Difference between revisions of "Theory of Stochastic Signals/Binomial Distribution"

m (Text replacement - "”" to """) |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Header | {{Header | ||

| − | |Untermenü= | + | |Untermenü=Dicrete Random Variable |

| − | |Vorherige Seite= | + | |Vorherige Seite=Moments of a Discrete Random Variable |

|Nächste Seite=Poissonverteilung | |Nächste Seite=Poissonverteilung | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | == | + | ==General description of the binomial distribution== |

<br> | <br> | ||

{{BlaueBox|TEXT= | {{BlaueBox|TEXT= | ||

$\text{Definition:}$ | $\text{Definition:}$ | ||

| − | + | The '''binomial distribution''' represents an important special case for the occurrence probabilities of a discrete random variable. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | To derive the binomial distribution, we assume that $I$ binary and statistically independent random variables $b_i$ each can achieve | ||

| + | *the value $1$ with probability ${\rm Pr}(b_i = 1) = p$, and | ||

| + | *the value $0$ with probability ${\rm Pr}(b_i = 0) = 1-p$. | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | ||

| + | Then the sum $z$ is also a discrete random variable with the symbol set $\{0, \ 1, \ 2,\hspace{0.1cm}\text{ ...} \hspace{0.1cm}, \ I\}$, , which is called binomially distributed: | ||

| + | |||

:$$z=\sum_{i=1}^{I}b_i.$$ | :$$z=\sum_{i=1}^{I}b_i.$$ | ||

| − | + | Thus, the symbol size is $M = I + 1.$ }} | |

{{GraueBox|TEXT= | {{GraueBox|TEXT= | ||

| − | $\text{ | + | $\text{Example 1:}$ |

| − | + | The binomial distribution finds manifold applications in communications engineering as well as in other disciplines: | |

| − | # | + | # It describes the distribution of rejects in statistical quality control. |

| − | # | + | # It allows the calculation of the residual error probability in blockwise coding. |

| − | # | + | # Also the bit error rate of a digital transmission system obtained by simulation is actually a binomially distributed random quantity. |

| + | Probabilities of the binomial distribution.}} | ||

| − | == | + | ==Probabilities of the binomial distribution== |

<br> | <br> | ||

{{BlaueBox|TEXT= | {{BlaueBox|TEXT= | ||

| − | $\text{ | + | $\text{Calculation rule:}$ |

| − | + | For the '''probabilities of the binomial distribution''' with $μ = 0, \hspace{0.1cm}\text{...} \hspace{0.1cm}, \ I$: | |

:$$p_\mu = {\rm Pr}(z=\mu)={I \choose \mu}\cdot p\hspace{0.05cm}^\mu\cdot ({\rm 1}-p)\hspace{0.05cm}^{I-\mu}.$$ | :$$p_\mu = {\rm Pr}(z=\mu)={I \choose \mu}\cdot p\hspace{0.05cm}^\mu\cdot ({\rm 1}-p)\hspace{0.05cm}^{I-\mu}.$$ | ||

Der erste Term gibt hierbei die Anzahl der Kombinationen an $($sprich: $I\ \text{ über }\ μ)$: | Der erste Term gibt hierbei die Anzahl der Kombinationen an $($sprich: $I\ \text{ über }\ μ)$: | ||

Revision as of 21:47, 9 December 2021

Contents

General description of the binomial distribution

$\text{Definition:}$ The binomial distribution represents an important special case for the occurrence probabilities of a discrete random variable.

To derive the binomial distribution, we assume that $I$ binary and statistically independent random variables $b_i$ each can achieve

- the value $1$ with probability ${\rm Pr}(b_i = 1) = p$, and

- the value $0$ with probability ${\rm Pr}(b_i = 0) = 1-p$.

Then the sum $z$ is also a discrete random variable with the symbol set $\{0, \ 1, \ 2,\hspace{0.1cm}\text{ ...} \hspace{0.1cm}, \ I\}$, , which is called binomially distributed:

- $$z=\sum_{i=1}^{I}b_i.$$

Thus, the symbol size is $M = I + 1.$

$\text{Example 1:}$ The binomial distribution finds manifold applications in communications engineering as well as in other disciplines:

- It describes the distribution of rejects in statistical quality control.

- It allows the calculation of the residual error probability in blockwise coding.

- Also the bit error rate of a digital transmission system obtained by simulation is actually a binomially distributed random quantity.

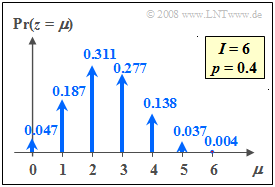

Probabilities of the binomial distribution.

Probabilities of the binomial distribution

$\text{Calculation rule:}$ For the probabilities of the binomial distribution with $μ = 0, \hspace{0.1cm}\text{...} \hspace{0.1cm}, \ I$:

- $$p_\mu = {\rm Pr}(z=\mu)={I \choose \mu}\cdot p\hspace{0.05cm}^\mu\cdot ({\rm 1}-p)\hspace{0.05cm}^{I-\mu}.$$

Der erste Term gibt hierbei die Anzahl der Kombinationen an $($sprich: $I\ \text{ über }\ μ)$:

- $${I \choose \mu}=\frac{I !}{\mu !\cdot (I-\mu) !}=\frac{ {I\cdot (I- 1) \cdot \ \cdots \ \cdot (I-\mu+ 1)} }{ 1\cdot 2\cdot \ \cdots \ \cdot \mu}.$$

Weitere Hinweise:

- Für sehr große Werte von $I$ kann die Binomialverteilung durch die im nächsten Abschnitt beschriebene Poissonverteilung angenähert werden.

- Ist gleichzeitig das Produkt $I · p \gg 1$, so geht nach dem Grenzwertsatz von de Moivre-Laplace die Poissonverteilung (und damit auch die Binomialverteilung) in eine diskrete Gaußverteilung über.

$\text{Beispiel 2:}$ Die Grafik zeigt die Wahrscheinlichkeiten der Binomialverteilung sind für $I =6$ und $p =0.4$. Von Null verschieden sind somit $M = I+1=7$ Wahrscheinlichkeiten.

Dagegen ergeben sich für $I = 6$ und $p = 0.5$ die folgenden Binomialwahrscheinlichkeiten:

- $$\begin{align*}{\rm Pr}(z\hspace{-0.05cm} =\hspace{-0.05cm}0) & = {\rm Pr}(z\hspace{-0.05cm} =\hspace{-0.05cm}6)\hspace{-0.05cm} =\hspace{-0.05cm} 1/64\hspace{-0.05cm} = \hspace{-0.05cm}0.015625 ,\\ {\rm Pr}(z\hspace{-0.05cm} =\hspace{-0.05cm}1) & = {\rm Pr}(z\hspace{-0.05cm} =\hspace{-0.05cm}5) \hspace{-0.05cm}= \hspace{-0.05cm}6/64 \hspace{-0.05cm}=\hspace{-0.05cm} 0.09375,\\ {\rm Pr}(z\hspace{-0.05cm} =\hspace{-0.05cm}2) & = {\rm Pr}(z\hspace{-0.05cm} =\hspace{-0.05cm}4)\hspace{-0.05cm} = \hspace{-0.05cm}15/64 \hspace{-0.05cm}= \hspace{-0.05cm}0.234375 ,\\ {\rm Pr}(z\hspace{-0.05cm} =\hspace{-0.05cm}3) & = 20/64 \hspace{-0.05cm}= \hspace{-0.05cm} 0.3125 .\end{align*}$$

Diese sind symmetrisch bezüglich des Abszissenwertes $\mu = I/2 = 3$.

Ein weiteres Beispiel für die Anwendung der Binomialverteilung ist die Berechnung der Blockfehlerwahrscheinlichkeit bei digitaler Übertragung.

$\text{Beispiel 3:}$ Überträgt man jeweils Blöcke von $I =10$ Binärsymbolen über einen Kanal, der

- mit der Wahrscheinlichkeit $p = 0.01$ ein Symbol verfälscht ⇒ Zufallsgröße $e_i = 1$, und

- entsprechend mit der Wahrscheinlichkeit $1 - p = 0.99$ das Symbol unverfälscht überträgt ⇒ Zufallsgröße $e_i = 0$,

so gilt für die neue Zufallsgröße $f$ ("Fehler pro Block"):

- $$f=\sum_{i=1}^{I}e_i.$$

Diese Zufallsgröße $f$ kann nun alle ganzzahligen Werte zwischen $0$ (kein Symbol verfälscht) und $I$ (alle Symbole falsch) annehmen. Die Wahrscheinlichkeiten für $\mu$ Verfälschungen bezeichnen wir mit $p_μ$.

- Der Fall, dass alle $I$ Symbole richtig übertragen werden, tritt mit der Wahrscheinlichkeit $p_0 = 0.99^{10} ≈ 0.9044$ ein. Dies ergibt sich auch aus der Binomialformel für $μ = 0$ unter Berücksichtigung der Definition $10\, \text{ über }\, 0 = 1$.

- Ein einziger Symbolfehler $(f = 1)$ tritt mit folgender Wahrscheinlichkeit auf:

- $$p_1 = \rm 10\cdot 0.01\cdot 0.99^9\approx 0.0914.$$

- Der erste Faktor berücksichtigt, dass es für die Position eines einzigen Fehlers genau $10\, \text{ über }\, 1 = 10$ Möglichkeiten gibt. Die beiden weiteren Faktoren beücksichtigen, dass ein Symbol verfälscht und neun richtig übertragen werden müssen, wenn $f =1$ gelten soll.

- Für $f =2$ gibt es deutlich mehr Kombinationen, nämlich $10\, \text{ über }\, 2 = 45$, und man erhält

- $$p_2 = \rm 45\cdot 0.01^2\cdot 0.99^8\approx 0.0041.$$

Kann ein Blockcode bis zu zwei Fehler korrigieren, so ist die Restfehlerwahrscheinlichkeit

- $$p_{\rm R} = \it p_{\rm 3} \rm +\hspace{0.1cm}\text{ ...} \hspace{0.1cm} \rm + \it p_{\rm 10}\approx \rm 10^{-4},$$

oder

- $$p_{\rm R} = \rm 1-\it p_{\rm 0}-\it p_{\rm 1}-p_{\rm 2}\approx \rm 10^{-4}.$$

- Man erkennt, dass die zweite Berechnungsmöglichkeit über das Komplement für große Werte von $I$ schneller zum Ziel führt.

- Man könnte aber auch als Näherung berücksichtigen, dass bei diesen Zahlenwerten $p_{\rm R} ≈ p_3$ gilt.

Mit dem interaktiven Applet Binomial– und Poissonverteilung können Sie die Binomialwahrscheinlichkeiten für beliebige $I$ und $p$ ermitteln.

Momente der Binomialverteilung

Die Momente kann man mit den Gleichungen der Kapitel Momente einer diskreten Zufallsgröße und Wahrscheinlichkeiten der Binomialverteilung allgemein berechnen.

$\text{Berechnungsvorschriften:} $ Für das Moment $k$-ter Ordnung einer binomialverteilten Zufallsgröße gilt allgemein:

- $$m_k={\rm E}\big[z^k\big]=\sum_{\mu={\rm 0} }^{I}\mu^k\cdot{I \choose \mu}\cdot p\hspace{0.05cm}^\mu\cdot ({\rm 1}-p)\hspace{0.05cm}^{I-\mu}.$$

Daraus erhält man nach einigen Umformungen für

- den linearen Mittelwert:

- $$m_1 ={\rm E}\big[z\big]= I\cdot p,$$

- den quadratischen Mittelwert:

- $$m_2 ={\rm E}\big[z^2\big]= (I^2-I)\cdot p^2+I\cdot p.$$

Die Varianz und die Streuung erhält man durch Anwendung des "Steinerschen Satzes":

- $$\sigma^2 = {m_2-m_1^2} = {I \cdot p\cdot (1-p)} \hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} \sigma = \sqrt{I \cdot p\cdot (1-p)}.$$

Die maximale Varianz $σ^2 = I/4$ ergibt sich für die "charakteristische Wahrscheinlichkeit" $p = 1/2$. In diesem Fall sind die Wahrscheinlichkeiten symmetrisch um den Mittelwert $m_1 = I/2 \ ⇒ \ p_μ = p_{I–μ}$.

Je mehr die charakteristische Wahrscheinlichkeit $p$ vom Wert $1/2$ abweicht,

- um so kleiner ist die Streuung $σ$, und

- um so unsymmetrischer werden die Wahrscheinlichkeiten um den Mittelwert $m_1 = I · p$.

$\text{Beispiel 4:}$ Wir betrachten wie im $\text{Beispiel 3}$ einen Block von $I =10$ Binärsymbolen, die jeweils mit der Wahrscheinlichkeit $p = 0.01$ unabhängig voneinander verfälscht werden. Dann gilt:

- Die mittlere Anzahl von Fehlern pro Block ist gleich $m_f = {\rm E}\big[ f\big] = I · p = 0.1$.

- Die Streuung (Standardabweichung) der Zufallsgröße $f$ beträgt $σ_f = \sqrt{0.1 \cdot 0.99}≈ 0.315$.

Im vollständig gestörten Kanal ⇒ Verfälschungswahrscheinlichkeit $p = 1/2$ ergeben sich demgegenüber die Werte

- $m_f = 5$ ⇒ im Mittel sind fünf der zehn Bit innerhalb eines Blocks falsch,

- $σ_f = \sqrt{I}/2 ≈1.581$ ⇒ maximale Streuung für $I = 10$.

Aufgaben zum Kapitel

Aufgabe 2.3: Summe von Binärzahlen

Aufgabe 2.4: Zahlenlotto (6 aus 49)