Contents

- 1 # OVERVIEW OF THE FOURTH MAIN CHAPTER #

- 2 Properties and examples

- 3 Joint PDF

- 4 Two-dimensional CDF

- 5 PDF and CDF for statistically independent components

- 6 PDF and CDF for statistically dependent components

- 7 Expected values of two-dimensional random variables

- 8 Correlation coefficient

- 9 Korrelationsgerade

- 10 Aufgaben zum Kapitel

# OVERVIEW OF THE FOURTH MAIN CHAPTER #

Now random variables with statistical bindings are treated and illustrated by typical examples. After the general description of two-dimensional random variables, we turn to the autocorrelation function (ACF), the cross correlation function (CCF) and the associated spectral functions (PSD, CPSD) .

Specifically, it covers:

- the statistical description of 2D random variables using the (joint) PDF,

- the difference between statistical dependence and correlation, ???

- the classification features stationarity and ergodicity of stochastic processes,

- the definitions of autocorrelation function (ACF) and power spectral density (PSD),

- the definitions of cross correlation function and cross power spectral density, and

- the numerical determination of all these quantities in the two- and multi-dimensional cases.

For more information on Two-Dimensional Random Variables, as well as tasks, simulations, and programming exercises, see

- Chapter 5: Two-dimensional random variables (program "zwd")

- Chapter 9: Stochastic Processes (program "sto")

of the practical course "Simulation Methods in Communications Engineering". This (former) LNT course at the TU Munich is based on

- the teaching software package LNTsim ⇒ Link refers to the German ZIP–version of the program,

- Internship Guide – Part A ⇒ Link refers to the German PDF–version with chapter 5: pages 81-97,

- the Internship Guide – Part B ⇒ Link refers to the German PDF–version with chapter 9: pages 207-228.

Properties and examples

As a transition to the correlation functions we now consider two random variables $x$ and $y$, between which statistical bindings(???) exist. Each of the two random variables can be described on its own with the introduced characteristic quantities

- corresponding to the second main chapter ⇒ Discrete Random Variables

- but the third main chapter ⇒ Continuous Random Variables.

$\text{Definition:}$ To describe the correlations between two variables $x$ and $y$ it is convenient to combine the two components into one two-dimensional random variable $(x, y)$ }.

- The individual components can be signals such as the real– and imaginary parts of a phase modulated signal.

- But there are a variety of 2D–random variables in other domains as well, as the following example will show

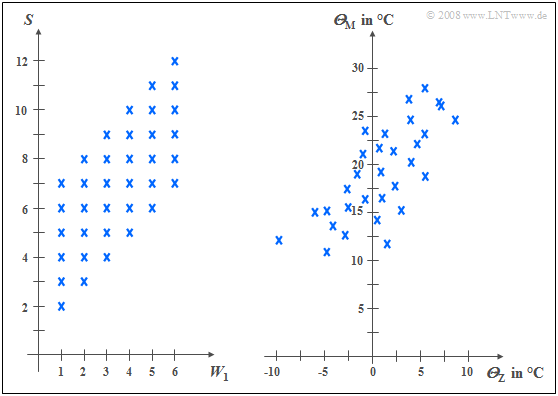

$\text{Example 1:}$ The left diagram is from the random experiment "Throwing two dice". Plotted to the right is the number of the first die $(W_1)$, plotted to the top is the sum $S$ of both dice. The two components here are each discrete random variables between which there are statistical dependencies(???):

- If $W_1 = 1$, then $S$ can only take values between $2$ and $7$ and each with equal probability.

- In contrast, for $W_1 = 6$ all values between $7$ and $12$ are possible, also with equal probability.

In the right graph, the maximum temperatures of the $31$ days in May 2002 of Munich (to the top) and the Zugspitze (to the right) are contrasted. Both random variables are continuous in value:

- although the measurement points are about $\text{100 km}$ apart, and on the Zugspitze, due to the different altitudes $($nearly $3000$ versus $520$ meters$)$ is on average about $20$ degrees colder than in Munich, one recognizes nevertheless a certain statistical dependence between the two random variables ${\it Θ}_{\rm M}$ and ${\it Θ}_{\rm Z}$.

- If it is warm in Munich, then pleasant temperatures are also more likely to be expected on the Zugspitze. However, the relationship is not deterministic: The coldest day in May 2002 was a different day in Munich than the coldest day on the Zugspitze.

Joint PDF

We restrict ourselves here mostly to continuous random variables. However, sometimes the peculiarities of two-dimensional discrete random variables are discussed in more detail. Most of the characteristics previously defined for one-dimensional random variables can be easily extended to two-dimensional variables.

$\text{Definition:}$ The probability density function of the two-dimensional random variable at the location $(x_\mu, y_\mu)$ ⇒ joint PDF is an extension of the one-dimensional PDF $(∩$ denotes logical AND operation$)$:

- $$f_{xy}(x_\mu, \hspace{0.1cm}y_\mu) = \lim_{\left.{\delta x\rightarrow 0 \atop {\delta y\rightarrow 0} }\right. }\frac{ {\rm Pr}\big [ (x_\mu - {\rm \Delta} x/{\rm 2} \le x \le x_\mu + {\rm \Delta} x/{\rm 2}) \cap (y_\mu - {\rm \Delta} y/{\rm 2} \le y \le y_\mu +{\rm \Delta}y/{\rm 2}) \big] }{ {\rm \delta} \ x\cdot{\rm \Delta} y}.$$

$\rm Note$:

- If the 2D–random variable is discrete, the definition must be slightly modified:

- For the lower range limits in each case, the "≤" sign must then be replaced by the "<" sign according to the page CDF for discrete random variables

.

Using this (joint) WDF $f_{xy}(x, y)$ statistical dependencies within the two-dimensional random variable $(x, y)$ are also fully captured in contrast to the two one-dimensional density functions ⇒ marginal probability density functions:

- $$f_{x}(x) = \int _{-\infty}^{+\infty} f_{xy}(x,y) \,\,{\rm d}y ,$$

- $$f_{y}(y) = \int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} f_{xy}(x,y) \,\,{\rm d}x .$$

These two marginal density functions $f_x(x)$ and $f_y(y)$

- provide only statistical information about the individual components $x$ and $y$, respectively,

- but not about the bindings between them.

Two-dimensional CDF

$\text{Definition:}$ The 2D distribution function like the 2D WDF, is merely a useful extension of the one-dimensional distribution function (CDF):

- $$F_{xy}(r_{x},r_{y}) = {\rm Pr}\big [(x \le r_{x}) \cap (y \le r_{y}) \big ] .$$

The following similarities and differences between the 1D CDF and the 2D CDF emerge:

- The functional relationship between two-dimensional PDF and two-dimensional VTF is given by integration as in the one-dimensional case, but now in two dimensions. For continuous random variables:

- $$F_{xy}(r_{x},r_{y})=\int_{-\infty}^{r_{y}} \int_{-\infty}^{r_{x}} f_{xy}(x,y) \,\,{\rm d}x \,\, {\rm d}y .$$

- Inversely, the probability density function can be given from the distribution function by partial differentiation to $r_{x}$ and $r_{y}$ :

- $$f_{xy}(x,y)=\frac{{\rm d}^{\rm 2} F_{xy}(r_{x},r_{y})}{{\rm d} r_{x} \,\, {\rm d} r_{y}}\Bigg|_{\left.{r_{x}=x \atop {r_{y}=y}}\right.}.$$

- Relative to the distribution function $F_{xy}(r_{x}, r_{y})$ the following limits apply:

- $$F_{xy}(-\infty,-\infty) = 0,$$

- $$F_{xy}(r_{\rm x},+\infty)=F_{x}(r_{x} ),$$

- $$F_{xy}(+\infty,r_{y})=F_{y}(r_{y} ) ,$$

- $$F_{xy} (+\infty,+\infty) = 1.$$

- In the limiting case $($infinitely large $r_{x}$ and $r_{y})$ Thus, for the 2D VTF, the value $1$. From this, we obtain the normalization condition for the 2D WDF:

- $$\int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} \int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} f_{xy}(x,y) \,\,{\rm d}x \,\,{\rm d}y=1 . $$

$\text{Conclusion:}$ Note the significant difference between one-dimensional and two-dimensional random variables:

- For one-dimensional random variables, the area under the PDF always yields the value $1$.

- For two-dimensional random variables, the PDF volume is always equal $1$.

PDF and CDF for statistically independent components

For statistically independent components $x$ and $y$ the following holds for the joint probability according to the elementary laws of statistics if $x$ and $y$ are continuous in value:

- $${\rm Pr} \big[(x_{\rm 1}\le x \le x_{\rm 2}) \cap( y_{\rm 1}\le y\le y_{\rm 2})\big] ={\rm Pr} (x_{\rm 1}\le x \le x_{\rm 2}) \cdot {\rm Pr}(y_{\rm 1}\le y\le y_{\rm 2}) .$$

For this, independent components can also be written:

- $${\rm Pr} \big[(x_{\rm 1}\le x \le x_{\rm 2}) \cap(y_{\rm 1}\le y\le y_{\rm 2})\big] =\int _{x_{\rm 1}}^{x_{\rm 2}}f_{x}(x) \,{\rm d}x\cdot \int_{y_{\rm 1}}^{y_{\rm 2}} f_{y}(y) \, {\rm d}y.$$

$\text{Definition:}$ It follows that for statistical independence the following condition must be satisfied with respect to the 2D–probability density function:

- $$f_{xy}(x,y)=f_{x}(x) \cdot f_y(y) .$$

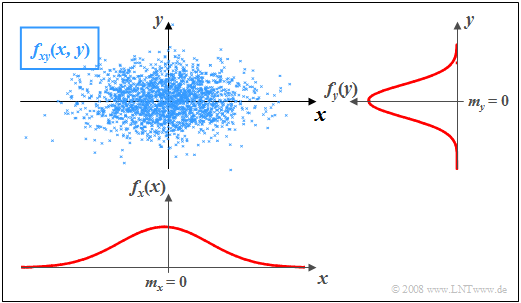

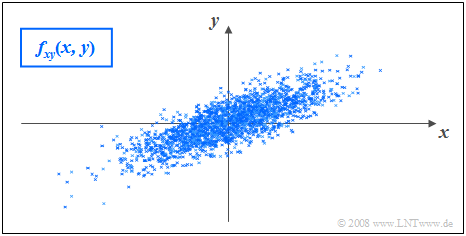

$\text{Example 2:}$ In the graph, the instantaneous values of a two-dimensional random variable are plotted as points in the $(x, y)$–plane.

- Ranges with many points, which accordingly appear dark, indicate large values of the 2D–WDF $f_{xy}(x, y)$.

- In contrast, the random variable $(x, y)$ has relatively few components in rather bright areas.

The graph can be interpreted as follows:

- The marginal probability densities $f_{x}(x)$ and $f_{y}(y)$ already indicate that both $x$ and $y$ are Gaussian and zero mean, and that the random variable $x$ has a larger standard deviation than $y$ .

- $f_{x}(x)$ and $f_{y}(y)$ however, do not provide information on whether or not statistical bindings exist for the random variable $(x, y)$ .

- However, using the 2D WDF $f_{xy}(x,y)$ one can see that there are no statistical bindings between the two components $x$ and $y$ here.

- With statistical independence, any cut through $f_{xy}(x, y)$ parallel to $y$-axis yields a function that is equal in shape to the edge–WDF $f_{y}(y)$. Similarly, all cuts parallel to $x$-axis are equal in shape to $f_{x}(x)$.

- This fact is equivalent to saying that in this example $f_{xy}(x, y)$ can be represented as the product of the two marginal probability densities: $f_{xy}(x,y)=f_{x}(x) \cdot f_y(y) .$

PDF and CDF for statistically dependent components

If there are statistical bindings between $x$ and $y$, then different cuts parallel to $x$– and $y$–axis, respectively, yield different, non-shape equivalent functions. In this case, of course, the joint–WDF cannot be described as a product of the two (one-dimensional) marginal probability densities either.

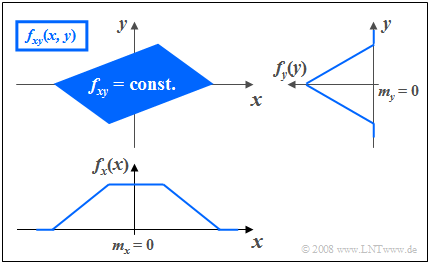

$\text{Example 3:}$ The graph shows the instantaneous values of a two-dimensional random variable in the $(x, y)$–plane, where now, unlike $\text{Example 2}$ there are statistical bindings between $x$ and $y$ .

- The 2D–random variable takes all 2D–values with equal probability in the parallelogram drawn in blue.

- No values are possible outside the parallelogram.

One recognizes from this representation:

- Integration over $f_{xy}(x, y)$ parallel to $x$–axis leads to the triangular marginal density $f_{y}(y)$, integration parallel to $y$–axis to the trapezoidal WDF $f_{x}(x)$.

- From the 2D WDF $f_{xy}(x, y)$ it can already be guessed that for each $x$–value on statistical average a different $y$–value is to be expected.

- This means that here the components $x$ and $y$ are statistically dependent on each other.

Expected values of two-dimensional random variables

A special case of statistical dependence is correlation.

$\text{Definition:}$ Under correlation one understands a linear dependence between the individual components $x$ and $y$.

- Correlated random variables are thus always also statistically dependent.

- But not every statistical dependence implies correlation at the same time

.

To quantitatively capture correlation, one uses various expected values of the 2D random variable $(x, y)$.

These are defined analogously to the one-dimensional case.

- according to Chapter 2 (for discrete value random variables).

- bzw. Chapter 3 (for continuous value random variables):

$\text{Definition:}$ For the (non-centered) moments the relation holds:

- $$m_{kl}={\rm E}\big[x^k\cdot y^l\big]=\int_{-\infty}^{+\infty}\hspace{0.2cm}\int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} x\hspace{0.05cm}^{k} \cdot y\hspace{0.05cm}^{l} \cdot f_{xy}(x,y) \, {\rm d}x\, {\rm d}y.$$

Thus, the two linear means are $m_x = m_{10}$ and $m_y = m_{01}.$

$\text{definition:}$ The $m_x$ and $m_y$ related central moments respectively are:

- $$\mu_{kl} = {\rm E}\big[(x-m_{x})\hspace{0.05cm}^k \cdot (y-m_{y})\hspace{0.05cm}^l\big] .$$

In this general definition equation, the variances $σ_x^2$ and $σ_y^2$ of the two individual components are included by $\mu_{20}$ and $\mu_{02}$ respectively.

$\text{Definition:}$ Of particular importance is the covariance $(k = l = 1)$, which is a measure of the linear statistical dependence between the random variables $x$ and $y$ :

- $$\mu_{11} = {\rm E}\big[(x-m_{x})\cdot(y-m_{y})\big] = \int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} \int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} (x-m_{x}) \cdot (y-m_{y})\cdot f_{xy}(x,y) \,{\rm d}x \, {\rm d}y .$$

In the following, we also denote the covariance $\mu_{11}$ in part by $\mu_{xy}$, if the covariance refers to the random variables $x$ and $y$

Notes:

- The covariance $\mu_{11}=\mu_{xy}$ is related to the non-centered moment $m_{11} = m_{xy} = {\rm E}\big[x \cdot y\big]$ as follows:

- $$\mu_{xy} = m_{xy} -m_{x }\cdot m_{y}.$$

- This equation is enormously advantageous for numerical evaluations, since $m_{xy}$, $m_x$ and $m_y$ can be found from the sequences $〈x_v〉$ and $〈y_v〉$ in a single run.

- On the other hand, if one were to calculate the covariance $\mu_{xy}$ according to the above definition equation, one would have to find the mean values $m_x$ and $m_y$ in a first run and could then only calculate the expected value ${\rm E}\big[(x - m_x) \cdot (y - m_y)\big]$ in a second run.

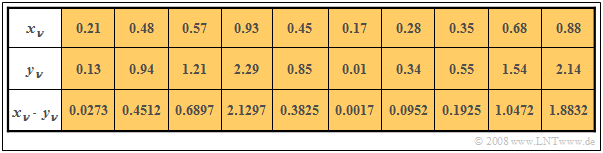

$\text{Example 4:}$ In the first two rows of the table, the respective first elements of two random sequences $〈x_ν〉$ and $〈y_ν〉$ are entered. In the last row, the respective products $x_ν - y_ν$ are given.

- By averaging over the ten sequence elements in each case, one obtains

- $$m_x =0.5,\ \ m_y = 1, \ \ m_{xy} = 0.69.$$

- This directly results in the value for the covariance:

- $$\mu_{xy} = 0.69 - 0.5 · 1 = 0.19.$$

Without knowledge of the equation $\mu_{xy} = m_{xy} - m_x\cdot m_y$ one would have had to first determine the mean values $m_x$ and $m_y$ in the first run,

in order to then determine the covariance $\mu_{xy}$ as the expected value of the product of the mean-free variables in a second run.

Correlation coefficient

With statistical independence of the two components $x$ and $y$ the covariance $\mu_{xy} \equiv 0$. This case has already been considered in $\text{Example 2}$ on the WDF and VTF for statistically independent components page.

- But the result $\mu_{xy} = 0$ is also possible for statistically dependent components $x$ and $y$ namely when they are uncorrelated, i.e. linearly independent .

- The statistical dependence is then not of first order, but of higher order, for example corresponding to the equation $y=x^2.$

One speaks of complete correlation when the (deterministic) dependence between $x$ and $y$ is expressed by the equation $y = K · x$ . Then the covariance is given by:

- $\mu_{xy} = σ_x · σ_y$ with positive value of $K$,

- $\mu_{xy} = - σ_x · σ_y$ with negative $K$–value.

Therefore, instead of covariance, one often uses the so-called correlation coefficient as a descriptive variable.

$\text{Definition:}$ The correlation coefficient is the quotient of the covariance $\mu_{xy}$ and the product of the rms values $σ_x$ and $σ_y$ of the two components:

- $$\rho_{xy}=\frac{\mu_{xy} }{\sigma_x \cdot \sigma_y}.$$

The correlation coefficient $\rho_{xy}$ has the following properties:

- Because of normalization, $-1 \le ρ_{xy} ≤ +1$ always holds.

- If the two random variables $x$ and $y$ are uncorrelated, then $ρ_{xy} = 0$.

- For strict linear dependence between $x$ and $y$ is $ρ_{xy}= ±1$ ⇒ complete correlation.

- A positive correlation coefficient means that when $x$ is larger, on statistical average $y$ is also larger than when $x$ is smaller.

- In contrast, a negative correlation coefficient expresses that $y$ becomes smaller on average as $x$ increases.

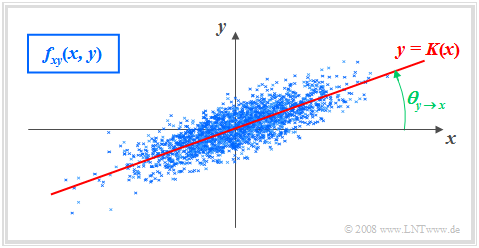

$\text{Example 5:}$ The following conditions apply:

- The considered components $x$ and $y$ each have a Gaussian WDF.

- The two scatterers are different $(σ_y < σ_x)$.

- The correlation coefficient is $ρ_{xy} = 0.8$.

Unlike the Example 2 with statistically independent components ⇒ $ρ_{xy} = 0$ $($drotz $σ_y < σ_x)$ one recognizes that here with larger $x$-value on statistical average also $y$ is larger than with smaller $x$.

Korrelationsgerade

$\text{Definition:}$ Als Korrelationsgerade bezeichnet man die Gerade $y = K(x)$ in der $(x, y)$–Ebene durch den „Mittelpunkt” $(m_x, m_y)$. Manchmal wird diese Gerade auch Regressionsgerade genannt.

Die Korrelationsgerade besitzt folgende Eigenschaften:

- Die mittlere quadratische Abweichung von dieser Geraden – in $y$–Richtung betrachtet und über alle $N$ Punkte gemittelt – ist minimal:

- $$\overline{\varepsilon_y^{\rm 2} }=\frac{\rm 1}{N} \cdot \sum_{\nu=\rm 1}^{N}\; \;\big [y_\nu - K(x_{\nu})\big ]^{\rm 2}={\rm Minimum}.$$

- Die Korrelationsgerade kann als eine Art „statistische Symmetrieachse“ interpretiert werden. Die Geradengleichung lautet:

- $$y=K(x)=\frac{\sigma_y}{\sigma_x}\cdot\rho_{xy}\cdot(x - m_x)+m_y.$$

Der Winkel, den die Korrelationsgerade zur $x$–Achse einnimmt, beträgt:

- $$\theta_{y\hspace{0.05cm}\rightarrow \hspace{0.05cm}x}={\rm arctan}\ (\frac{\sigma_{y} }{\sigma_{x} }\cdot \rho_{xy}).$$

Durch diese Nomenklatur soll deutlich gemacht werden, dass es sich hier um die Regression von $y$ auf $x$ handelt.

- Die Regression in Gegenrichtung – also von $x$ auf $y$ – bedeutet dagegen die Minimierung der mittleren quadratischen Abweichung in $x$–Richtung.

- Das interaktive Applet Korrelationskoeffizient und Regressionsgerade verdeutlicht, dass sich im Allgemeinen $($falls $σ_y \ne σ_x)$ für die Regression von $x$ auf $y$ ein anderer Winkel und damit auch eine andere Regressionsgerade ergeben wird:

- $$\theta_{x\hspace{0.05cm}\rightarrow \hspace{0.05cm} y}={\rm arctan}\ (\frac{\sigma_{x}}{\sigma_{y}}\cdot \rho_{xy}).$$

Aufgaben zum Kapitel

Aufgabe 4.1: Dreieckiges (x, y)-Gebiet

Aufgabe 4.1Z: Verabredung zum Frühstück

Aufgabe 4.1: Wieder Dreieckgebiet

Aufgabe 4.2Z: Korrelation zwischen $x$ und $e^x$

Aufgabe 4.3: Algebraische und Modulo-Summe

Aufgabe 4.3Z: Diracförmige 2D-WDF