Difference between revisions of "Information Theory/AWGN Channel Capacity for Discrete-Valued Input"

| Line 187: | Line 187: | ||

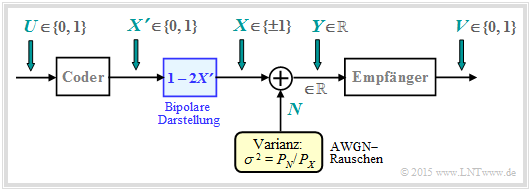

The diagram shows the underlying block diagram for [[Digital_Signal_Transmission/Lineare_digitale_Modulation_–_Kohärente_Demodulation#Gemeinsames_Blockschaltbild_f.C3.BCr_ASK_und_BPSK|Binary Phase Shift Keying]] (BPSK) with binary input $U$ and binary output $V$. The best possible coding is to achieve that the error probability $\text{Pr}(V ≠ U)$ becomes vanishingly small. | The diagram shows the underlying block diagram for [[Digital_Signal_Transmission/Lineare_digitale_Modulation_–_Kohärente_Demodulation#Gemeinsames_Blockschaltbild_f.C3.BCr_ASK_und_BPSK|Binary Phase Shift Keying]] (BPSK) with binary input $U$ and binary output $V$. The best possible coding is to achieve that the error probability $\text{Pr}(V ≠ U)$ becomes vanishingly small. | ||

| − | * | + | *The coder output is characterized by the binary random variable $X \hspace{0.03cm}' = \{0, 1\}$ ⇒ $M_{X'} = 2$, while the output $Y$ of the AWGN channel remains continuous-valued: $M_Y → ∞$. |

| − | * | + | *Mapping $X = 1 - 2X\hspace{0.03cm} '$ takes us from the unipolar representation to the bipolar (antipodal) description more suitable for BPSK: $X\hspace{0.03cm} ' = 0 → \ X = +1; \hspace{0.5cm} X\hspace{0.03cm} ' = 1 → X = -1$. |

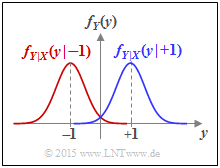

| − | [[File:P_ID2942__Inf_T_4_3_S5b_neu.png|right|frame| | + | [[File:P_ID2942__Inf_T_4_3_S5b_neu.png|right|frame|Conditional WDF for <br>$-1$ (red) and $+1$ (blue) ]] |

| − | * | + | *The AWGN channel is characterised by two conditional probability density functions: |

:$$f_{Y\hspace{0.05cm}|\hspace{0.03cm}{X}}(y\hspace{0.05cm}|\hspace{0.03cm}{X}=+1) =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\sigma^2}} \cdot {\rm exp}\left [-\frac{(y - 1)^2} { 2 \sigma^2})\right ] \hspace{0.05cm}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.5cm}\text{Kurzform:} \ \ f_{Y\hspace{0.05cm}|\hspace{0.03cm}{X}}(y\hspace{0.05cm}|\hspace{0.03cm}+1)\hspace{0.05cm},$$ | :$$f_{Y\hspace{0.05cm}|\hspace{0.03cm}{X}}(y\hspace{0.05cm}|\hspace{0.03cm}{X}=+1) =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\sigma^2}} \cdot {\rm exp}\left [-\frac{(y - 1)^2} { 2 \sigma^2})\right ] \hspace{0.05cm}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.5cm}\text{Kurzform:} \ \ f_{Y\hspace{0.05cm}|\hspace{0.03cm}{X}}(y\hspace{0.05cm}|\hspace{0.03cm}+1)\hspace{0.05cm},$$ | ||

:$$f_{Y\hspace{0.05cm}|\hspace{0.03cm}{X}}(y\hspace{0.05cm}|\hspace{0.03cm}{X}=-1) =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\sigma^2}} \cdot {\rm exp}\left [-\frac{(y + 1)^2} { 2 \sigma^2})\right ] \hspace{0.05cm}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.5cm}\text{Kurzform:} \ \ f_{Y\hspace{0.05cm}|\hspace{0.03cm}{X}}(y\hspace{0.05cm}|\hspace{0.03cm}-1)\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | :$$f_{Y\hspace{0.05cm}|\hspace{0.03cm}{X}}(y\hspace{0.05cm}|\hspace{0.03cm}{X}=-1) =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\sigma^2}} \cdot {\rm exp}\left [-\frac{(y + 1)^2} { 2 \sigma^2})\right ] \hspace{0.05cm}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.5cm}\text{Kurzform:} \ \ f_{Y\hspace{0.05cm}|\hspace{0.03cm}{X}}(y\hspace{0.05cm}|\hspace{0.03cm}-1)\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| − | * | + | *Since here the signal $X$ is normalised to $±1$ ⇒ power $1$ instead of $P_X$, the variance of the AWGN noise $N$ must be normalised in the same way: $σ^2 = P_N/P_X$. |

| − | * | + | *The receiver makes a [[Channel_Coding/Signal_classification#ML.E2.80.93Entscheidung_beim_AWGN.E2.80.93Kanal|maximum likelihood decision]] from the real-valued random variable $Y$ (at the AWGN channel output). The receiver output $V$ is binary $(0$ or $1)$. |

Revision as of 16:56, 24 April 2021

Contents

- 1 AWGN model for discrete-time band-limited signals

- 2 The channel capacity $C$ as a function of $E_{\rm S}/N_0$

- 3 System model for the interpretation of the AWGN channel capacity

- 4 The channel capacity $C$ as a function of $E_{\rm B}/N_0$

- 5 AWGN channel capacity for binary input signals

- 6 Vergleich zwischen Theorie und Praxis

- 7 Kanalkapazität des komplexen AWGN–Kanals

- 8 Maximale Coderate für QAM–Strukturen

- 9 Aufgaben zum Kapitel

- 10 Quellenverzeichnis

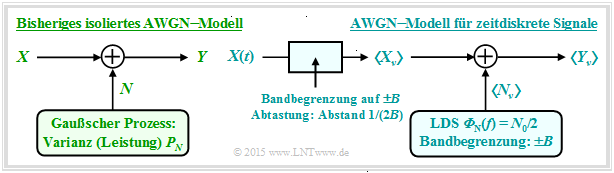

AWGN model for discrete-time band-limited signals

At the end of the last chapter , the AWGN model was used according to the left graph, characterised by the two random variables $X$ and $Y$ at the input and output and the stochastic noise $N$ as the result of a mean-free Gaussian random process ⇒ „White noise” with variance $σ_N^2$. The interference power $P_N$ is also equal toh $σ_N^2$.

The maximum mutual information $I(X; Y)$ between input and output ⇒ channel capacity $C$ is obtained when there is a Gaussian input PDF $f_X(x)$ vorliegt. With the transmit power $P_X = σ_X^2$ ⇒ variance of the random variable $X$ , the channel capacity equation is:

- $$C = 1/2 \cdot {\rm log}_2 \hspace{0.1cm} ( 1 + {P_X}/{P_N}) \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

Now we describe the AWGN channel model according to the case sketched on the right, where the sequence $〈X_ν〉$ is applied to the channel input, where the distance between successive values is $T_{\rm A}$ . This sequence is the discrete-time equivalent of the continuous-time signal $X(t)$ after band limiting and sampling.

The relationship between the two models can be established by means of a graph, which is described in more detail below.

The $\text{important insights}$ :

- In the right-hand model, the same relationship $Y_ν = X_ν + N_ν$ applies at the sampling times $ν·T_{\rm A}$ as in the left-hand model.

- The noise component $N_ν$ is now to be modelled by band-limited $($auf $±B)$ white noise with the two-sided power density ${\it Φ}_N(f) = N_0/2$ , where $B = 1/(2T_{\rm A})$ must hold ⇒ see sampling theorem.

$\text{ Interpretation:}$

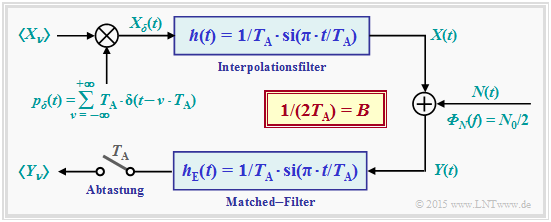

In the modified model, we assume an infinite sequence $〈X_ν〉$ of Gaussian random variables impressed on a Diracpuls $p_δ(t)$ . The resulting discrete-time signal is thus:

- $$X_{\delta}(t) = T_{\rm A} \cdot \hspace{-0.1cm} \sum_{\nu = - \infty }^{+\infty} X_{\nu} \cdot \delta(t- \nu \cdot T_{\rm A} )\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

The spacing of all (weighted) Dirac functions is uniform $T_{\rm A}$.

Through the interpolation filter with the impulse response $h(t)$ as well as the frequency response $H(f)$, where

- $$h(t) = 1/T_{\rm A} \cdot {\rm si}(\pi \cdot t/T_{\rm A}) \quad \circ\!\!\!-\!\!\!-\!\!\!-\!\!\bullet \quad H(f) = \left\{ \begin{array}{c} 1 \\ 0 \\ \end{array} \right. \begin{array}{*{20}c} {\rm{f\ddot{u}r}} \hspace{0.3cm} |f| \le B, \\ {\rm{f\ddot{u}r}} \hspace{0.3cm} |f| > B, \\ \end{array} \hspace{0.5cm} B = \frac{1}{T_{\rm A}}$$

must hold, the continuous-time signal $X(t)$ is obtained with the following properties:

- The samples $X(ν·T_{\rm A})$ are identical to the input values $X_ν$ for all integers $ν$ , which can be justified by the equidistant zeros of the sinc - function ⇒ $\text{si}(x) = \sin(x)/x$ .

- According to the sampling theorem, $X(t)$ is ideally bandlimited to the spectral range $±B$ , as the above calculation has shown ⇒ rectangular frequency response $H(f)$ of the one-sided bandwidth $B$.

$\text{Noise power:}$ After adding the noise $N(t)$ with the (two-sided) power density ${\it Φ}_N(t) = N_0/2$ , the matched filter $\rm (MF)$ with sinc–shaped impulse response follows. The following then applies to the noise power at the MF output :

- $$P_N = {\rm E}\big[N_\nu^2 \big] = \frac{N_0}{2T_{\rm A} } = N_0 \cdot B\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

$\text{Proof:}$ With $B = 1/(2T_{\rm A} )$ one obtains for the impulse response $h_{\rm E}(t)$ and the spectral function $H_{\rm E}(f)$:

- $$h_{\rm E}(t) = 2B \cdot {\rm si}(2\pi \cdot B \cdot t) \quad \circ\!\!\!-\!\!\!-\!\!\!-\!\!\bullet \quad H_{\rm E}(f) = \left\{ \begin{array}{c} 1 \\ 0 \\ \end{array} \right. \begin{array}{*{20}c} \text{für} \hspace{0.3cm} \vert f \vert \le B, \\ \text{für} \hspace{0.3cm} \vert f \vert > B. \\ \end{array} $$

It follows, according to the insights of theory of stochastic signals:

- $$P_N = \int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} \hspace{-0.3cm} {\it \Phi}_N (f) \cdot \vert H_{\rm E}(f)\vert^2 \hspace{0.15cm}{\rm d}f = \int_{-B}^{+B} \hspace{-0.3cm} {\it \Phi}_N (f) \hspace{0.15cm}{\rm d}f = \frac{N_0}{2} \cdot 2B = N_0 \cdot B \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

Further:

- If one samples the matched–filter output signal at equidistant intervals $T_{\rm A}$ , the same constellation as before results for the time instants $ν ·T_{\rm A}$ , namely: $Y_ν = X_ν + N_ν$.

- The noise component $N_ν$ in the discrete-time output signal $Y_ν$ is thus „band limited” and „white”. The channel capacity equation thus needs to be adjusted only slightly.

- With $\text{energy per symbol}$ $E_{\rm S} = P_X \cdot T_{\rm A}$ ⇒ transmission energy within a „symbol duration” $T_{\rm A}$ then holds:

- $$C = {1}/{2} \cdot {\rm log}_2 \hspace{0.1cm} ( 1 + \frac {P_X}{N_0 \cdot B}) = {1}/{2} \cdot {\rm log}_2 \hspace{0.1cm} ( 1 + \frac {2 \cdot P_X \cdot T_{\rm A}}{N_0}) = {1}/{2} \cdot {\rm log}_2 \hspace{0.1cm} ( 1 + \frac {2 \cdot E_{\rm S}}{N_0}) \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

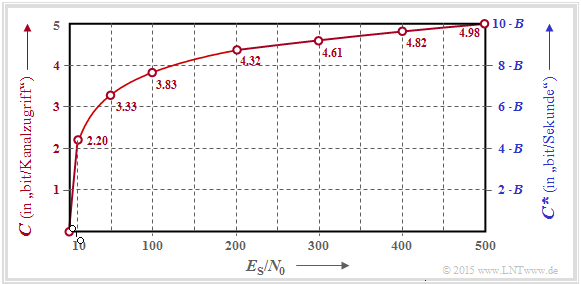

The channel capacity $C$ as a function of $E_{\rm S}/N_0$

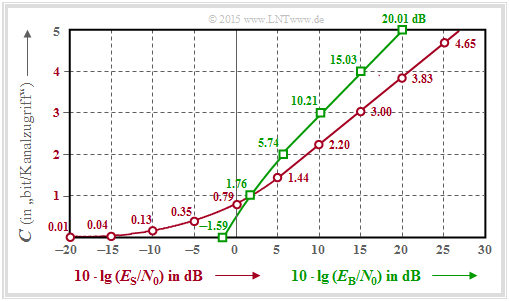

$\text{Example 1:}$ The graph shows the variation of the AWGN channel capacity as a function of the quotient $E_{\rm S}/N_0$, where the left coordinate axis and the red labels are valid:

- $$C = {1}/{2} \cdot {\rm log}_2 \hspace{0.1cm} ( 1 + \frac { 2 \cdot E_{\rm S} }{N_0}) \hspace{0.5cm}{\rm Einheit\hspace{-0.15cm}: \hspace{0.05cm}bit/Kanalzugriff\hspace{0.15cm} (englisch\hspace{-0.15cm}: \hspace{0.05cm}bit/channel\hspace{0.15cm}use)} \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

The (pseudo–)unit is sometimes also referred to as „bit/source symbol” or „bit/symbol” for short.

The right (blue) axis label takes into account the relation $B = 1/(2T_{\rm A})$ and thus provides an upper bound for the bit rate $R$ a digital system that is still possible for this AWGN channel.

- $$C^{\hspace{0.05cm}*} = \frac{C}{T_{\rm A} } = B \cdot {\rm log}_2 \hspace{0.1cm} ( 1 + \frac { 2 \cdot E_{\rm S} }{N_0}) \hspace{1.0cm}{\rm Einheit\hspace{-0.15cm}: \hspace{0.05cm}bit/second} \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

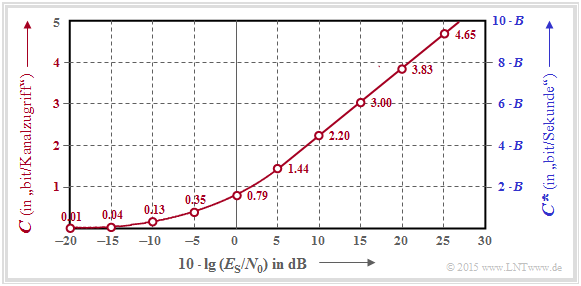

$\text{Example 2:}$ Often one gives the quotient of symbol energy $(E_{\rm S})$ and AWGN noise power density $(N_0)$ logarithmically.

- This graph shows the channel capacities $C$ and $C^{\hspace{0.05cm}*}$ respectively as a function of $10 · \lg (E_{\rm S}/N_0)$ in the range from $-20 \ \rm dB$ to $+30 \ \rm dB$.

- From about $10 \ \rm dB$ onwards, a (nearly) linear curve results here.

System model for the interpretation of the AWGN channel capacity

In order to discuss the channel coding theorem in the context of the AWGN channel, we still need an „encoder”, but here it is characterized in information-theoretic terms by the code rate $R$ alone.

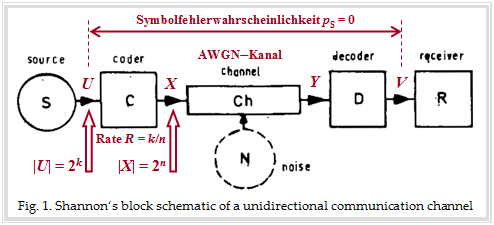

The graphic describes the message system considered by Shannon with the blocks source, coder, (AWGN) channel, decoder and receiver. In the background you can see an original picture from a paper about the Shannon theory. We have drawn in red some designations and explanations for the following text:

- The source symbol $U$ comes from an alphabet with $M_U = |U| = 2^k$ symbols and can be represented by $k$ equally probable statistically independent binary symbols.

- The alphabet of the code symbol $X$ has the symbol range $M_X = |X| = 2^n$, where $n$ results from the code rate $R = k/n$ .

- Thus, for code rate $R = 1$ , $n = k$ and the case $n > k$ leads to code rate $R < 1$.

$\rm Channel coding theorem$

This states that there is (at least) one code of rate $R$ that leads to symbol error probability $p_{\rm S} = \text{Pr}(V ≠ U) \equiv 0$ if the following conditions are satisfied:

- The code rate $R$ is not larger than the channel capacity $C$.

- Such a suitable code is infinitely long: $n → ∞$. Therefore, a Gaussian distribution $f_X(x)$ at the channel input is indeed possible, which has always been the basis of the previous calculation of the AWGN channel capacity:

- $$C = {1}/{2} \cdot {\rm log}_2 \hspace{0.1cm} ( 1 + \frac { 2 \cdot E_{\rm S} }{N_0}) \hspace{0.5cm}{\rm Einheit\hspace{-0.15cm}: \hspace{0.05cm}bit/channel use\hspace{0.15cm} } \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- Thus, the channel input quantity $X$ is continuous in value. The same is true for $U$ and for the quantities $Y$, $V$ after the AWGN channel.

- For a system comparison, however, the energy per symbol $(E_{\rm S} )$ is unsuitable. A comparison should rather be based on the energy $E_{\rm B}$ per information bit ⇒ $\text{Energie pro Bit}$ for short. Thus, with $E_{\rm B} = E_{\rm S}/R$ also holds:

- $$C = {1}/{2} \cdot {\rm log}_2 \hspace{0.1cm} ( 1 + \frac { 2 \cdot R \cdot E_{\rm B} }{N_0}) \hspace{0.2cm}{\rm Einheit\hspace{-0.15cm}: \hspace{0.05cm}bit/Kanalzugriff\hspace{0.1cm} (englisch\hspace{-0.15cm}: \hspace{0.05cm}bit/channel \hspace{0.15cm}use)} \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

These two equations are discussed on the next page.

The channel capacity $C$ as a function of $E_{\rm B}/N_0$

$\text{Example 3:}$ The graph for this example shows the AWGN channel capacity $C$ as a function

- of $10 · \lg (E_{\rm S}/N_0)$ ⇒ red curve:

- $$C = {1}/{2} \cdot {\rm log}_2 \hspace{0.1cm} ( 1 + \frac { 2 \cdot E_{\rm S} }{N_0}) \hspace{1.5cm}{\rm unit\hspace{-0.15cm}: \hspace{0.05cm}bit/channel use\hspace{0.15cm} (oder\hspace{-0.15cm}: \hspace{0.05cm}bit/Symbol)} \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

$\text{Red numbers:}$ Capacity $C$ in „$\rm bit/symbol$” for $10 · \lg (E_{\rm S}/N_0) = -20 \ \rm dB, -15 \ \rm dB$, ... , $+30\ \rm dB$.

- von $10 · \lg (E_{\rm B}/N_0)$ ⇒ green curve:

- $$C = {1}/{2} \cdot {\rm log}_2 \hspace{0.1cm} ( 1 + \frac { 2 \cdot R \cdot E_{\rm B} }{N_0}) \hspace{1.2cm}{\rm unit\hspace{-0.15cm}: \hspace{0.05cm}bit/channel use\hspace{0.1cm} (oder \hspace{-0.15cm}: \hspace{0.05cm}bit/Symbol)} \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

$\text{Green numbers:}$ Required $10 · \lg (E_{\rm B}/N_0)$ in „$\rm dB$” for $C = 0,\ 1$, ... , $5$ in „$\rm bit/symbol$”.

The detailed $C(E_{\rm B}/N_0)$ calculation can be found in rask 4.8 and the corresponding sample solution.

In the following, we interpret the (green) $C(E_{\rm B}/N_0)$ result in comparison to the (red) $C(E_{\rm S}/N_0)$ curve:

- Because of $E_{\rm S} = R · E_{\rm B}$ , the intersection of both curves is at $C (= R) = 1$ (bit/symbol). Required are $10 · \lg (E_{\rm S}/N_0) = 1.76\ \rm dB$ or $10 · \lg (E_{\rm B}/N_0) = 1.76\ \rm dB$ equally.

- In the range $C > 1$ the green curve always lies above the red curve. For example, for $10 · \lg (E_{\rm B}/N_0) = 20\ \rm dB$ the channel capacity is $C ≈ 5$, for $10 · \lg (E_{\rm S}/N_0) = 20\ \rm dB$ only $C = 3.83$.

- A comparison in horizontal direction shows that the channel capacity $C = 3$ bit/symbol is already achievable with $10 · \lg (E_{\rm B}/N_0) \approx 10\ \rm dB$ , but one needs $10 · \lg (E_{\rm S}/N_0) \approx 15\ \rm dB$ benötigt.

- In the range $C < 1$ , the red curve is always above the green one. For any $E_{\rm S}/N_0 > 0$ , $C > 0$. Thus, for logarithmic abscissa as in the present plot, the red curve extends to „minus infinity”.

- In contrast, the green curve ends at $E_{\rm B}/N_0 = \ln (2) = 0.693$ ⇒ $10 · \lg (E_{\rm B}/N_0)= -1.59 \rm dB$ ⇒ absolute limit for (error-free) transmission over the AWGN channel.

AWGN channel capacity for binary input signals

On the previous pages of this chapter we always assumed a Gaussian distributed, i.e. value continuous AWGN input $X$ according to Shannon theory. Now we consider the binary case and thus only now do justice to the title of the chapter „AWGN channel capacity with discrete value input” .

The diagram shows the underlying block diagram for Binary Phase Shift Keying (BPSK) with binary input $U$ and binary output $V$. The best possible coding is to achieve that the error probability $\text{Pr}(V ≠ U)$ becomes vanishingly small.

- The coder output is characterized by the binary random variable $X \hspace{0.03cm}' = \{0, 1\}$ ⇒ $M_{X'} = 2$, while the output $Y$ of the AWGN channel remains continuous-valued: $M_Y → ∞$.

- Mapping $X = 1 - 2X\hspace{0.03cm} '$ takes us from the unipolar representation to the bipolar (antipodal) description more suitable for BPSK: $X\hspace{0.03cm} ' = 0 → \ X = +1; \hspace{0.5cm} X\hspace{0.03cm} ' = 1 → X = -1$.

- The AWGN channel is characterised by two conditional probability density functions:

- $$f_{Y\hspace{0.05cm}|\hspace{0.03cm}{X}}(y\hspace{0.05cm}|\hspace{0.03cm}{X}=+1) =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\sigma^2}} \cdot {\rm exp}\left [-\frac{(y - 1)^2} { 2 \sigma^2})\right ] \hspace{0.05cm}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.5cm}\text{Kurzform:} \ \ f_{Y\hspace{0.05cm}|\hspace{0.03cm}{X}}(y\hspace{0.05cm}|\hspace{0.03cm}+1)\hspace{0.05cm},$$

- $$f_{Y\hspace{0.05cm}|\hspace{0.03cm}{X}}(y\hspace{0.05cm}|\hspace{0.03cm}{X}=-1) =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\sigma^2}} \cdot {\rm exp}\left [-\frac{(y + 1)^2} { 2 \sigma^2})\right ] \hspace{0.05cm}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.5cm}\text{Kurzform:} \ \ f_{Y\hspace{0.05cm}|\hspace{0.03cm}{X}}(y\hspace{0.05cm}|\hspace{0.03cm}-1)\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- Since here the signal $X$ is normalised to $±1$ ⇒ power $1$ instead of $P_X$, the variance of the AWGN noise $N$ must be normalised in the same way: $σ^2 = P_N/P_X$.

- The receiver makes a maximum likelihood decision from the real-valued random variable $Y$ (at the AWGN channel output). The receiver output $V$ is binary $(0$ or $1)$.

Ausgehend von diesem Modell berechnen wir nun die Kanalkapazität des AWGN–Kanals.

Diese lautet bei einer binären Eingangsgröße $X$ allgemein unter Berücksichtigung von $\text{Pr}(X = -1) = 1 - \text{Pr}(X = +1)$:

- $$C_{\rm BPSK} = \max_{ {\rm Pr}({X} =+1)} \hspace{-0.15cm} I(X;Y) \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

Aufgrund des symmetrischen Kanals ist offensichtlich, dass die Eingangswahrscheinlichkeiten

- $${\rm Pr}(X =+1) = {\rm Pr}(X =-1) = 0.5 $$

zum Optimum führen werden. Gemäß der Seite Transinformationsberechnung bei additiver Störung gibt es mehrere Berechnungsmöglichkeiten:

- $$ \begin{align*}C_{\rm BPSK} & = h(X) + h(Y) - h(XY)\hspace{0.05cm},\\ C_{\rm BPSK} & = h(Y) - h(Y|X)\hspace{0.05cm},\\ C_{\rm BPSK} & = h(X) - h(X|Y)\hspace{0.05cm}. \end{align*}$$

Alle Ergebnisse sind noch um die Pseudo–Einheit „bit/Kanalzugriff” zu ergänzen. Wir wählen hier die mittlere Gleichung:

- Die hierfür benötigte bedingte differentielle Entropie ist gleich

- $$h(Y\hspace{0.03cm}|\hspace{0.03cm}X) = h(N) = 1/2 \cdot {\rm log}_2 \hspace{0.1cm}(2\pi{\rm e}\cdot \sigma^2) \hspace{0.05cm}. $$

- Die differentielle Entropie $h(Y)$ ist vollständig durch die WDF $f_Y(y)$ gegeben. Mit den vorne definierten und skizzierten bedingten Wahrscheinlichkeitsdichtefunktionen erhält man:

- $$f_Y(y) = {1}/{2} \cdot \big [ f_{Y\hspace{0.03cm}|\hspace{0.03cm}{X}}(y\hspace{0.05cm}|\hspace{0.05cm}{X}=-1) + f_{Y\hspace{0.03cm}|\hspace{0.03cm}{X}}(y\hspace{0.05cm}|\hspace{0.05cm}{X}=+1) \big ]\hspace{0.3cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} h(Y) \hspace{-0.01cm}=\hspace{0.05cm} -\hspace{-0.7cm} \int\limits_{y \hspace{0.05cm}\in \hspace{0.05cm}{\rm supp}(f_Y)} \hspace{-0.65cm} f_Y(y) \cdot {\rm log}_2 \hspace{0.1cm} [f_Y(y)] \hspace{0.1cm}{\rm d}y \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

Es ist offensichtlich, dass $h(Y)$ nur durch numerische Integration ermittelt werden kann, insbesondere, wenn man berücksichtigt, dass sich $f_Y(y)$ im Überlappungsbereich aus der Summe der beiden bedingten Gauß–Funktionen ergibt.

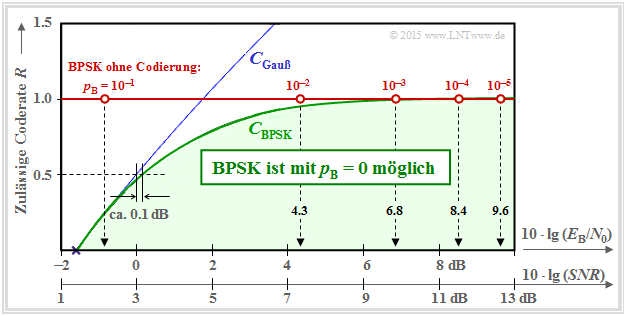

In der folgenden Grafik sind über der Abszisse $10 · \lg (E_{\rm B}/N_0)$ drei Kurven dargestellt:

- die blau gezeichnete Kanalkapazität $C_{\rm Gauß}$, gültig für eine Gaußsche Eingangsgröße $X$ ⇒ $M_X → ∞$,

- die grün gezeichnete Kanalkapazität $C_{\rm BPSK}$ für die Zufallsgröße $X = (+1, –1)$, sowie

- die mit „BPSK ohne Codierung” bezeichnete rote Horizontale.

Diese Kurvenverläufe sind wie folgt zu interpretieren:

- Die grüne Kurve $C_{\rm BPSK}$ gibt die maximal zulässige Coderate $R$ von Binary Phase Shift Keying (BPSK) an, bei der für das gegebene $E_{\rm B}/N_0$ durch bestmögliche Codierung die Bitfehlerwahrscheinlichkeit $p_{\rm B} \equiv 0$ möglich ist.

- Für alle BPSK–Systeme mit den Koordinaten $(10 · \lg \ E_{\rm B}/N_0, \ R)$ im „grünen Bereich” ist $p_{\rm B} \equiv 0$ prinzipiell erreichbar. Aufgabe der Nachrichtentechniker ist es, hierfür geeignete Codes zu finden.

- Die BPSK–Kurve liegt stets unter der absoluten Shannon–Grenzkurve $C_{\rm Gauß}$ für $M_X → ∞$ (blaue Kurve). Im unteren Bereich gilt $C_{\rm BPSK} ≈ C_{\rm Gauß}$. Zum Beispiel muss ein BPSK–System mit $R = 1/2$ nur ein um $0.1\ \rm dB$ größeres $E_{\rm B}/N_0$ bereitstellen, als es die (absolute) Kanalkapazität $C_{\rm Gauß}$ fordert.

- Ist $E_{\rm B}/N_0$ endlich, so gilt stets $C_{\rm BPSK} < 1$ ⇒ siehe Aufgabe 4.9Z. Eine BPSK mit $R = 1$ (und somit ohne Codierung) wird also stets eine Bitfehlerwahrscheinlichkeit $p_{\rm B} > 0$ zur Folge haben.

- Die Fehlerwahrscheinlichkeiten eines solchen BPSK–Systems ohne Codierung $($mit $R = 1)$ sind auf der roten Horizontalen angegeben. Um $p_{\rm B} ≤ 10^{–5}$ zu erreichen, benötigt man mindestens $10 · \lg (E_{\rm B}/N_0) = 9.6\ \rm dB$.

- Diese Wahrscheinlichkeiten ergeben sich gemäß dem Kapitel Fehlerwahrscheinlichkeit des optimalen BPSK-Systems im Buch „Digitalsignalübertragung” zu

- $$p_{\rm B} = {\rm Q} \left ( \sqrt{S \hspace{-0.06cm}N\hspace{-0.06cm}R}\right ) \hspace{0.45cm} {\rm mit } \hspace{0.45cm} S\hspace{-0.06cm}N\hspace{-0.06cm}R = 2\cdot E_{\rm B}/{N_0} \hspace{0.05cm}. $$

Hinweise:

- In obiger Grafik ist als zweite, zusätzliche Abszissenachse $10 · \lg (SNR)$ eingezeichnet.

- Die Funktion ${\rm Q}(x)$ bezeichnet man als die komplementäre Gaußsche Fehlerfunktion.

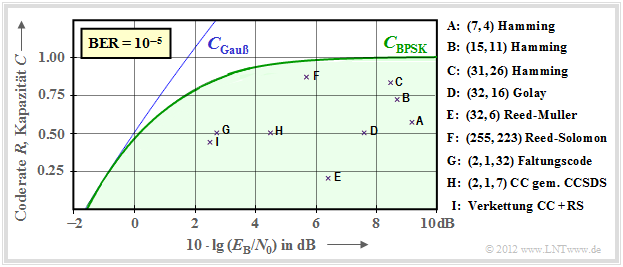

Vergleich zwischen Theorie und Praxis

Anhand zweier Grafiken soll gezeigt werden, in wie weit sich etablierte Kanalcodes der BPSK–Kanalkapazität (grüne Kurve) annähern. Als Ordinate aufgetragen ist die Rate $R = k/n$ dieser Codes bzw. die Kapazität $C$ (wenn noch die Pseudo–Einheit „bit/Kanalzugriff” hinzugefügt wird).

Vorausgesetzt ist:

- der AWGN–Kanal, gekennzeichnet durch $10 · \lg (E_{\rm B}/N_0)$ in dB, und

- für die durch Kreuze markierten realisierten Codes eine Bitfehlerrate (BER) von $10^{–5}$.

Zu beachten ist, dass die Kanalkapazitätskurven stets für $n → ∞$ und $\rm BER \equiv 0$ gelten.

- Würde man diese strenge Forderung „feherfrei” auch an die betrachteten Kanalcodes endlicher Codelänge $n$ anlegen, so wäre hierfür stets $10 · \lg \ (E_{\rm B}/N_0) \to \infty$ erforderlich.

- Dies ist aber ein eher akademisches Problem, also wenig praxisrelevant. Für $\text{BER} = 10^{–10}$ ergäbe sich eine qualitativ ähnliche Grafik.

$\text{Beispiel 4:}$ In der Grafik sind die Kenndaten von frühen Systemen mit Kanalcodierung und klassischer Decodierung angegeben.

- Es folgen einige Erläuterungen zu den Daten, die der Vorlesung [Liv10][1] entnommen wurden.

- Die Links bei diesen Erläuterungen beziehen sich oft auf das $\rm LNTwww$–Buch Channel Coding.

- Die Punkte $\rm A$, $\rm B$ und $\rm C$ markieren Hamming–Codes der Raten $R = 4/7 ≈ 0.57$, $R ≈ 0.73$ bzw. $R ≈ 0.84$. Für $\text{BER} = 10^{–5}$ benötigen diese sehr frühen Codes (aus dem Jahr 1950) alle $10 · \lg (E_{\rm B}/N_0) > 8\ \rm dB$.

- Die Markierung $\rm D$ kennzeichnet den binären Golay–Code mit der Rate $R = 1/2$ und der Punkt $\rm E$ einen Reed–Muller–Code. Dieser sehr niederratige Code kam bereits 1971 bei der Raumsonde Mariner 9 zum Einsatz.

- Die Reed–Solomon–Codes (RS–Codes, ca. 1960) sind eine Klasse zyklischer Blockcodes. $\rm F$ markiert einen RS–Code der Rate $223/255 \approx 0.875$ und einem erforderlichen $E_{\rm B}/N_0 < 6 \ \rm dB$.

- $\rm G$ und $\rm H$ bezeichnen zwei Faltungscodes $($englisch: Convolutional Codes, $\rm CC)$ mittlerer Rate. Der Code $\rm G$ wurde schon 1972 bei der Pioneer 10–Mission eingesetzt.

- Die Kanalcodierung der Voyager–Mission Ende der 1970er Jahre ist mit $\rm I$ markiert. Es handelt sich um die Verkettung eines $\text{(2, 1, 7)}$–Faltungscodes mit einem Reed–Solomon–Code.

Anzumerken ist, dass bei den Faltungscodes der dritte Kennungsparameter eine andere Bedeutung hat als bei den Blockcodes. So weist beispielsweise die Kennung $\text{(2, 1, 32)}$ auf das Memory $m = 32$ hin.

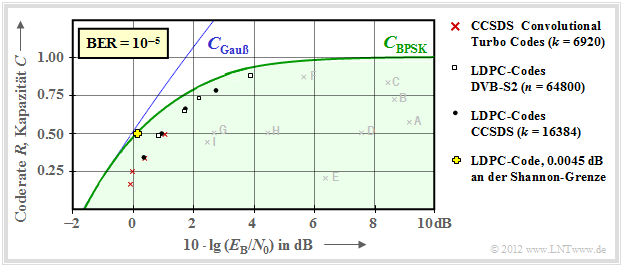

$\text{Beispiel 5:}$ Die im $\text{Beispiel 4}$ genannten frühen Kanalcodes liegen noch relativ weit von der Kanalkapazitätskurve entfernt.

Dies war wahrscheinlich auch ein Grund, warum dem Autor dieses Lerntutorials die auch große praktische Bedeutung der Informationstheorie verschlossen blieb, als er diese Anfang der 1970er Jahre im Studium kennengelernt hat.

Die Sichtweise hat sich deutlich verändert, als in den 1990er Jahren sehr lange Kanalcodes zusammen mit iterativer Decodierung aufkamen. Die neuen Markierungspunkte liegen deutlich näher an der Kapazitätsgrenzkurve.

Hier noch einige Erläuterungen zu dieser Grafik:

- Rote Kreuze markieren die so genannten Turbo–Codes nach $\rm CCSDS$ (Consultative Committee for Space Data Systems) mit jeweils $k = 6920$ Informationsbit und unterschiedlichen Codelängen $n = k/R$. Diese von Claude Berrou um 1990 erfundenen Codes können iterativ decodiert werden. Die (roten) Markierungen liegen jeweils weniger als $1 \ \rm dB$ von der Shannon–Grenze entfernt.

- Ähnlich verhalten sich die LDPC–Codes (Low Density Parity–check Codes) mit konstanter Codelänge $n = 64800$ ⇒ weiße Rechtecke). Sie werden seit 2006 bei DVB–S2 (Digital Video Broadcast over Satellite) eingesetzt und eignen sich aufgrund der spärlichen Einsen–Belegung der Prüfmatrix sehr gut für die iterative Decodierung mittels Faktor–Graphen und Exit Charts.

- Schwarze Punkte markieren die von $\rm CCSDS$ spezifizierten LDPC–Codes mit konstanter Anzahl an Informationsbits $(k = 16384)$ und variabler Wortlänge $n = k/R$. Diese Codeklasse erfordert ein ähnliches $E_{\rm B}/N_0$ wie die roten Kreuze und die weißen Rechtecke.

- Um das Jahr 2000 hatten viele Forscher den Ehrgeiz, sich der Shannon–Grenze bis auf Bruchteile von einem $\rm dB$ anzunähern. Das gelbe Kreuz markiert ein solches Ergebnis $(0.0045 \ \rm dB)$ von [CFRU01][2] mit einem irregulären LDPC–Code der Rate $ R =1/2$ und der Länge $n = 10^7$.

$\text{Fazit:}$ An dieser Stelle soll nochmals die Brillanz und der Weitblick von Claude E. Shannon hervorgehoben werden:

- Er hat 1948 eine bis dahin nicht bekannte Theorie entwickelt, mit der die Möglichkeiten, aber auch die Grenzen der Digitalsignalübertragung aufgezeigt werden.

- Zu dieser Zeit waren die ersten Überlegungen zur digitalen Nachrichtenübertragung gerade mal zehn Jahre alt ⇒ Pulscodemodulation (Alec Reeves, 1938) und selbst der Taschenrechner kam erst mehr als zwanzig Jahre später.

- Shannon's Arbeiten zeigen uns, dass man auch ohne gigantische Computer Großes leisten kann.

Kanalkapazität des komplexen AWGN–Kanals

Höherstufige Modulationsverfahren können jeweils durch eine Inphase– und eine Quadraturkomponente dargestellt werden. Hierzu gehören zum Beispiel

- die M–QAM ⇒ Quadraturamplitudenmodulation; $M ≥ 4$ quadratisch angeordnete Signalraumpunkte,

- die M–PSK ⇒ $M ≥ 4$ Signalraumpunkte in kreisförmiger Anordnung

Die beiden Komponenten lassen sich im äquivalenten Tiefpassbereich auch als Realteil bzw. Imaginärteil eines komplexen Rauschterms $N$ beschreiben.

- Alle oben genannten Verfahren sind zweidimensional.

- Der (komplexe) AWGN–Kanal stellt somit $K = 2$ voneinander unabhängige Gaußkanäle zur Verfügung.

- Entsprechend der Seite Parallele Gaußsche Kanäle ergibt sich deshalb für die Kapazität eines solchen Kanals:

- $$C_{\text{ Gauß, komplex} }= C_{\rm Gesamt} ( K=2) = {\rm log}_2 \hspace{0.1cm} ( 1 + \frac{P_X/2}{\sigma^2}) \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- $P_X$ bezeichnet die gesamte Nutzleistung von Inphase– und Quadraturkomponente.

- Dagegen bezieht sich die Varianz $σ^2$ der Störung nur auf eine Dimension: $σ^2 = σ_{\rm I}^2 = σ_{\rm Q}^2$.

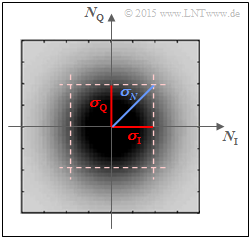

Die Skizze zeigt die 2D–WDF $f_N(n)$ des Gaußschen Rauschprozesses $N$ über den beiden Achsen

- $N_{\rm I}$ (Inphase–Anteil, Realteil) und

- $N_{\rm Q}$ (Quadraturanteil, Imaginärteil).

Dunklere Bereiche der rotationssymmetrischen WDF $f_N(n)$ um den Nullpunkt weisen auf mehr Störanteile hin. Für die Varianz des komplexen Gaußschen Rauschens $N$ gilt aufgrund der Rotationsinvarianz $(σ_{\rm I} = σ_{\rm Q})$ folgender Zusammenhang:

- $$\sigma_N^2 = \sigma_{\rm I}^2 + \sigma_{\rm Q}^2 = 2\cdot \sigma^2 \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

Damit lässt sich die Kanalkapazität auch wie folgt ausdrücken:

- $$C_{\text{ Gauß, komplex} }= {\rm log}_2 \hspace{0.1cm} ( 1 + \frac{P_X}{\sigma_N^2}) = {\rm log}_2 \hspace{0.1cm} ( 1 + SNR) \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

Die Gleichung wird auf der nächsten Seite numerisch ausgewertet. Man kann aber jetzt schon sagen, dass für das Signal–zu–Störleistungsverhältnis gelten wird:

- $$SNR = {P_X}/{\sigma_N^2} \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

Maximale Coderate für QAM–Strukturen

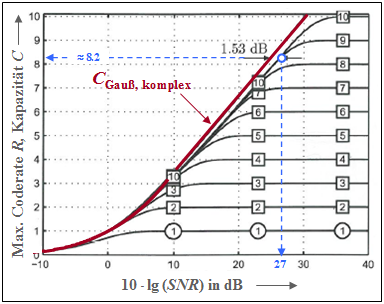

Die Grafik zeigt die Kapazität des komplexen AWGN–Kanals als rote Kurve:

- $$C_{\text{ Gauß, komplex} }= {\rm log}_2 \hspace{0.1cm} ( 1 + SNR) \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- Die Einheit dieser Kanalkapazität ist „bit/Kanalzugriff” oder „bit/Quellensymbol”.

- Als Abszisse bezeichnet das Signal–zu–Störleistungsverhältnis $10 · \lg (SNR)$ mit ${SNR} = P_X/σ_N^2$.

- Die Grafik wurde [Göb10][3] entnommen. Wir danken Bernhard Göbel, unserem ehemaligen Kollegen am LÜT, für sein Einverständnis, diese Abbildung verwenden zu dürfen, sowie für die große Unterstützung unseres Lerntutorials während seiner gesamten aktiven Zeit.

Die rote Kurve basiert entsprechend der Shannon–Theorie wieder auf einer Gaußverteilung $f_X(x)$ am Eingang. Zusätzlich eingezeichnet sind zehn weitere Kapazitätskurven für wertdiskreten Eingang:

- die Kurve für Binary Phase Shift Keying $($BPSK, mit „1” markiert ⇒ $K = 1)$,

- die $M$–stufige Quadratur–Amplitudenmodulation $($mit $M = 2^K, K = 2$, ... , $10)$.

Man erkennt aus dieser Darstellung:

- Die BPSK–Kurve und alle $M$–QAM–Kurven liegen rechts von der roten Shannon–Grenzkurve. Bei kleinem $SNR$ sind allerdings alle Kurven von der roten Kurve fast nicht mehr zu unterscheiden.

- Der Endwert aller Kurven für wertdiskrete Eingangssignale ist $K = \log_2 (M)$. Für $SNR \to ∞$ erhält man beispielsweise $C_{\rm BPSK} = 1 \ \rm bit/Symbol$ sowie $C_{\rm 4-QAM} = C_{\rm QPSK} = 2\ \rm bit/Symbol$.

- Die blauen Markierungen zeigen, dass eine $\rm 2^{10}–QAM$ mit $10 · \lg (SNR) ≈ 27 \ \rm dB$ eine Coderate von $R ≈ 8.2$ ermöglicht. Der Abstand zur Shannon–Kurve beträgt hier $1.53\ \rm dB$.

- Der Shaping Gain beträgt $10 · \lg (π \cdot {\rm e}/6) = 1.53 \ \rm dB$. Diese Verbesserung lässt sich erzielen, wenn man die Lage der $2^{10} = 32^2$ quadratisch angeordneten Signalraumpunkte so ändert, dass sich eine gaußähnliche Eingangs–WDF ergibt ⇒ Signal Shaping.

$\text{Fazit:}$ In der Aufgabe 4.10 werden die AWGN–Kapazitätskurven von BPSK und QPSK diskutiert:

- Ausgehend von der Abszisse $10 · \lg (E_{\rm B}/N_0)$ mit $E_{\rm B}$ (Energie pro Informationsbit) kommt man zur QPSK–Kurve durch Verdopplung der BPSK–Kurve:

- $$C_{\rm QPSK}\big [10 \cdot {\rm lg} \hspace{0.1cm}(E_{\rm B}/{N_0})\big ] = 2 \cdot C_{\rm BPSK}\big [10 \cdot {\rm lg} \hspace{0.1cm}(E_{\rm B}/{N_0}) \big ] .$$

- Vergleicht man aber BPSK und QPSK bei gleicher Energie $E_{\rm S}$ pro Informationssymbol, so gilt:

- $$C_{\rm QPSK}[10 \cdot {\rm lg} \hspace{0.1cm}(E_{\rm S}/{N_0})] = 2 \cdot C_{\rm BPSK}[10 \cdot {\rm lg} \hspace{0.1cm}(E_{\rm S}/{N_0}) - 3\,{\rm dB}] .$$

- Hierbei ist berücksichtigt, dass bei QPSK die Energie in einer Dimension nur $E_{\rm S}/2$ beträgt.

Aufgaben zum Kapitel

Aufgabe 4.8: Numerische Auswertung der AWGN-Kanalkapazität

Aufgabe 4.8Z: Was sagt die AWGN-Kanalkapazitätskurve aus?

Aufgabe 4.9: Höherstufige Modulation

Aufgabe 4.9Z: Ist bei BPSK die Kanalkapazität $C ≡ 1$ möglich?

Aufgabe 4.10: QPSK–Kanalkapazität

Quellenverzeichnis

- ↑ Liva, G.: Channel Coding. Vorlesungsmanuskript, Lehrstuhl für Nachrichtentechnik, TU München und DLR Oberpfaffenhofen, 2010.

- ↑ Chung S.Y; Forney Jr., G.D.; Richardson, T.J.; Urbanke, R.: On the Design of Low-Density Parity- Check Codes within 0.0045 dB of the Shannon Limit. – In: IEEE Communications Letters, vol. 5, no. 2 (2001), pp. 58–60.

- ↑ Göbel, B.: Information–Theoretic Aspects of Fiber–Optic Communication Channels. Dissertation. TU München. Verlag Dr. Hut, Reihe Informationstechnik, ISBN 978-3-86853-713-0, 2010.