} ("rate compatible punctured convolutional codes"). More about this in "Exercise 3.8".

Exercises for the chapter

Exercise 3.6: State Transition Diagram

Exercise 3.6Z: Transition Diagram at 3 States

Exercise 3.7: Comparison of Two Convolutional Encoders

Exercise 3.7Z: Which Code is Catastrophic?

Exercise 3.8: Rate Compatible Punctured Convolutional Codes