Difference between revisions of "Linear and Time Invariant Systems/Nonlinear Distortions"

| Line 73: | Line 73: | ||

[[File:EN_LZI_T_2_2_S3.png|right|frame|Definition of the distortion factor|class=fit]] | [[File:EN_LZI_T_2_2_S3.png|right|frame|Definition of the distortion factor|class=fit]] | ||

| − | To quantitatively capture the | + | To quantitatively capture the nonlinear distortions we assume that the input signal $x(t)$ is cosine-shaped with the amplitude $A_x$ . |

The output signal contains harmonics due to the nonlinear distortions and the following is generally true: | The output signal contains harmonics due to the nonlinear distortions and the following is generally true: | ||

| Line 100: | Line 100: | ||

\frac{ {1}/{2} \cdot A_{x}^2}{{1}/{2} \cdot (A_{2}^2 + A_{3}^2 + A_{4}^2 + \hspace{0.05cm}...) } = \frac{1}{K^2}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | \frac{ {1}/{2} \cdot A_{x}^2}{{1}/{2} \cdot (A_{2}^2 + A_{3}^2 + A_{4}^2 + \hspace{0.05cm}...) } = \frac{1}{K^2}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| − | [[File:P_ID1090__LZI_T_2_2_S3b_neu.png |frame|Influence of a | + | [[File:P_ID1090__LZI_T_2_2_S3b_neu.png |frame|Influence of a nonlinearity on a cosine signal | right|class=fit]] |

{{GraueBox|TEXT= | {{GraueBox|TEXT= | ||

$\text{Example 2:}$ | $\text{Example 2:}$ | ||

| Line 109: | Line 109: | ||

:$$P_x = 1/4 + 1/8 = 0.375.$$ | :$$P_x = 1/4 + 1/8 = 0.375.$$ | ||

| − | + | If we apply this signal to a nonlinearity with the characteristic curve | |

:$$y=g(x) = \sin(x) \approx x - {x^3}/{6} \hspace{0.05cm},$$ | :$$y=g(x) = \sin(x) \approx x - {x^3}/{6} \hspace{0.05cm},$$ | ||

| − | + | then the output signal is: | |

:$$y(t) = A_0 + A_1 \cdot \cos (\omega_0 \cdot t)+ A_2 \cdot \cos (2\omega_0 \cdot t)+ A_3 \cdot \cos (3\omega_0 \cdot t)\hspace{0.05cm},$$ | :$$y(t) = A_0 + A_1 \cdot \cos (\omega_0 \cdot t)+ A_2 \cdot \cos (2\omega_0 \cdot t)+ A_3 \cdot \cos (3\omega_0 \cdot t)\hspace{0.05cm},$$ | ||

:$$\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} A_0 = {86}/{192},\hspace{0.3cm}A_1 = {81}/{192},\hspace{0.3cm}A_2 = - {6}/{192},\hspace{0.3cm}A_3 = - | :$$\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} A_0 = {86}/{192},\hspace{0.3cm}A_1 = {81}/{192},\hspace{0.3cm}A_2 = - {6}/{192},\hspace{0.3cm}A_3 = - | ||

{1}/{192}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | {1}/{192}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| − | + | The trigonometric transformations for $\cos^2(α)$ and $\cos^3(α)$ were used to calculate the Fourier coefficients. The distortion factor is thus given by | |

:$$K = \frac {\sqrt{A_2^{\hspace{0.05cm}2} + A_3^{\hspace{0.05cm}2} } }{A_1}\approx 7.5\%\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | :$$K = \frac {\sqrt{A_2^{\hspace{0.05cm}2} + A_3^{\hspace{0.05cm}2} } }{A_1}\approx 7.5\%\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| − | + | It can be further seen that the signal $y(t)$ sketched in red is almost equal to the signal $α · x(t)$ sketched in green with $α = \sin(1) ≈ 5/6$ . | |

| − | + | Defining the error signal as $ε_1(t) = y(t) - α · x(t)$, with its power | |

:$$P_{\varepsilon 1} = \frac {(80-86)^2}{192^2} + \frac {6^2 + (-1)^2}{2 \cdot 192^2}\approx 1.48 \cdot 10^{-3}$$ | :$$P_{\varepsilon 1} = \frac {(80-86)^2}{192^2} + \frac {6^2 + (-1)^2}{2 \cdot 192^2}\approx 1.48 \cdot 10^{-3}$$ | ||

| − | + | the following is obtained for the signal–to–Stör–power ratio: | |

:$$\rho_{{\rm V} 1} = \frac {\alpha^2 \cdot P_x}{P_{\varepsilon 1} } = \frac {(5/6)^2 \cdot 0.375}{1.48 \cdot 10^{-3} }\approx | :$$\rho_{{\rm V} 1} = \frac {\alpha^2 \cdot P_x}{P_{\varepsilon 1} } = \frac {(5/6)^2 \cdot 0.375}{1.48 \cdot 10^{-3} }\approx | ||

176 = {1}/{K^2}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | 176 = {1}/{K^2}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

Revision as of 10:13, 13 September 2021

Contents

Properties of nonlinear systems

The system description by means of the frequency response $H(f)$ and/or impulse response $h(t)$ is only possible for an LTI System . However, if the system also contains nonlinear components, as it is assumed for this chapter, no frequency response and no impulse response can be stated, and the model must be designed in a more general way.

Also, in this nonlinear system we denote the signals at the input and output by $x(t)$ and $y(t)$ respectively, and the corresponding spectral functions by $X(f)$ and $Y(f)$.

An observer will note the following here:

- The transmission characteristics are now also dependent on the amplitude of the input signal . If $x(t)$ results in the output signal $y(t)$, it can now no longer be concluded that the input signal $K · x(t)$ will always result in the signal $K · y(t)$ .

- This also implies that the superposition principle is no longer applicable . Consequently, the result $x_1(t) + x_2(t) ⇒ y_1(t) + y_2(t)$ cannot be reasoned from the two correspondences $x_1(t) ⇒ y_1(t)$ and $x_2(t) ⇒ y_2(t)$ .

- Due to nonlinearities new frequencies occur. If $x(t)$ is a harmonic oscillation with the frequency $f_0$, the output signal $y(t)$ also contains components at multiples of $f_0$. In communications engineering, these are referred to as harmonics.

- In practice, an information signal usually contains many frequency components. The harmonics of the low-frequency signal components now fall into the range of higher-frequency useful components. This results in nonreversible signal falsifications.

Before mentioning "constellations which result in nonlinear distortions" at the end of the section the problem of nonlinear distortions is captured mathematically.

- We assume here that the system has no memory so that the output value $y = y(t_0)$ depends only on the instantaneous input value $x = x(t_0)$

- but not on the signal curve $x(t)$ for $t < t_0$.

Description of nonlinear systems

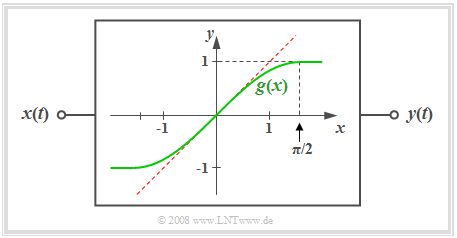

$\text{Definition:}$ A system is said to be nonlinear if the following relationship exists between the signal value $x = x(t)$ at the input and the output $y = y(t)$ : $$y = g(x) \ne {\rm const.} \cdot x.$$ The curve shape $y = g(x)$ is called the nonlinear characteristic curve of the system.

- In the diagram, as an example, the green curve is the nonlinear characteristic curve $y = g(x)$ which is shaped according to the first quarter of a sine function.

- The special case of a linear system with the characteristic curve $y = x$ can be seen dashed in red.

Since every characteristic curve can be developed into a Taylor series around the operating point the output signal can also be represented as follows: $$y(t) = \sum_{i=0}^{\infty}\hspace{0.1cm} c_i \cdot x^{i}(t) = c_0 + c_1 \cdot x(t) + c_2 \cdot x^{2}(t) + c_3 \cdot x^{3}(t) + \hspace{0.05cm}\text{...}$$ If $x(t)$ has a unit – for exmple "Volt” –, then the coefficients of the Taylor series also have appropriate and different units:

- $c_0$ with $\rm V$,

- $c_1$ without units,

- $c_2$ with $\rm 1/V$, etc.

In the above diagram, the operating point is identical to the zero point and $c_0 = 0$ holds.

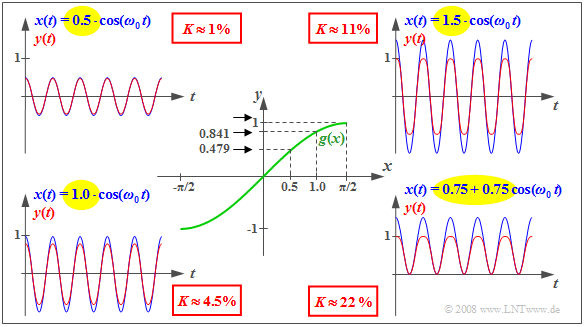

$\text{Example 1:}$ The properties of nonlinear systems listed on the first page of this section are illustrated here using the characteristic curve $y = g(x) = \sin(x)$ shown in the centre of the diagram.

- Here, the direct (DC) signal $x(t) = 0.5$ results in the constant output signal $y(t) = 0.479$ .

- For $x(t) = 1$ the input signal results in the output signal $y(t) = 0.841 ≠ 2 · 0.479$.

- Thus, doubling $x(t)$ does not cause the doubling of $y(t)$ ⇒ the superposition principle is violated.

The outer diagrams show – each in blue – cosine-shaped input signals $x(t)$ with different amplitudes $A$ and the corresponding distorted output signals $y(t)$ in red. It can be seen that the nonlinear distortions increase with increasing amplitude, which are quantified by the distortion factor $K$ defined on the next page.

- The diagram on the upper right-hand corner for $A = 1.5$ clearly shows that $y(t)$ is no longer cosine-shaped; the half-waves run rounder than the ones of the cosine function.

- But also for $A = 0.5$ and $A = 1.0$ the signals $y(t)$ deviate - although less strongly - from the cosine form due to the harmonics. That is, new frequency components at multiples of the cosine frequency $f_0$ arise.

- In the picture on the bottom right-hand corner the characteristic curve is operated unilaterally due to an additional direct component. Now an unbalance in the signal $y(t)$ can be seen, too. The lower half-wave is more peaked than the upper one. The distortion factor here is $K \approx 22\%$.

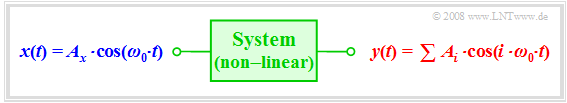

The distortion factor

To quantitatively capture the nonlinear distortions we assume that the input signal $x(t)$ is cosine-shaped with the amplitude $A_x$ .

The output signal contains harmonics due to the nonlinear distortions and the following is generally true:

$$y(t) = A_0 + A_1 \cdot \cos(\omega_0 t) + A_2 \cdot \cos(2\omega_0 t) +

A_3 \cdot \cos(3\omega_0 t) + \hspace{0.05cm}...$$

$\text{Definition:}$ With these amplitude values $A_i$ the equation for the distortion factor is:

- $$K = \frac {\sqrt{A_2^2+ A_3^2+ A_4^2+ \hspace{0.05cm}\text{...} } }{A_1} = \sqrt{K_2^2+ K_3^2+K_4^2+ \hspace{0.05cm}\text{...} }.$$

In the second equation

- $K_2 = A_2/A_1$ denotes the distortion factor of second order,

- $K_3 = A_3/A_1$ denotes the distortion factor of third order, etc.

It is explicitly pointed out that the amplitude $A_x$ of the input signal is not taken into account when computing the distortion factor. AAlso a resulting direct (DC) component $A_0$ is not taken into account.

In the last section of $\text{Example 1}$ the distortion factors were specified with values between about $1\%$ and $20\%$ .

- These values are already significantly above the distortion factors of low-cost audio equipment, for which $K < 0.1\%$ applies.

- In HiFi equipment, particular emphasis is placed on linearity and a very low distortion factor is also reflected in the price.

A comparison with the page Berücksichtigung von Dämpfung und Laufzeit reveals that for the special case of a cosine-shaped input signal the signal–to–distortion–power ratio defined is equal to the reciprocal of the distortion factor squared:

- $$\rho_{\rm V} = \frac{ \alpha^2 \cdot P_{x}}{P_{\rm V}} = \left(\frac{ A_{1}}{A_x} \right)^2 \cdot \frac{ {1}/{2} \cdot A_{x}^2}{{1}/{2} \cdot (A_{2}^2 + A_{3}^2 + A_{4}^2 + \hspace{0.05cm}...) } = \frac{1}{K^2}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

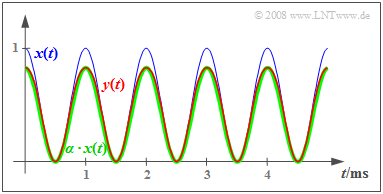

$\text{Example 2:}$ We now consider an averaged cosine signal:

- $$x(t) = {1}/{2} + {1}/{2}\cdot \cos (\omega_0 \cdot t).$$

$x(t)$ takes values between $0$ and $1$ , and is drawn as the blue curve. The signal power is

- $$P_x = 1/4 + 1/8 = 0.375.$$

If we apply this signal to a nonlinearity with the characteristic curve

- $$y=g(x) = \sin(x) \approx x - {x^3}/{6} \hspace{0.05cm},$$

then the output signal is:

- $$y(t) = A_0 + A_1 \cdot \cos (\omega_0 \cdot t)+ A_2 \cdot \cos (2\omega_0 \cdot t)+ A_3 \cdot \cos (3\omega_0 \cdot t)\hspace{0.05cm},$$

- $$\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} A_0 = {86}/{192},\hspace{0.3cm}A_1 = {81}/{192},\hspace{0.3cm}A_2 = - {6}/{192},\hspace{0.3cm}A_3 = - {1}/{192}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

The trigonometric transformations for $\cos^2(α)$ and $\cos^3(α)$ were used to calculate the Fourier coefficients. The distortion factor is thus given by

- $$K = \frac {\sqrt{A_2^{\hspace{0.05cm}2} + A_3^{\hspace{0.05cm}2} } }{A_1}\approx 7.5\%\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

It can be further seen that the signal $y(t)$ sketched in red is almost equal to the signal $α · x(t)$ sketched in green with $α = \sin(1) ≈ 5/6$ .

Defining the error signal as $ε_1(t) = y(t) - α · x(t)$, with its power

- $$P_{\varepsilon 1} = \frac {(80-86)^2}{192^2} + \frac {6^2 + (-1)^2}{2 \cdot 192^2}\approx 1.48 \cdot 10^{-3}$$

the following is obtained for the signal–to–Stör–power ratio:

- $$\rho_{{\rm V} 1} = \frac {\alpha^2 \cdot P_x}{P_{\varepsilon 1} } = \frac {(5/6)^2 \cdot 0.375}{1.48 \cdot 10^{-3} }\approx 176 = {1}/{K^2}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

Dagegen ist das SNR deutlich geringer, wenn man den Dämpfungsfaktor $α$ nicht berücksichtigt, das heißt, wenn man vom Fehlersignal $ε_2 = y(t) - x(t)$ ausgeht:

- $$P_{\varepsilon 2} = \frac {(86-96)^2}{192^2} + \frac {(81-96)^2 + 6^2 + (-1)^2}{2 \cdot 192^2}\approx 6.3 \cdot 10^{-3} \hspace{0.3cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}\rho_{{\rm V} 2} = \frac { P_x}{P_{\varepsilon 2}}= \frac {0.375}{6.3 \cdot 10^{-3}} \approx 60 \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

Clirr measurement

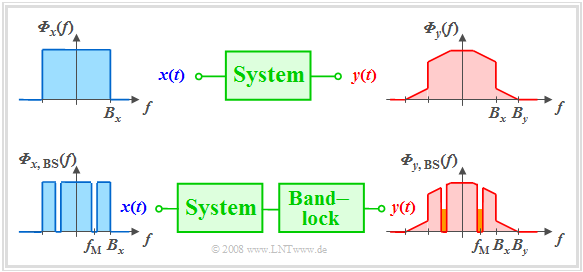

Ein großer Nachteil der Klirrfaktordefinition ist die damit einhergehende Festlegung auf cosinusförmige Testsignale, also auf realitätsferne Bedingungen.

- Bei der so genannten Rauschklirrmessung modelliert man das zu übertragende Signal $x(t)$ durch weißes Rauschen mit der Rauschleistungsdichte ${\it \Phi}_x(f)$.

- Zusätzlich bringt man eine schmale Bandsperre $\rm (BS)$ mit Mittelfrequenz $f_{\rm M}$ und (sehr kleiner) Bandbreite $B_{\rm BS}$ in das System ein.

Bei einem linearen System wäre das Ausgangsspektrum ${\it \Phi}_y(f)$ nicht breiter als $B_x$ und auch im Bereich um $f_{\rm M}$ gäbe es keine Anteile.

Diese ergeben sich allein durch Mischprodukte (Intermodulationsanteile) verschiedener Spektralanteile, also durch nichtlineare Verzerrungen.

Durch Variation der Mittenfrequenz $f_{\rm M}$ und Integration über alle diese kleinen Störanteile kann somit die Verzerrungsleistung ermittelt werden. Nähere Angaben zu dieser Methode findet man zum Beispiel in [Kam04][1].

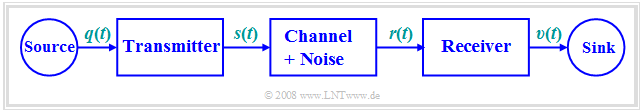

Constellations which result in nonlinear distortions

Als Beispiel für das Auftreten nichtlinearer Verzerrungen bei analogen Nachrichtenübertragungssystemen sollen hier einige Konstellationen genannt werden, die zu solchen führen. Inhaltlich bedeutet dies einen Vorgriff auf das Buch Modulation Methods.

Nichtlineare Verzerrungen des Sinkensignals $v(t)$ in Bezug zum Quellensignal $q(t)$ treten auf, wenn

- es bereits auf dem Kanal – also bezüglich des Sendesignals $s(t)$ und des Empfangssignals $r(t)$ – zu nichtlinearen Verzerrungen kommt,

- bei der Zweiseitenband–Amplitudenmodulation (ZSB–AM) mit Modulationsgrad $m > 1$ ein Hüllkurvendemodulator verwendet wird,

- bei ZSB–AM und Hüllkurvendemodulation ein linear verzerrender Kanal vorliegt und zwar auch bei einem Modulationsgrad $m < 1$,

- man die Kombination Einseitenband–AM und Hüllkurvendemodulation verwendet (unabhängig vom Seitenband–zu–Träger–Verhältnis),

- eine Winkelmodulation (Oberbegriff für Frequenz– und Phasenmodulation) angewandt wird und die zur Verfügung stehende Bandbreite nur endlich groß ist.

Exercises for the Chapter

Aufgabe 2.3: Sinusförmige Kennlinie

Aufgabe 2.3Z: Kennlinienbetrieb asymmetrisch

Aufgabe 2.4: Klirrfaktor und Verzerrungsleistung

Aufgabe 2.4Z: Kennlinienvermessung

List of sources

- ↑ Kammeyer, K.D.: Nachrichtenübertragung. Stuttgart: B.G. Teubner, 4. Auflage, 2004.