Contents

- 1 Joint description of amplitude and angle modulation

- 2 A very simple (though unfortunately not always correct) modulator equation

- 3 Modulated signals with a digital source signal

- 4 Describing the physical signal using the analytical signal

- 5 Beschreibung des physikalischen Signals mit Hilfe des äquivalenten TP-Signals

- 6 Aufgaben zum Kapitel

Joint description of amplitude and angle modulation

In the following two chapters Amplitude Modulation (AM) and Angle Modulation (WM – from German "Winkelmodulation", including PM as well as FM) we will always consider the set-up shown in the image on the right. Here, the central block is the Modulator.

The two input signals and the output signal have the following characteristics::

- The source signal $q(t)$ is the low frequency message signal and has the spectrum $Q(f)$. This signal is continuous in value and time and limited to the frequency range $|f| ≤ B_{\rm NF}$ (NF from German "Niederfrequenz" i.e. low frequency).

- The carrier signal $z(t)$ is a harmonic oscillation of the form

- $$z(t) = A_{\rm T} \cdot \cos(2 \pi f_{\rm T} t - \varphi_{\rm T})= A_{\rm T} \cdot \cos(2 \pi f_{\rm T} t + \phi_{\rm T})\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- The transmission signal $s(t)$ is a higher frequency signal, whose spectral function $S(f)$ is in the range around the carrier frequency $f_{\rm T}$ .

The modulator output signal $s(t)$ depends on both input signals $q(t)$ and $z(t)$ . The modulation methods considered below differ only by different combinations of $q(t)$ and $z(t)$.

$\text{Definition:}$ Each Harmonic Oscillation $z(t)$ can be described by

- the amplitude $A_{\rm T}$,

- the frequency $f_{\rm T}$ and

- the zero phase position ${\it ϕ}_{\rm T}$ .

Though the above left equation with a minus sign and $φ_{\rm T}$ is mostly used for the application of Fourier series and Fourier integrals, the right equation with ${\it ϕ}_{\rm T} = \ – φ_{\rm T}$ and a plus sign is more common for the description of modulation processes.

A very simple (though unfortunately not always correct) modulator equation

$\text{Definition:}$ starting from the harmonic oscillation (here written with the angular frequency $ω_{\rm T} = 2πf_{\rm T}$ )

- $$z(t) = A_{\rm T} \cdot \cos(\omega_{\rm T}\cdot t + \phi_{\rm T})$$

we arrive at the general modulator equation, by assuming the previously fixed oscillation parameters to be time-dependent:

- $$s(t) = a(t) \cdot \cos \big[\omega(t) \cdot t + \phi(t)\big ]\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

$\text{!! Attention !!}$ This general modulator equation is very simple and striking and aids in understanding modulation methods. Unfortunately, this equation is true for frequency modulation only in exceptional cases. This will be discussed further in the chapter Signal characteristics in frequency modulation .

Special cases included in this equation are:

- In amplitude modulation $\rm (AM)$, the time-dependent amplitude $a(t)$ changes according to the source signal $q(t)$, while the other two signal parameters stay constant:

- $$\omega(t) = \omega_{\rm T} = {\rm const.}\hspace{0.08cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}\phi(t) = \phi_{\rm T} = {\rm const.}\hspace{0.08cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} a(t) = {\rm function \hspace{0.15cm}of}\hspace{0.15cm}q(t) .$$

- In frequency modulation $\rm (FM)$, only the instantaneous (circular) frequency $\omega(t)$ is determined by the source signal $q(t)$ :

- $$a(t) = A_{\rm T} = {\rm const.}\hspace{0.08cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}\phi(t) = \phi_{\rm T} = {\rm const.}\hspace{0.08cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} \omega(t)= {\rm function \hspace{0.15cm}of}\hspace{0.15cm}q(t) .$$

- In phase modulation $\rm (PM)$, the phase $\phi(t)$ varies according to the source signal $q(t)$:

- $$a(t) = A_{\rm T} = {\rm const.}\hspace{0.08cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}\omega(t) = \omega_{\rm T} = {\rm const.}\hspace{0.08cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} \phi(t) = {\rm function \hspace{0.15cm}of}\hspace{0.15cm}q(t) .$$

In these basic methods, two of the three oscillation parameters are thus always kept constant.

- Additionally, there are also variants with more than one time dependency for amplitude, frequency, and phase, respectively.

- An example of this is Single-Sideband Modulation, where both $a(t)$ and ${\it ϕ}(t)$ are affected by the source signal $q(t)$ .

Modulated signals with a digital source signal

When describing $\rm AM$, $\rm FM$ and $\rm PM$, the source signal $q(t)$ is usually assumed to be continuous in time and value.

- However, the above equations can also be applied to a rectangular source signal.

- In this case, $q(t)$ is continuous in time but discrete in value. Thus, it also describes methods for Linear Digital Modulation .

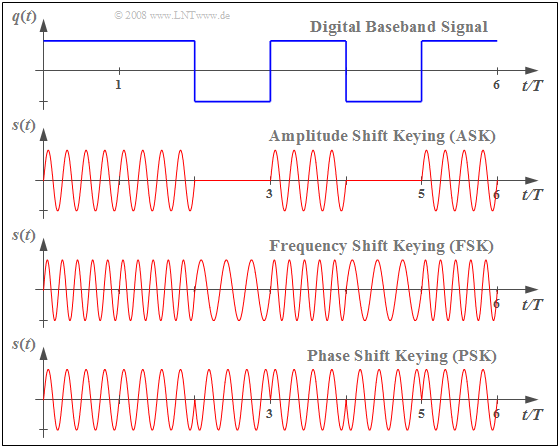

$\text{Example 1:}$ The graph shows a rectangular source signal $q(t)$ ⇒ Baseband signal, at the top, and the modulated signals $s(t)$ which result from important digital modulation methods drawn underneath.

- In amplitude modulation, the digital variant of which is known as Amplitude Shift Keying $\rm (ASK)$ , the message signal can be seen in the $s(t)$ envelope.

- In theFrequency Shift Keying $\rm (FSK)$ signal waveform, the two possible signal values $q(t) = +1$ and $q(t) =-1$ are represented by two different frequencies, respectively.

- Phase Shift Keying $\rm (PSK)$ results in phase jumps in the signal $s(t)$ when the amplitude of the source signal $q(t)$ jumps, by $\pm π$ (or $\pm 180^\circ$) in each binary case.

Describing the physical signal using the analytical signal

The modulated signal $s(t)$ is bandpass. As already described in the book „Signal Representation”, a BP signal $s(t)$ is often characterized by its associated analytical signall $s_+(t)$ . It is important to note:

- The analytical signal $s_+(t)$ is obtained from the real physical signal $s(t)$, by adding to it, as an imaginary part, itsHilbert transform:

- $$s_+(t) = s(t) + {\rm j} \cdot {\rm H}\{ s(t)\}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- Das analytische Signal $s_+(t)$ ist somit stets komplex. Zwischen den beiden Zeitsignalen gilt der folgende einfache Zusammenhang:

- $$s(t) = {\rm Re} \big[s_+(t)\big] \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- Das Spektrum $S_+(f)$ des analytischen Signals ergibt sich aus dem zweiseitigen Spektrum $S(f)$, wenn man dieses bei positiven Frequenzen verdoppelt und für negative Frequenzen zu Null setzt:

- $$S_+(f) =\big[ 1 + {\rm sign}(f)\big] \cdot S(f) = \left\{ \begin{array}{c} 2 \cdot S(f) \\ 0 \\ \end{array} \right.\quad \begin{array}{*{10}c} {\rm{f\ddot{u}r}} \\ {\rm{f\ddot{u}r}} \\ \end{array}\begin{array}{*{20}c} f>0 \hspace{0.05cm}, \\ f<0 \hspace{0.05cm}, \\ \end{array} \hspace{1.3cm} \text{mit}\hspace{1.3cm} {\rm sign}(f) = \left\{ \begin{array}{c} +1 \\ -1 \\ \end{array} \right.\quad \begin{array}{*{10}c} {\rm{f\ddot{u}r}} \\ {\rm{f\ddot{u}r}} \\ \end{array}\begin{array}{*{20}c} f>0 \hspace{0.05cm}, \\ f<0 \hspace{0.05cm}. \\ \end{array}$$

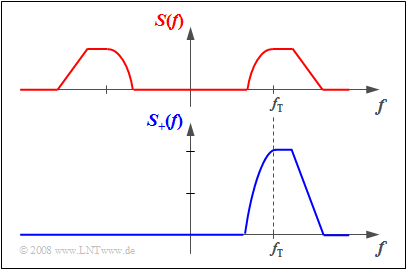

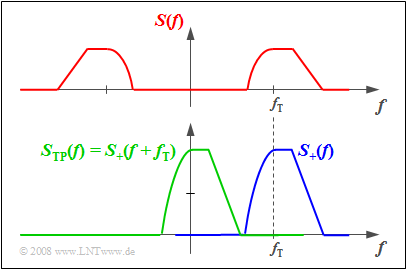

$\text{Beispiel 2:}$ Die obere Grafik zeigt das Spektrum $S(f)$ eines reellen Zeitsignals $s(t)$. Man erkennt:

- Die Achsensymmetrie der Spektralfunktion $S(f)$ bezüglich der Frequenz $f=0$:

- $${\rm Re}\big[S( - f)\big] = {\rm Re}\big[S(f)\big].$$

- Hätte das Spektrum des reellen Zeitsignals $s(t)$ einen Imaginärteil, so wäre dieser punktsymmetrisch um $f=0$:

- $${\rm Im}\big[S( - f)\big] = - {\rm Im}\big[S(f)\big].$$

Unten ist das Spektrum $S_+(f)$ des zugehörigen analytischen Signals $s_+(t)$ dargestellt. Dieses ergibt sich aus $S(f)$ durch

- Abschneiden der negativen Frequenzanteile: $S_+(f) \equiv 0$ für $f<0$,

- Verdoppeln der positiven Frequenzanteile: $S_+(f ) = 2 \cdot S(f )$ für $f \ge 0$.

Bis auf einen nicht praxisrelevanten Sonderfall ist das analytische Signal $s_+(t)$ stets komplex.

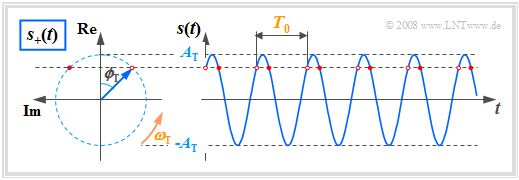

Wir wenden nun diese Definitionen auf das modulierte Signal $s(t)$ an. Im Sonderfall $q(t) \equiv 0$ ist $s(t)$ wie das Trägersignal $z(t)$ eine harmonische Schwingung. Es gilt:

- $$s(t) = A_{\rm T} \cdot \cos(\omega_{\rm T}\cdot t + \phi_{\rm T}) \hspace{0.3cm} \Leftrightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} s_+(t) = A_{\rm T} \cdot {\rm e}^{\hspace{0.03cm}{\rm j} \hspace{0.03cm}(\omega_{\rm T}\hspace{0.05cm} t \hspace{0.05cm} + \phi_{\rm T})}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

Die zweite Gleichung beschreibt einen Drehzeiger mit folgenden Eigenschaften:

- Die Zeigerlänge kennzeichnet die Signalamplitude $A_{\rm T}$.

- Zur Zeit $t = 0$ liegt der Zeiger mit dem Winkel $ϕ_{\rm T}$ in der komplexen Ebene.

- Für $t > 0$ dreht der Zeiger mit konstanter Winkelgeschwindigkeit $ω_{\rm T}$ in mathematisch positive Richtung (entgegen dem Uhrzeigersinn).

- Die Zeigerspitze liegt stets auf einem Kreis mit dem Radius $A_{\rm T}$ und benötigt für eine Umdrehung genau die Periodendauer $T_0$.

Um den Zusammenhang $s(t) = {\rm Re}[s_+(t)]$ im Querformat zeigen zu können, ist die komplexe Ebene entgegen der üblichen Darstellung um $90^\circ$ nach links gedreht:

Der Realteil ist nach oben und der Imaginärteil nach links aufgetragen.

Die einzelnen Modulationsverfahren lassen sich nun wie folgt darstellen:

- Bei der Amplitudenmodulation ändert sich die Zeigerlänge $a(t) = |s_+(t)|$ und damit die Hüllkurve von $s(t)$ entsprechend dem Quellensignal $q(t)$.

Die Winkelgeschwindigkeit $ω(t)$ ist dabei konstant. - Bei der Frequenzmodulation ändert sich die Winkelgeschwindigkeit $ω(t)$ des rotierenden Zeigers entsprechend $q(t)$,

während die Zeigerlänge $a(t) = A_{\rm T}$ nicht verändert wird. - Bei der Phasenmodulation ist die Phase $ϕ(t)$ zeitabhängig.

Es bestehen viele Gemeinsamkeiten mit der Frequenzmodulation, die ebenfalls zur Klasse der Winkelmodulation zählt.

Beschreibung des physikalischen Signals mit Hilfe des äquivalenten TP-Signals

Manche Sachverhalte bezüglich der sendeseitigen Modulation und der Demodulation am Empfänger lassen sich anhand des äquivalenten Tiefpass–Signals entsprechend der Definition im Buch „Signaldarstellung” anschaulich am besten erklären.

Für dieses Signal $s_{\rm TP}(t)$ und dessen Spektrum $S_{\rm TP}(f)$ gelten die folgenden Aussagen:

- Das Spektrum $S_{\rm TP}(f)$ des äquivalenten Tiefpass–Signals erhält man aus $S_+(f)$ durch Verschiebung um $f_{\rm T}$ nach links und liegt somit im Bereich um die Frequenz $f =0$:

- $$S_{\rm TP}(f) = S_+(f + f_{\rm T}) \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- Für die zugehörige Zeitfunktion gilt nach dem Verschiebungssatz:

- $$s_{\rm TP}(t) = s_+(t) \cdot {\rm e}^{{-\rm j}\hspace{0.08cm} \omega_{\rm T} \hspace{0.03cm}t }\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- Das äquivalente Tiefpass–Signal einer unmodulierten harmonischen Schwingung ist für alle Zeiten konstant – die Ortskurve besteht in diesem Sonderfall aus einem einzigen Punkt:

- $$s(t) = A_{\rm T} \cdot \cos(\omega_{\rm T}\cdot t + \phi_{\rm T}) \hspace{0.3cm} \Leftrightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} s_+(t) = {\rm e}^{\hspace{0.03cm}{\rm j} \hspace{0.03cm}(\omega_{\rm T}\hspace{0.05cm} t \hspace{0.05cm} + \phi_{\rm T})}\hspace{0.05cm},$$

- $$ s_+(t) = {\rm e}^{\hspace{0.03cm}{\rm j} \hspace{0.03cm}(\omega_{\rm T}\hspace{0.05cm} t \hspace{0.05cm} + \phi_{\rm T})}\hspace{0.3cm} \Leftrightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} s_{\rm TP}(t) = A_{\rm T} \cdot {\rm e}^{\hspace{0.03cm}{\rm j} \hspace{0.03cm} \cdot \hspace{0.05cm} \phi_{\rm T}}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

$\text{Wichtiges Ergebnis:}$ Für ein amplituden– oder phasenmoduliertes Signal mit der Trägerfrequenz $f_{\rm T}$ gilt dagegen:

- $$s(t) = a(t) \cdot \cos(\omega_{\rm T}\cdot t + \phi(t)) \hspace{0.3cm} \Leftrightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} s_{\rm TP}(t) = a(t) \cdot {\rm e}^{\hspace{0.03cm}{\rm j} \hspace{0.03cm} \cdot \hspace{0.05cm} \phi (t)}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

Die Hüllkurve $a(t)$ und der Phasenverlauf $ϕ(t)$ des (physikalischen) Bandpass-Signals $s(t)$ bleiben auch im äquivalenten TP–Signal $s_{\rm TP}(t)$ erhalten.

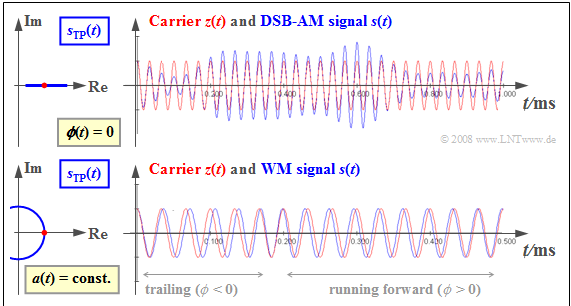

$\text{Beispiel 3:}$ Die Grafik zeigt jeweils rechts das modulierte Signal $s(t)$ ⇒ roter Signalverlauf im Vergleich zum Trägersignal $z(t)$ ⇒ blauer Signalverlauf.

Links dargestellt sind die jeweiligen äquivalenten Tiefpass–Signale $s_{\rm TP}(t)$ ⇒ grüne Ortskurven.

Oben ist die Amplitudenmodulation beschrieben, bei der das Quellensignal $q(t)$ in der Hüllkurve $a(t)$ zu erkennen ist:

- Da die Nulldurchgänge des Trägers $z(t)$ erhalten bleiben, ist $ϕ(t) = 0$ und das äquivalente TP–Signal $s_{\rm TP}(t) = a(t)$ reell.

- Die Herleitung dieses Sachverhalts erfolgt im Kapitel Beschreibung mit Hilfe des äquivalenten TP-Signals.

Unten ist die Winkelmodulation verdeutlicht.

- Hier ist die Hüllkurve $a(t)$ konstant ⇒ das äquivalente TP-Signal $s_{\rm TP}(t) = A_{\rm T} · e^{\rm j·ϕ(t)}$ beschreibt einen Kreisbogen.

- Die Information über das Nachrichtensignal $q(t)$ steckt hier in der Lage der Nulldurchgänge von $s(t)$.

- Genaueres hierüber finden Sie im Kapitel Gemeinsamkeiten zwischen PM und FM

Hinweise:

- Wir bezeichnen im Folgenden den zeitabhängigen Verlauf von $s_{\rm TP}(t)$ in der komplexen Ebene auch als "Ortskurve", während das "Zeigerdiagramm" den Verlauf des analytischen Signals $s_+(t)$ beschreibt.

- Der hier dargelegte Sachverhalt wird mit zwei interaktiven Applets im Zeitbereich verdeutlicht:

Aufgaben zum Kapitel

Aufgabe 1.4: Zeigerdiagramm und Ortskurve

Aufgabe 1.4Z: Darstellungsformen von Schwingungen