Difference between revisions of "Channel Coding/General Description of Linear Block Codes"

(Die Seite wurde neu angelegt: „ {{Header |Untermenü=Binäre Blockcodes zur Kanalcodierung |Vorherige Seite=Beispiele binärer Blockcodes |Nächste Seite=Decodierung linearer Blockcodes }}…“) |

|||

| Line 46: | Line 46: | ||

<br>Außerdem ergibt sich auch dann ein gültiges Codewort, wenn man alle Bit invertiert: 0 ↔ 1. Auch das <u>0</u>–Wort (<i>n</i> mal eine „0”) und das <u>1</u>–Wort (<i>n</i> mal eine „1”) sind bei diesem Code zulässig.<br> | <br>Außerdem ergibt sich auch dann ein gültiges Codewort, wenn man alle Bit invertiert: 0 ↔ 1. Auch das <u>0</u>–Wort (<i>n</i> mal eine „0”) und das <u>1</u>–Wort (<i>n</i> mal eine „1”) sind bei diesem Code zulässig.<br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Codefestlegung durch die Prüfmatrix == | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | Wir betrachten den (7, 4, 3)–Hamming–Code mit Codeworten <i><u>x</u></i> der Länge <i>n</i> = 7, nämlich | ||

| + | [[File:P ID2355 KC T 1 3 S3.png|rahmenlos|rechts|(7, 4, 3)–Hamming–Code]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | *den <i>k</i> = 4 Informationsbits <i>x</i><sub>1</sub>, <i>x</i><sub>2</sub>, <i>x</i><sub>3</sub>, <i>x</i><sub>4</sub> , und<br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | *den <i>m</i> = 3 Prüfbits <i>x</i><sub>5</sub>, <i>x</i><sub>6</sub>, <i>x</i><sub>7</sub>.<br><br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Die Paritätsgleichungen lauten somit: | ||

| + | |||

| + | :<math>x_1 + x_2 + x_3 + x_5 \hspace{-0.1cm} = \hspace{-0.1cm} 0 \hspace{0.05cm},</math> | ||

| + | :<math>x_2 + x_3 + x_4 + x_6 \hspace{-0.1cm} = \hspace{-0.1cm} 0 \hspace{0.05cm},</math> | ||

| + | :<math>x_1 + x_2 + x_4 + x_7 \hspace{-0.1cm} = \hspace{-0.1cm} 0 \hspace{0.05cm}. </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | In der Matrixschreibweise lautet dieser Gleichungssatz: | ||

| + | |||

| + | :<math>{ \boldsymbol{\rm H}} \cdot \underline{x}^{\rm T}= \underline{0}^{\rm T} | ||

| + | \hspace{0.05cm}. </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | In dieser Gleichung werden verwendet: | ||

| + | *die Prüfmatrix <b>H</b> mit <i>m</i> = <i>n</i> – <i>k</i> = 3 Zeilen und <i>n</i> = 7 Spalten: | ||

| + | |||

| + | ::<math>{ \boldsymbol{\rm H}} = \begin{pmatrix} | ||

| + | 1 &1 &1 &0 &1 & 0 & 0\\ | ||

| + | 0 &1 &1 &1 &0 & 1 & 0\\ | ||

| + | 1 &1 &0 &1 &0 & 0 & 1 | ||

| + | \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm},</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | *das Codewort <i><u>x</u></i> = (<i>x</i><sub>1</sub>, <i>x</i><sub>2</sub>, ... , <i>x</i><sub>7</sub>) der Länge <i>n</i> = 7,<br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | *das Nullvektor <u>0</u> = (0, 0, 0) der Länge <i>m</i> = 3.<br><br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Durch Transponieren werden aus <i><u>x</u></i> und <u>0</u> die entsprechenden Spaltenvektoren <i><u>x</u></i><sup>T</sup> und <u>0</u><sup>T</sup>.<br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{Beispiel}}''':''' | ||

| + | [[File:P ID2356 KC T 1 4 S2.png|rahmenlos|rechts|(6, 3, 3)–Blockcode]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Die Grafik illustriert die <i>m</i> = 3 Paritätsgleichungen eines Codes <i>C</i> mit den Codeparametern <i>n</i> = 6 und <i>k</i> = 3 in der Reihenfolge rot, grün und blau. Entsprechend <b>H</b> · <i><u>x</u></i><sup>T</sup> = <u>0</u><sup>T</sup> lautet die Prüfmatrix: | ||

| + | |||

| + | :<math>{ \boldsymbol{\rm H}} = \begin{pmatrix} | ||

| + | 1 &1 &0 &1 &0 & 0\\ | ||

| + | 1 &0 &1 &0 &1 & 0\\ | ||

| + | 0 &1 &1 &0 &0 & 1 | ||

| + | \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Die 2<sup><i>k</i></sup> = 8 Worte einer systematischen Realisierung dieses Codes lauten (mit den Prüfbits rechts vom kleinen Pfeil): | ||

| + | |||

| + | :<math>\underline{x}_0 \hspace{-0.1cm} = \hspace{-0.1cm} (0, 0, 0_{\hspace{0.01cm} \rightarrow} 0, 0, 0)\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} \underline{x}_1 = (0, 0, 1_{\hspace{0.01cm} \rightarrow}0, 1, 1)\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm} | ||

| + | \underline{x}_2 = (0, 1, 0_{\hspace{0.01cm} \rightarrow}1, 0, 1)\hspace{0.05cm},</math> | ||

| + | :<math>\underline{x}_3 \hspace{-0.1cm} = \hspace{-0.1cm} (0, 1, 1_{\hspace{0.01cm} \rightarrow}1, 1, 0)\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm} | ||

| + | \underline{x}_4 = (1, 0, 0_{\hspace{0.01cm} \rightarrow} 1, 1, 0)\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} \underline{x}_5 = (1, 0, 1_{\hspace{0.01cm} \rightarrow}1, 0, 1)\hspace{0.05cm},</math> | ||

| + | :<math>\underline{x}_6 \hspace{-0.1cm} = \hspace{-0.1cm} (1, 1, 0_{\hspace{0.01cm} \rightarrow}0, 1, 1)\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} \underline{x}_7 = (1, 1, 1_{\hspace{0.01cm} \rightarrow}0, 0, 0)\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Man erkennt aus diesen Angaben: | ||

| + | *Die Anzahl der Spalten von <b>H</b> ist gleich der Codelänge <i>n</i>.<br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Die Anzahl der Zeilen von <b>H</b> ist gleich der Anzahl <i>m</i> = <i>n</i> – <i>k</i> der Prüfgleichungen.<br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Aus <b>H</b> · <i><u>x</u></i><sup>T</sup> = <u>0</u> folgt nicht, dass alle Codeworte eine gerade Anzahl von Einsen beinhalten.{{end}}<br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

Revision as of 19:23, 9 January 2017

Lineare Codes und zyklische Codes

Alle bisher behandelten Codes – Single Parity–check Code, Repetition Code und Hamming–Code – sind linear. Nun wird die für binäre Blockcodes gültige Definition von Linearität nachgereicht.

\[\underline{x}, \underline{x}\hspace{0.05cm}' \in {\rm GF}(2^n),\hspace{0.3cm} \underline{x}, \underline{x}\hspace{0.05cm}' \in \mathcal{C} \hspace{0.3cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}\underline{x} + \underline{x}\hspace{0.05cm}' \in \mathcal{C} \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

Diese Bedingung muss auch für x = x' erfüllt sein.

Hinweis: Die Modulo–Addition wird nun nicht mehr durch das Modulo–Additionszeichen ausgedrückt, sondern mit dem herkömmlichen Pluszeichen. Diese Vereinfachung der Schreibweise wird für den Rest dieses Buches beibehalten.

\[\mathcal{C}_1 = \{ (0, 0, 0) \hspace{0.05cm}, (0, 1, 1) \hspace{0.05cm},(1, 0, 1) \hspace{0.05cm},(1, 1, 0) \}\hspace{0.05cm},\]

\[\mathcal{C}_2 = \{ (0, 0, 0) \hspace{0.05cm}, (0, 1, 1) \hspace{0.05cm},(1, 1, 0) \hspace{0.05cm},(1, 1, 1) \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

Man erkennt:

- Der Code C1 ist linear, da die Modulo–2–Addition zweier beliebiger Codeworte stets auch ein gültiges Codewort ergibt, zum Beispiel (0, 1, 1) + (1, 0, 1) = (1, 1, 0).

- Die obige Definition gilt auch für die Modulo–2–Addition eines Codewortes mit sich selbst, zum Beispiel (0, 1, 1) + (0, 1, 1) = (0, 0, 0) ⇒ Jeder lineare Code beinhaltet das Nullwort.

- Obwohl die letzte Voraussetzung erfüllt wird, ist C2 kein linearer Code. Für diesen Code gilt nämlich beispielsweise: (0, 1, 1) + (1, 1, 0) = (1, 0, 1). Dies ist kein gültiges Codewort von C2.

Im Folgenden beschränken wir uns ausschließlich auf lineare Codes, da nichtlineare Codes für die Praxis von untergeordneter Bedeutung sind.

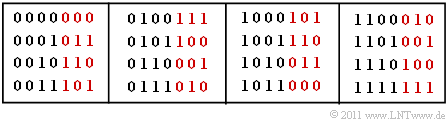

Man erkennt aus der Tabelle für den HC (7, 4, 3), dass dieser linear und zyklisch ist (schwarz: 4 Informationsbit, rot: n – k = 3 Prüfbit).

Außerdem ergibt sich auch dann ein gültiges Codewort, wenn man alle Bit invertiert: 0 ↔ 1. Auch das 0–Wort (n mal eine „0”) und das 1–Wort (n mal eine „1”) sind bei diesem Code zulässig.

Codefestlegung durch die Prüfmatrix

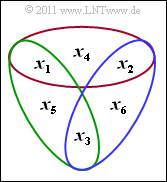

Wir betrachten den (7, 4, 3)–Hamming–Code mit Codeworten x der Länge n = 7, nämlich

- den k = 4 Informationsbits x1, x2, x3, x4 , und

- den m = 3 Prüfbits x5, x6, x7.

Die Paritätsgleichungen lauten somit:

\[x_1 + x_2 + x_3 + x_5 \hspace{-0.1cm} = \hspace{-0.1cm} 0 \hspace{0.05cm},\] \[x_2 + x_3 + x_4 + x_6 \hspace{-0.1cm} = \hspace{-0.1cm} 0 \hspace{0.05cm},\] \[x_1 + x_2 + x_4 + x_7 \hspace{-0.1cm} = \hspace{-0.1cm} 0 \hspace{0.05cm}. \]

In der Matrixschreibweise lautet dieser Gleichungssatz:

\[{ \boldsymbol{\rm H}} \cdot \underline{x}^{\rm T}= \underline{0}^{\rm T} \hspace{0.05cm}. \]

In dieser Gleichung werden verwendet:

- die Prüfmatrix H mit m = n – k = 3 Zeilen und n = 7 Spalten:

- \[{ \boldsymbol{\rm H}} = \begin{pmatrix} 1 &1 &1 &0 &1 & 0 & 0\\ 0 &1 &1 &1 &0 & 1 & 0\\ 1 &1 &0 &1 &0 & 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm},\]

- das Codewort x = (x1, x2, ... , x7) der Länge n = 7,

- das Nullvektor 0 = (0, 0, 0) der Länge m = 3.

Durch Transponieren werden aus x und 0 die entsprechenden Spaltenvektoren xT und 0T.

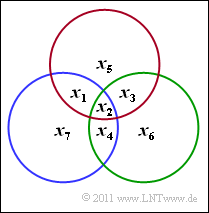

Die Grafik illustriert die m = 3 Paritätsgleichungen eines Codes C mit den Codeparametern n = 6 und k = 3 in der Reihenfolge rot, grün und blau. Entsprechend H · xT = 0T lautet die Prüfmatrix:

\[{ \boldsymbol{\rm H}} = \begin{pmatrix} 1 &1 &0 &1 &0 & 0\\ 1 &0 &1 &0 &1 & 0\\ 0 &1 &1 &0 &0 & 1 \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm}.\]

Die 2k = 8 Worte einer systematischen Realisierung dieses Codes lauten (mit den Prüfbits rechts vom kleinen Pfeil):

\[\underline{x}_0 \hspace{-0.1cm} = \hspace{-0.1cm} (0, 0, 0_{\hspace{0.01cm} \rightarrow} 0, 0, 0)\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} \underline{x}_1 = (0, 0, 1_{\hspace{0.01cm} \rightarrow}0, 1, 1)\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm} \underline{x}_2 = (0, 1, 0_{\hspace{0.01cm} \rightarrow}1, 0, 1)\hspace{0.05cm},\] \[\underline{x}_3 \hspace{-0.1cm} = \hspace{-0.1cm} (0, 1, 1_{\hspace{0.01cm} \rightarrow}1, 1, 0)\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm} \underline{x}_4 = (1, 0, 0_{\hspace{0.01cm} \rightarrow} 1, 1, 0)\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} \underline{x}_5 = (1, 0, 1_{\hspace{0.01cm} \rightarrow}1, 0, 1)\hspace{0.05cm},\] \[\underline{x}_6 \hspace{-0.1cm} = \hspace{-0.1cm} (1, 1, 0_{\hspace{0.01cm} \rightarrow}0, 1, 1)\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} \underline{x}_7 = (1, 1, 1_{\hspace{0.01cm} \rightarrow}0, 0, 0)\hspace{0.05cm}.\]

Man erkennt aus diesen Angaben:

- Die Anzahl der Spalten von H ist gleich der Codelänge n.

- Die Anzahl der Zeilen von H ist gleich der Anzahl m = n – k der Prüfgleichungen.

- Aus H · xT = 0 folgt nicht, dass alle Codeworte eine gerade Anzahl von Einsen beinhalten.