Contents

- 1 # OVERVIEW OF THE SECOND MAIN CHAPTER #

- 2 Definition of a Galois field

- 3 Examples and properties of Galois fields

- 4 Group, ring, field - basic algebraic concepts

- 5 Definition and examples of an algebraic group

- 6 Definition and examples of an algebraic ring

- 7 Exercises for the chapter

- 8 Quellenverzeichnis

# OVERVIEW OF THE SECOND MAIN CHAPTER #

This chapter discusses the Reed-Solomon codes, invented in the early 1960s by Irving Stoy Reed and Gustave Solomon . Unlike binary block codes, these are based on a Galois field ${\rm GF}(2^m)$ with $m > 1$. So they work with multilevel symbols instead of binary characters (bits).

Specifically, this chapter covers:

- The basics of linear algebra: set, group, ring, field, finite field,

- the definition of extension fields ⇒ ${\rm GF}(2^m)$ and the corresponding operations,

- the meaning of irreducible polynomials and primitive elements,

- the description and realization possibilities of a Reed-Solomon code,

- the error correction of such a code at the binary ersaure channel (BEC),

- the decoding using the Error Locator Polynomial ⇒ Bounded Distance Decoding (BDD),

- the block error probability of Reed-Solomon codes and typical applications.

Definition of a Galois field

Before we can turn to the description of Reed–Solomon codes, we need some basic algebraic notions. We begin with the properties of the Galois field ${\rm GF}(q)$, named after the Frenchman Évariste Galois, whose biography is rather unusual for a mathematician.

$\text{Definition:}$ A $\rm Galois\:field$ ${\rm GF}(q)$ is a finite field with $q$ elements $z_0$, $z_1$, ... , $z_{q-1}$, if the eight statements listed below $\rm (A)$ ... $\rm (H)$ with respect to addition ("$+$") and multiplication ("$\cdot $") are true.

- Addition and multiplication are to be understood here modulo $q$ .

- The $\rm order$ $q$ indicates the number of elements of the Galois field

.

$\text{Criteria of a Galois field:}$

$\rm (A)$ ${\rm GF}(q)$ is closed $\hspace{0.2cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.2cm}\rm Closure$:

- \[\forall \hspace{0.15cm} z_i \in {\rm GF}(q),\hspace{0.15cm} z_j \in {\rm GF}(q)\text{:} \hspace{0.25cm}(z_i + z_j)\in {\rm GF}(q),\hspace{0.15cm}(z_i \cdot z_j)\in {\rm GF}(q) \hspace{0.05cm}. \]

$\rm (B)$ There is a neutral element $N_{\rm A}$ with respect to addition, the so-called zero element. $\hspace{0.2cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.2cm}\rm Identity \ for \ "\hspace{-0.05cm}+\hspace{0.05cm}"$:

- \[\exists \hspace{0.15cm} z_j \in {\rm GF}(q)\text{:} \hspace{0.25cm}z_i + z_j = z_i \hspace{0.25cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.25cm} z_j = N_{\rm A} = \text{ 0} \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

$\rm (C)$ There is a neutral element $N_{\rm M}$ with respect to multiplication, the so-called identity element $\hspace{0.2cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.2cm}\rm Identity \ for \ "\hspace{-0.05cm}·\hspace{0.05cm}"$:

- \[\exists \hspace{0.15cm} z_j \in {\rm GF}(q)\text{:} \hspace{0.25cm}z_i \cdot z_j = z_i \hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} z_j = N_{\rm M} = {1} \hspace{0.05cm}. \]

$\rm (D)$ For each $z_i$ there exists an additive inverse ${\rm Inv_A}(z_i)$ $\hspace{0.2cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.2cm}\rm Inverse \ for \ "\hspace{-0.05cm}+\hspace{0.05cm}"$:

- \[\forall \hspace{0.15cm} z_i \in {\rm GF}(q),\hspace{0.15cm} \exists \hspace{0.15cm} {\rm Inv_A}(z_i) \in {\rm GF}(q)\text{:} \hspace{0.25cm}z_i + {\rm Inv_A}(z_i) = N_{\rm A} = {0} \hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}\text{kurz:}\hspace{0.3cm} {\rm Inv_A}(z_i) = - z_i \hspace{0.05cm}. \]

$\rm (E)$ For each $z_i$ except the zero element, there exists the multiplicative inverse ${\rm Inv_M}(z_i)$ $\hspace{0.2cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.2cm}\rm Inverse \ for \ "\hspace{-0.05cm}\cdot\hspace{0.05cm}"$:

- \[\forall \hspace{0.15cm} z_i \in {\rm GF}(q),\hspace{0.15cm} z_i \ne N_{\rm A}, \hspace{0.15cm} \exists \hspace{0.15cm} {\rm Inv_M}(z_i) \in {\rm GF}(q)\text{:} \hspace{0.25cm}z_i \cdot {\rm Inv_M}(z_i) = N_{\rm M} = {1}\hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}\text{kurz:}\hspace{0.3cm} {\rm Inv_M}(z_i) = z_i^{-1} \hspace{0.05cm}. \]

$\rm (F)$ For addition and multiplication the commutative law applies in each case $\hspace{0.2cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.2cm}\rm Commutative \ Law$:

- \[\forall \hspace{0.15cm} z_i,\hspace{0.15cm} z_j \in {\rm GF}(q)\text{:} \hspace{0.25cm}z_i + z_j = z_j + z_i ,\hspace{0.15cm}z_i \cdot z_j = z_j \cdot z_i \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

$\rm (G)$ For addition and multiplication, the associative law applies in each case $\hspace{0.2cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.2cm}\rm Associative \ Law$:

- \[\forall \hspace{0.15cm} z_i,\hspace{0.1cm} z_j ,\hspace{0.1cm} z_k \in {\rm GF}(q)\text{:} \hspace{0.25cm}(z_i + z_j) + z_k = z_i + (z_j + z_k ),\hspace{0.15cm}(z_i \cdot z_j) \cdot z_k = z_i \cdot (z_j \cdot z_k ) \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

$\rm (H)$ For the combination "addition – multiplication" the distributive law is valid $\hspace{0.2cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.2cm}\rm Distributive \ Law$:

- \[\forall \hspace{0.15cm} z_i,\hspace{0.15cm} z_j ,\hspace{0.15cm} z_k \in {\rm GF}(q)\text{:} \hspace{0.25cm}(z_i + z_j) \cdot z_k = z_i \cdot z_k + z_j \cdot z_k \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

Examples and properties of Galois fields

We first check that for the binary number set $Z_2 = \{0, 1\}$ ⇒ $q=2$ (valid for the simple binary code) the eight criteria mentioned on the last page are met, so that we can indeed speak of "${\rm GF}(2)$". You can see the addition– and multiplication table below:

- $$Z_2 = \{0, 1\}\hspace{0.25cm} \Rightarrow\hspace{0.25cm}\text{Addition: } \left[ \begin{array}{c|cccccc} + & 0 & 1 \\ \hline 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 1 & 0 \end{array} \right] \hspace{-0.1cm} ,\hspace{0.25cm}\text{Multiplication: } \left[ \begin{array}{c|cccccc} \cdot & 0 & 1 \\ \hline 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 1 \end{array} \right]\hspace{0.25cm} \Rightarrow\hspace{0.25cm}{\rm GF}(2) . $$

One can see from this representation:

- Each element of the addition– and multiplication table of $Z_2$ is again $z_0 = 0$ or $z_0 = 1$ ⇒ the criterion $\rm (A)$ is satisfied.

- The set $Z_2$ contains the zero element $(\hspace{-0.05cm}N_{\rm A} = z_0 = 0)$ and the one element $(\hspace{-0.05cm}N_{\rm M} = z_1 = 1)$ ⇒ the criteria $\rm (B)$ and $\rm (C)$ are satisfied.

- The additive inverses ${\rm Inv_A}(0) = 0$ and ${\rm Inv_A}(1) = -1$ exist and belong to $Z_2$.

- Similarly, the multiplicative inverse ${\rm Inv_M}(1) = 1$ ⇒ criteria $\rm (D)$ and $\rm (E)$ are satisfied.

- The validity of the commutative law $\rm (F)$ in the set $Z_2$ can be recognized by the symmetry with respect to the table diagonals.

- The criteria $\rm (G)$ and $\rm (H)$ are also satisfied here ⇒ all eight criteria are satisfied ⇒ $Z_2 = \rm GF(2)$.

$\text{Example 1:}$ The set of numbers $Z_3 = \{0, 1, 2\}$ ⇒ $q = 3$ satisfies all eight criteria and is thus a Galois field $\rm GF(3)$:

- $$Z_3 = \{0, 1, 2\}\hspace{0.25cm} \Rightarrow\hspace{0.25cm}\text{Addition: } \left[ \begin{array}{c | cccccc} + & 0 & 1 & 2\\ \hline 0 & 0 & 1 & 2 \\ 1 & 1 & 2 & 0 \\ 2 & 2 & 0 & 1 \end{array} \right] \hspace{-0.1cm} ,\hspace{0.25cm}\text{Multiplication: } \left[ \begin{array}{c | cccccc} \cdot & 0 & 1 & 2\\ \hline 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 1 & 2 \\ 2& 0 & 2 & 1 \end{array} \right]\hspace{0.25cm} \Rightarrow\hspace{0.25cm}{\rm GF}(3) . $$

$\text{Example 2:}$ In contrast, the set of numbers $Z_4 = \{0, 1, 2, 3\}$ ⇒ $q = 4$ is not a Galois field.

- The reason for this is that there is no multiplicative inverse to the element $z_2 = 2$ here. For a Galois field it would have to be true: $2 \cdot {\rm Inv_M}(2) = 1$.

- But in the multiplication table there is no entry with "$1$" in the third row and third column $($each valid for the multiplicand $z_2 = 2)$ .

- $$Z_4 = \{0, 1, 2, 3\}\hspace{0.25cm} \Rightarrow\hspace{0.25cm}\text{Addition: } \left[ \begin{array}{c | cccccc} + & 0 & 1 & 2 & 3\\ \hline 0 & 0 & 1 & 2 & 3\\ 1 & 1 & 2 & 3 & 0\\ 2 & 2 & 3 & 0 & 1\\ 3 & 3 & 0 & 1 & 2 \end{array} \right] \hspace{-0.1cm} ,\hspace{0.25cm}\text{Multiplication: } \left[ \begin{array}{c | cccccc} \cdot& 0 & 1 & 2 & 3\\ \hline 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0\\ 1 & 0 & 1 & 2 & 3\\ 2 & 0 & 2 & 0 & 2\\ 3 & 0 & 3 & 2 & 1 \end{array} \right]\hspace{0.25cm} \Rightarrow\hspace{0.25cm}\text{kein }{\rm GF}(4) . $$

$\text{Generalization (without proof for now):}$

- A Galois field ${\rm GF}(q)$ can be formed in the manner described here as "Ring" of integer sizes modulo $q$ only if $q$ is a prime number:

$q = 2$, $q = 3$, $q = 5$, $q = 7$, $q = 11$, ...

- But if the order $q$ can be expressed in the form $q = P^m$ with a prime $P$ and integer $m$ , the Galois field ${\rm GF}(q)$ can be found via a extension fields find.

Group, ring, field - basic algebraic concepts

On the first pages, some basic algebraic terms have already been mentioned, without their meanings having been explained in more detail. This is to be made up now in all shortness from view of a communication engineer, whereby we mainly refer to the representation in [Fri96]. [Fri96][1] und [KM+08][2] . To summarize:

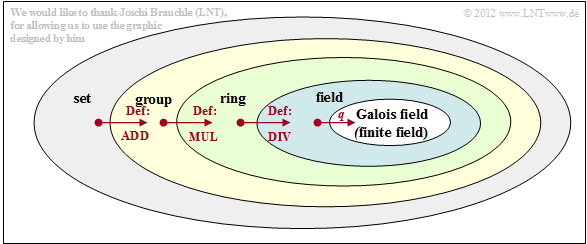

$\text{Definition:}$ A $\rm Galois field$ ${\rm GF}(q)$ is a field with a finite number $(q)$ of elements ⇒ finite field. Each field is again a special case of a ring, which itself can be represented again as a special case of an abelian group.

The diagram illustrates step by step how the following subordinate sets arise from a set by definition of addition, multiplication and division within this set $\mathcal{M}$ :

- abelian group $\mathcal{G}$ ,

- ring $\mathcal{R}$,

- field $\mathcal{F}$,

- finite field $\mathcal{F}_q$ or Galois field ${\rm GF}(q)$.

On the next two pages, the algebraic terms mentioned here will be discussed in more detail.

- For understanding the Reed–Solomon codes, however, this knowledge is not absolutely necessary.

- So you could jump directly to the chapter extension fields .

Definition and examples of an algebraic group

For the general definitions of group (and later ring) we assume a set with infinitely many elements:

- \[\mathcal{M} = \{\hspace{0.1cm}z_1,\hspace{0.1cm} z_2,\hspace{0.1cm} z_3 ,\hspace{0.1cm}\text{ ...} \hspace{0.1cm}\}\hspace{0.05cm}. \]

$\text{Definition:}$ A $\text{algebraic group}$ $(\mathcal{G}, +)$ is an (arbitrary) subset $\mathcal{G} ⊂ \mathcal{M}$ together with an additive linkage ("$+$") defined between all elements, but only if the following properties are necessarily satisfied:

- For all $z_i, z_j ∈ \mathcal{G}$ holds $(z_i + z_j) ∈ \mathcal{G}$ ⇒ Closure–criterion for "$+$".

- There is always an element neutral with respect to addition $N_{\rm A} ∈ \mathcal{G}$, so that for all $z_i ∈ \mathcal{G}$ holds: $z_i +N_{\rm A} = z_i$. Given a group of numbers, $N_{\rm A} \equiv 0$.

- For all $z_i ∈ \mathcal{G}$ there is also an element inverse with respect to addition ${\rm Inv_A}(z_i) ∈ \mathcal{G}$ with property $z_i + {\rm Inv_A}(z_i)= N_{\rm A} $.

For a group of numbers ${\rm Inv_A}(z_i) =- z_i$.

- For all $z_i, z_j, z_k ∈ \mathcal{G}$ holds: $z_i + (z_j + z_k)= (z_i + z_j) + z_k$ ⇒ Associative law for "$+$".

If in addition for all $z_i, z_j ∈ \mathcal{G}$ the commutative law $z_i + z_j= z_j + z_i$ is satisfied, one speaks of a commutative group or an abelian group, named after the Norwegian mathematician Niels Hendrik Abel.

$\text{Examples of algebraic groups:}$

(1) The set of rational numbers is defined as the set of all quotients $I/J$ with integers $I$ and $J ≠ 0$.

- This set is a group $(\mathcal{G}, +)$ with respect to addition, since

- for all $a ∈ \mathcal{G}$ and $b ∈ \mathcal{G}$ also the sum $a+b$ belongs again to $\mathcal{G}$ ,

- the associative law applies,

- with $ N_{\rm A} = 0$ the neutral element of the addition is contained in $\mathcal{G}$ and

- it exists for each $a$ the additive inverse ${\rm Inv_A}(a) = -a$ .

- for all $a ∈ \mathcal{G}$ and $b ∈ \mathcal{G}$ also the sum $a+b$ belongs again to $\mathcal{G}$ ,

- Since moreover the commutative law is fulfilled, it is an abelian group.

(2) The set of natural numbers ⇒ $\{0, 1, 2, \text{...}\}$ is not an algebraic group with respect to addition,

- since for no single element $z_i$ there exists the additive inverse ${\rm Inv_A}(z_i) = -z_i$ .

- since for no single element $z_i$ there exists the additive inverse ${\rm Inv_A}(z_i) = -z_i$ .

(3) The bounded set of natural numbers ⇒ $\{0, 1, 2, \text{...}\hspace{0.05cm}, q-1\}$ on the other hand then satisfies the conditions on a group $(\mathcal{G}, +)$,

- if one defines the addition modulo $q$ .

(4) On the other hand, $\{1, 2, 3, \text{...}\hspace{0.05cm},q\}$ is not a group because the neutral element of addition $(N_{\rm A} = 0)$ is missing.

Definition and examples of an algebraic ring

According to the overview graphic one gets from the group $(\mathcal{G}, +)$ by defining a second arithmetic operation – of multiplication ("$\cdot$") – to the ring $(\mathcal{R}, +, \cdot)$. So you need a multiplication table as well as an addition table for this.

$\text{Definition:}$ A $\text{algebraic ring}$ $(\mathcal{R}, +, \cdot)$ is a subset $\mathcal{R} ⊂ \mathcal{G} ⊂ \mathcal{M}$ together with two arithmetic operations defined in this set, addition ("$+$") and multiplication ("$·$"). The following properties must be satisfied:

- In terms of addition, the ring $(\mathcal{R}, +, \cdot)$ is an abelian group $(\mathcal{G}, +)$.

- In addition, for all $z_i, z_j ∈ \mathcal{R}$ also $(z_i \cdot z_j) ∈ \mathcal{R}$ ⇒ Closure–criterion for "$\cdot$".

- There is always also an element neutral with respect to multiplication $N_{\rm M} ∈ \mathcal{R}$, so that for all $z_i ∈ \mathcal{R}$ holds: $z_i \cdot N_{\rm M} = z_i$.

For a number group is always $N_{\rm M} = 1$.

- For all $z_i, z_j, z_k ∈ \mathcal{R}$ holds: $z_i + (z_j + z_k)= (z_i + z_j) + z_k$ ⇒ Associative law for "$\cdot $".

- For all $z_i, z_j, z_k ∈ \mathcal{R}$ holds: $z_i \cdot (z_j + z_k) = z_i \cdot z_j + z_i \cdot z_k$ ⇒ Distributive law for "$\cdot $".

Further the following agreements shall hold:

- A ring $(\mathcal{R}, +, \cdot)$ is not necessarily commutative. If in fact the commutative law also holds for all elements $z_i, z_j ∈ \mathcal{R}$ with respect to multiplication, $z_i \cdot z_j= z_j \cdot z_i$ is called a commutative ring in the technical literature.

- Exists for each element $z_i ∈ \mathcal{R}$ except $N_{\rm A}$ (neutral element of addition, zero element) an element inverse with respect to multiplication ${\rm Inv_M}(z_i)$ such that $z_i \cdot {\rm Inv_M}(z_i) = 1$ holds, then there is a division ring .

- The ring is free of zero divisors if from $z_i \cdot z_j = 0$ follows necessarily $z_i = 0$ or $z_j = 0$ . In abstract algebra, a zero divisor of a ring is an element $z_i$ different from the zero element if there exists an element $z_j \ne 0$ such that the product $z_i \cdot z_j = 0$ .

- A commutative ring free of zero divisors is called integral domain.

$\text{Conclusion:}$

Comparing the definitions of Group, Ring (see above), Body and Galois field, we recognize that a Galois field ${\rm GF}(q)$

- is a finite field with $q$ elements,

- at the same time as a commutative division ring and also

- describes an integral domain

Exercises for the chapter

Aufgabe 2.1: Gruppe, Ring, Körper

Aufgabe 2.1Z: Welche Tabellen beschreiben Gruppen?

Aufgabe 2.2: Eigenschaften von Galoisfeldern

Aufgabe 2.2Z: Galoisfeld GF(5)

Quellenverzeichnis