Difference between revisions of "Theory of Stochastic Signals/Binomial Distribution"

| (28 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Header | {{Header | ||

| − | |Untermenü= | + | |Untermenü=Discrete Random Variable |

| − | |Vorherige Seite= | + | |Vorherige Seite=Moments of a Discrete Random Variable |

|Nächste Seite=Poissonverteilung | |Nächste Seite=Poissonverteilung | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | == | + | ==General description of the binomial distribution== |

<br> | <br> | ||

{{BlaueBox|TEXT= | {{BlaueBox|TEXT= | ||

$\text{Definition:}$ | $\text{Definition:}$ | ||

| − | + | The »'''binomial distribution'''« represents an important special case for the occurrence probabilities of a discrete random variable. | |

| − | + | To derive the binomial distribution, we assume that $I$ binary and statistically independent random variables $b_i$ each can achieve | |

| − | * | + | *the value $1$ with probability ${\rm Pr}(b_i = 1) = p$, and |

| − | |||

| − | + | *the value $0$ with probability ${\rm Pr}(b_i = 0) = 1-p$. | |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Then the sum $z$ is also a discrete random variable with the symbol set $\{0, \ 1, \ 2,\hspace{0.1cm}\text{ ...} \hspace{0.1cm}, \ I\}$, which is called binomially distributed: | ||

| − | |||

:$$z=\sum_{i=1}^{I}b_i.$$ | :$$z=\sum_{i=1}^{I}b_i.$$ | ||

| − | + | Thus, the symbol set size is $M = I + 1.$ }} | |

{{GraueBox|TEXT= | {{GraueBox|TEXT= | ||

| − | $\text{ | + | $\text{Example 1:}$ |

| − | + | The binomial distribution finds manifold applications in Communications Engineering as well as in other disciplines: | |

| − | + | # It describes the distribution of rejects in statistical quality control. | |

| − | + | # It allows the calculation of the residual error probability in blockwise coding. | |

| − | + | # The bit error rate of a digital transmission system obtained by simulation is actually a binomially distributed random quantity.}} | |

| − | == | + | ==Probabilities of the binomial distribution== |

<br> | <br> | ||

{{BlaueBox|TEXT= | {{BlaueBox|TEXT= | ||

| − | $\text{ | + | $\text{Calculation rule:}$ For the »'''probabilities of the binomial distribution'''« with $μ = 0, \hspace{0.1cm}\text{...} \hspace{0.1cm}, \ I$: |

| − | |||

:$$p_\mu = {\rm Pr}(z=\mu)={I \choose \mu}\cdot p\hspace{0.05cm}^\mu\cdot ({\rm 1}-p)\hspace{0.05cm}^{I-\mu}.$$ | :$$p_\mu = {\rm Pr}(z=\mu)={I \choose \mu}\cdot p\hspace{0.05cm}^\mu\cdot ({\rm 1}-p)\hspace{0.05cm}^{I-\mu}.$$ | ||

| − | + | The first term here indicates the number of combinations $($read: $I\ \text{ over }\ μ)$: | |

:$${I \choose \mu}=\frac{I !}{\mu !\cdot (I-\mu) !}=\frac{ {I\cdot (I- 1) \cdot \ \cdots \ \cdot (I-\mu+ 1)} }{ 1\cdot 2\cdot \ \cdots \ \cdot \mu}.$$}} | :$${I \choose \mu}=\frac{I !}{\mu !\cdot (I-\mu) !}=\frac{ {I\cdot (I- 1) \cdot \ \cdots \ \cdot (I-\mu+ 1)} }{ 1\cdot 2\cdot \ \cdots \ \cdot \mu}.$$}} | ||

| − | + | $\text{Additional notes:}$ | |

| − | + | #For very large values of $I$, the binomial distribution can be approximated by the [[Theory_of_Stochastic_Signals/Poisson_Distribution|»Poisson distribution«]] described in the next section. | |

| − | + | #If at the same time the product $I · p \gg 1$, then according to [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/De_Moivre%E2%80%93Laplace_theorem »de Moivre–Laplace's $($central limit$)$ theorem«], the Poisson distribution $($and hence the binomial distribution$)$ transitions to a discrete [[Theory_of_Stochastic_Signals/Gaussian_Distributed_Random_Variables|»Gaussian distribution«]]. | |

| − | [[File:P_ID203__Sto_T_2_3_S2_neu.png |frame| | + | {{GraueBox|TEXT= |

| − | + | [[File:P_ID203__Sto_T_2_3_S2_neu.png |frame|Binomial distribution probabilities]] | |

| − | $\text{ | + | $\text{Example 2:}$ |

| − | + | The graph shows the probabilities of the binomial distribution for $I =6$ and $p =0.4$. | |

| + | *Thus $M = I+1=7$ probabilities are different from zero. | ||

| − | + | *In contrast, for $I = 6$ and $p = 0.5$, the probabilities of the binomial distribution are as follows: | |

:$$\begin{align*}{\rm Pr}(z\hspace{-0.05cm} =\hspace{-0.05cm}0) & = {\rm Pr}(z\hspace{-0.05cm} =\hspace{-0.05cm}6)\hspace{-0.05cm} =\hspace{-0.05cm} 1/64\hspace{-0.05cm} = \hspace{-0.05cm}0.015625 ,\\ {\rm Pr}(z\hspace{-0.05cm} =\hspace{-0.05cm}1) & = {\rm Pr}(z\hspace{-0.05cm} =\hspace{-0.05cm}5) \hspace{-0.05cm}= \hspace{-0.05cm}6/64 \hspace{-0.05cm}=\hspace{-0.05cm} 0.09375,\\ {\rm Pr}(z\hspace{-0.05cm} =\hspace{-0.05cm}2) & = {\rm Pr}(z\hspace{-0.05cm} =\hspace{-0.05cm}4)\hspace{-0.05cm} = \hspace{-0.05cm}15/64 \hspace{-0.05cm}= \hspace{-0.05cm}0.234375 ,\\ {\rm Pr}(z\hspace{-0.05cm} =\hspace{-0.05cm}3) & = 20/64 \hspace{-0.05cm}= \hspace{-0.05cm} 0.3125 .\end{align*}$$ | :$$\begin{align*}{\rm Pr}(z\hspace{-0.05cm} =\hspace{-0.05cm}0) & = {\rm Pr}(z\hspace{-0.05cm} =\hspace{-0.05cm}6)\hspace{-0.05cm} =\hspace{-0.05cm} 1/64\hspace{-0.05cm} = \hspace{-0.05cm}0.015625 ,\\ {\rm Pr}(z\hspace{-0.05cm} =\hspace{-0.05cm}1) & = {\rm Pr}(z\hspace{-0.05cm} =\hspace{-0.05cm}5) \hspace{-0.05cm}= \hspace{-0.05cm}6/64 \hspace{-0.05cm}=\hspace{-0.05cm} 0.09375,\\ {\rm Pr}(z\hspace{-0.05cm} =\hspace{-0.05cm}2) & = {\rm Pr}(z\hspace{-0.05cm} =\hspace{-0.05cm}4)\hspace{-0.05cm} = \hspace{-0.05cm}15/64 \hspace{-0.05cm}= \hspace{-0.05cm}0.234375 ,\\ {\rm Pr}(z\hspace{-0.05cm} =\hspace{-0.05cm}3) & = 20/64 \hspace{-0.05cm}= \hspace{-0.05cm} 0.3125 .\end{align*}$$ | ||

| − | + | *These are symmetrical with respect to the abscissa value $\mu = I/2 = 3$.}} | |

| − | + | {{GraueBox|TEXT= | |

| + | $\text{Example 3:}$ Another example of the application of the binomial distribution is the »'''calculation of the block error probability in Digital Signal Transmission'''«. | ||

| − | + | If one transmits blocks each of $I =10$ binary symbols over a channel | |

| − | + | *with probability $p = 0.01$ that one symbol is falsified ⇒ random variable $e_i = 1$, and | |

| − | + | ||

| − | * | + | *correspondingly with probability $1 - p = 0.99$ for an unfalsified symbol ⇒ random variable $e_i = 0$, |

| − | * | ||

| − | + | then the new random variable $f$ ⇒ »number of block errors« is: | |

:$$f=\sum_{i=1}^{I}e_i.$$ | :$$f=\sum_{i=1}^{I}e_i.$$ | ||

| − | + | This random variable $f$ can take all integer values between $0$ $($no symbol is falsified$)$ and $I$ $($all symbols symbol are falsified$)$ . | |

| − | + | #We denote the probabilities for $\mu$ falsifications by $p_μ$. | |

| − | + | #The case where all $I$ symbols are correctly transmitted occurs with probability $p_0 = 0.99^{10} ≈ 0.9044$ . | |

| − | + | #This also follows from the binomial formula for $μ = 0$ considering the definition $10\, \text{ over }\, 0 = 1$. | |

| − | + | #A single symbol error $(f = 1)$ occurs with the probability $p_1 = \rm 10\cdot 0.01\cdot 0.99^9\approx 0.0914.$ | |

| − | + | #The first factor considers that there are exactly $10\, \text{ over }\, 1 = 10$ possibilities for the position of a single error. | |

| + | #The other two factors take into account that one symbol must be falsified and nine must be transmitted correctly if $f =1$ is to hold. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | For $f =2$ there are clearly more combinations, namely $10\, \text{ over }\, 2 = 45$, and we get | ||

:$$p_2 = \rm 45\cdot 0.01^2\cdot 0.99^8\approx 0.0041.$$ | :$$p_2 = \rm 45\cdot 0.01^2\cdot 0.99^8\approx 0.0041.$$ | ||

| − | + | If a block code can correct up to two errors, the »'''block error probability'''« is | |

| − | :$$p_{\rm | + | :$$p_{\rm block} = \it p_{\rm 3} \rm +\hspace{0.1cm}\text{ ...} \hspace{0.1cm} \rm + \it p_{\rm 10}\approx \rm 10^{-4},$$ |

| − | + | or | |

| − | :$$p_{\rm | + | :$$p_{\rm block} = \rm 1-\it p_{\rm 0}-\it p_{\rm 1}-p_{\rm 2}\approx \rm 10^{-4}.$$ |

| − | * | + | *One can see that for large $I$ values the second possibility of calculation via the complement leads faster to the goal. |

| − | * | + | |

| + | *However, one could also consider that for these numerical values $p_{\rm block} ≈ p_3$ holds as an approximation. }} | ||

| − | + | ⇒ Use the interactive HTML5/JS applet [[Applets:Binomial_and_Poisson_Distribution_(Applet)|»Binomial and Poisson distribution«]] to find the binomial probabilities for any $I$ and $p$ . | |

| − | == | + | ==Moments of the binomial distribution== |

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | + | You can calculate the moments in general using the equations in the chapters | |

| + | * [[Theory_of_Stochastic_Signals/Moments_of_a_Discrete_Random_Variable|»Moments of a Discrete Random Variable«]], | ||

| + | |||

| + | * [[Theory_of_Stochastic_Signals/Binomial_Distribution#Probabilities_of_the_binomial_distribution|»Probabilities of the Binomial Distribution»]]. | ||

| + | |||

{{BlaueBox|TEXT= | {{BlaueBox|TEXT= | ||

| − | $\text{ | + | $\text{Calculation rules:} $ For the »'''$k$-th order moment'''« of a binomially distributed random variable, the general rule is: |

:$$m_k={\rm E}\big[z^k\big]=\sum_{\mu={\rm 0} }^{I}\mu^k\cdot{I \choose \mu}\cdot p\hspace{0.05cm}^\mu\cdot ({\rm 1}-p)\hspace{0.05cm}^{I-\mu}.$$ | :$$m_k={\rm E}\big[z^k\big]=\sum_{\mu={\rm 0} }^{I}\mu^k\cdot{I \choose \mu}\cdot p\hspace{0.05cm}^\mu\cdot ({\rm 1}-p)\hspace{0.05cm}^{I-\mu}.$$ | ||

| + | From this, we obtain for after some transformations | ||

| + | *the first order moment ⇒ »linear mean«: | ||

| + | :$$m_1 ={\rm E}\big[z\big]= I\cdot p,$$ | ||

| + | *the second order moment ⇒ »power«: | ||

| + | :$$m_2 ={\rm E}\big[z^2\big]= (I^2-I)\cdot p^2+I\cdot p,$$ | ||

| + | *the variance by applying »Steiner's theorem»: | ||

| + | :$$\sigma^2 = {m_2-m_1^2} = {I \cdot p\cdot (1-p)} ,$$ | ||

| + | *the standard deviation: | ||

| + | :$$\sigma = \sqrt{I \cdot p\cdot (1-p)}.$$}} | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | The maximum variance $σ^2 = I/4$ is obtained for the »characteristic probability« $p = 1/2$. | |

| − | + | *In this case, the binomial probabilities are symmetric around the mean $m_1 = I/2 \ ⇒ \ p_μ = p_{I–μ}$. | |

| − | * | + | *The more the characteristic probability $p$ deviates from the value $1/2$ , |

| − | + | # the smaller is the standard deviation $σ$, and | |

| − | + | # the more asymmetric become the probabilities around the mean $m_1 = I · p$. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | {{GraueBox|TEXT= | |

| + | $\text{Example 4:}$ | ||

| − | + | As in $\text{Example 3}$, we consider a block of $I =10$ binary symbols, each of which is independently falsified with probability $p = 0.01$ . Then holds: | |

| − | + | *The mean number of block errors is equal to $m_f = {\rm E}\big[ f\big] = I · p = 0.1$. | |

| − | * | ||

| + | *The standard deviation of the random variable $f$ is $σ_f = \sqrt{0.1 \cdot 0.99}≈ 0.315$. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | In contrast, in the completely falsified channel ⇒ bit error probability $p = 1/2$ results in the values | ||

| + | |||

| + | *$m_f = 5$ ⇒ on average, five of the ten bits within a block are wrong, | ||

| − | + | * $σ_f = \sqrt{I}/2 ≈1.581$ ⇒ maximum standard deviation.}} | |

| − | |||

| − | * $σ_f = \sqrt{I}/2 ≈1.581$ ⇒ | ||

| − | == | + | ==Exercises for the chapter== |

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | [[Aufgaben: | + | [[Aufgaben:Exercise_2.3:_Algebraic_Sum_of_Binary_Numbers|Exercise 2.3: Algebraic Sum of Binary Numbers]] |

| − | [[Aufgaben: | + | [[Aufgaben:Exercise_2.4:_Number_Lottery_(6_from_49)|Exercise 2.4: Number Lottery (6 from 49)]] |

Latest revision as of 17:32, 7 February 2024

Contents

General description of the binomial distribution

$\text{Definition:}$ The »binomial distribution« represents an important special case for the occurrence probabilities of a discrete random variable.

To derive the binomial distribution, we assume that $I$ binary and statistically independent random variables $b_i$ each can achieve

- the value $1$ with probability ${\rm Pr}(b_i = 1) = p$, and

- the value $0$ with probability ${\rm Pr}(b_i = 0) = 1-p$.

Then the sum $z$ is also a discrete random variable with the symbol set $\{0, \ 1, \ 2,\hspace{0.1cm}\text{ ...} \hspace{0.1cm}, \ I\}$, which is called binomially distributed:

- $$z=\sum_{i=1}^{I}b_i.$$

Thus, the symbol set size is $M = I + 1.$

$\text{Example 1:}$ The binomial distribution finds manifold applications in Communications Engineering as well as in other disciplines:

- It describes the distribution of rejects in statistical quality control.

- It allows the calculation of the residual error probability in blockwise coding.

- The bit error rate of a digital transmission system obtained by simulation is actually a binomially distributed random quantity.

Probabilities of the binomial distribution

$\text{Calculation rule:}$ For the »probabilities of the binomial distribution« with $μ = 0, \hspace{0.1cm}\text{...} \hspace{0.1cm}, \ I$:

- $$p_\mu = {\rm Pr}(z=\mu)={I \choose \mu}\cdot p\hspace{0.05cm}^\mu\cdot ({\rm 1}-p)\hspace{0.05cm}^{I-\mu}.$$

The first term here indicates the number of combinations $($read: $I\ \text{ over }\ μ)$:

- $${I \choose \mu}=\frac{I !}{\mu !\cdot (I-\mu) !}=\frac{ {I\cdot (I- 1) \cdot \ \cdots \ \cdot (I-\mu+ 1)} }{ 1\cdot 2\cdot \ \cdots \ \cdot \mu}.$$

$\text{Additional notes:}$

- For very large values of $I$, the binomial distribution can be approximated by the »Poisson distribution« described in the next section.

- If at the same time the product $I · p \gg 1$, then according to »de Moivre–Laplace's $($central limit$)$ theorem«, the Poisson distribution $($and hence the binomial distribution$)$ transitions to a discrete »Gaussian distribution«.

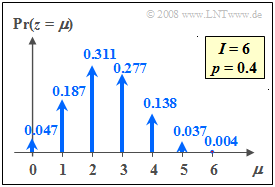

$\text{Example 2:}$ The graph shows the probabilities of the binomial distribution for $I =6$ and $p =0.4$.

- Thus $M = I+1=7$ probabilities are different from zero.

- In contrast, for $I = 6$ and $p = 0.5$, the probabilities of the binomial distribution are as follows:

- $$\begin{align*}{\rm Pr}(z\hspace{-0.05cm} =\hspace{-0.05cm}0) & = {\rm Pr}(z\hspace{-0.05cm} =\hspace{-0.05cm}6)\hspace{-0.05cm} =\hspace{-0.05cm} 1/64\hspace{-0.05cm} = \hspace{-0.05cm}0.015625 ,\\ {\rm Pr}(z\hspace{-0.05cm} =\hspace{-0.05cm}1) & = {\rm Pr}(z\hspace{-0.05cm} =\hspace{-0.05cm}5) \hspace{-0.05cm}= \hspace{-0.05cm}6/64 \hspace{-0.05cm}=\hspace{-0.05cm} 0.09375,\\ {\rm Pr}(z\hspace{-0.05cm} =\hspace{-0.05cm}2) & = {\rm Pr}(z\hspace{-0.05cm} =\hspace{-0.05cm}4)\hspace{-0.05cm} = \hspace{-0.05cm}15/64 \hspace{-0.05cm}= \hspace{-0.05cm}0.234375 ,\\ {\rm Pr}(z\hspace{-0.05cm} =\hspace{-0.05cm}3) & = 20/64 \hspace{-0.05cm}= \hspace{-0.05cm} 0.3125 .\end{align*}$$

- These are symmetrical with respect to the abscissa value $\mu = I/2 = 3$.

$\text{Example 3:}$ Another example of the application of the binomial distribution is the »calculation of the block error probability in Digital Signal Transmission«.

If one transmits blocks each of $I =10$ binary symbols over a channel

- with probability $p = 0.01$ that one symbol is falsified ⇒ random variable $e_i = 1$, and

- correspondingly with probability $1 - p = 0.99$ for an unfalsified symbol ⇒ random variable $e_i = 0$,

then the new random variable $f$ ⇒ »number of block errors« is:

- $$f=\sum_{i=1}^{I}e_i.$$

This random variable $f$ can take all integer values between $0$ $($no symbol is falsified$)$ and $I$ $($all symbols symbol are falsified$)$ .

- We denote the probabilities for $\mu$ falsifications by $p_μ$.

- The case where all $I$ symbols are correctly transmitted occurs with probability $p_0 = 0.99^{10} ≈ 0.9044$ .

- This also follows from the binomial formula for $μ = 0$ considering the definition $10\, \text{ over }\, 0 = 1$.

- A single symbol error $(f = 1)$ occurs with the probability $p_1 = \rm 10\cdot 0.01\cdot 0.99^9\approx 0.0914.$

- The first factor considers that there are exactly $10\, \text{ over }\, 1 = 10$ possibilities for the position of a single error.

- The other two factors take into account that one symbol must be falsified and nine must be transmitted correctly if $f =1$ is to hold.

For $f =2$ there are clearly more combinations, namely $10\, \text{ over }\, 2 = 45$, and we get

- $$p_2 = \rm 45\cdot 0.01^2\cdot 0.99^8\approx 0.0041.$$

If a block code can correct up to two errors, the »block error probability« is

- $$p_{\rm block} = \it p_{\rm 3} \rm +\hspace{0.1cm}\text{ ...} \hspace{0.1cm} \rm + \it p_{\rm 10}\approx \rm 10^{-4},$$

or

- $$p_{\rm block} = \rm 1-\it p_{\rm 0}-\it p_{\rm 1}-p_{\rm 2}\approx \rm 10^{-4}.$$

- One can see that for large $I$ values the second possibility of calculation via the complement leads faster to the goal.

- However, one could also consider that for these numerical values $p_{\rm block} ≈ p_3$ holds as an approximation.

⇒ Use the interactive HTML5/JS applet »Binomial and Poisson distribution« to find the binomial probabilities for any $I$ and $p$ .

Moments of the binomial distribution

You can calculate the moments in general using the equations in the chapters

$\text{Calculation rules:} $ For the »$k$-th order moment« of a binomially distributed random variable, the general rule is:

- $$m_k={\rm E}\big[z^k\big]=\sum_{\mu={\rm 0} }^{I}\mu^k\cdot{I \choose \mu}\cdot p\hspace{0.05cm}^\mu\cdot ({\rm 1}-p)\hspace{0.05cm}^{I-\mu}.$$

From this, we obtain for after some transformations

- the first order moment ⇒ »linear mean«:

- $$m_1 ={\rm E}\big[z\big]= I\cdot p,$$

- the second order moment ⇒ »power«:

- $$m_2 ={\rm E}\big[z^2\big]= (I^2-I)\cdot p^2+I\cdot p,$$

- the variance by applying »Steiner's theorem»:

- $$\sigma^2 = {m_2-m_1^2} = {I \cdot p\cdot (1-p)} ,$$

- the standard deviation:

- $$\sigma = \sqrt{I \cdot p\cdot (1-p)}.$$

The maximum variance $σ^2 = I/4$ is obtained for the »characteristic probability« $p = 1/2$.

- In this case, the binomial probabilities are symmetric around the mean $m_1 = I/2 \ ⇒ \ p_μ = p_{I–μ}$.

- The more the characteristic probability $p$ deviates from the value $1/2$ ,

- the smaller is the standard deviation $σ$, and

- the more asymmetric become the probabilities around the mean $m_1 = I · p$.

$\text{Example 4:}$

As in $\text{Example 3}$, we consider a block of $I =10$ binary symbols, each of which is independently falsified with probability $p = 0.01$ . Then holds:

- The mean number of block errors is equal to $m_f = {\rm E}\big[ f\big] = I · p = 0.1$.

- The standard deviation of the random variable $f$ is $σ_f = \sqrt{0.1 \cdot 0.99}≈ 0.315$.

In contrast, in the completely falsified channel ⇒ bit error probability $p = 1/2$ results in the values

- $m_f = 5$ ⇒ on average, five of the ten bits within a block are wrong,

- $σ_f = \sqrt{I}/2 ≈1.581$ ⇒ maximum standard deviation.

Exercises for the chapter

Exercise 2.3: Algebraic Sum of Binary Numbers

Exercise 2.4: Number Lottery (6 from 49)