Difference between revisions of "Digital Signal Transmission/Block Coding with 4B3T Codes"

| Line 79: | Line 79: | ||

*In contrast, the 4B3T power-spectral density has zeros at $f = 0$ and multiples of $f = 1/T$. <br> | *In contrast, the 4B3T power-spectral density has zeros at $f = 0$ and multiples of $f = 1/T$. <br> | ||

*The zero point at $f = 0$ has the advantage that the 4B3T signal can also be transmitted without major losses via a so-called ''telephone channel'', which is not suitable for a DC signal due to transformers.<br> | *The zero point at $f = 0$ has the advantage that the 4B3T signal can also be transmitted without major losses via a so-called ''telephone channel'', which is not suitable for a DC signal due to transformers.<br> | ||

| − | * | + | *The zero point at $f = 1/T$ has the disadvantage that this makes clock recovery at the receiver more difficult. Outside of these zeros, the 4B3T codes have a flatter ${\it \Phi}_a(f)$ than the [[Digital_Signal_Transmission/Symbol-Wise_Coding_with_Pseudo_Ternary_Codes#Properties_of_the_AMI_code|AMI code]] discussed in the next chapter (blue curve), which is advantageous.<br> |

| − | * | + | *The reason for the flatter PSD curve at medium frequencies as well as the steeper drop towards the zeros is that for the 4B3T codes up to five $+1$– or $-1$ coefficients can follow each other. With the AMI code, these symbols occur only in isolation.<br> |

| − | == | + | == Error probability of the 4B3T codes== |

<br> | <br> | ||

Wir betrachten nun die Symbolfehlerwahrscheinlichkeit bei Verwendung des 4B3T–Codes im Vergleich zu redundanzfreier Binär– und Ternärcodierung, wobei folgende Voraussetzungen gelten sollen: | Wir betrachten nun die Symbolfehlerwahrscheinlichkeit bei Verwendung des 4B3T–Codes im Vergleich zu redundanzfreier Binär– und Ternärcodierung, wobei folgende Voraussetzungen gelten sollen: | ||

Revision as of 15:58, 19 April 2022

Contents

General description of block codes

In block coding each sequence of $m_q$ binary source symbols $(M_q = 2)$ is represented by a block of $m_c$ code symbols with symbol range $M_c$. In order to convert each source symbol sequence $\langle q_\nu \rangle$ into another code symbol sequence $\langle c_\nu \rangle$, the following condition must be satisfied:

- $$M_c^{\hspace{0.1cm}m_c} \ge M_q^{\hspace{0.1cm}m_q}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- For the redundancy-free codes discussed in the last chapter, the equal sign applies in this equation if $M_q$ is a power of two.

- Using the greater sign results in a redundant digital signal, and the relative code redundancy can be calculated as follows:

- $$r_c = 1- \frac{m_q \cdot {\rm log_2}\hspace{0.05cm} (M_q)}{m_c \cdot {\rm log_2} \hspace{0.05cm}(M_c)} > 0 \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

The best known block code for transmission coding is the 4B3T code with the code parameters

- $$m_q = 4,\hspace{0.2cm}M_q = 2,\hspace{0.2cm}m_c = 3,\hspace{0.2cm}M_c = 3\hspace{0.05cm},$$

which was developed in the 1970s and is used, for example, in ISDN (Integrated Services Digital Networks ).

A 4B3T code has the following properties:

- Because of $m_q \cdot T_{\rm B} = m_c \cdot T$, the symbol duration $T$ of the encoder signal is larger than the bit duration $T_{\rm B}$ of the binary source signal by a factor of $4/3$. This results in the favorable property that the bandwidth requirement is a quarter less than for redundancy-free binary transmission.

- The relative redundancy can be calculated with the above equation and results in $r_c \approx 16\%$. This redundancy is used in the 4B3T code to achieve equal signal freedom.

- The 4B3T coded signal can thus also be transmitted over a channel with the property $H_{\rm K}(f)= 0) = 0$ without noticeable degradation.

The recoding of the sixteen possible binary blocks into the corresponding ternary blocks could in principle be performed according to a fixed code table. To further improve the spectral properties of these codes, the common 4B3T codes, viz.

- the 4B3T code according to Jessop and Waters,

- the MS43 code (from: $\rm M$onitored $\rm S$um $\rm 4$B$\rm 3$T Code),

- the FoMoT code (from: $\rm Fo$ur $\rm Mo$de $\rm T$ernary),

two or more code tables are used, the selection of which is controlled by the running digital sum of the amplitude coefficients. The principle is explained in the next section.

Running digital sum

After the transmission of l coded blocks, the running digital sum with ternary amplitude coefficients $a_\nu \in \{ -1, 0, +1\}$:

- $${\it \Sigma}_l = \sum_{\nu = 1}^{3 \hspace{0.02cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm} l}\hspace{0.02cm} a_\nu \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

The selection of the table for coding the $(l + 1)$–th block is done depending on the current ${\it \Sigma}_l$ value.

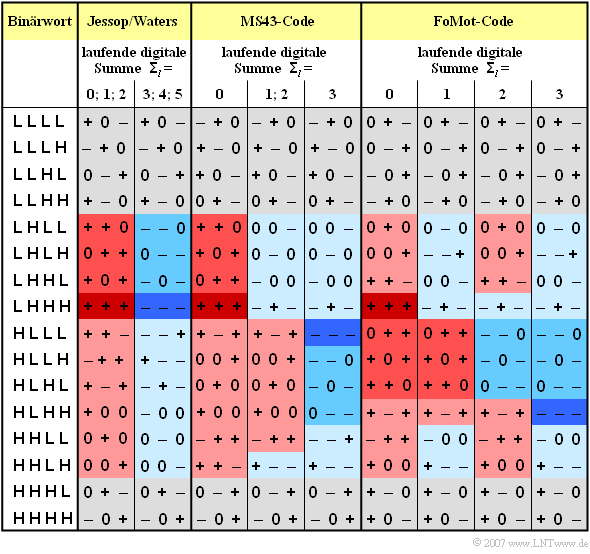

The table shows the coding rules for the three 4B3T codes mentioned above. o simplify the notation, "+" stands for the amplitude coefficient "+1" and "–" for the coefficient "–1".

- The two code tables of the Jessop–Waters code are selected in such a way that the running digital sum ${\it \Sigma}_l$ always lies between $0$ and $5$.

- For the other two codes (MS43, FoMoT), the restriction of the running digital sum to the value range $0 \le {\it \Sigma}_l \le 3$ is achieved by three and four alternative tables, respectively.

ACF and PSD of the 4B3T codes

The procedure for calculating ACF and PSD is only outlined here in bullet points:

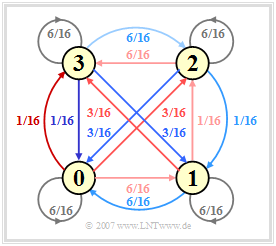

(1) The transition of the running digital sum from ${\it \Sigma}_l$ to ${\it \Sigma}_{l+1}$ is described by a homogeneous stationary first-order Markov chain with six (Jessop–Waters) or four states (MS43, FoMoT). For the FoMoT code, the Markov diagram sketched on the right applies.

(2) The values at the arrows denote the transition probabilities ${\rm Pr}({\it \Sigma}_{l+1}|{\it \Sigma}_{l})$ , resulting from the respective code tables. The colors correspond to the backgrounds of the table on the last section. Due to the symmetry of the FoMoT Markov diagram, the four probabilities are all the same:

- $${\rm Pr}({\it \Sigma}_{l} = 0) = \text{...} = {\rm Pr}({\it \Sigma}_{l} = 3) = 1/4.$$

(3) The auto-correlation function (ACF) $\varphi_a(\lambda) = {\rm E}\big [a_\nu \cdot a_{\nu+\lambda}\big ]$ of the amplitude coefficients can be determined from this diagram. Simpler than the analytical calculation, which requires a very large computational effort, is the simulative determination of the ACF values by computer.

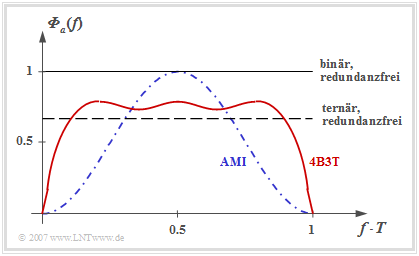

Fourier transforming the ACF yields the power-spectral density (PSD) ${\it \Phi}_a(f)$ of the amplitude coefficients corresponding to the following graph from [ST85][1]. The outlined PSD was determined for the FoMoT code, whose Markov diagram is shown above. The differences between the individual 4B3T codes are not particularly pronounced. Thus, for the MS43 code ${\rm E}\big [a_\nu^2 \big ] \approx 0.65$ and for the other two 4B3T codes (Jessop/Waters, MS43) ${\rm E}\big [a_\nu^2 \big ] \approx 0.69$.

The statements of this graph can be summarized as follows:

- The graph shows the PSD ${\it \Phi}_a(f)$ of the amplitude coefficients $a_\nu$ of the 4B3T code ⇒ red curve.

- The PSD ${\it \Phi}_s(f)$ including the basic transmission pulse is obtained by multiplying by $1/T \cdot |G_s(f)|^2$. For example, ${\it \Phi}_a(f)$ must be multiplied by a $\rm sinc^2$ function if $g_s(t)$ describes a rectangular pulse.

- Redundancy-free binary or ternary coding results in a constant ${\it \Phi}_a(f)$ in each case, the magnitude of which depends on the number of levels $M$ (different signal power).

- In contrast, the 4B3T power-spectral density has zeros at $f = 0$ and multiples of $f = 1/T$.

- The zero point at $f = 0$ has the advantage that the 4B3T signal can also be transmitted without major losses via a so-called telephone channel, which is not suitable for a DC signal due to transformers.

- The zero point at $f = 1/T$ has the disadvantage that this makes clock recovery at the receiver more difficult. Outside of these zeros, the 4B3T codes have a flatter ${\it \Phi}_a(f)$ than the AMI code discussed in the next chapter (blue curve), which is advantageous.

- The reason for the flatter PSD curve at medium frequencies as well as the steeper drop towards the zeros is that for the 4B3T codes up to five $+1$– or $-1$ coefficients can follow each other. With the AMI code, these symbols occur only in isolation.

Error probability of the 4B3T codes

Wir betrachten nun die Symbolfehlerwahrscheinlichkeit bei Verwendung des 4B3T–Codes im Vergleich zu redundanzfreier Binär– und Ternärcodierung, wobei folgende Voraussetzungen gelten sollen:

- Der Systemvergleich erfolgt zunächst unter der Nebenbedingung der "Spitzenwertbegrenzung". Deshalb verwenden wir den rechteckförmigen Sendegrundimpuls, der hierfür optimal ist.

- Der Gesamtfrequenzgang zeigt einen Cosinus–Rolloff mit bestmöglichem Rolloff–Faktor $r = 0.8$. Die Rauschleistung $\sigma_d^2$ ist somit um $12\%$ größer als beim Matched-Filter (globales Optimum), siehe Grafik auf der Seite Optimierung des Rolloff-Faktors bei Spitzenwertbegrenzung im dritten Hauptkapitel.

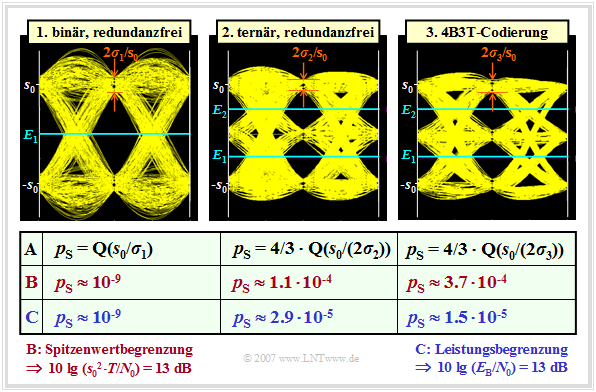

Die folgende Grafik zeigt die Augendiagramme (mit Rauschen) der drei zu vergleichenden Systeme und enthält zusätzlich in Zeile $\rm A$ die Gleichungen zur Berechnung der Fehlerwahrscheinlichkeit. Bei jedem Diagramm sind ca. 2000 Augenlinien gezeichnet.

Die beiden ersten Zeilen der Tabelle beschreiben den Systemvergleich bei Spitzenwertbegrenzung. Für das Binärsystem ergibt sich die Rauschleistung (unter Berücksichtigung der $12\%$–Erhöhung) zu

- $$\sigma_d^2 = 1.12 \cdot {N_0}/({2 \cdot T}) = 0.56 \cdot {N_0}/{T} = \sigma_1^2 \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

Für das Augendiagramm und die nachfolgenden Berechnungen ist jeweils ein "Störabstand" von $10 \cdot \lg \hspace{0.05cm}(s_0^2 \cdot T/N_0) = 13 \ \rm dB$ zugrunde gelegt. Damit erhält man:

- $$10 \cdot {\rm lg } \hspace{0.1cm}{s_0^2 \cdot T}/{N_0} = 13 \, {\rm dB } \hspace{0.3cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}{s_0^2 \cdot T}/{N_0} = 10^{1.3} \approx 20 \hspace{0.3cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}\sigma_1^2 = 0.56 \cdot {s_0^2}/{20} \approx 0.028 \cdot s_0^2 \hspace{0.3cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}{ \sigma_1}/{s_0}\approx 0.167 \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

In der Zeile $\rm B$ ist die dazugehörige Symbolfehlerwahrscheinlichkeit $p_{\rm S} \approx {\rm Q}(s_0/\sigma_1) \approx {\rm Q}(6) = 10^{-9}$ angegeben.

Die beiden weiteren Augendiagramme lassen sich wie folgt interpretieren:

- Beim redundanzfreien Ternärsystem ist die Augenöffnung nur halb so groß wie beim Binärsystem und die Rauschleistung $\sigma_2^2$ ist um den Faktor $\log_2 \hspace{0.05cm}(3)$ kleiner als $\sigma_1^2$.

- Der Faktor $4/3$ vor der Q–Funktion berücksichtigt, dass die ternäre "0" in beiden Richtungen verfälscht werden kann. Damit ergeben sich folgende Zahlenwerte:

- $$\frac{ \sigma_2}{s_0}\hspace{-0.05cm} =\hspace{-0.05cm} \frac{ \sigma_1/s_0}{\sqrt{{\rm log_2} (3)}}\hspace{-0.05cm} =\hspace{-0.05cm}\frac{ 0.167}{1.259} \approx 0.133 \hspace{0.3cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}p_{\rm S}\hspace{-0.05cm}=\hspace{-0.05cm} {4}/{3} \cdot {\rm Q}\left (\frac{ 0.5}{0.133}\right)\approx {4}/{3} \cdot {\rm Q}(3.76) \hspace{-0.05cm}= \hspace{-0.05cm}1.1 \cdot 10^{-4} .$$

- Der 4B3T–Code liefert noch etwas ungünstigere Ergebnisse, da hier bei gleicher Augenöffnung die Rauschleistung $(\sigma_3^2)$ weniger stark vermindert wird als beim redundanzfreien Ternärcode $(\sigma_2^2)$:

- $$\frac{ \sigma_3}{s_0} = \frac{ \sigma_1/s_0}{\sqrt{4/3}} =\frac{ 0.167}{1.155} \approx 0.145 \hspace{0.3cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}p_{\rm S}= {4}/{3} \cdot {\rm Q}\left (\frac{ 0.5}{0.145}\right)\approx {4}/{3} \cdot {\rm Q}(3.45) = 3.7 \cdot 10^{-4} \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

Die Symbolfehlerwahrscheinlichkeiten bei Leistungsbegrenzung sind für $10 \cdot \lg \hspace{0.05cm}(E_{\rm B}/N_0) = 13 \ \rm dB$ in der Zeile $\rm C$ angegeben:

- Beim Binärsystem mit NRZ–Rechteckimpulsen wird $p_{\rm S}$ gegenüber der Zeile $\rm B$ wegen $E_{\rm B} = s_0^2 \cdot T$ nicht verändert:

- $$p_\text{S, Leistungsbegrenzung} = p_\text{S, Spitzenwertbegrenzung} \approx 10^{-9}.$$

- Für die beiden Ternärcodes gilt ${\rm E}\big [a_\nu^2\big ] \approx 2/3$. Deshalb kann hier die Amplitude um den Faktor $\sqrt{(3/2)} \approx 1.225$ vergrößert werden.

- Für den redundanzfreien Ternärcode erhält man damit bei Leistungsbegrenzung eine um mehr als den Faktor $4$ kleinere Fehlerwahrscheinlichkeit als bei Spitzenwertbegrenzung (vgl. die Zeilen $\rm B$ und $\rm C$ in obiger Tabelle):

- $$p_\text{S, Leistungsbegrenzung} = 4/3 \cdot {\rm Q}(1.225 \cdot 3.76) \approx 2.9 \cdot 10^{-5} \approx 0.26 \cdot p_\text{S, Spitzenwertbegrenzung} .$$

- Ähnliches (und sogar noch verstärkt) gilt auch für den 4B3T-Code:

- $$p_\text{S, Leistungsbegrenzung} = 4/3 \cdot {\rm Q}(1.225 \cdot 3.45) \approx 1.5 \cdot 10^{-5} \approx 0.04 \cdot p_\text{S, Spitzenwertbegrenzung}.$$

Aufgaben zum Kapitel

Aufgabe 2.6: Modifizierter MS43-Code

Aufgabe 2.6Z: 4B3T-Code nach Jessop und Waters

Quellenverzeichnis

- ↑ Söder, G.; Tröndle, K.: Digitale Übertragungssysteme - Theorie, Optimierung & Dimensionierung der Basisbandsysteme. Berlin – Heidelberg: Springer, 1985.