Difference between revisions of "Modulation Methods/Further AM Variants"

m |

m |

||

| Line 58: | Line 58: | ||

$\text{Definition:}$ A demodulator is said to be '''coherent''', if in addition to the required frequency synchronization, it requires accurate information about the phase of the transmit-side carrier signal $z(t)$ to reconstruct the message signal. | $\text{Definition:}$ A demodulator is said to be '''coherent''', if in addition to the required frequency synchronization, it requires accurate information about the phase of the transmit-side carrier signal $z(t)$ to reconstruct the message signal. | ||

| − | If this phase information is not required, the demodulator is said to be '''incoherent | + | If this phase information is not required, the demodulator is said to be an '''incoherent demodulator'''.}} |

| Line 64: | Line 64: | ||

{{GraueBox|TEXT= | {{GraueBox|TEXT= | ||

| − | $\text{Example 2:}$ | + | $\text{Example 2:}$ A second example is shown in the following block diagram. In contrast to quadrature amplitude modulation, here the orthogonality between cosine and sine functions is not used for the simultaneous transmission of a second source signal, but rather to simplify the receiver-side device. |

| − | [[File:P_ID1054__Mod_T_2_5_S3_neu.png |center|frame| | + | [[File:P_ID1054__Mod_T_2_5_S3_neu.png |center|frame|Incoherent demodulation with $\rm DSB-AM$]] |

| − | + | It should be further noted regarding this arrangement: | |

| − | * | + | *The receiver-side carrier signals can have an arbitrary and also time-dependent phase offset $Δϕ_{\rm T}$ with respect to the carrier signals at the transmitter, as long as the phase difference between the two branches remains exactly $90^\circ$ . |

| − | * | + | *For the signals in the upper and lower branches – after the multiplier and low-pass filtering, respectively – it holds: |

:$$b_1(t) = \cos(\Delta \phi_{\rm T}) \cdot q(t), $$ | :$$b_1(t) = \cos(\Delta \phi_{\rm T}) \cdot q(t), $$ | ||

:$$b_2(t) = -\sin(\Delta \phi_{\rm T}) \cdot q(t).$$ | :$$b_2(t) = -\sin(\Delta \phi_{\rm T}) \cdot q(t).$$ | ||

| − | * | + | *This ensures that the sink signal $v(t)$ matches the source signal $q(t)$ , at least in magnitude, regardless of the phase offset $Δϕ_{\rm T}$ : |

:$$v(t) = \sqrt{ b_1^2(t) + b_2^2(t)} = \sqrt{ q^2(t) } = \vert q(t) \vert \hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | :$$v(t) = \sqrt{ b_1^2(t) + b_2^2(t)} = \sqrt{ q^2(t) } = \vert q(t) \vert \hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| − | * | + | *A prerequisite for operability – that is, for the result $v(t) = q(t)$ – is that at all times $q(t) ≥ 0$ . In an analog message system, this fact could be enforced using the "DSB-AM with carrier" modulation method, for example. |

| − | * | + | *This form of non-coherent demodulation - or modifications of it - is mainly applied in some '''digital modulation methods''', which are discussed in detail in the fourth chapter of [[Modulation_Methods|this book]].}} |

| − | == | + | ==Exercises for the chapter== |

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | [[Aufgaben: | + | [[Aufgaben:Exercise_2.12:_Non-coherent_Demodulation|Exercise 2.12: Non-coherent Demodulation]] |

| − | [[Aufgaben: | + | [[Aufgaben:Exercise_2.13:_Quadrature_Amplitude_Modulation|Exercise 2.13: Quadrature Amplitude Modulation (QAM)]] |

| − | == | + | ==References== |

<references/> | <references/> | ||

{{Display}} | {{Display}} | ||

Revision as of 20:29, 22 December 2021

Contents

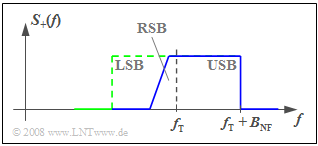

Vestigial sideband amplitude modulation

When transmitting signals using single sideband modulation $\rm (SSB–AM)$ the following problems occur:

- To suppress the unwanted sideband, a filter with a very high edge slope must be used.

- Such a steep-edged filters exhibit strong group delay distortions, especially at the limit of the passband.

the problem can be greatly mitigated if instead single-sideband AM one uses vestigial sideband amplitude modulation $\rm (VSB–AM)$ , as shown in the adjacent graph.

The present description is based on the textbook [Mäu88][1]. According to it, the VSB-AM can be characterized as follows:

- A certain frequency range of the actually suppressed sideband – in the considered example of the LSB – is additionally used with a relatively flat decreasing transfer function.

- On the receiver side, a selection curve linearly increasing in frequency with a so-called "Nyquist edge" is used in the transition range from the suppressed sideband to the transmitted sideband.

- The demodulation performs a convolution of the sidebands around the carrier, so that as a result the message content of a band with the same amplitude for all frequencies is obtained.

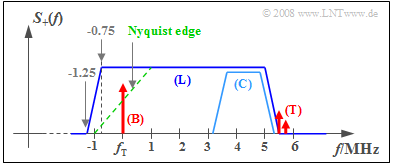

$\text{Example 1:}$ The vestigial sideband method is used for (analog) color television, whose frequency spectrum according to the CCIR standard is shown in the graphic. The frequencies given refer to the PAL–B/G Television format used in Germany.

In this schematic representation, one recognises:

- The radiated spectrum(only positive frequencies are drawn) ranges from $f_{\rm T} - 1.25 \ \rm MHz$ to $f_{\rm T} + 5.75 \ \rm MHz$. Thus, the lower vestigial sideband including the Nyquist edge is approximately $1.25 \ \rm MHz$ wide .

- The green dashed line shows the receiver passband. The image carrier (B) at carrier frequency $f_{\rm T}$ is centered on the Nyquist edge.

- The luminance signal (L) goes up to about $5 \ \rm MHz$. . It contains the information for the image brightness and the color "green".

- The chrominance signal (C) is embedded in the upper part. Two orthogonal carriers are QAM-modulated at $4.43 \ \rm MHz$ for "red" and "blue"; the carrier is suppressed.

- The audio carrier (T) (abbreviation T from German "Ton" i.e., sound/audio) is at $f_{\rm T} + 5.5 \ \rm MHz$ and is $12 \ \rm dB$ lower than the image carrier. If there is a stereo or two-channel sound transmission, a second sound carrier follows at $5.75 \ \rm MHz$ .

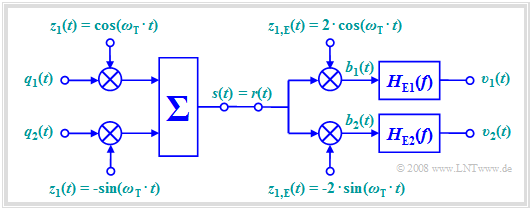

Quadrature Amplitude Modulation (QAM)

By exploiting the orthogonality of cosine and sine functions, a channel can be used twice for simultaneous transmission of two source signals $q_1(t)$ and $q_2(t)$ without mutual interference. This method is called quadrature amplitude modulation $\rm (QAM)$.

The QAM system has the following characteristics:

- The transmit signal is composed of two mutually orthogonal components:

- $$s(t) = q_1(t) \cdot \cos (\omega_{\rm T}\cdot t) - q_2(t) \cdot \sin (\omega_{\rm T}\cdot t)\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- For frequency and phase synchronous demodulation, the signal in the upper branch before the low pass is $H_{\rm E1}(f)$:

- $$b_1(t) = q_1(t) \cdot 2 \cdot \cos^2 (\omega_{\rm T}\cdot t) - q_2(t) \cdot 2 \cdot \cos (\omega_{\rm T}\cdot t)\cdot \sin (\omega_{\rm T}\cdot t)= q_1(t)\cdot \big[ 1 + \cos (2 \omega_{\rm T}\cdot t) \big] - q_2(t)\cdot \sin (2 \omega_{\rm T}\cdot t) \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- Thus, by limiting to frequencies $|f| < f_{\rm T}$ , we obtain in the upper and lower branches, respectively:

- $$v_1(t) = q_1(t),\hspace{0.3cm} v_2(t) = q_2(t)\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- When there is a phase offset $Δϕ_{\rm T}$ between the transmitted and received carrier signals, in addition to attenuation of the intended participant, crosstalk from the second participant occurs, resulting in nonlinear distortion:

- $$v_1(t) = \alpha_{11} \cdot q_1(t)+ \alpha_{12} \cdot q_2(t) \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.3cm} v_2(t) = \alpha_{21} \cdot q_1(t)+ \alpha_{22} \cdot q_2(t)$$

- $$\Rightarrow\hspace{0.3cm}\alpha_{11} = \alpha_{22} = \cos(\Delta \phi_{\rm T}) \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.3cm} \alpha_{12} = -\alpha_{21} = \sin(\Delta \phi_{\rm T}) \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

Incoherent (non-coherent) Demodulation

Demodulators can be classified in the following way:

$\text{Definition:}$ A demodulator is said to be coherent, if in addition to the required frequency synchronization, it requires accurate information about the phase of the transmit-side carrier signal $z(t)$ to reconstruct the message signal.

If this phase information is not required, the demodulator is said to be an incoherent demodulator.

An example of an incoherent (or non-coherent) demodulator is the envelope demodulator.

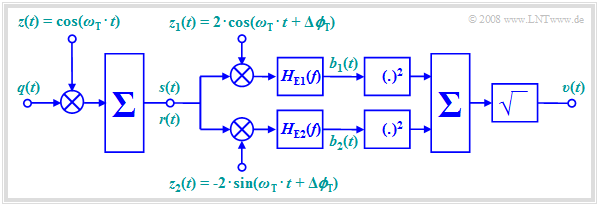

$\text{Example 2:}$ A second example is shown in the following block diagram. In contrast to quadrature amplitude modulation, here the orthogonality between cosine and sine functions is not used for the simultaneous transmission of a second source signal, but rather to simplify the receiver-side device.

It should be further noted regarding this arrangement:

- The receiver-side carrier signals can have an arbitrary and also time-dependent phase offset $Δϕ_{\rm T}$ with respect to the carrier signals at the transmitter, as long as the phase difference between the two branches remains exactly $90^\circ$ .

- For the signals in the upper and lower branches – after the multiplier and low-pass filtering, respectively – it holds:

- $$b_1(t) = \cos(\Delta \phi_{\rm T}) \cdot q(t), $$

- $$b_2(t) = -\sin(\Delta \phi_{\rm T}) \cdot q(t).$$

- This ensures that the sink signal $v(t)$ matches the source signal $q(t)$ , at least in magnitude, regardless of the phase offset $Δϕ_{\rm T}$ :

- $$v(t) = \sqrt{ b_1^2(t) + b_2^2(t)} = \sqrt{ q^2(t) } = \vert q(t) \vert \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- A prerequisite for operability – that is, for the result $v(t) = q(t)$ – is that at all times $q(t) ≥ 0$ . In an analog message system, this fact could be enforced using the "DSB-AM with carrier" modulation method, for example.

- This form of non-coherent demodulation - or modifications of it - is mainly applied in some digital modulation methods, which are discussed in detail in the fourth chapter of this book.

Exercises for the chapter

Exercise 2.12: Non-coherent Demodulation

Exercise 2.13: Quadrature Amplitude Modulation (QAM)

References

- ↑ Mäusl, R.: Analoge Modulationsverfahren. Heidelberg: Dr. Hüthig, 1988.