Difference between revisions of "Aufgaben:Exercise 2.3: Reducible and Irreducible Polynomials"

| (27 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{quiz-Header|Buchseite= | + | {{quiz-Header|Buchseite=Channel_Coding/Extension_Field}} |

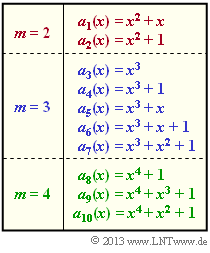

| − | [[File:P_ID2503__KC_A_2_3.png|right|frame| | + | [[File:P_ID2503__KC_A_2_3.png|right|frame|Polynomials of degree $m = 2$, $m = 3$, $m = 4$]] |

| − | + | Important prerequisites for understanding channel coding are knowledge of polynomial properties. | |

| + | |||

| + | In this exercise we consider polynomials of the form | ||

:$$a(x) = a_0 + a_1 \cdot x + a_2 \cdot x^2 + \hspace{0.1cm}... \hspace{0.1cm} + a_m \cdot x^{m} | :$$a(x) = a_0 + a_1 \cdot x + a_2 \cdot x^2 + \hspace{0.1cm}... \hspace{0.1cm} + a_m \cdot x^{m} | ||

\hspace{0.05cm},$$ | \hspace{0.05cm},$$ | ||

| − | + | *where for the coefficients $a_i ∈ {\rm GF}(2) = \{0, \, 1\}$ holds $(0 ≤ i ≤ m)$ | |

| + | |||

| + | *and the highest coefficient is always assumed to $a_m = 1$. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | One refers to $m$ as the "degree" of the polynomial. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Adjacent ten polynomials are given where the polynomial degree is either | ||

| + | *$m = 2$ (red font), | ||

| + | *$m = 3$ (blue font) or | ||

| + | *$m = 4$ (green font). | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | A polynomial $a(x)$ is called <b>reducible</b> if it can be represented as the product of two polynomials $p(x)$ and $q(x)$ of lower degree: | ||

:$$a(x) = p(x) \cdot q(x)$$ | :$$a(x) = p(x) \cdot q(x)$$ | ||

| − | + | If this splitting is not possible, that is, if for the polynomial | |

:$$a(x) = p(x) \cdot q(x) + r(x)$$ | :$$a(x) = p(x) \cdot q(x) + r(x)$$ | ||

| − | + | with a residual polynomial $r(x) ≠ 0$ holds, then the polynomial is called '''irreducible'''. Such irreducible polynomials are of special importance for the description of error correction methods. | |

| − | + | ⇒ The proof that a polynomial $a(x)$ of degree $m$ is irreducible requires several polynomial divisions $a(x)/q(x)$, where the degree of the respective divisor polynomial $q(x)$ is always smaller than $m$. Only if all these divisions $($modulo $2)$ always yield a remainder $r(x) ≠ 0$ it is proved that $a(x)$ is indeed an irreducible polynomial. | |

| − | + | ⇒ This exact proof is very complex. Necessary conditions for $a(x)$ to be an irreducible polynomial at all are the two conditions $($in nonbinary approach "$x=1$" would have to be replaced by "$x≠0$"$)$: | |

* $a(x = 0) = 1$, | * $a(x = 0) = 1$, | ||

| + | |||

* $a(x = 1) = 1$. | * $a(x = 1) = 1$. | ||

| − | + | Otherwise, one could write for the polynomial under investigation: | |

| − | :$$a(x) = q(x) \cdot x \hspace{0.5cm}{\rm | + | :$$a(x) = q(x) \cdot x \hspace{0.5cm}{\rm resp.}\hspace{0.5cm}a(x) = q(x) \cdot (x+1)\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ |

| − | + | The above conditions are necessary, but not sufficient, as the following example shows: | |

:$$a(x) = x^5 + x^4 +1 \hspace{0.3cm} \Rightarrow\hspace{0.3cm}a(x = 0) = 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}a(x = 1) = 1 | :$$a(x) = x^5 + x^4 +1 \hspace{0.3cm} \Rightarrow\hspace{0.3cm}a(x = 0) = 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}a(x = 1) = 1 | ||

\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | \hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| − | + | Nevertheless, this polynomial is reducible: | |

:$$a(x) = (x^3 + x +1)(x^2 + x +1) \hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | :$$a(x) = (x^3 + x +1)(x^2 + x +1) \hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | Hint: This exercise belongs to the chapter [[Channel_Coding/Extension_Field| "Extension field"]]. | ||

| − | === | + | |

| + | |||

| + | ===Questions=== | ||

<quiz display=simple> | <quiz display=simple> | ||

| − | { | + | {How many polynomial divisions $(N_{\rm D})$ are required to prove exactly that a ${\rm GF}(2)$ polynomial $a(x)$ of degree $m$ is irreducible? |

| + | |type="{}"} | ||

| + | $m = 2 \text{:} \hspace{0.35cm} N_{\rm D} \ = \ ${ 2 3% } | ||

| + | $m = 3 \text{:} \hspace{0.35cm} N_{\rm D} \ = \ ${ 6 3% } | ||

| + | $m = 4 \text{:} \hspace{0.35cm} N_{\rm D} \ = \ ${ 14 3% } | ||

| + | |||

| + | {Which of the degree–2 polynomials are irreducible? | ||

|type="[]"} | |type="[]"} | ||

| − | + | + | - $a_1(x) = x^2 + x$, |

| − | + | + $a_2(x) = x^2 + x + 1$. | |

| − | { | + | {Which of the degree–3 polynomials are irreducible? |

| − | |type=" | + | |type="[]"} |

| − | $ | + | - $a_3(x) = x^3$, |

| + | - $a_4(x) = x^3 + 1$, | ||

| + | - $a_5(x) = x^3 + x$, | ||

| + | + $a_6(x) = x^3 + x + 1$, | ||

| + | + $a_7(x) = x^3 + x^2 + 1$. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {Which of the degree–4 polynomials are irreducible? | ||

| + | |type="[]"} | ||

| + | - $a_8(x) = x^4 + 1$, | ||

| + | + $a_9(x) = x^4 + x^3 + 1$, | ||

| + | - $a_{10}(x) = x^4 + x^2 + 1$. | ||

</quiz> | </quiz> | ||

| − | === | + | ===Solution=== |

{{ML-Kopf}} | {{ML-Kopf}} | ||

| − | '''(1)''' | + | '''(1)''' The polynomial $a(x) = a_0 + a_1 \cdot x + a_2 \cdot x^2 + \hspace{0.1cm}... \hspace{0.1cm} + a_m \cdot x^{m}$ |

| − | '''(2)''' | + | *with $a_m = 1$ |

| − | '''(3)''' | + | |

| − | '''(4)''' | + | *and given coefficients $a_0, \ a_1, \hspace{0.05cm}\text{ ...} \hspace{0.1cm} , \ a_{m-1}$ $(0$ or $1$ in each case$)$ |

| − | + | ||

| + | |||

| + | is irreducible if there is no single polynomial $q(x)$ such that the modulo $2$ division $a(x)/q(x)$ yields no remainder. The degree of all divisor polynomials $q(x)$ to be considered is at least $1$ and at most $m-1$. | ||

| + | * For $m = 2$ two polynomial divisions $a(x)/q_i(x)$ are necessary, namely with | ||

| + | :$$q_1(x) = x \hspace{0.5cm}{\rm and}\hspace{0.5cm}q_2(x) = x+1 | ||

| + | \hspace{0.3cm} \Rightarrow\hspace{0.3cm}N_{\rm D}\hspace{0.15cm}\underline{= 2} | ||

| + | \hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| + | * For $m = 3$ there are already $N_{\rm D} \ \underline{= 6}$ divisor polynomials, namely besides $q_1(x) = x$ and $q_2(x) = x + 1$ also | ||

| + | :$$q_3(x) = x^2\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}q_4(x) = x^2+1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm} | ||

| + | q_5(x) = x^2 + x\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}q_6(x) = x^2+x+1\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| + | |||

| + | * For $m = 4$, besides $q_1(x), \hspace{0.05cm}\text{ ...} \hspace{0.1cm} , \ q_6(x)$ all possible divisor polynomials with degree $m = 3$ must also be considered, thus: | ||

| + | :$$q_i(x) = a_0 + a_1 \cdot x + a_2 \cdot x^2 + x^3\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.5cm}a_0, a_1, a_2 \in \{0,1\} | ||

| + | \hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| + | |||

| + | :For the index, $7 ≤ i ≤ 14 \ \Rightarrow \ N_{\rm D} \ \underline{= 14}$. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | '''(2)''' For the first polynomial holds: $a_1(x = 0) = 0$. Therefore this polynomial is reducible: | ||

| + | :$$a_1(x) = x \cdot (x + 1).$$ | ||

| + | |||

| + | On the other hand, the following is true for the second polynomial: | ||

| + | :$$a_2(x = 0) = 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}a_2(x = 1) = 1 | ||

| + | \hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| + | |||

| + | This necessary but not sufficient property shows that $a_2(x)$ could be irreducible. The final proof is obtained only by two modulo-2 divisions: | ||

| + | * $a_2(x)$ divided by $x$ yields $x + 1$, remainder $r(x) = 1$, | ||

| + | |||

| + | * $a_2(x)$ divided by $x + 1$ yields $x$, remainder $r(x) = 1$. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The correct solution is therefore the <u>proposed solution 2</u>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | '''(3)''' The first three polynomials are reducible, as the following calculation results show: | ||

| + | :$$a_3(x = 0) = 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}a_4(x = 1) = 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}a_5(x = 0) = 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}a_5(x = 1) = 0 | ||

| + | \hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| + | |||

| + | This could have been found out by thinking: | ||

| + | :$$a_3(x) \hspace{-0.15cm} \ = \ \hspace{-0.15cm} x \cdot x \cdot x \hspace{0.05cm},$$ | ||

| + | :$$a_4(x) \hspace{-0.15cm} \ = \ \hspace{-0.15cm} (x^2 + x + 1)\cdot(x + 1) \hspace{0.05cm},$$ | ||

| + | :$$a_5(x) \hspace{-0.15cm} \ = \ \hspace{-0.15cm} x \cdot (x + 1)\cdot(x + 1) \hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| + | |||

| + | The polynomial $a_6(x)$ is not equal to $0$ for both $x = 0$ and $x = 1$ . This means that | ||

| + | * "nothing speaks against" $a_6(x)$ being irreducible, | ||

| + | * division by the irreducible degree-1 polynomials $x$ and $x + 1$, respectively, is not possible without remainder. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | However, since division by the single irreducible degree-2 polynomial also yields a remainder, it is proved that $a_6(x)$ is an irreducible polynomial: | ||

| + | :$$(x^3 + x+1)/(x^2 + x+1) = x + 1 \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.4cm}{\rm Rest}\hspace{0.15cm} r(x) = x\hspace{0.05cm},$$ | ||

| + | |||

| + | Using the same computational procedure, it can also be shown that $a_7(x)$ is also irreducible ⇒ <u>Solutions 4 and 5</u>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | '''(4)''' From $a_8(x + 1) = 0$ follows the reducibility of $a_8(x)$. For the other two polynomials, however, holds: | ||

| + | :$$a_9(x = 0) \hspace{-0.15cm} \ = \ \hspace{-0.15cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.35cm}a_9(x = 1) = 1 \hspace{0.05cm},$$ | ||

| + | :$$a_{10}(x = 0) \hspace{-0.15cm} \ = \ \hspace{-0.15cm}1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}a_{10}(x = 1) = 1 \hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| + | |||

| + | So both could be irreducible. The exact proof of irreducibility is more complicated: | ||

| + | *It is not necessary to use all four divisor polynomials with degree $m = 2$, namely $x^2, \ x^2 + 1, \ x^2 + x + 1$, but it is sufficient to divide by the only irreducible degree-2 polynomial. One obtains with respect to the polynomial $a_9(x)$: | ||

| + | :$$(x^4 + x^3+1)/(x^2 + x+1) = x^2 + 1 \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.4cm}{\rm remainder}\hspace{0.15cm} r(x) = x\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| + | |||

| + | Also the division by the two irreducible degree-3 polynomials yields a remainder in each case: | ||

| + | :$$(x^4 + x^3+1)/(x^3 + x+1) \hspace{-0.15cm} \ = \ \hspace{-0.15cm} x + 1 \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.4cm}{\rm remainder}\hspace{0.15cm} r(x) = x^2\hspace{0.05cm},$$ | ||

| + | :$$(x^4 + x^3+1)/(x^3 + x^2+1) \hspace{-0.15cm} \ = \ \hspace{-0.15cm} x \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.95cm}{\rm remainder}\hspace{0.15cm} r(x) = x +1\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| + | |||

| + | Finally, let us consider the polynomial $a_{10}(x) = x^4 + x^2 + 1$. Here holds | ||

| + | :$$(x^4 + x^2+1)/(x^2 + x+1) = x^2 + x+1 \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.4cm}{\rm remainder}\hspace{0.15cm} r(x) = 0\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| + | |||

| + | It follows: Only the polynomial $a_9(x)$ is irreducible ⇒ <u>proposed solution 2</u>. | ||

{{ML-Fuß}} | {{ML-Fuß}} | ||

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Channel Coding: Exercises|^2.2 Extension Field^]] |

Latest revision as of 17:14, 29 September 2022

Important prerequisites for understanding channel coding are knowledge of polynomial properties.

In this exercise we consider polynomials of the form

- $$a(x) = a_0 + a_1 \cdot x + a_2 \cdot x^2 + \hspace{0.1cm}... \hspace{0.1cm} + a_m \cdot x^{m} \hspace{0.05cm},$$

- where for the coefficients $a_i ∈ {\rm GF}(2) = \{0, \, 1\}$ holds $(0 ≤ i ≤ m)$

- and the highest coefficient is always assumed to $a_m = 1$.

One refers to $m$ as the "degree" of the polynomial.

Adjacent ten polynomials are given where the polynomial degree is either

- $m = 2$ (red font),

- $m = 3$ (blue font) or

- $m = 4$ (green font).

A polynomial $a(x)$ is called reducible if it can be represented as the product of two polynomials $p(x)$ and $q(x)$ of lower degree:

- $$a(x) = p(x) \cdot q(x)$$

If this splitting is not possible, that is, if for the polynomial

- $$a(x) = p(x) \cdot q(x) + r(x)$$

with a residual polynomial $r(x) ≠ 0$ holds, then the polynomial is called irreducible. Such irreducible polynomials are of special importance for the description of error correction methods.

⇒ The proof that a polynomial $a(x)$ of degree $m$ is irreducible requires several polynomial divisions $a(x)/q(x)$, where the degree of the respective divisor polynomial $q(x)$ is always smaller than $m$. Only if all these divisions $($modulo $2)$ always yield a remainder $r(x) ≠ 0$ it is proved that $a(x)$ is indeed an irreducible polynomial.

⇒ This exact proof is very complex. Necessary conditions for $a(x)$ to be an irreducible polynomial at all are the two conditions $($in nonbinary approach "$x=1$" would have to be replaced by "$x≠0$"$)$:

- $a(x = 0) = 1$,

- $a(x = 1) = 1$.

Otherwise, one could write for the polynomial under investigation:

- $$a(x) = q(x) \cdot x \hspace{0.5cm}{\rm resp.}\hspace{0.5cm}a(x) = q(x) \cdot (x+1)\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

The above conditions are necessary, but not sufficient, as the following example shows:

- $$a(x) = x^5 + x^4 +1 \hspace{0.3cm} \Rightarrow\hspace{0.3cm}a(x = 0) = 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}a(x = 1) = 1 \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

Nevertheless, this polynomial is reducible:

- $$a(x) = (x^3 + x +1)(x^2 + x +1) \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

Hint: This exercise belongs to the chapter "Extension field".

Questions

Solution

- with $a_m = 1$

- and given coefficients $a_0, \ a_1, \hspace{0.05cm}\text{ ...} \hspace{0.1cm} , \ a_{m-1}$ $(0$ or $1$ in each case$)$

is irreducible if there is no single polynomial $q(x)$ such that the modulo $2$ division $a(x)/q(x)$ yields no remainder. The degree of all divisor polynomials $q(x)$ to be considered is at least $1$ and at most $m-1$.

- For $m = 2$ two polynomial divisions $a(x)/q_i(x)$ are necessary, namely with

- $$q_1(x) = x \hspace{0.5cm}{\rm and}\hspace{0.5cm}q_2(x) = x+1 \hspace{0.3cm} \Rightarrow\hspace{0.3cm}N_{\rm D}\hspace{0.15cm}\underline{= 2} \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- For $m = 3$ there are already $N_{\rm D} \ \underline{= 6}$ divisor polynomials, namely besides $q_1(x) = x$ and $q_2(x) = x + 1$ also

- $$q_3(x) = x^2\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}q_4(x) = x^2+1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm} q_5(x) = x^2 + x\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}q_6(x) = x^2+x+1\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- For $m = 4$, besides $q_1(x), \hspace{0.05cm}\text{ ...} \hspace{0.1cm} , \ q_6(x)$ all possible divisor polynomials with degree $m = 3$ must also be considered, thus:

- $$q_i(x) = a_0 + a_1 \cdot x + a_2 \cdot x^2 + x^3\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.5cm}a_0, a_1, a_2 \in \{0,1\} \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- For the index, $7 ≤ i ≤ 14 \ \Rightarrow \ N_{\rm D} \ \underline{= 14}$.

(2) For the first polynomial holds: $a_1(x = 0) = 0$. Therefore this polynomial is reducible:

- $$a_1(x) = x \cdot (x + 1).$$

On the other hand, the following is true for the second polynomial:

- $$a_2(x = 0) = 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}a_2(x = 1) = 1 \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

This necessary but not sufficient property shows that $a_2(x)$ could be irreducible. The final proof is obtained only by two modulo-2 divisions:

- $a_2(x)$ divided by $x$ yields $x + 1$, remainder $r(x) = 1$,

- $a_2(x)$ divided by $x + 1$ yields $x$, remainder $r(x) = 1$.

The correct solution is therefore the proposed solution 2.

(3) The first three polynomials are reducible, as the following calculation results show:

- $$a_3(x = 0) = 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}a_4(x = 1) = 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}a_5(x = 0) = 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}a_5(x = 1) = 0 \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

This could have been found out by thinking:

- $$a_3(x) \hspace{-0.15cm} \ = \ \hspace{-0.15cm} x \cdot x \cdot x \hspace{0.05cm},$$

- $$a_4(x) \hspace{-0.15cm} \ = \ \hspace{-0.15cm} (x^2 + x + 1)\cdot(x + 1) \hspace{0.05cm},$$

- $$a_5(x) \hspace{-0.15cm} \ = \ \hspace{-0.15cm} x \cdot (x + 1)\cdot(x + 1) \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

The polynomial $a_6(x)$ is not equal to $0$ for both $x = 0$ and $x = 1$ . This means that

- "nothing speaks against" $a_6(x)$ being irreducible,

- division by the irreducible degree-1 polynomials $x$ and $x + 1$, respectively, is not possible without remainder.

However, since division by the single irreducible degree-2 polynomial also yields a remainder, it is proved that $a_6(x)$ is an irreducible polynomial:

- $$(x^3 + x+1)/(x^2 + x+1) = x + 1 \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.4cm}{\rm Rest}\hspace{0.15cm} r(x) = x\hspace{0.05cm},$$

Using the same computational procedure, it can also be shown that $a_7(x)$ is also irreducible ⇒ Solutions 4 and 5.

(4) From $a_8(x + 1) = 0$ follows the reducibility of $a_8(x)$. For the other two polynomials, however, holds:

- $$a_9(x = 0) \hspace{-0.15cm} \ = \ \hspace{-0.15cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.35cm}a_9(x = 1) = 1 \hspace{0.05cm},$$

- $$a_{10}(x = 0) \hspace{-0.15cm} \ = \ \hspace{-0.15cm}1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}a_{10}(x = 1) = 1 \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

So both could be irreducible. The exact proof of irreducibility is more complicated:

- It is not necessary to use all four divisor polynomials with degree $m = 2$, namely $x^2, \ x^2 + 1, \ x^2 + x + 1$, but it is sufficient to divide by the only irreducible degree-2 polynomial. One obtains with respect to the polynomial $a_9(x)$:

- $$(x^4 + x^3+1)/(x^2 + x+1) = x^2 + 1 \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.4cm}{\rm remainder}\hspace{0.15cm} r(x) = x\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

Also the division by the two irreducible degree-3 polynomials yields a remainder in each case:

- $$(x^4 + x^3+1)/(x^3 + x+1) \hspace{-0.15cm} \ = \ \hspace{-0.15cm} x + 1 \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.4cm}{\rm remainder}\hspace{0.15cm} r(x) = x^2\hspace{0.05cm},$$

- $$(x^4 + x^3+1)/(x^3 + x^2+1) \hspace{-0.15cm} \ = \ \hspace{-0.15cm} x \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.95cm}{\rm remainder}\hspace{0.15cm} r(x) = x +1\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

Finally, let us consider the polynomial $a_{10}(x) = x^4 + x^2 + 1$. Here holds

- $$(x^4 + x^2+1)/(x^2 + x+1) = x^2 + x+1 \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.4cm}{\rm remainder}\hspace{0.15cm} r(x) = 0\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

It follows: Only the polynomial $a_9(x)$ is irreducible ⇒ proposed solution 2.