Difference between revisions of "Signal Representation/Calculating with Complex Numbers"

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

With the introduction of the irrational numbers the solution of the equation $a^2-2=0$ was possible, but not the solution of the equation $a^2+1=0$. | With the introduction of the irrational numbers the solution of the equation $a^2-2=0$ was possible, but not the solution of the equation $a^2+1=0$. | ||

| − | The mathematician [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leonhard_Euler Leonhard Euler] solved this problem by extending the set of real numbers by the | + | The mathematician [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leonhard_Euler Leonhard Euler] solved this problem by extending the set of real numbers by the "imaginary numbers" . He defined the '''imaginary unit''' as follows: |

:$${\rm j}=\sqrt{-1} \ \Rightarrow \ {\rm j}^{2}=-1.$$ | :$${\rm j}=\sqrt{-1} \ \Rightarrow \ {\rm j}^{2}=-1.$$ | ||

| − | It should be noted that Euler called this quantity „$\rm i$” and this is still common in mathematics today. In electrical engineering, on the other hand, the designation | + | It should be noted that Euler called this quantity „$\rm i$” and this is still common in mathematics today. In electrical engineering, on the other hand, the designation "$\rm j$" has become generally accepted since "$\rm i$" is already occupied by the time-dependent current. |

{{BlaueBox|TEXT= | {{BlaueBox|TEXT= | ||

$\text{Definition:}$ | $\text{Definition:}$ | ||

| − | The | + | The $\text{complex number}$ $z$ is generally the sum of a real number $x$ and an imaginary number ${\rm j} \cdot y$: |

:$$z=x+{\rm j}\cdot y.$$ | :$$z=x+{\rm j}\cdot y.$$ | ||

| − | $x$ and $y$ are derived from the quantity $\mathbb{R}$ from the real numbers. The set of all possible complex numbers is called the body $\mathbb{C}$ of the complex numbers.}} | + | *$x$ and $y$ are derived from the quantity $\mathbb{R}$ from the real numbers. |

| + | *The set of all possible complex numbers is called the body $\mathbb{C}$ of the complex numbers.}} | ||

| − | The number line of real numbers now becomes the complex plane, which is spanned by two number | + | The number line of real numbers now becomes the complex plane, which is spanned by two number lines twisted by $90^\circ$ for real part and imaginary part. |

[[File:P_ID823_Sig_T_1_3_S2_neu.png|right|frame|Numbers in the complex plane]] | [[File:P_ID823_Sig_T_1_3_S2_neu.png|right|frame|Numbers in the complex plane]] | ||

{{GraueBox|TEXT= | {{GraueBox|TEXT= | ||

| − | $\text{ | + | $\text{Example 1:}$ |

The complex number $z_1 = 2 \cdot {\rm j}$ is one of two possible solutions of the equation $z^2+4=0$. The other solution is $z_2 = -2 \cdot {\rm j}$. | The complex number $z_1 = 2 \cdot {\rm j}$ is one of two possible solutions of the equation $z^2+4=0$. The other solution is $z_2 = -2 \cdot {\rm j}$. | ||

| Line 66: | Line 67: | ||

:$$(z-2- {\rm j})(z-2+ {\rm j}) = 0 \; \ \Rightarrow \;\ z^{2}-4 \cdot z+5=0.$$ | :$$(z-2- {\rm j})(z-2+ {\rm j}) = 0 \; \ \Rightarrow \;\ z^{2}-4 \cdot z+5=0.$$ | ||

| − | $z_4 = z_3^\ast$ is also called the | + | $z_4 = z_3^\ast$ is also called the $\text{complex conjugate}$ of $z_3$. |

*The sum $z_3 + z_4$ is real: | *The sum $z_3 + z_4$ is real: | ||

| Line 76: | Line 77: | ||

| − | ''Note'': In the literature, complex quantities are often marked by underlining. This is not used in the $\rm LNTwww$ | + | ''Note'': In the literature, complex quantities are often marked by underlining. This is not used in the $\rm LNTwww$ books. |

| Line 90: | Line 91: | ||

:$$x = |z| \cdot \cos(\phi), \hspace{0.6cm} y = |z| \cdot \sin(\phi ).$$ | :$$x = |z| \cdot \cos(\phi), \hspace{0.6cm} y = |z| \cdot \sin(\phi ).$$ | ||

| − | Thus the complex | + | Thus the complex quantity $z$ can also be displayed in the following form: |

:$$z = |z| \cdot \cos (\phi) + {\rm j} \cdot |z| \cdot \sin (\phi) = |z| \cdot {\rm e}^{{\rm j} \hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm} \phi}.$$ | :$$z = |z| \cdot \cos (\phi) + {\rm j} \cdot |z| \cdot \sin (\phi) = |z| \cdot {\rm e}^{{\rm j} \hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm} \phi}.$$ | ||

| − | The | + | The $\text{Euler's theorem}$ was used, which is proved below. This states that the complex quantity $ {\rm e}^{{\rm j} \hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm} \phi}$ exhibits the real part $\cos(\phi)$ and the imaginary part $\sin(\phi)$ . |

| − | Further one recognizes from the diagram that for the | + | Further one recognizes from the diagram that for the "complex conjugates" of $z = x + {\rm j}\cdot y$ applies: |

:$$z^{\star} = x - {\rm j} \cdot y = |z| \cdot {\rm e}^{-{\rm j}\hspace{0.05cm} \cdot \hspace{0.05cm}\phi}.$$ | :$$z^{\star} = x - {\rm j} \cdot y = |z| \cdot {\rm e}^{-{\rm j}\hspace{0.05cm} \cdot \hspace{0.05cm}\phi}.$$ | ||

| Line 126: | Line 127: | ||

\sin(x).$$ | \sin(x).$$ | ||

| − | *From this the | + | *From this the $\text{Euler Theorem}$ follows directly: |

:$${\rm e}^{ {\rm j}\hspace{0.03cm} \cdot \hspace{0.03cm}x} = \cos (x) + {\rm j} \cdot \sin (x) \hspace{2cm} | :$${\rm e}^{ {\rm j}\hspace{0.03cm} \cdot \hspace{0.03cm}x} = \cos (x) + {\rm j} \cdot \sin (x) \hspace{2cm} | ||

| Line 141: | Line 142: | ||

\hspace {0.05cm} \phi_2}$$ | \hspace {0.05cm} \phi_2}$$ | ||

| − | are defined in such a way, that for the special case of a vanishing imaginary part, the rules of calculation of real numbers are given. This is called the so called | + | are defined in such a way, that for the special case of a vanishing imaginary part, the rules of calculation of real numbers are given. This is called the so called "principle of permanence". |

The following rules apply to the basic arithmetic operations: | The following rules apply to the basic arithmetic operations: | ||

| − | *The sum of two complex numbers (resp. their difference) is made by adding their real and imaginary parts (resp. subtracting): | + | *The sum of two complex numbers (resp. their difference) is made by adding their real and imaginary parts (resp. subtracting): |

::<math>z_3 = z_1 + z_2 = (x_1+x_2) + {\rm j}\cdot (y_1 + y_2),</math> | ::<math>z_3 = z_1 + z_2 = (x_1+x_2) + {\rm j}\cdot (y_1 + y_2),</math> | ||

| Line 150: | Line 151: | ||

::<math>z_4 = z_1 - z_2 = (x_1-x_2) + {\rm j}\cdot (y_1 - y_2).</math> | ::<math>z_4 = z_1 - z_2 = (x_1-x_2) + {\rm j}\cdot (y_1 - y_2).</math> | ||

| − | *The product of two complex numbers can be formed in the real part and imaginary part description by multiplication considering <math>{\rm j}^{2}=-1</math> | + | *The product of two complex numbers can be formed in the real part and imaginary part description by multiplication considering <math>{\rm j}^{2}=-1</math>. However, multiplication is simpler if <math>z_1</math> and <math>z_2</math> are written with absolute value and phase: |

::<math>z_5 = z_1 \cdot z_2 = (x_1\cdot x_2 - y_1\cdot y_2) + {\rm j}\cdot (x_1\cdot y_2 + x_2\cdot y_1),</math> | ::<math>z_5 = z_1 \cdot z_2 = (x_1\cdot x_2 - y_1\cdot y_2) + {\rm j}\cdot (x_1\cdot y_2 + x_2\cdot y_1),</math> | ||

| Line 162: | Line 163: | ||

\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} |z_5| = |z_1| \cdot |z_2| , \hspace{0.3cm}\phi_5 = \phi_1 + \phi_2 .</math> | \Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} |z_5| = |z_1| \cdot |z_2| , \hspace{0.3cm}\phi_5 = \phi_1 + \phi_2 .</math> | ||

| − | *The division is also more manageable in the exponential notation. The two amounts are divided and the phases are subtracted in the exponent: | + | *The division is also more manageable in the exponential notation. The two amounts are divided and the phases are subtracted in the exponent: |

::<math>z_6 = \frac{z_1}{z_2} = |z_6| \cdot {\rm e}^{{\rm j} \hspace {0.05cm}\cdot | ::<math>z_6 = \frac{z_1}{z_2} = |z_6| \cdot {\rm e}^{{\rm j} \hspace {0.05cm}\cdot | ||

| Line 174: | Line 175: | ||

In the graphic are shown as points within the complex plane: | In the graphic are shown as points within the complex plane: | ||

| − | + | #the complex number <math>z=0.75 + {\rm j} = 1.25 \cdot {\rm e}^{\hspace{0.03cm}{\rm j}\hspace{0.03cm} \cdot \hspace{0.05cm}53.1^{\circ} }</math>, | |

| + | #its complex conjugate <math>z^{\ast} = 0.75 - {\rm j} = 1.25 \cdot {\rm e}^{ - {\rm j} \hspace{0.03cm}\cdot \hspace{0.03cm}53.1^{\circ} }</math>, | ||

| + | #the sum <math>s=z+z^{\ast}=1.5</math> (purely real), | ||

| + | #the difference <math>d=z-z^{\ast}=2 \cdot {\rm j}</math> (purely imaginary), | ||

| + | #the product <math>p=z \cdot z^{\ast} = 1.25^{2} \approx 1.5625</math> (purely real), | ||

| + | #the division <math>q= {z}/{z^{\ast} }={\rm e}^{\hspace{0.05cm} {\rm j} \hspace{0.03cm}\cdot \hspace{0.03cm}106.2^{\circ} }</math> with amplitude $1$ and the double phase angle of $z$.}} | ||

| − | + | The following (German language) learning video summarizes the topic of this chapter in a compact way:<br> [[Rechnen_mit_komplexen_Zahlen_(Lernvideo)|Rechnen mit komplexen Zahlen]] ⇒ "Arithmetic operations involving complex numbers". | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| Line 198: | Line 189: | ||

==Exercises for the chapter== | ==Exercises for the chapter== | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | [[Aufgaben:Exercise_1.3:_Calculating_With_Complex_Numbers|Exercise 1.3: Calculating | + | [[Aufgaben:Exercise_1.3:_Calculating_With_Complex_Numbers|Exercise 1.3: Calculating with Complex Numbers]] |

[[Aufgaben:Exercise_1.3Z:_Calculating_with_Complex_Numbers_II|Exercise 1.3Z: Calculating with Complex Numbers II]] | [[Aufgaben:Exercise_1.3Z:_Calculating_with_Complex_Numbers_II|Exercise 1.3Z: Calculating with Complex Numbers II]] | ||

{{Display}} | {{Display}} | ||

Revision as of 15:33, 9 April 2021

Contents

The Set of Real Numbers

In the following chapters of this book, complex quantities always play an important role. Although calculating with complex numbers is already treated and practiced in school mathematics, our experience has shown that even students of natural sciences and technical subjects have problems with it. Perhaps these difficulties are also related to the fact that "complex" is often used as a synonym for "complicated" in everyday life, while "real" stands for "reliable, honest and truthful" according to the Duden dictionary.

Therefore, the calculation rules for complex numbers are briefly summarized here at the end of this first basic chapter.

First there are some remarks about real quantities of numbers, for which in the strict mathematical sense the term "number field" would be more correct. These include:

$\text{Definitions:}$

- $\text{Natural Numbers}$ $\mathbb{N} = \{1, 2, 3, \text{...}\hspace{0.05cm} \}$. Using these numbers, for $n, \ k \in \mathbb{N}$ the arithmetic operations "addition" $(m = n +k)$, "multiplication" $(m = n \cdot k)$ and "power formation" $(m = n^k)$ are possible. The respective result of a calculation is again a natural number: $m \in \mathbb{N}$.

- $\text{Integer Numbers}$ $\mathbb{Z} = \{\text{...}\hspace{0.05cm} , -3, -2, -1, \ 0, +1, +2, +3, \text{...}\hspace{0.05cm}\}$. This set of numbers is an extension of the natural numbers $\mathbb{N}$. The introduction of the set $\mathbb{Z}$ was necessary to capture the result set of a subtraction $(m = n -k$, for example $5 - 7 = - 2)$.

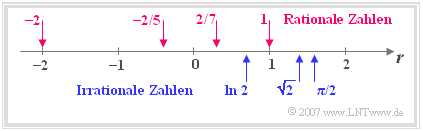

- $\text{Rational Numbers}$ $\mathbb{Q} = \{z/n\}$ with $z \in \mathbb{Z}$ and $n \in \mathbb{N}$. With this set of numbers, also known as fractions, there is a defined result for each division. If you write a rational number in decimal notation, only zeros appear after a certain decimal place $($Example: $-2/5 = -0.400\text{...}\hspace{0.05cm})$ or periodicities $($Example: $2/7 = 0.285714285\text{...}\hspace{0.05cm})$. Since $n = 1$ is allowed, the integers are a subset of the rational numbers: $\mathbb{Z} \subset \mathbb{Q}$.

- $\text{Irrational Numbers}$ $\mathbb{I} \neq {z/n}$ mit $z \in \mathbb{Z}$, $n \in \mathbb{N}$. Although there are infinite rational numbers, there are still infinite numbers which cannot be represented as a fraction. Examples are the number $\pi = 3.141592654\text{...}\hspace{0.05cm}$ (where there are no periods even with more decimal places) or the result of the equation $a^{2}=2 \,\,\Rightarrow \;\;a=\pm \sqrt{2}=\pm1.414213562\text{...}\hspace{0.05cm}$. This result is also irrational, which has already been proved by Euclid in antiquity.

- $\text{Real Numbers}$ $\mathbb{R} = \mathbb{Q} \cup \mathbb{I}$ as the sum of all rational and irrational numbers.

- These can be ordered according to their numerical values and can be drawn on the so called "number line" as shown in the adjacent graph.

Imaginary and Complex Numbers

With the introduction of the irrational numbers the solution of the equation $a^2-2=0$ was possible, but not the solution of the equation $a^2+1=0$.

The mathematician Leonhard Euler solved this problem by extending the set of real numbers by the "imaginary numbers" . He defined the imaginary unit as follows:

- $${\rm j}=\sqrt{-1} \ \Rightarrow \ {\rm j}^{2}=-1.$$

It should be noted that Euler called this quantity „$\rm i$” and this is still common in mathematics today. In electrical engineering, on the other hand, the designation "$\rm j$" has become generally accepted since "$\rm i$" is already occupied by the time-dependent current.

$\text{Definition:}$ The $\text{complex number}$ $z$ is generally the sum of a real number $x$ and an imaginary number ${\rm j} \cdot y$:

- $$z=x+{\rm j}\cdot y.$$

- $x$ and $y$ are derived from the quantity $\mathbb{R}$ from the real numbers.

- The set of all possible complex numbers is called the body $\mathbb{C}$ of the complex numbers.

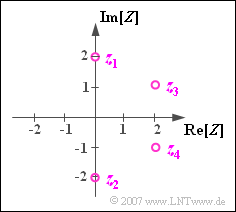

The number line of real numbers now becomes the complex plane, which is spanned by two number lines twisted by $90^\circ$ for real part and imaginary part.

$\text{Example 1:}$ The complex number $z_1 = 2 \cdot {\rm j}$ is one of two possible solutions of the equation $z^2+4=0$. The other solution is $z_2 = -2 \cdot {\rm j}$.

In contrast $z_3 = 2 + {\rm j}$ and $z_4 = 2 -{\rm j}$ give the two solutions to the following equation:

- $$(z-2- {\rm j})(z-2+ {\rm j}) = 0 \; \ \Rightarrow \;\ z^{2}-4 \cdot z+5=0.$$

$z_4 = z_3^\ast$ is also called the $\text{complex conjugate}$ of $z_3$.

- The sum $z_3 + z_4$ is real:

- $$z_3 + z_4 = 2 \cdot {\rm Re}[z_3]=2 \cdot {\rm Re}[z_4].$$

- The difference $z_3 - z_4$ is purely imaginary:

- $$z_3 - z_4 = {\rm j} \cdot \big [2 \cdot {\rm Im}[z_3] \big ] ={\rm j} \cdot \big [-2 \cdot {\rm Im}[z_4] \big ].$$

Note: In the literature, complex quantities are often marked by underlining. This is not used in the $\rm LNTwww$ books.

Representation by Amplidute and Phase

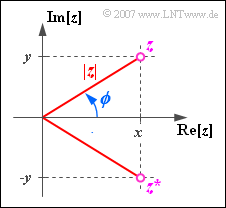

A complex number $z$ can be described not only by the real part $x$ and the imaginary part $y$ but also by its amplitude $|z|$ and the phase $\phi$ .

The following conversions apply:

- $$\left | z \right | = \sqrt{x^{2}+y^{2}}, \hspace{0.6cm}\phi = \arctan ({y}/{x}),$$

- $$x = |z| \cdot \cos(\phi), \hspace{0.6cm} y = |z| \cdot \sin(\phi ).$$

Thus the complex quantity $z$ can also be displayed in the following form:

- $$z = |z| \cdot \cos (\phi) + {\rm j} \cdot |z| \cdot \sin (\phi) = |z| \cdot {\rm e}^{{\rm j} \hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm} \phi}.$$

The $\text{Euler's theorem}$ was used, which is proved below. This states that the complex quantity $ {\rm e}^{{\rm j} \hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm} \phi}$ exhibits the real part $\cos(\phi)$ and the imaginary part $\sin(\phi)$ .

Further one recognizes from the diagram that for the "complex conjugates" of $z = x + {\rm j}\cdot y$ applies:

- $$z^{\star} = x - {\rm j} \cdot y = |z| \cdot {\rm e}^{-{\rm j}\hspace{0.05cm} \cdot \hspace{0.05cm}\phi}.$$

$\text{Proof of the Euler theorem:}$ This is based on the comparison of power series developments.

- The series development of the exponential function is:

- $${\rm e}^{x} = 1 + \frac{x}{1!}+ \frac{x^2}{2!}+ \frac{x^3}{3!} + \frac{x^4}{4!} +\text{ ...} \hspace{0.15cm}.$$

- With an imaginary argument you can also write:

- $${\rm e}^{ {\rm j}\hspace{0.03cm} \cdot \hspace{0.03cm}x} = 1 + {\rm j} \cdot \frac{x}{1!}+ {\rm j}^2 \cdot \frac{x^2}{2!}+ {\rm j}^3 \cdot \frac{x^3}{3!} + {\rm j}^4 \cdot \frac{x^4}{4!} + \text{ ...} \hspace{0.15cm}.$$

- Considering \({\rm j}^{2}=-1, \ \ {\rm j}^{3} = -{\rm j},\ \ {\rm j}^{4} = 1, \ \ {\rm j}^{5} = {\rm j}, \text{ ...} \hspace{0.15cm}\) and combining the real and the imaginary terms, one obtains

- $${\rm e}^{ {\rm j}\hspace{0.03cm} \cdot \hspace{0.03cm}x} = A(x) + {\rm j}\cdot B(x).$$

- The following applies to both series:

- $$A(x) = 1 - \frac{x^2}{2!} + \frac{x^4}{4!} - \frac{x^6}{6!}+ \text{ ...} \hspace{0.1cm}= \cos(x),\hspace{0.5cm} B(x) = \frac{x}{1!}- \frac{x^3}{3!} + \frac{x^5}{5!} - \frac{x^7}{7!}+ \text{ ...}= \sin(x).$$

- From this the $\text{Euler Theorem}$ follows directly:

- $${\rm e}^{ {\rm j}\hspace{0.03cm} \cdot \hspace{0.03cm}x} = \cos (x) + {\rm j} \cdot \sin (x) \hspace{2cm} \rm q.e.d.$$

Calculation Laws for Complex Numbers

The laws of arithmetic for two complex numbers

- $$z_1 = x_1 + {\rm j} \cdot y_1 = |z_1| \cdot {\rm e}^{{\rm j}\hspace {0.05cm}\cdot \hspace {0.05cm} \phi_1}, \hspace{0.5cm} z_2 = x_2 + {\rm j} \cdot y_2 = |z_2| \cdot {\rm e}^{{\rm j} \hspace {0.05cm}\cdot \hspace {0.05cm} \phi_2}$$

are defined in such a way, that for the special case of a vanishing imaginary part, the rules of calculation of real numbers are given. This is called the so called "principle of permanence".

The following rules apply to the basic arithmetic operations:

- The sum of two complex numbers (resp. their difference) is made by adding their real and imaginary parts (resp. subtracting):

- \[z_3 = z_1 + z_2 = (x_1+x_2) + {\rm j}\cdot (y_1 + y_2),\]

- \[z_4 = z_1 - z_2 = (x_1-x_2) + {\rm j}\cdot (y_1 - y_2).\]

- The product of two complex numbers can be formed in the real part and imaginary part description by multiplication considering \({\rm j}^{2}=-1\). However, multiplication is simpler if \(z_1\) and \(z_2\) are written with absolute value and phase:

- \[z_5 = z_1 \cdot z_2 = (x_1\cdot x_2 - y_1\cdot y_2) + {\rm j}\cdot (x_1\cdot y_2 + x_2\cdot y_1),\]

- \[z_5 = |z_1| \cdot {\rm e}^{{\rm j} \hspace {0.05cm}\cdot \hspace {0.05cm} \phi_1} \cdot |z_2| \cdot {\rm e}^{{\rm j}\hspace {0.05cm}\cdot \hspace {0.05cm} \phi_2}= |z_5| \cdot {\rm e}^{{\rm j} \hspace {0.05cm}\cdot \hspace {0.05cm} \phi_5} \hspace{0.3cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} |z_5| = |z_1| \cdot |z_2| , \hspace{0.3cm}\phi_5 = \phi_1 + \phi_2 .\]

- The division is also more manageable in the exponential notation. The two amounts are divided and the phases are subtracted in the exponent:

- \[z_6 = \frac{z_1}{z_2} = |z_6| \cdot {\rm e}^{{\rm j} \hspace {0.05cm}\cdot \hspace {0.05cm} \phi_6} \hspace{0.3cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} |z_6| = \frac{|z_1|}{|z_2|}, \hspace{0.3cm}\phi_6 = \phi_1 - \phi_2 .\]

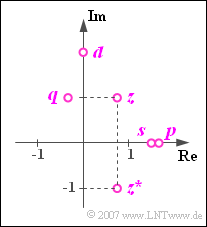

$\text{Beispiel 2:}$ In the graphic are shown as points within the complex plane:

- the complex number \(z=0.75 + {\rm j} = 1.25 \cdot {\rm e}^{\hspace{0.03cm}{\rm j}\hspace{0.03cm} \cdot \hspace{0.05cm}53.1^{\circ} }\),

- its complex conjugate \(z^{\ast} = 0.75 - {\rm j} = 1.25 \cdot {\rm e}^{ - {\rm j} \hspace{0.03cm}\cdot \hspace{0.03cm}53.1^{\circ} }\),

- the sum \(s=z+z^{\ast}=1.5\) (purely real),

- the difference \(d=z-z^{\ast}=2 \cdot {\rm j}\) (purely imaginary),

- the product \(p=z \cdot z^{\ast} = 1.25^{2} \approx 1.5625\) (purely real),

- the division \(q= {z}/{z^{\ast} }={\rm e}^{\hspace{0.05cm} {\rm j} \hspace{0.03cm}\cdot \hspace{0.03cm}106.2^{\circ} }\) with amplitude $1$ and the double phase angle of $z$.

The following (German language) learning video summarizes the topic of this chapter in a compact way:

Rechnen mit komplexen Zahlen ⇒ "Arithmetic operations involving complex numbers".

Exercises for the chapter

Exercise 1.3: Calculating with Complex Numbers

Exercise 1.3Z: Calculating with Complex Numbers II