Difference between revisions of "Theory of Stochastic Signals/Probability Density Function"

(Die Seite wurde neu angelegt: „ {{Header |Untermenü=Kontinuierliche Zufallsgrößen |Vorherige Seite=Erzeugung von diskreten Zufallsgrößen |Nächste Seite=Verteilungsfunktion (VTF) }} ==…“) |

|||

| (47 intermediate revisions by 9 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | |||

{{Header | {{Header | ||

| − | |Untermenü= | + | |Untermenü=Continuous Random Variables |

| − | |Vorherige Seite= | + | |Vorherige Seite=Generation of Discrete Random Variables |

| − | |Nächste Seite= | + | |Nächste Seite=Cumulative Distribution Function |

}} | }} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | In | + | == # OVERVIEW OF THE THIRD MAIN CHAPTER # == |

| + | <br> | ||

| + | We consider here »'''continuous random variables'''«, i.e., random variables which can assume infinitely many different values, at least in certain ranges of real numbers. | ||

| + | *Their applications in information and communication technology are manifold. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *They are used, among other things, for the simulation of noise signals and for the description of fading effects. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | We restrict ourselves at first to the statistical description of the »'''amplitude distribution'''«. In detail, the following are treated: | ||

| + | |||

| + | *The relationship between »probability density function« $\rm (PDF)$ and »cumulative distribution function« $\rm (CDF)$; | ||

| + | *the calculation of »expected values and moments«; | ||

| + | *some »special cases« of continuous-value distributions: | ||

| + | #uniform distributed random variables, | ||

| + | #Gaussian distributed random variables, | ||

| + | #exponential distributed random variables, | ||

| + | #Laplace distributed random variables, | ||

| + | #Rayleigh distributed random variables, | ||

| + | #Rice distributed random variables, | ||

| + | #Cauchy distributed random variables; | ||

| + | *the »generation of continuous random variables« on a computer. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | »'''Inner statistical dependencies'''« of the underlying processes '''are not considered here'''. For this, we refer to the following main chapters $4$ and $5$. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==Properties of continuous random variables== | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | In the second chapter it was shown that the amplitude distribution of a discrete random variable is completely determined by its $M$ occurrence probabilities, where the level number $M$ usually has a finite value. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{BlaueBox|TEXT= | ||

| + | $\text{Definition:}$ By a »'''value-continuous random variable'''« is meant a random variable whose possible numerical values are uncountable ⇒ $M \to \infty$. In the following, we will often use the short form »continuous random variable«.}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Further it shall hold: | ||

| + | #We (mostly) denote value-continuous random variables with $x$ in contrast to the value-discrete random variables, which are denoted with $z$ as before. | ||

| + | #No statement is made here about a possible time discretization, i.e., value-continuous random variables can be discrete in time. | ||

| + | #We assume for this chapter that there are no statistical bindings between the individual samples $x_ν$, or at least leave them out of consideration. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | {{GraueBox|TEXT= | ||

| + | $\text{Example 1:}$ | ||

| + | The graphic shows a section of a stochastic noise signal $x(t)$ whose instantaneous value can be taken as a continuous random variable $x$. | ||

| + | [[File: P_ID41__Sto_T_3_1_S1_neu.png |right|frame| Signal and PDF of a Gaussian noise signal]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | *From the »probability density function» $\rm (PDF)$ shown on the right, it can be seen that instantaneous values around the mean $m_1$ occur most frequently for any exemplary signal. | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Since there are no statistical dependencies between the samples $x_ν$, such a signal is often also referred to as »'''white noise'''«.}} | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Definition of the probability density function== | |

| − | {{ | + | <br> |

| − | + | For a value-continuous random variable, the probabilities that it takes on quite specific values are zero. Therefore, to describe a value-continuous random variable, we must always refer to the »probability density function« $\rm (PDF)$. | |

| − | == | + | |

| − | + | {{BlaueBox|TEXT= | |

| + | $\text{Definition:}$ | ||

| + | The value of the »'''probability density function'''« $f_{x}(x)$ at location $x_\mu$ is equal to the probability that the instantaneous value of the random variable $x$ lies in an $($infinitesimally small$)$ interval of width $Δx$ around $x_\mu$, divided by $Δx$: | ||

| + | :$$f_x(x=x_\mu) = \lim_{\rm \Delta \it x \hspace{0.05cm}\to \hspace{0.05cm}\rm 0}\frac{\rm Pr \{\it x_\mu-\rm \Delta \it x/\rm 2 \le \it x \le x_\mu \rm +\rm \Delta \it x/\rm 2\} }{\rm \Delta \it x}.$$}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | This extremely important descriptive variable has the following properties: | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Although from the time course in [[Theory_of_Stochastic_Signals/Probability_Density_Function_(PDF)#Properties_of_continuous_random_variables|$\text{Example 1}$]] it can be seen that the most frequent signal components lie at $x = m_1$ and the PDF has its largest value here, for a value-continuous random variable the probability ${\rm Pr}(x = m_1)$, that the instantaneous value is exactly equal to the mean $m_1$, is identically zero. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *The probability that the random variable lies in the range between $x_{\rm u}$ and $x_{\rm o}$: | ||

| + | :$${\rm Pr}(x_{\rm u} \le x \le x_{\rm o})= \int_{x_{\rm u} }^{x_{\rm o} }f_{x}(x) \,{\rm d}x.$$ | ||

| + | |||

| + | *As an important normalization property, this yields for the area under the PDF with the boundary transitions $x_{\rm u} → \hspace{0.05cm} - \hspace{0.05cm} ∞$ and $x_{\rm o} → +∞:$ | ||

| + | :$$\int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} f_{x}(x) \,{\rm d}x = \rm 1.$$ | ||

| + | |||

| + | *The corresponding equation for value-discrete, $M$-level random variables states that the sum over the $M$ occurrence probabilities gives the value $1$. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | {{BlaueBox|TEXT= | ||

| + | $\text{Note on nomenclature:}$ | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the literature, a distinction is often made between the random variable $X$ and its realizations $x ∈ X$. Thus, the above definition equation is | ||

| + | :$$f_{X}(X=x) = \lim_{ {\rm \Delta} x \hspace{0.05cm}\to \hspace{0.05cm} 0}\frac{ {\rm Pr} \{ x - {\rm \Delta} x/2 \le X \le x +{\rm \Delta} x/ 2\} }{ {\rm \Delta} x}.$$ | ||

| + | |||

| + | We have largely dispensed with this more precise nomenclature in our $\rm LNTwww$ so as not to use up two letters for one quantity. | ||

| + | #Lowercase letters $($as $x)$ often denote signals and uppercase letters $($as $X)$ the associated spectra in our case. | ||

| + | #Nevertheless, today (2017) we have to honestly admit that the 2001 decision was not entirely happy.}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==PDF definition for discrete random variables== | ||

| + | For reasons of a uniform representation of all random variables $($both value-discrete and value-continuous$)$, it is convenient to define the probability density function also for value-discrete random variables. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{BlaueBox|TEXT= | ||

| + | $\text{Definition:}$ | ||

| + | Applying the definition equation of the last section to value-discrete random variables, the PDF takes infinitely large values at some points $x_\mu$ due to the nonvanishingly small probability value and the limit transition $Δx → 0$. | ||

| − | + | Thus, the PDF results in a sum of [[Signal_Representation/Direct_Current_Signal_-_Limit_Case_of_a_Periodic_Signal#Dirac_.28delta.29_function_in_frequency_domain|»Dirac delta functions«]] ⇒ »distributions«: | |

| − | + | :$$f_{x}(x)=\sum_{\mu=1}^{M}p_\mu\cdot {\rm \delta}( x-x_\mu).$$ | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | The weights of these Dirac delta functions are equal to the probabilities $p_\mu = {\rm Pr}(x = x_\mu$).}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | Here is another note to help classify the different descriptive quantities for value-discrete and value-continuous random variables: Probability and probability density function are related in a similar way as in the book [[Signal_Representation|»Signal Representation«]] | ||

| + | *a discrete spectral component of a harmonic oscillation ⇒ line spectrum, and | ||

| + | |||

| + | *a continuous spectrum of an energy-limited $($pulse-shaped$)$ signal. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | {{GraueBox|TEXT= | ||

| + | [[File:P_ID40__Sto_T_3_1_S3_NEU.png|right|frame|Signal and PDF of a ternary signal]] | ||

| + | $\text{Example 2:}$ Below you can see a section | ||

| + | |||

| + | *of a rectangular signal with three possible values, | ||

| − | + | *where the signal value $0 \ \rm V$ occurs twice as often as the outer signal values $(\pm 1 \ \rm V)$. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Thus, the corresponding PDF $($values from top to bottom$)$: | |

| − | + | :$$f_{x}(x) = 0.25 \cdot \delta(x - {\rm 1 V})+ 0.5\cdot \delta(x) + 0.25\cdot \delta (x + 1\rm V).$$ | |

| − | |||

| + | ⇒ For a more in-depth look at the topic covered here, we recommend the following $($German language$)$ learning video: | ||

| − | + | :[[Wahrscheinlichkeit_und_WDF_(Lernvideo)|»Wahrscheinlichkeit und WDF«]] ⇒ »Probability and probability density function«}} | |

| − | |||

| − | [[File: | + | ==Numerical determination of the PDF== |

| + | <br> | ||

| + | You can see here a scheme for the numerical determination of the probability density function. Assuming that the random variable $x$ at hand has negligible values outside the range from $x_{\rm min} = -4.02$ to $x_{\rm max} = +4.02$, proceed as follows: | ||

| + | [[File:EN_Sto_T_3_1_S4_neu.png |right|frame| For numerical determination of the PDF]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | #Divide the range of $x$-values into $I$ intervals of equal width $Δx$ and define a field PDF$[0 : I-1]$. In the sketch $I = 201$ and accordingly $Δx = 0.04$ is chosen. | ||

| + | #The random variable $x$ is now called $N$ times in succession, each time checking to which interval $i_{\rm act}$ the current random variable $x_{\rm act}$ belongs: <br> $i_{\rm act} = ({\rm int})((x + x_{\rm max})/Δx).$ | ||

| + | #The corresponding field element PDF( $i_{\rm act}$) is then incremented by $1$. | ||

| + | #After $N$ iterations, PDF$[i_{\rm act}]$ then contains the number of random numbers belonging to the interval $i_{\rm act}$. | ||

| + | #The actual PDF values are obtained if, at the end, all field elements PDF$[i]$ with $0 ≤ i ≤ I-1$ are still divided by $N \cdot Δx$. | ||

| + | <br clear=all> | ||

| + | {{GraueBox|TEXT= | ||

| + | $\text{Example 3:}$ | ||

| + | From the drawn green arrows in the graph above, one can see: | ||

| + | *The value $x_{\rm act} = 0.07$ leads to the result $i_{\rm act} =$ (int) ((0.07 + 4.02)/0.04) = (int) $102.25$. | ||

| + | * Here »(int)« means an integer conversion after float division ⇒ $i_{\rm act} = 102$. | ||

| + | *The same interval $i_{\rm act} = 102$ results for $0.06 < x_{\rm act} < 0.10$, so for example also for $x_{\rm act} = 0.09$. }} | ||

| − | + | ==Exercises for the chapter== | |

| − | + | <br> | |

| + | [[Aufgaben:Exercise_3.1:_cos²-PDF_and_PDF_with_Dirac_Functions|Exercise 3.1: Cosine-square PDF and PDF with Dirac Functions]] | ||

| + | [[Aufgaben:Exercise_3.1Z:_Triangular_PDF|Exercise 3.1Z: Triangular PDF]] | ||

{{Display}} | {{Display}} | ||

Latest revision as of 17:26, 14 February 2024

Contents

# OVERVIEW OF THE THIRD MAIN CHAPTER #

We consider here »continuous random variables«, i.e., random variables which can assume infinitely many different values, at least in certain ranges of real numbers.

- Their applications in information and communication technology are manifold.

- They are used, among other things, for the simulation of noise signals and for the description of fading effects.

We restrict ourselves at first to the statistical description of the »amplitude distribution«. In detail, the following are treated:

- The relationship between »probability density function« $\rm (PDF)$ and »cumulative distribution function« $\rm (CDF)$;

- the calculation of »expected values and moments«;

- some »special cases« of continuous-value distributions:

- uniform distributed random variables,

- Gaussian distributed random variables,

- exponential distributed random variables,

- Laplace distributed random variables,

- Rayleigh distributed random variables,

- Rice distributed random variables,

- Cauchy distributed random variables;

- the »generation of continuous random variables« on a computer.

»Inner statistical dependencies« of the underlying processes are not considered here. For this, we refer to the following main chapters $4$ and $5$.

Properties of continuous random variables

In the second chapter it was shown that the amplitude distribution of a discrete random variable is completely determined by its $M$ occurrence probabilities, where the level number $M$ usually has a finite value.

$\text{Definition:}$ By a »value-continuous random variable« is meant a random variable whose possible numerical values are uncountable ⇒ $M \to \infty$. In the following, we will often use the short form »continuous random variable«.

Further it shall hold:

- We (mostly) denote value-continuous random variables with $x$ in contrast to the value-discrete random variables, which are denoted with $z$ as before.

- No statement is made here about a possible time discretization, i.e., value-continuous random variables can be discrete in time.

- We assume for this chapter that there are no statistical bindings between the individual samples $x_ν$, or at least leave them out of consideration.

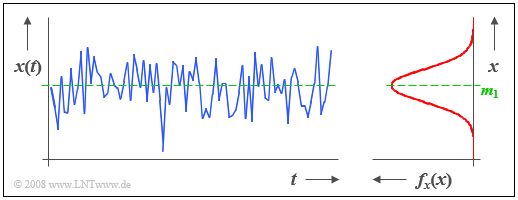

$\text{Example 1:}$ The graphic shows a section of a stochastic noise signal $x(t)$ whose instantaneous value can be taken as a continuous random variable $x$.

- From the »probability density function» $\rm (PDF)$ shown on the right, it can be seen that instantaneous values around the mean $m_1$ occur most frequently for any exemplary signal.

- Since there are no statistical dependencies between the samples $x_ν$, such a signal is often also referred to as »white noise«.

Definition of the probability density function

For a value-continuous random variable, the probabilities that it takes on quite specific values are zero. Therefore, to describe a value-continuous random variable, we must always refer to the »probability density function« $\rm (PDF)$.

$\text{Definition:}$ The value of the »probability density function« $f_{x}(x)$ at location $x_\mu$ is equal to the probability that the instantaneous value of the random variable $x$ lies in an $($infinitesimally small$)$ interval of width $Δx$ around $x_\mu$, divided by $Δx$:

- $$f_x(x=x_\mu) = \lim_{\rm \Delta \it x \hspace{0.05cm}\to \hspace{0.05cm}\rm 0}\frac{\rm Pr \{\it x_\mu-\rm \Delta \it x/\rm 2 \le \it x \le x_\mu \rm +\rm \Delta \it x/\rm 2\} }{\rm \Delta \it x}.$$

This extremely important descriptive variable has the following properties:

- Although from the time course in $\text{Example 1}$ it can be seen that the most frequent signal components lie at $x = m_1$ and the PDF has its largest value here, for a value-continuous random variable the probability ${\rm Pr}(x = m_1)$, that the instantaneous value is exactly equal to the mean $m_1$, is identically zero.

- The probability that the random variable lies in the range between $x_{\rm u}$ and $x_{\rm o}$:

- $${\rm Pr}(x_{\rm u} \le x \le x_{\rm o})= \int_{x_{\rm u} }^{x_{\rm o} }f_{x}(x) \,{\rm d}x.$$

- As an important normalization property, this yields for the area under the PDF with the boundary transitions $x_{\rm u} → \hspace{0.05cm} - \hspace{0.05cm} ∞$ and $x_{\rm o} → +∞:$

- $$\int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} f_{x}(x) \,{\rm d}x = \rm 1.$$

- The corresponding equation for value-discrete, $M$-level random variables states that the sum over the $M$ occurrence probabilities gives the value $1$.

$\text{Note on nomenclature:}$

In the literature, a distinction is often made between the random variable $X$ and its realizations $x ∈ X$. Thus, the above definition equation is

- $$f_{X}(X=x) = \lim_{ {\rm \Delta} x \hspace{0.05cm}\to \hspace{0.05cm} 0}\frac{ {\rm Pr} \{ x - {\rm \Delta} x/2 \le X \le x +{\rm \Delta} x/ 2\} }{ {\rm \Delta} x}.$$

We have largely dispensed with this more precise nomenclature in our $\rm LNTwww$ so as not to use up two letters for one quantity.

- Lowercase letters $($as $x)$ often denote signals and uppercase letters $($as $X)$ the associated spectra in our case.

- Nevertheless, today (2017) we have to honestly admit that the 2001 decision was not entirely happy.

PDF definition for discrete random variables

For reasons of a uniform representation of all random variables $($both value-discrete and value-continuous$)$, it is convenient to define the probability density function also for value-discrete random variables.

$\text{Definition:}$ Applying the definition equation of the last section to value-discrete random variables, the PDF takes infinitely large values at some points $x_\mu$ due to the nonvanishingly small probability value and the limit transition $Δx → 0$.

Thus, the PDF results in a sum of »Dirac delta functions« ⇒ »distributions«:

- $$f_{x}(x)=\sum_{\mu=1}^{M}p_\mu\cdot {\rm \delta}( x-x_\mu).$$

The weights of these Dirac delta functions are equal to the probabilities $p_\mu = {\rm Pr}(x = x_\mu$).

Here is another note to help classify the different descriptive quantities for value-discrete and value-continuous random variables: Probability and probability density function are related in a similar way as in the book »Signal Representation«

- a discrete spectral component of a harmonic oscillation ⇒ line spectrum, and

- a continuous spectrum of an energy-limited $($pulse-shaped$)$ signal.

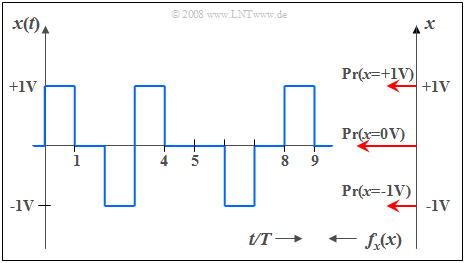

$\text{Example 2:}$ Below you can see a section

- of a rectangular signal with three possible values,

- where the signal value $0 \ \rm V$ occurs twice as often as the outer signal values $(\pm 1 \ \rm V)$.

Thus, the corresponding PDF $($values from top to bottom$)$:

- $$f_{x}(x) = 0.25 \cdot \delta(x - {\rm 1 V})+ 0.5\cdot \delta(x) + 0.25\cdot \delta (x + 1\rm V).$$

⇒ For a more in-depth look at the topic covered here, we recommend the following $($German language$)$ learning video:

- »Wahrscheinlichkeit und WDF« ⇒ »Probability and probability density function«

Numerical determination of the PDF

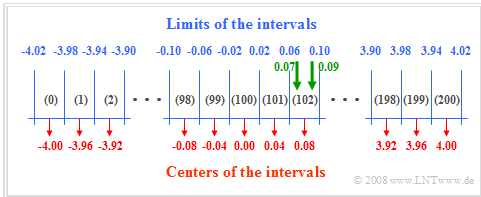

You can see here a scheme for the numerical determination of the probability density function. Assuming that the random variable $x$ at hand has negligible values outside the range from $x_{\rm min} = -4.02$ to $x_{\rm max} = +4.02$, proceed as follows:

- Divide the range of $x$-values into $I$ intervals of equal width $Δx$ and define a field PDF$[0 : I-1]$. In the sketch $I = 201$ and accordingly $Δx = 0.04$ is chosen.

- The random variable $x$ is now called $N$ times in succession, each time checking to which interval $i_{\rm act}$ the current random variable $x_{\rm act}$ belongs:

$i_{\rm act} = ({\rm int})((x + x_{\rm max})/Δx).$ - The corresponding field element PDF( $i_{\rm act}$) is then incremented by $1$.

- After $N$ iterations, PDF$[i_{\rm act}]$ then contains the number of random numbers belonging to the interval $i_{\rm act}$.

- The actual PDF values are obtained if, at the end, all field elements PDF$[i]$ with $0 ≤ i ≤ I-1$ are still divided by $N \cdot Δx$.

$\text{Example 3:}$ From the drawn green arrows in the graph above, one can see:

- The value $x_{\rm act} = 0.07$ leads to the result $i_{\rm act} =$ (int) ((0.07 + 4.02)/0.04) = (int) $102.25$.

- Here »(int)« means an integer conversion after float division ⇒ $i_{\rm act} = 102$.

- The same interval $i_{\rm act} = 102$ results for $0.06 < x_{\rm act} < 0.10$, so for example also for $x_{\rm act} = 0.09$.

Exercises for the chapter

Exercise 3.1: Cosine-square PDF and PDF with Dirac Functions