Direct Current Signal - Limit Case of a Periodic Signal

Contents

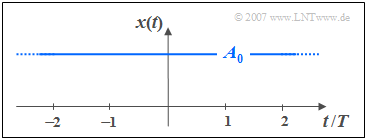

Time signal representation

$\text{Definition:}$ A »direct current (DC) signal« is a deterministic signal whose instantaneous values are constant for all times $t$ from $-\infty$ to $+\infty$. Such a signal is the borderline case of a »harmonic oscillation«, where the period duration $T_{0}$ has an infinitely large value.

According to this definition a DC signal always ranges from $t = -\infty$ to $t = +\infty$. If the constant signal is only switched on at the time $t = 0$ there is no DC signal.

- A direct signal can never be a carrier of information in a communication system,  but transmitted signals can possess a »direct signal component«.

- All statements made in the following for the direct current signal apply in the same way also to such a direct signal component.

$\text{Definition:}$ For the »DC signal component« $A_{0}$ of any signal $x(t)$ applies:

- $$A_0 = \lim_{T_{\rm M}\to\infty}\,\frac{1}{T_{\rm M} }\cdot\int^{T_{\rm M}/2}_{-T_{\rm M}/2}x(t)\,{\rm d} t. $$

- The measurement duration $T_{\rm M}$ should always be selected as large as possible $($infinite in borderline cases$)$.

- The given equation is only valid if $T_{\rm M}$ lies symmetrical about the time $t=0$.

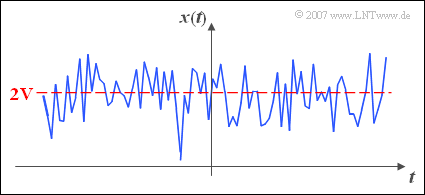

$\text{Example 1:}$ The graph shows a random signal $x(t)$.

- The DC component is here $A_{0} = 2\ \rm V$.

- In the sense of statistics, $A_{0}$ corresponds to the linear mean.

Spectral representation

We now look at the situation in the frequency domain. From the time function it is already obvious, that it contains – spectrally speaking – only one single $($physical$)$ frequency, namely the frequency $f=0$.

⇒ This result shall now be derived mathematically. In anticipation of the chapter »Fourier Transform« the connection between the time signal $x(t)$ and the corresponding spectrum $X(f)$ is already given here:

- $$X(f)= \hspace{0.05cm}\int_{-\infty} ^{{+}\infty} x(t) \, \cdot \, { \rm e}^{-\rm j 2\pi \it ft} \,{\rm d}t.$$

The spectral function $X(f)$ is called after the French mathematician $\text{Jean Baptiste Joseph Fourier}$ the »Fourier transform« of the signal $x(t)$ and the short labeling for this functional relation is

- $$X(f)\ \bullet\!\!-\!\!\!-\!\!\circ\,\ x(t).$$

For example, if $x(t)$ describes a voltage curve, so $X(f)$ has the unit "V/Hz".

⇒ Applying the Fourier transform to the DC signal $x(t)=A_{0}$ yields the spectral function

- $$X(f)= A_0 \cdot \int_{-\infty} ^{+\hspace{0.01cm}\infty}\rm e \it ^{-\rm {j 2\pi} \it ft} \,{\rm d}t$$

with the following properties:

- The integral diverges for $f=0$, i.e. it returns an infinitely large value $($integration over the constant value $1)$.

- For a frequency $f\ne 0$, on the other hand, the integral is zero; the corresponding proof, however, is not trivial $($see next section$)$.

$\text{Definition:}$ The searched spectral function $X(f)$ is compactly expressed by the following equation:

- $$X(f) = A_0 \, \cdot \, \rm \delta(\it f).$$

- $\delta(f)$ is denoted as the »Dirac delta function«, also known as »distribution«.

- $\delta(f)$ is a mathematically complicated function; the derivation can be found in the next section.

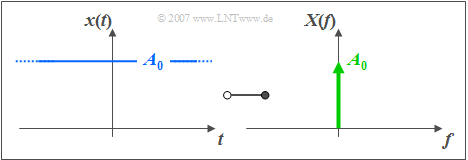

$\text{Example 2:}$ The graphic shows the functional connection

- between an DC signal $x(t)=A_{0}$ and

- its corresponding spectral function $X(f)=A_{0} \cdot \delta(f)$.

The Dirac delta function at frequency $f=0$ is represented by an arrow with weight $A_{0}$.

Dirac (delta) function in frequency domain

$\text{Definition:}$ The »Dirac delta function« ⇒ short: »Dirac function« has the following properties:

- The Dirac delta function is infinitely narrow, i.e. it is $\delta(f)=0$ for $f \neq 0$.

- The Dirac delta function $\delta(f)$ is infinitely high at the frequency $f = 0$ .

- The Dirac delta weight $($area of the Dirac function$)$ yields a finite value, namely $1$:

- $$\int_\limits{-\infty} ^{+\infty} \delta( f)\,{\rm d}f =1.$$

- It follows from this last property that $\delta(f)$ has the unit ${\rm Hz}^{-1} = {\rm s}$ .

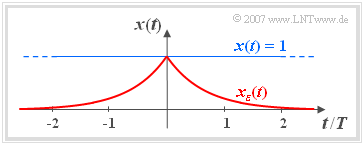

$\text{Proof:}$ For the mathematical derivation of these properties we assume a dimensionless DC signal $x(t)$.

- To force the convergence of the Fourier integral, the non-energy-limited signal $x(t)$ is multiplied by a bilateral declining exponential function.

- The graph shows the signal $x(t)=1$ and the energy-limited signal

- $$x_{\varepsilon} (t) = \rm e^{\it -\varepsilon \hspace{0.05cm} \cdot \hspace{0.05cm} \vert \hspace{0.01cm} t \hspace{0.01cm}\vert}{.}$$

- It applies $\varepsilon > 0$. At the limit $\varepsilon \to 0$ , $x_{\varepsilon}(t)$ passes to $x(t)=1$.

- The spectral representation is obtained by applying the Fourier integral given above:

- $$X_\varepsilon (f)=\int_{-\infty}^{0} {\rm e}^{\varepsilon{t} }\, {\cdot}\, {\rm e}^{-\rm j 2\pi \it ft} \,{\rm d}t \hspace{0.2cm}+ \hspace{0.2cm} \int_{0}^{+\infty} {\rm e}^{-\varepsilon t} \,{\cdot}\, { \rm e}^{-\rm j 2\pi \it ft} \,{\rm d}t.$$

- After integration and combination of both parts we obtain the purely real spectral function of the energy-limited signal $x_{\varepsilon}(t)$:

- $$X_\varepsilon (f)=\frac{1}{\varepsilon -\rm j \cdot 2\pi \it f} + \frac{1}{\varepsilon+\rm j \cdot 2\pi \it f} = \frac{2\varepsilon}{\varepsilon^2 + (\rm 2\pi {\it f}\hspace{0.05cm} ) \rm ^2} \, .$$

- The area under the $X_\varepsilon (f)$ curve is independent of the parameter $\varepsilon$ equals $1$. The smaller $ε$ is selected, the narrower and higher the function becomes, as the $($German language$)$ learning video »Herleitung und Visualisierung der Diracfunktion« ⇒ "Derivation and visualization of the Dirac delta function" shows.

- The limit for $\varepsilon \to 0$ returns the Dirac delta function with weight $1$:

- $$\lim_{\varepsilon \hspace{0.05cm} \to \hspace{0.05cm} 0}X_\varepsilon (f)= \delta(f).$$

Exercises for the chapter

Exercise 2.2: Direct Current Component of Signals

Exercise 2.2Z: Non–Linearities