Difference between revisions of "Channel Coding/Algebraic and Polynomial Description"

| (106 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Header | {{Header | ||

| − | |Untermenü= | + | |Untermenü=Convolutional Codes and Their Decoding |

| − | |Vorherige Seite= | + | |Vorherige Seite=Basics of Convolutional Coding |

| − | |Nächste Seite= | + | |Nächste Seite=Code Description with State and Trellis Diagram |

}} | }} | ||

| − | == | + | == Division of the generator matrix into partial matrices == |

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | + | Following the discussion in the earlier section [[Channel_Coding/General_Description_of_Linear_Block_Codes#Linear_codes_and_cyclic_codes| "Linear Codes and Cyclic Codes"]] the code word $\underline{x}$ of a linear block code can be determined from the information word $\underline{u}$ and the generator matrix $\mathbf{G}$ in a simple way: $\underline{x} = \underline{u} \cdot { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}$. The following holds: | |

| + | # The vectors $\underline{u}$ and $\underline{x}$ have length $k$ $($bit count of an info word$)$ resp. $n$ $($bit count of a code word$)$ and $\mathbf{G}$ has dimension $k × n$ $(k$ rows and $n$ columns$)$.<br> | ||

| + | # In convolutional coding, on the other hand $\underline{u}$ and $\underline{x}$ denote sequences with $k\hspace{0.05cm}' → ∞$ and $n\hspace{0.05cm}' → ∞$. | ||

| + | # Therefore, the generator matrix $\mathbf{G}$ will also be infinitely extended in both directions.<br><br> | ||

| − | + | In preparation for the introduction of the generator matrix $\mathbf{G}$ in the next section, | |

| + | *we define $m + 1$ "partial matrices", each with $k$ rows and $n$ columns, which we denote by $\mathbf{G}_l$ | ||

| − | + | *where $0 ≤ l ≤ m$ holds.<br> | |

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | {{BlaueBox|TEXT= | |

| + | $\text{Definition:}$ The »'''partial matrix'''« $\mathbf{G}_l$ describes the following fact: | ||

| + | *If the matrix element $\mathbf{G}_l(\kappa, j) = 1$, this says that the code bit $x_i^{(j)}$ is influenced by the information bit $u_{i-l}^{(\kappa)}$. | ||

| − | { | + | *Otherwise, this matrix element is $\mathbf{G}_l(\kappa, j) =0$.}}<br> |

| − | + | This definition will now be illustrated by an example. | |

| − | {{ | + | {{GraueBox|TEXT= |

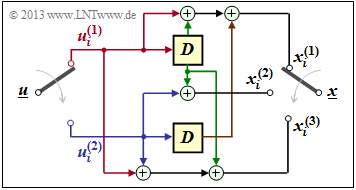

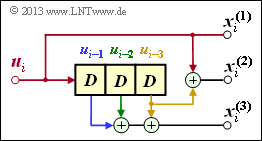

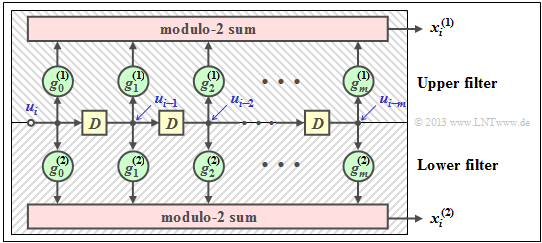

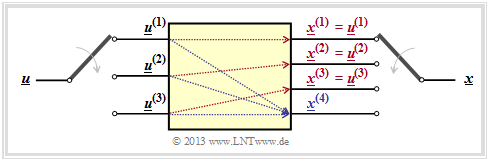

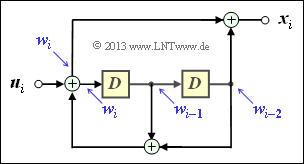

| − | [[File:P ID2600 KC T 3 1 S4 v1.png| | + | $\text{Example 1:}$ |

| + | We again consider the convolutional encoder according to the diagram with the following code bits: | ||

| + | [[File:P ID2600 KC T 3 1 S4 v1.png|right|frame|Convolutional encoder with $k = 2, \ n = 3, \ m = 1$]] | ||

| − | :<math>x_i^{(1)} | + | ::<math>x_i^{(1)} = u_{i}^{(1)} + u_{i-1}^{(1)}+ u_{i-1}^{(2)} \hspace{0.05cm},</math> |

| − | :<math>x_i^{(2)} | + | ::<math>x_i^{(2)} = u_{i}^{(2)} + u_{i-1}^{(1)} \hspace{0.05cm},</math> |

| − | :<math>x_i^{(3)} | + | ::<math>x_i^{(3)} = u_{i}^{(1)} + u_{i}^{(2)}+ u_{i-1}^{(1)} \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> |

| − | + | Because of the memory $m = 1$ this encoder is fully characterized by the partial matrices $\mathbf{G}_0$ and $\mathbf{G}_1$ : | |

| − | :<math>{ \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_0 = | + | ::<math>{ \boldsymbol{\rm G} }_0 = |

\begin{pmatrix} | \begin{pmatrix} | ||

1 & 0 & 1\\ | 1 & 0 & 1\\ | ||

0 & 1 & 1 | 0 & 1 & 1 | ||

\end{pmatrix} \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.5cm} | \end{pmatrix} \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.5cm} | ||

| − | { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_1 = \begin{pmatrix} | + | { \boldsymbol{\rm G} }_1 = \begin{pmatrix} |

1 & 1 & 1\\ | 1 & 1 & 1\\ | ||

1 & 0 & 0 | 1 & 0 & 0 | ||

\end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | ||

| − | + | These matrices are to be interpreted as follows: | |

| − | * | + | *First row of $\mathbf{G}_0$, red arrows: $\hspace{1.3cm}u_i^{(1)}$ affects both $x_i^{(1)}$ and $x_i^{(3)}$, but not $x_i^{(2)}$.<br> |

| − | * | + | *Second row of $\mathbf{G}_0$, blue arrows: $\hspace{0.6cm}u_i^{(2)}$ affects $x_i^{(2)}$ and $x_i^{(3)}$, but not $x_i^{(1)}$.<br> |

| − | * | + | *First row of $\mathbf{G}_1$, green arrows: $\hspace{0.9cm}u_{i-1}^{(1)}$ affects all three encoder outputs.<br> |

| − | * | + | *Second row of $\mathbf{G}_1$, brown arrow: $\hspace{0.45cm}u_{i-1}^{(2)}$ affects only $x_i^{(1)}$.}}<br> |

| − | == | + | == Generator matrix of a convolutional encoder with memory $m$ == |

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | + | The $n$ code bits at time $i$ can be expressed with the partial matrices $\mathbf{G}_0, \hspace{0.05cm} \text{...} \hspace{0.05cm} , \mathbf{G}_m$ as follows: | |

| − | :<math>\underline{x}_i = \sum_{l = 0}^{m} \hspace{0.15cm}\underline{u}_{i-l} \cdot { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_l = | + | ::<math>\underline{x}_i = \sum_{l = 0}^{m} \hspace{0.15cm}\underline{u}_{i-l} \cdot { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_l = |

| − | \underline{u}_{i} \cdot { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_0 + \underline{u}_{i-1} \cdot { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_1 + ... + \underline{u}_{i-m} \cdot { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_m | + | \underline{u}_{i} \cdot { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_0 + \underline{u}_{i-1} \cdot { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_1 +\hspace{0.05cm} \text{...} \hspace{0.05cm} + \underline{u}_{i-m} \cdot { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_m |

\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | ||

| − | + | *The following vectorial quantities must be taken into account: | |

| − | :<math>\underline{\it u}_i = \left ( u_i^{(1)}, u_i^{(2)}, \hspace{0.05cm}... \hspace{0.1cm}, u_i^{(k)}\right )\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.5cm} | + | ::<math>\underline{\it u}_i = \left ( u_i^{(1)}, u_i^{(2)}, \hspace{0.05cm}\text{...} \hspace{0.1cm}, u_i^{(k)}\right )\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.5cm} |

| − | \underline{\it x}_i = \left ( x_i^{(1)}, x_i^{(2)}, \hspace{0.05cm}... \hspace{0.1cm}, x_i^{(n)}\right )\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | + | \underline{\it x}_i = \left ( x_i^{(1)}, x_i^{(2)}, \hspace{0.05cm}\text{...} \hspace{0.1cm}, x_i^{(n)}\right )\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> |

| − | + | *Considering the sequences | |

| − | :<math>\underline{\it u} = \big( \underline{\it u}_1\hspace{0.05cm}, \underline{\it u}_2\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.05cm}... \hspace{0.1cm}, \underline{\it u}_i\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.05cm}... \hspace{0.1cm} \big)\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.5cm} | + | ::<math>\underline{\it u} = \big( \underline{\it u}_1\hspace{0.05cm}, \underline{\it u}_2\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.05cm}\text{...} \hspace{0.1cm}, \underline{\it u}_i\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.05cm}\text{...} \hspace{0.1cm} \big)\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.5cm} |

| − | \underline{\it x} = \big( \underline{\it x}_1\hspace{0.05cm}, \underline{\it x}_2\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.05cm}... \hspace{0.1cm}, \underline{\it x}_i\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.05cm}... \hspace{0.1cm} \big)\hspace{0.05cm},</math> | + | \underline{\it x} = \big( \underline{\it x}_1\hspace{0.05cm}, \underline{\it x}_2\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.05cm}\text{...} \hspace{0.1cm}, \underline{\it x}_i\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.05cm}\text{...} \hspace{0.1cm} \big)\hspace{0.05cm},</math> |

| − | + | :starting at $i = 1$ and extending in time to infinity, this relation can be expressed by the matrix equation $\underline{x} = \underline{u} \cdot \mathbf{G}$. Here, holds for the generator matrix: | |

| − | :<math>{ \boldsymbol{\rm G}}=\begin{pmatrix} | + | ::<math>{ \boldsymbol{\rm G}}=\begin{pmatrix} |

{ \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_0 & { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_1 & { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_2 & \cdots & { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_m & & & \\ | { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_0 & { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_1 & { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_2 & \cdots & { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_m & & & \\ | ||

& { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_0 & { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_1 & { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_2 & \cdots & { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_m & &\\ | & { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_0 & { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_1 & { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_2 & \cdots & { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_m & &\\ | ||

| Line 78: | Line 84: | ||

\end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | ||

| − | + | *From this equation one immediately recognizes the memory $m$ of the convolutional code. | |

| − | + | *The parameters $k$ and $n$ are not directly readable. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | * However, they are determined by the number of rows and columns of the partial matrices $\mathbf{G}_l$.<br> | |

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | {{GraueBox|TEXT= | |

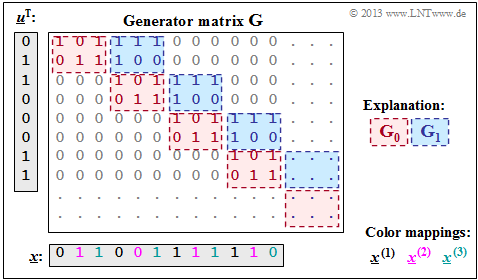

| + | $\text{Example 2:}$ | ||

| + | With the two matrices $\mathbf{G}_0$ and $\mathbf{G}_1$ – see [[Channel_Coding/Algebraic_and_Polynomial_Description#Division_of_the_generator_matrix_into_partial_matrices| $\text{Example 1}$]] – the matrix sketched on the right $\mathbf{G}$ is obtained. | ||

| + | [[File:EN_KC_T_3_2_S2.png|right|frame|Generator matrix of a convolutional code]] | ||

| − | : | + | It should be noted: |

| − | + | *The generator matrix $\mathbf{G}$ actually extends downwards and to the right to infinity. Explicitly shown, however, are only eight rows and twelve columns. | |

| − | == | + | *For the temporal information sequence $\underline{u} = (0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1)$ the drawn matrix part is sufficient. The encoded sequence is then: |

| + | :$$\underline{x} = (0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0).$$ | ||

| + | |||

| + | *On the basis of the label colors, the $n = 3$ code word strings can be read. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *We got the same result $($in a different way$)$ in the [[Channel_Coding/Basics_of_Convolutional_Coding#Convolutional_encoder_with_two_inputs| $\text{Example 4}$]] at the end of the last chapter: | ||

| + | :$$\underline{\it x}^{(1)} = (0\hspace{0.05cm}, 0\hspace{0.05cm}, 1\hspace{0.05cm}, 1) \hspace{0.05cm},$$ | ||

| + | :$$\underline{\it x}^{(2)} = (1\hspace{0.05cm}, 0\hspace{0.05cm},1\hspace{0.05cm}, 1) \hspace{0.05cm},$$ | ||

| + | :$$ \underline{\it x}^{(3)} = (1\hspace{0.05cm}, 1\hspace{0.05cm}, 1\hspace{0.05cm}, 0) \hspace{0.05cm}.$$}}<br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Generator matrix for convolutional encoder of rate $1/n$ == | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

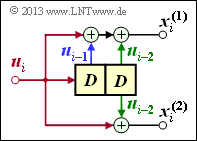

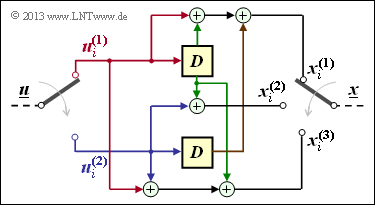

| − | + | We now consider the special case $k = 1$, | |

| − | + | *on the one hand for reasons of simplest possible representation, | |

| − | + | ||

| + | *but also because convolutional encoders of rate $1/n$ have great importance for practice.<br><br> | ||

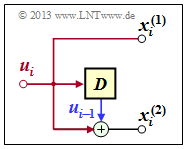

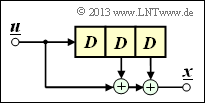

| − | < | + | [[File:KC_T_3_2_S3a_neuv3.png|right|frame|Convolutional encoder<br>$(k = 1, \ n = 2, \ m = 1)$]] |

| + | <b>Convolutional encoder with $k = 1, \ n = 2, \ m = 1$</b><br> | ||

| − | + | *From the adjacent sketch can be derived: | |

| − | : | + | :$${ \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_0=\begin{pmatrix} |

1 & 1 | 1 & 1 | ||

\end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.3cm} | \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.3cm} | ||

{ \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_1=\begin{pmatrix} | { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_1=\begin{pmatrix} | ||

0 & 1 | 0 & 1 | ||

| − | \end{pmatrix} | + | \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.3cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}$$ |

| − | + | *Thus, the resulting generator matrix is: | |

| − | + | :$${ \boldsymbol{\rm G}}=\begin{pmatrix} | |

| − | |||

11 & 01 & 00 & 00 & 00 & \cdots & \\ | 11 & 01 & 00 & 00 & 00 & \cdots & \\ | ||

00 & 11 & 01 & 00 & 00 & \cdots & \\ | 00 & 11 & 01 & 00 & 00 & \cdots & \\ | ||

| Line 117: | Line 134: | ||

00 & 00 & 00 & 11 & 01 & \cdots & \\ | 00 & 00 & 00 & 11 & 01 & \cdots & \\ | ||

\cdots & \cdots & \cdots & \cdots & \cdots & \cdots | \cdots & \cdots & \cdots & \cdots & \cdots & \cdots | ||

| − | \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm}. | + | \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ |

| − | + | *For the input sequence $\underline{u} = (1, 0, 1, 1)$, the encoded sequence starts with $\underline{x} = (1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, \ \text{...})$. | |

| − | + | *This result is equal to the sum of rows '''1''', '''3''' and '''4''' of the generator matrix.<br><br> | |

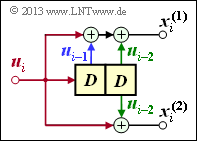

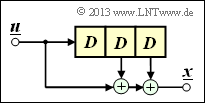

| − | <b> | + | [[File:P ID2603 KC T 3 2 S3b.png|right|frame|Convolutional encoder $(k = 1, \ n = 2, \ m = 2)$]] |

| + | <b>Convolutional encoder with $k = 1, \ n = 2, \ m = 2$</b><br> | ||

| − | + | *Due to the memory order $m = 2$ there are three submatrices here: | |

| − | :<math>{ \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_0=\begin{pmatrix} | + | ::<math>{ \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_0=\begin{pmatrix} |

1 & 1 | 1 & 1 | ||

\end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.3cm} | \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.3cm} | ||

| Line 137: | Line 155: | ||

\end{pmatrix}</math> | \end{pmatrix}</math> | ||

| − | :<math> | + | *Thus, the resulting generator matrix is now: |

| − | + | ||

| + | ::<math> { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}=\begin{pmatrix} | ||

11 & 10 & 11 & 00 & 00 & 00 & \cdots & \\ | 11 & 10 & 11 & 00 & 00 & 00 & \cdots & \\ | ||

00 & 11 & 10 & 11 & 00 & 00 & \cdots & \\ | 00 & 11 & 10 & 11 & 00 & 00 & \cdots & \\ | ||

| Line 146: | Line 165: | ||

\end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | ||

| − | + | *Here the input sequence $\underline{u} = (1, 0, 1, 1)$ leads to the encoded sequence $\underline{x} = (1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, \ \text{...})$.<br><br> | |

| − | [[File:P ID2604 KC T 3 2 S3c.png| | + | [[File:P ID2604 KC T 3 2 S3c.png|right|frame|Convolutional encoder $(k = 1, \ n = 3, \ m = 3)$]] |

| + | <b>Convolutional encoder with $k = 1, \ n = 3, \ m = 3$</b> | ||

| − | + | *Because of $m = 3$ there are now four partial matrices of the respective dimension $1 × 3$: | |

| − | + | ::<math>{ \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_0=\begin{pmatrix} | |

| − | |||

| − | :<math>{ \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_0=\begin{pmatrix} | ||

1 & 1 & 0 | 1 & 1 & 0 | ||

\end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.3cm} | \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.3cm} | ||

{ \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_1=\begin{pmatrix} | { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_1=\begin{pmatrix} | ||

0 & 0 & 1 | 0 & 0 & 1 | ||

| − | \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm}, | + | \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.3cm} |

| − | + | { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_2=\begin{pmatrix} | |

| − | |||

0 & 0 & 1 | 0 & 0 & 1 | ||

\end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.3cm} | \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.3cm} | ||

| Line 168: | Line 185: | ||

\end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | ||

| − | + | *Thus, the resulting generator matrix is: | |

| − | :<math>{ \boldsymbol{\rm G}}=\begin{pmatrix} | + | ::<math>{ \boldsymbol{\rm G}}=\begin{pmatrix} |

110 & 001 & 001 & 011 & 000 & 000 & 000 & \cdots & \\ | 110 & 001 & 001 & 011 & 000 & 000 & 000 & \cdots & \\ | ||

000 & 110 & 001 & 001 & 011 & 000 & 000 & \cdots & \\ | 000 & 110 & 001 & 001 & 011 & 000 & 000 & \cdots & \\ | ||

| Line 176: | Line 193: | ||

000 & 000 & 000 & 110 & 001 & 001 & 011 & \cdots & \\ | 000 & 000 & 000 & 110 & 001 & 001 & 011 & \cdots & \\ | ||

\cdots & \cdots & \cdots & \cdots & \cdots & \cdots & \cdots & \cdots | \cdots & \cdots & \cdots & \cdots & \cdots & \cdots & \cdots & \cdots | ||

| − | \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm} | + | \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> |

| − | + | *One obtains for $\underline{u} = (1, 0, 1, 1)$ the encoded sequence $\underline{x} = (1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, \ \text{...})$.<br> | |

| − | == GF(2) | + | == GF(2) description forms of a digital filter == |

<br> | <br> | ||

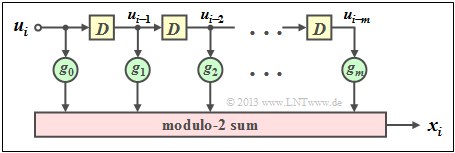

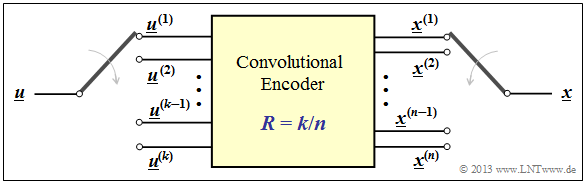

| − | In | + | [[File:EN_KC_T_3_2_S4.png|right|frame|Digital filter in ${\rm GF}(2)$ of order $m$|class=fit]] |

| + | In the chapter [[Channel_Coding/Basics_of_Convolutional_Coding#Rate_1.2F2_convolutional_encoder| "Basics of Convolutional Coding"]] it was already pointed out, | ||

| + | # that a rate $1/n$ convolutional encoder can be realized by several digital filters, | ||

| + | # where the filters operate in parallel with the same input sequence $\underline{u}$ . | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Before we elaborate on this statement, we shall first mention the properties of a digital filter for the Galois field ${\rm GF(2)}$. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The graph is to be interpreted as follows: | ||

| + | *The filter has impulse response $\underline{g} = (g_0,\ g_1,\ g_2, \ \text{...} \ ,\ g_m)$. | ||

| − | + | * For all filter coefficients $($with indices $0 ≤ l ≤ m)$ holds: $g_l ∈ {\rm GF}(2) = \{0, 1\}$.<br> | |

| − | + | *The individual symbols $u_i$ of the input sequence $\underline{u}$ are also binary: $u_i ∈ \{0, 1\}$. | |

| − | * | ||

| − | * | + | *Thus, for the output symbol at times $i ≥ 1$ with addition and multiplication in ${\rm GF(2)}$: |

::<math>x_i = \sum_{l = 0}^{m} g_l \cdot u_{i-l} \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | ::<math>x_i = \sum_{l = 0}^{m} g_l \cdot u_{i-l} \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | ||

| + | *This corresponds to the $($discrete time$)$ »[[Signal_Representation/The_Convolution_Theorem_and_Operation#Convolution_in_the_time_domain|$\rm convolution$]]«, denoted by an asterisk. This can be used to write for the entire output sequence: | ||

| − | + | ::<math>\underline{x} = \underline{u} * \underline{g}\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | |

| − | + | *Major difference compared to the chapter »[[Theory_of_Stochastic_Signals/Digital_Filters|"Digital Filters"]]« in the book "Theory of Stochastic Signals" is the modulo-2 addition $(1 + 1 = 0)$ instead of the conventional addition $(1 + 1 = 2)$.<br><br> | |

| − | + | {{GraueBox|TEXT= | |

| + | $\text{Example 3:}$ | ||

| + | The impulse response of the shown third order digital filter is: $\underline{g} = (1, 0, 1, 1)$. | ||

| + | [[File:P ID2606 KC T 3 2 S4b.png|right|frame|Digital filter with impulse response $(1, 0, 1, 1)$]] | ||

| − | + | *Let the input sequence of this filter be unlimited in time: $\underline{u} = (1, 1, 0, 0, 0, \ \text{ ...})$.<br> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *This gives the $($infinite$)$ initial sequence $\underline{x}$ in the binary Galois field ⇒ ${\rm GF(2)}$: | |

| − | :<math>\underline{x} | + | ::<math>\underline{x} = (\hspace{0.05cm}1,\hspace{0.05cm} 1,\hspace{0.05cm} 0,\hspace{0.05cm} 0,\hspace{0.05cm} 0, \hspace{0.05cm} \text{ ...} \hspace{0.05cm}) * (\hspace{0.05cm}1,\hspace{0.05cm} 0,\hspace{0.05cm} 1,\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm})</math> |

| − | :<math>\hspace{0.3cm} | + | ::<math>\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} \underline{x} =(\hspace{0.05cm}1,\hspace{0.05cm} 0,\hspace{0.05cm} 1,\hspace{0.05cm} 1,\hspace{0.05cm} 0, \hspace{0.05cm}0,\hspace{0.05cm} \text{ ...} \hspace{0.05cm}) |

| − | \oplus (\hspace{0.05cm}0,\hspace{0.05cm}\hspace{0.05cm}1,\hspace{0.05cm} 0,\hspace{0.05cm} 1,\hspace{0.05cm} 1,\hspace{0.05cm}0, \hspace{0.05cm} . ... \hspace{0.05cm}) | + | \oplus (\hspace{0.05cm}0,\hspace{0.05cm}\hspace{0.05cm}1,\hspace{0.05cm} 0,\hspace{0.05cm} 1,\hspace{0.05cm} 1,\hspace{0.05cm}0, \hspace{0.05cm} \hspace{0.05cm} \text{ ...}\hspace{0.05cm}) |

| − | = (\hspace{0.05cm}1,\hspace{0.05cm}\hspace{0.05cm}1,\hspace{0.05cm} 1,\hspace{0.05cm} 0,\hspace{0.05cm} 1,\hspace{0.05cm} 0, . ... \hspace{0.05cm}) \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | + | = (\hspace{0.05cm}1,\hspace{0.05cm}\hspace{0.05cm}1,\hspace{0.05cm} 1,\hspace{0.05cm} 0,\hspace{0.05cm} 1,\hspace{0.05cm} 0, \hspace{0.05cm} \text{ ...} \hspace{0.05cm}) \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> |

| − | + | *In the conventional convolution $($for real numbers$)$, on the other hand, the result would have been: | |

| − | :<math>\underline{x}= (\hspace{0.05cm}1,\hspace{0.05cm}\hspace{0.05cm}1,\hspace{0.05cm} 1,\hspace{0.05cm} 2,\hspace{0.05cm} 1,\hspace{0.05cm} 0, . .. | + | ::<math>\underline{x}= (\hspace{0.05cm}1,\hspace{0.05cm}\hspace{0.05cm}1,\hspace{0.05cm} 1,\hspace{0.05cm} 2,\hspace{0.05cm} 1,\hspace{0.05cm} 0, \text{ ...} \hspace{0.05cm}) \hspace{0.05cm}.</math>}}<br> |

| − | + | However, discrete time signals can also be represented by polynomials with respect to a dummy variable.<br> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | {{Definition} | + | {{BlaueBox|TEXT= |

| + | $\text{Definition:}$ The »<b>D–transform</b>« belonging to the discrete time signal $\underline{x} = (x_0, x_1, x_2, \ \text{...}) $ reads: | ||

| − | :<math>X(D) = x_0 + x_1 \cdot D + x_2 \cdot D^2 + \hspace{0.05cm}...\hspace{0.05cm}= \sum_{i = 0}^{\infty} x_i \cdot D^i \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | + | ::<math>X(D) = x_0 + x_1 \cdot D + x_2 \cdot D^2 + \hspace{0.05cm}\text{...}\hspace{0.05cm}= \sum_{i = 0}^{\infty} x_i \cdot D\hspace{0.05cm}^i \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> |

| − | + | *For this particular transformation to an image area, we also use the following notation, where "D" stands for "delay operator": | |

| − | :<math>\underline{x} = (x_0, x_1, x_2,\hspace{0.05cm}...\hspace{0.05cm}) \quad | + | ::<math>\underline{x} = (x_0, x_1, x_2,\hspace{0.05cm}...\hspace{0.05cm}) \quad |

\circ\!\!-\!\!\!-^{\hspace{-0.25cm}D}\!\!\!-\!\!\bullet\quad | \circ\!\!-\!\!\!-^{\hspace{-0.25cm}D}\!\!\!-\!\!\bullet\quad | ||

| − | X(D) = \sum_{i = 0}^{\infty} x_i \cdot D^i \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | + | X(D) = \sum_{i = 0}^{\infty} x_i \cdot D\hspace{0.05cm}^i \hspace{0.05cm}.</math>}}<br> |

| − | + | <u>Note</u>: In the literature, sometimes $x(D)$ is used instead of $X(D)$. However, we write in our learning tutorial all image domain functions ⇒ "spectral domain functions" with capital letters, for example the Fourier transform, the Laplace transform and the D–transform: | |

| − | :<math>x(t) \hspace{0.15cm} | + | ::<math>x(t) \hspace{0.15cm} |

\circ\!\!-\!\!\!-^{\hspace{-0.25cm}}\!\!\!-\!\!\bullet\hspace{0.15cm} | \circ\!\!-\!\!\!-^{\hspace{-0.25cm}}\!\!\!-\!\!\bullet\hspace{0.15cm} | ||

X(f)\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.4cm} x(t) \hspace{0.15cm} | X(f)\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.4cm} x(t) \hspace{0.15cm} | ||

| Line 238: | Line 264: | ||

X(D) \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | X(D) \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | ||

| − | + | We now apply the D–transform also | |

| + | *to the information sequence $\underline{u}$, and | ||

| − | :<math>\underline{u} = (u_0, u_1, u_2,\hspace{0.05cm}...\hspace{0.05cm}) \quad | + | * the impulse response $\underline{g}$. |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Due to the time limit of $\underline{g}$ the upper summation limit at $G(D)$ results in $i = m$:<br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ::<math>\underline{u} = (u_0, u_1, u_2,\hspace{0.05cm}\text{...}\hspace{0.05cm}) \quad | ||

\circ\!\!-\!\!\!-^{\hspace{-0.25cm}D}\!\!\!-\!\!\bullet\quad | \circ\!\!-\!\!\!-^{\hspace{-0.25cm}D}\!\!\!-\!\!\bullet\quad | ||

| − | U(D) = \sum_{i = 0}^{\infty} u_i \cdot D^i \hspace{0.05cm},</math> | + | U(D) = \sum_{i = 0}^{\infty} u_i \cdot D\hspace{0.05cm}^i \hspace{0.05cm},</math> |

| − | :<math>\underline{g} = (g_0, g_1, \hspace{0.05cm}...\hspace{0.05cm}, g_m) \quad | + | ::<math>\underline{g} = (g_0, g_1, \hspace{0.05cm}\text{...}\hspace{0.05cm}, g_m) \quad |

\circ\!\!-\!\!\!-^{\hspace{-0.25cm}D}\!\!\!-\!\!\bullet\quad | \circ\!\!-\!\!\!-^{\hspace{-0.25cm}D}\!\!\!-\!\!\bullet\quad | ||

| − | G(D) = \sum_{i = 0}^{m} g_i \cdot D^i \hspace{0.05cm}.</math | + | G(D) = \sum_{i = 0}^{m} g_i \cdot D\hspace{0.05cm}^i \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> |

| − | {{ | + | {{BlaueBox|TEXT= |

| + | $\text{Theorem:}$ As with all spectral transformations, the »<b>multiplication</b>« applies to the D–transform in the image domain, since the $($discrete$)$ time functions $\underline{u}$ and $\underline{g}$ are interconnected by the »<b>convolution</b>«: | ||

| − | :<math>\underline{x} = \underline{u} * \underline{g} \quad | + | ::<math>\underline{x} = \underline{u} * \underline{g} \quad |

\circ\!\!-\!\!\!-^{\hspace{-0.25cm}D}\!\!\!-\!\!\bullet\quad | \circ\!\!-\!\!\!-^{\hspace{-0.25cm}D}\!\!\!-\!\!\bullet\quad | ||

X(D) = U(D) \cdot G(D) \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | X(D) = U(D) \cdot G(D) \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | ||

| − | + | *The $($rather simple$)$ $\rm proof$ of this important result can be found in the specification for [[Aufgaben:Exercise_3.3Z:_Convolution_and_D-Transformation|"Exercise 3.3Z"]]. | |

| − | + | *As in »[[Linear_and_Time_Invariant_Systems/System_Description_in_Frequency_Domain#Frequency_response_.E2.80.93_Transfer_function|$\text{system theory}$]]« commonly, the D–transform $G(D)$ of the impulse response $\underline{g}$ is also called "transfer function".}} | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | :<math>\underline{u} = (\hspace{0.05cm}1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm}...\hspace{0.05cm}) \quad | + | |

| + | {{GraueBox|TEXT= | ||

| + | [[File:P ID2607 KC T 3 2 S4b.png|right|frame|Impulse response $(1, 0, 1, 1)$ of a digital filter]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | $\text{Example 4:}$ We consider again the discrete time signals | ||

| + | ::<math>\underline{u} = (\hspace{0.05cm}1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm}\text{...}\hspace{0.05cm}) \quad | ||

\circ\!\!-\!\!\!-^{\hspace{-0.25cm}D}\!\!\!-\!\!\bullet\quad | \circ\!\!-\!\!\!-^{\hspace{-0.25cm}D}\!\!\!-\!\!\bullet\quad | ||

U(D) = 1+ D \hspace{0.05cm},</math> | U(D) = 1+ D \hspace{0.05cm},</math> | ||

| − | :<math>\underline{g} = (\hspace{0.05cm}1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm}) \quad | + | ::<math>\underline{g} = (\hspace{0.05cm}1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm}) \quad |

\circ\!\!-\!\!\!-^{\hspace{-0.25cm}D}\!\!\!-\!\!\bullet\quad | \circ\!\!-\!\!\!-^{\hspace{-0.25cm}D}\!\!\!-\!\!\bullet\quad | ||

G(D) = 1+ D^2 + D^3 \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | G(D) = 1+ D^2 + D^3 \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | ||

| − | + | *As in $\text{Example 3}$ $($in this section above$)$, you get also on this solution path: | |

| − | :<math>X(D) | + | ::<math>X(D) = U(D) \cdot G(D) = (1+D) \cdot (1+ D^2 + D^3) </math> |

| − | :<math>\ | + | ::<math>\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} X(D) = 1+ D^2 + D^3 +D + D^3 + D^4 = 1+ D + D^2 + D^4 \hspace{0.3cm} |

| + | \Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} \underline{x} = (\hspace{0.05cm}1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm}, \text{...} \hspace{0.05cm}) \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | ||

| − | : | + | *Multiplication by the "delay operator" $D$ in the image domain corresponds to a shift of one place to the right in the time domain: |

| − | + | ::<math>W(D) = D \cdot X(D) \quad | |

| − | |||

| − | :<math>W(D) = D \cdot X(D) \quad | ||

\bullet\!\!-\!\!\!-^{\hspace{-0.25cm}D}\!\!\!-\!\!\circ\quad | \bullet\!\!-\!\!\!-^{\hspace{-0.25cm}D}\!\!\!-\!\!\circ\quad | ||

| − | \underline{w} = (\hspace{0.05cm}0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm}1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm}, ... \hspace{0.05cm}) \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | + | \underline{w} = (\hspace{0.05cm}0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm}1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm}, \text{...} \hspace{0.05cm}) \hspace{0.05cm}.</math>}}<br> |

| − | == | + | == Application of the D–transform to rate $1/n$ convolution encoders == |

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | + | We now apply the results of the last section to a convolutional encoder, restricting ourselves for the moment to the special case $k = 1$. | |

| + | *Such a $(n, \ k = 1)$ convolutional code can be realized with $n$ digital filters operating in parallel on the same information sequence $\underline{u}$. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *The graph shows the arrangement for the code parameter $n = 2$ ⇒ code rate $R = 1/2$.<br> | ||

| − | [[File: | + | [[File:EN_KC_T_3_2_S5.png|right|frame|Two filters working in parallel, each with order $m$|class=fit]] |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The following equations apply equally to both filters, setting $j = 1$ for the upper filter and $j = 2$ for the lower filter: | |

| + | *The »<b>impulse responses</b>« of the two filters result in | ||

| − | + | ::<math>\underline{g}^{(j)} = (g_0^{(j)}, g_1^{(j)}, \hspace{0.05cm}\text{...}\hspace{0.05cm}, g_m^{(j)}\hspace{0.01cm}) \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}{\rm with }\hspace{0.15cm} j \in \{1,2\}\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | |

| − | + | *The two »<b>output sequences</b>« are as follows, considering that both filters operate on the same input sequence $\underline{u} = (u_0, u_1, u_2, \hspace{0.05cm} \text{...})$ : | |

| − | : | + | ::<math>\underline{x}^{(j)} = (x_0^{(j)}, x_1^{(j)}, x_2^{(j)}, \hspace{0.05cm}\text{...}\hspace{0.05cm}) = \underline{u} \cdot \underline{g}^{(j)} \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}{\rm with }\hspace{0.15cm} j \in \{1,2\}\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> |

| − | * | + | *For the »<b>D–transform</b>« of the output sequences: |

| − | ::<math>X^{(j)}(D) = U(D) \cdot G^{(j)}(D) \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}{\rm | + | ::<math>X^{(j)}(D) = U(D) \cdot G^{(j)}(D) \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}{\rm with }\hspace{0.15cm} j \in \{1,2\}\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> |

| − | + | In order to represent this fact more compactly, we now define the following vectorial quantities of a convolutional code of rate $1/n$: | |

| − | = | + | {{BlaueBox|TEXT= |

| − | < | + | $\text{Definition:}$ The »<b>D– transfer functions</b>« of the $n$ parallel arranged digital filters are combined in the vector $\underline{G}(D)$: |

| − | |||

| − | {{ | + | ::<math>\underline{G}(D) = \left ( G^{(1)}(D), G^{(2)}(D), \hspace{0.05cm}\text{...}\hspace{0.1cm}, G^{(n)} (D) \right )\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> |

| − | + | *The vector $\underline{X}(D)$ contains the D–transform of $n$ encoded sequences $\underline{x}^{(1)}, \underline{x}^{(2)}, \ \text{...} \ , \underline{x}^{(n)}$: | |

| − | + | ::<math>\underline{X}(D) = \left ( X^{(1)}(D), X^{(2)}(D), \hspace{0.05cm}\text{...}\hspace{0.1cm}, X^{(n)} (D) \right )\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | |

| − | : | + | *This gives the following vector equation: |

| − | + | ::<math>\underline{X}(D) = U(D) \cdot \underline{G}(D)\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | |

| − | + | *$U(D)$ is not a vector quantity here because of the code parameter $k = 1$.}}<br> | |

| − | + | {{GraueBox|TEXT= | |

| + | $\text{Example 5:}$ | ||

| + | We consider the convolutional encoder with code parameters $n = 2, \ k = 1, \ m = 2$. For this one holds: | ||

| + | [[File:P ID2609 KC T 3 2 S5b.png|right|frame|Convolutional encoder $(n = 2, \ k = 1,\ m = 2)$]] | ||

| − | + | ::<math>\underline{g}^{(1)} =(\hspace{0.05cm}1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm}) \quad \circ\!\!-\!\!\!-^{\hspace{-0.25cm}D}\!\!\!-\!\!\bullet\quad | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | :<math>\underline{g}^{(1)} | ||

G(D) = 1+ D + D^2 \hspace{0.05cm},</math> | G(D) = 1+ D + D^2 \hspace{0.05cm},</math> | ||

| − | :<math>\underline{g}^{(2)} | + | ::<math>\underline{g}^{(2)}= (\hspace{0.05cm}1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm}) \quad \circ\!\!-\!\!\!-^{\hspace{-0.25cm}D}\!\!\!-\!\!\bullet\quad |

G(D) = 1+ D^2 </math> | G(D) = 1+ D^2 </math> | ||

| + | ::<math>\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} \underline{G}(D) = \big ( 1+ D + D^2 \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.1cm}1+ D^2 \big )\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | ||

| − | + | *Let the information sequence be $\underline{u} = (1, 0, 1, 1)$ ⇒ D–transform $U(D) = 1 + D^2 + D^3$. This gives: | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | :<math>\underline{X}(D) = \left ( X^{(1)}(D),\hspace{0.1cm} X^{(2)}(D) \right ) = U(D) \cdot \underline{G}(D) \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}</math> | + | ::<math>\underline{X}(D) = \left ( X^{(1)}(D),\hspace{0.1cm} X^{(2)}(D) \right ) = U(D) \cdot \underline{G}(D) \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}</math> |

| − | + | :where | |

| − | :<math>{X}^{(1)}(D) | + | ::<math>{X}^{(1)}(D) = (1+ D^2 + D^3) \cdot (1+ D + D^2)=1+ D + D^2 + D^2 + D^3 + D^4 + D^3 + D^4 + D^5 = 1+ D + D^5</math> |

| − | |||

| − | :<math>\Rightarrow \underline{x}^{(1)} = (\hspace{0.05cm}1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm}1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.05cm} ... \hspace{0.05cm} \hspace{0.05cm}) \hspace{0.05cm},</math> | + | ::<math>\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} \underline{x}^{(1)} = (\hspace{0.05cm}1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm}1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.05cm} \text{...} \hspace{0.05cm} \hspace{0.05cm}) \hspace{0.05cm},</math> |

| − | :<math>{X}^{(2)}(D) | + | ::<math>{X}^{(2)}(D) = (1+ D^2 + D^3) \cdot (1+ D^2)=1+ D^2 + D^2 + D^4 + D^3 + D^5 = 1+ D^3 + D^4 + D^5</math> |

| − | |||

| − | :<math>\Rightarrow \underline{x}^{(2)} = (\hspace{0.05cm}1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm}0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.05cm} ... \hspace{0.05cm} \hspace{0.05cm}) \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | + | ::<math>\Rightarrow \underline{x}^{(2)} = (\hspace{0.05cm}1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm}0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.05cm} \text{...} \hspace{0.05cm} \hspace{0.05cm}) \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> |

| − | + | *We got the same result in [[Aufgaben:Exercise_3.1Z:_Convolution_Codes_of_Rate_1/2|"Exercise 3.1Z"]] on other way. After multiplexing the two strands, you get again: | |

| + | :$$\underline{x} = (11, 10, 00, 01, 01, 11, 00, 00, \hspace{0.05cm} \text{...} \hspace{0.05cm}).$$}}<br> | ||

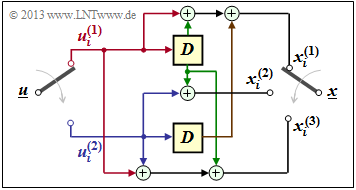

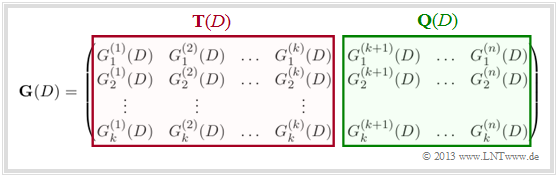

| − | == | + | == Transfer Function Matrix == |

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | + | We have seen that a convolutional code of rate $1/n$ can be most compactly described as a vector equation in the D–transformed domain: | |

| − | + | [[File:EN_KC_T_3_2_S6.png|right|frame|General $(n, \ k)$ convolutional encoder |class=fit]] | |

| − | : | + | |

| + | :$$\underline{X}(D) = U(D) \cdot \underline{G}(D).$$ | ||

| − | + | Now we extend the result to convolutional encoders with more than one input ⇒ $k ≥ 2$ $($see graph$)$.<br> | |

| − | + | In order to map a convolutional code of rate $k/n$ in the D–domain, the dimension of the above vector equation must be increased with respect to input and transfer function: | |

| − | + | ::<math>\underline{X}(D) = \underline{U}(D) \cdot { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}(D)\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | |

| − | : | + | This requires the following measures: |

| + | *From the scalar function $U(D)$ we get the vector | ||

| + | :$$\underline{U}(D) = (U^{(1)}(D), \ U^{(2)}(D), \hspace{0.05cm} \text{...} \hspace{0.05cm} , \ U^{(k)}(D)).$$ | ||

| − | + | *From the vector $\underline{G}(D)$ we get the $k × n$ transfer function matrix $($or "polynomial generator matrix"$)$ $\mathbf{G}(D)$ : | |

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

::<math>{\boldsymbol{\rm G}}(D)=\begin{pmatrix} | ::<math>{\boldsymbol{\rm G}}(D)=\begin{pmatrix} | ||

| − | G_1^{(1)}(D) & G_1^{(2)}(D) & \ | + | G_1^{(1)}(D) & G_1^{(2)}(D) & \hspace{0.05cm} \text{...} \hspace{0.05cm} & G_1^{(n)}(D)\\ |

| − | G_2^{(1)}(D) & G_2^{(2)}(D) & \ | + | G_2^{(1)}(D) & G_2^{(2)}(D) & \hspace{0.05cm} \text{...} \hspace{0.05cm} & G_2^{(n)}(D)\\ |

\vdots & \vdots & & \vdots\\ | \vdots & \vdots & & \vdots\\ | ||

| − | G_k^{(1)}(D) & G_k^{(2)}(D) & \ | + | G_k^{(1)}(D) & G_k^{(2)}(D) & \hspace{0.05cm} \text{...} \hspace{0.05cm} & G_k^{(n)}(D) |

\end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | ||

| − | * | + | *Each of the $k \cdot n$ matrix elements $G_i^{(j)}(D)$ with $1 ≤ i ≤ k,\ 1 ≤ j ≤ n$ is a polynomial over the dummy variable $D$ in the Galois field ${\rm GF}(2)$, maximal of degree $m$, where $m$ denotes the memory.<br> |

| − | * | + | *For the above transfer function matrix, using the [[Channel_Coding/Algebraic_and_Polynomial_Description#Division_of_the_generator_matrix_into_partial_matrices| »$\text{partial matrices}$«]] $\mathbf{G}_0, \ \text{...} \ , \mathbf{G}_m$ also be written $($as index we use again $l)$: |

::<math>{\boldsymbol{\rm G}}(D) = \sum_{l = 0}^{m} {\boldsymbol{\rm G}}_l \cdot D\hspace{0.03cm}^l | ::<math>{\boldsymbol{\rm G}}(D) = \sum_{l = 0}^{m} {\boldsymbol{\rm G}}_l \cdot D\hspace{0.03cm}^l | ||

| − | = {\boldsymbol{\rm G}}_0 + {\boldsymbol{\rm G}}_1 \cdot D + {\boldsymbol{\rm G}}_2 \cdot D^2 + ... \hspace{0.05cm}+ {\boldsymbol{\rm G}}_m \cdot D\hspace{0.03cm}^m | + | = {\boldsymbol{\rm G}}_0 + {\boldsymbol{\rm G}}_1 \cdot D + {\boldsymbol{\rm G}}_2 \cdot D^2 + \hspace{0.05cm} \text{...} \hspace{0.05cm}+ {\boldsymbol{\rm G}}_m \cdot D\hspace{0.03cm}^m |

\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | ||

| − | + | {{GraueBox|TEXT= | |

| + | $\text{Example 6:}$ | ||

| + | We consider the $(n = 3, \ k = 2, \ m = 1)$ convolutional encoder whose partial matrices have already been determined in the [[Channel_Coding/Algebraic_and_Polynomial_Description#Division_of_the_generator_matrix_into_partial_matrices| $\text{Example 1}$]] as follows: | ||

| + | [[File:P ID2617 KC T 3 1 S4 v1.png|right|frame|Convolutional encoder with $k = 2, \ n = 3, \ m = 1$]] | ||

| − | + | ::<math>{ \boldsymbol{\rm G} }_0 = | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | :<math>{ \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_0 = | ||

\begin{pmatrix} | \begin{pmatrix} | ||

1 & 0 & 1\\ | 1 & 0 & 1\\ | ||

0 & 1 & 1 | 0 & 1 & 1 | ||

| − | \end{pmatrix} \hspace{0.05cm}, \ | + | \end{pmatrix} \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.5cm} |

| − | { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_1 = \begin{pmatrix} | + | { \boldsymbol{\rm G} }_1 = \begin{pmatrix} |

1 & 1 & 1\\ | 1 & 1 & 1\\ | ||

1 & 0 & 0 | 1 & 0 & 0 | ||

\end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | ||

| − | + | *Because of $m = 1$ no partial matrices exist for $l ≥ 2$. Thus the transfer function matrix is: | |

| − | :<math>{\boldsymbol{\rm G}}(D) = {\boldsymbol{\rm G}}_0 + {\boldsymbol{\rm G}}_1 \cdot D = | + | ::<math>{\boldsymbol{\rm G} }(D) = {\boldsymbol{\rm G} }_0 + {\boldsymbol{\rm G} }_1 \cdot D = |

\begin{pmatrix} | \begin{pmatrix} | ||

1+D & D & 1+D\\ | 1+D & D & 1+D\\ | ||

| Line 411: | Line 443: | ||

\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | ||

| − | + | *Let the $($time limited$)$ information sequence be $\underline{u} = (0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1)$, from which the two input sequences are as follows: | |

| − | :<math>\underline{u}^{(1)} | + | ::<math>\underline{u}^{(1)} = (\hspace{0.05cm}0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm}1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm}) \quad \circ\!\!-\!\!\!-^{\hspace{-0.25cm}D}\!\!\!-\!\!\bullet\quad |

{U}^{(1)}(D) = D + D^3 \hspace{0.05cm},</math> | {U}^{(1)}(D) = D + D^3 \hspace{0.05cm},</math> | ||

| − | :<math>\underline{u}^{(2)} | + | ::<math>\underline{u}^{(2)} = (\hspace{0.05cm}1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm}0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm}) \quad \circ\!\!-\!\!\!-^{\hspace{-0.25cm}D}\!\!\!-\!\!\bullet\quad |

{U}^{(2)}(D) = 1 + D^3 \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | {U}^{(2)}(D) = 1 + D^3 \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | ||

| − | + | *From this follows for the vector of the D–transform at the encoder output: | |

| − | :<math>\underline{X}(D) | + | ::<math>\underline{X}(D) = \big (\hspace{0.05cm} {X}^{(1)}(D)\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.05cm} {X}^{(2)}(D)\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.05cm} {X}^{(3)}(D)\hspace{0.05cm}\big ) = \underline{U}(D) \cdot {\boldsymbol{\rm G} }(D) |

| − | + | \begin{pmatrix} | |

D+D^3 & 1+D^3 | D+D^3 & 1+D^3 | ||

\end{pmatrix} \cdot \begin{pmatrix} | \end{pmatrix} \cdot \begin{pmatrix} | ||

| Line 428: | Line 460: | ||

\end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | ||

| − | + | *This results in the following encoded sequences in the three strands: | |

| − | :<math>{X}^{(1)}(D) | + | ::<math>{X}^{(1)}(D) = (D + D^3) \cdot (1+D) + (1 + D^3) \cdot D =D + D^2 + D^3 + D^4 + D + D^4 = D^2 + D^3</math> |

| − | |||

| − | :<math>\Rightarrow \underline{x}^{(1)} = (\hspace{0.05cm}0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm}0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm}\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm}\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} ... \hspace{0.05cm}) \hspace{0.05cm},</math> | + | :::<math>\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} \underline{x}^{(1)} = (\hspace{0.05cm}0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm}0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm}\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm}\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} \text{...} \hspace{0.05cm}) \hspace{0.05cm},</math> |

| − | :<math>{X}^{(2)}(D) | + | ::<math>{X}^{(2)}(D)= (D + D^3) \cdot D + (1 + D^3) \cdot 1 = D^2 + D^4 + 1 + D^3 = 1+D^2 + D^3 + D^4</math> |

| − | |||

| − | :<math>\Rightarrow \underline{x}^{(2)} = (\hspace{0.05cm}1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm}0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm}\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm}\hspace{0.05cm} ... \hspace{0.05cm}) \hspace{0.05cm},</math> | + | :::<math>\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}\underline{x}^{(2)} = (\hspace{0.05cm}1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm}0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm}\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm}\hspace{0.05cm} \text{...} \hspace{0.05cm}) \hspace{0.05cm},</math> |

| − | :<math>{X}^{(3)}(D) | + | ::<math>{X}^{(3)}(D)=(D + D^3) \cdot (1 + D) + (1 + D^3) \cdot 1 = D + D^2 + D^3+ D^4 + 1 + D^3 = 1+ D + D^2 + D^4</math> |

| − | |||

| − | :<math>\Rightarrow \underline{x}^{(3)} = (\hspace{0.05cm}1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm}1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm}\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm}\hspace{0.05cm} ... \hspace{0.05cm}) \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | + | :::<math>\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}\underline{x}^{(3)} = (\hspace{0.05cm}1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm}1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm}\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm}\hspace{0.05cm} \text{...} \hspace{0.05cm}) \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> |

| − | + | We have already obtained the same results in other ways in previous examples: | |

| − | * | + | * in [[Channel_Coding/Basics_of_Convolutional_Coding#Convolutional_encoder_with_two_inputs|$\text{Example 4}$]] of the chapter "Basics of Convolutional Coding",<br> |

| − | * | + | *in [[Channel_Coding/Algebraic_and_Polynomial_Description#Generator_matrix_of_a_convolutional_encoder_with_memory_.7F.27.22.60UNIQ-MathJax64-QINU.60.22.27.7F| $\text{Example 2}$]] of the current chapter.}}<br> |

| − | == | + | == Systematic convolutional codes == |

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | + | Polynomial representation using the transfer function matrix $\mathbf{G}(D)$ provides insight into the structure of a convolutional code. | |

| + | [[File:P ID2611 KC T 3 2 S7 v2.png|right|frame|Systematic convolutional code with $k = 3, \ n = 4$|class=fit]] | ||

| − | [[ | + | *This $k × n$ matrix is used to recognize whether it is a [[Channel_Coding/General_Description_of_Linear_Block_Codes#Systematic_Codes| »$\text{systematic code}$«]]. |

| + | |||

| + | *This refers to a code where the encoded sequences $\underline{x}^{(1)}, \ \text{...} \ , \ \underline{x}^{(k)}$ are identical with the information sequences $\underline{u}^{(1)}, \ \text{...} \ , \ \underline{u}^{(k)}$. | ||

| − | + | *The graph shows an example of a systematic $(n = 4, \ k = 3)$ convolutional code.<br> | |

| − | :<math>{\boldsymbol{\rm G}}(D) = {\boldsymbol{\rm G}}_{\rm sys}(D) = \ | + | |

| + | A systematic $(n, k)$ convolutional code exists whenever the transfer function matrix $($with $k$ rows and $n$ columns$)$ has the following appearance: | ||

| + | |||

| + | ::<math>{\boldsymbol{\rm G}}(D) = {\boldsymbol{\rm G}}_{\rm sys}(D) = \left [ \hspace{0.05cm} {\boldsymbol{\rm I}}_k\hspace{0.05cm} ; \hspace{0.1cm} {\boldsymbol{\rm P}}(D) \hspace{0.05cm}\right ] | ||

\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | ||

| − | + | The following nomenclature is used: | |

| − | + | # $\mathbf{I}_k$ denotes a diagonal unit matrix of dimension $k × k$.<br> | |

| + | # $\mathbf{P}(D)$ is a $k × (n -k)$ matrix, where each matrix element describes a polynomial in $D$.<br><br> | ||

| − | + | {{GraueBox|TEXT= | |

| + | $\text{Example 7:}$ A systematic convolutional code with $n = 3, \ k = 2, \ m = 2$ might have the following transfer function matrix: | ||

| − | + | ::<math>{\boldsymbol{\rm G} }_{\rm sys}(D) = \begin{pmatrix} | |

| − | |||

| − | :<math>{\boldsymbol{\rm G}}_{\rm sys}(D) = \begin{pmatrix} | ||

1 & 0 & 1+D^2\\ | 1 & 0 & 1+D^2\\ | ||

0 & 1 & 1+D | 0 & 1 & 1+D | ||

\end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | ||

| − | + | *In contrast, other systematic convolutional codes with equal $n$ and equal $k$ differ only by the two matrix elements in the last column.}}<br> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | == Equivalent systematic convolutional code == | |

| + | <br> | ||

| + | For every $(n, \ k)$ convolutional code with matrix $\mathbf{G}(D)$ there is an "equivalent systematic code" whose D–matrix we denote by $\mathbf{G}_{\rm sys}(D)$.<br> | ||

| − | + | To get from the transfer function matrix $\mathbf{G}(D)$ to the matrix $\mathbf{G}_{\rm sys}(D)$ of the equivalent systematic convolutional code, proceed as follows according to the diagram: | |

| + | [[File:P ID2622 KC T 3 2 S7 v1.png|right|frame|Subdivision of $\mathbf{G}(D)$ into $\mathbf{T}(D)$ and $\mathbf{Q}(D)$|class=fit]] | ||

| + | *Divide the $k × n$ matrix $\mathbf{G}(D)$ into a square matrix $\mathbf{T}(D)$ with $k$ rows and $k$ columns and denote the remainder by $\mathbf{Q}(D)$. | ||

| − | + | *Then calculate the inverse matrix $\mathbf{T}^{-1}(D)$ to $\mathbf{T}(D)$ and from this the matrix for the equivalent systematic code: | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

::<math>{\boldsymbol{\rm G}}_{\rm sys}(D)= {\boldsymbol{\rm T}}^{-1}(D) \cdot {\boldsymbol{\rm G}}(D) \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | ::<math>{\boldsymbol{\rm G}}_{\rm sys}(D)= {\boldsymbol{\rm T}}^{-1}(D) \cdot {\boldsymbol{\rm G}}(D) \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | ||

| − | * | + | *Since the product $\mathbf{T}^{-1}(D) \cdot \mathbf{T}(D)$ yields the $k × k$ unit matrix $\mathbf{I}_k$ <br>⇒ the transfer function matrix of the equivalent systematic code can be written in the desired form: |

| − | ::<math>{\boldsymbol{\rm G}}_{\rm sys}(D) = \ | + | ::<math>{\boldsymbol{\rm G}}_{\rm sys}(D) = \bigg [ \hspace{0.05cm} {\boldsymbol{\rm I}}_k\hspace{0.05cm} ; \hspace{0.1cm} {\boldsymbol{\rm P}}(D) \hspace{0.05cm}\bigg ] |

| − | \hspace{0.5cm}{\rm | + | \hspace{0.5cm}{\rm with}\hspace{0.5cm} {\boldsymbol{\rm P}}(D)= {\boldsymbol{\rm T}}^{-1}(D) \cdot {\boldsymbol{\rm Q}}(D) \hspace{0.05cm}. |

\hspace{0.05cm}</math> | \hspace{0.05cm}</math> | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{GraueBox|TEXT= |

| − | + | $\text{Example 8:}$ | |

| − | + | The encoder of rate $2/3$ considered often in the last sections is not systematic because e.g. $\underline{x}^{(1)} ≠ \underline{u}^{(1)}, \ \underline{x}^{(2)} ≠ \underline{u}^{(2)}$ holds $($see adjacent graphic$)$.<br> | |

| + | [[File:P ID2613 KC T 3 2 S1 neu.png|right|frame|Convolutional encoder of rate $2/3$]] | ||

| − | + | ⇒ However, this can also be seen from the transfer function matrix: | |

| − | :<math>{\boldsymbol{\rm G}}(D) = \big [ \hspace{0.05cm} {\boldsymbol{\rm T}}(D)\hspace{0.05cm} ; \hspace{0.1cm} {\boldsymbol{\rm Q}}(D) \hspace{0.05cm}\big ]</math> | + | ::<math>{\boldsymbol{\rm G} }(D) = \big [ \hspace{0.05cm} {\boldsymbol{\rm T} }(D)\hspace{0.05cm} ; \hspace{0.1cm} {\boldsymbol{\rm Q} }(D) \hspace{0.05cm}\big ]</math> |

| − | :<math>\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} | + | ::<math>\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} |

| − | {\boldsymbol{\rm T}}(D) = \begin{pmatrix} | + | {\boldsymbol{\rm T} }(D) = \begin{pmatrix} |

1+D & D\\ | 1+D & D\\ | ||

D & 1 | D & 1 | ||

\end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm} | \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm} | ||

| − | {\boldsymbol{\rm Q}}(D) = \begin{pmatrix} | + | {\boldsymbol{\rm Q} }(D) = \begin{pmatrix} |

1+D \\ | 1+D \\ | ||

1 | 1 | ||

\end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | ||

| − | + | *The determinant of $\mathbf{T}(D)$ results in $(1 + D) \cdot 1 + D \cdot D = 1 + D + D^2$ and is nonzero. | |

| + | |||

| + | *Thus, for the inverse of $\mathbf{T}(D)$ can be written $($swapping the diagonal elements!$)$: | ||

| − | :<math>{\boldsymbol{\rm T}}^{-1}(D) = \frac{1}{1+D+D^2} \cdot \begin{pmatrix} | + | ::<math>{\boldsymbol{\rm T} }^{-1}(D) = \frac{1}{1+D+D^2} \cdot \begin{pmatrix} |

1 & D\\ | 1 & D\\ | ||

D & 1+D | D & 1+D | ||

\end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | ||

| − | + | *The product $\mathbf{T}(D) \cdot \mathbf{T}^{–1}(D)$ gives the unit matrix $\mathbf{I}_2$ ⇒ for the third column of $\mathbf{G}_{\rm sys}(D)$ holds: | |

| − | :<math>{\boldsymbol{\rm P}}(D)= {\boldsymbol{\rm T}}^{-1}(D) \cdot {\boldsymbol{\rm Q}}(D) | + | ::<math>{\boldsymbol{\rm P} }(D)= {\boldsymbol{\rm T} }^{-1}(D) \cdot {\boldsymbol{\rm Q} }(D) |

= \frac{1}{1+D+D^2} \cdot \begin{pmatrix} | = \frac{1}{1+D+D^2} \cdot \begin{pmatrix} | ||

1 & D\\ | 1 & D\\ | ||

| Line 532: | Line 568: | ||

\end{pmatrix} </math> | \end{pmatrix} </math> | ||

| − | :<math>\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} {\boldsymbol{\rm P}}(D) | + | ::<math>\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} {\boldsymbol{\rm P} }(D) |

= \frac{1}{1+D+D^2} \cdot \begin{pmatrix} | = \frac{1}{1+D+D^2} \cdot \begin{pmatrix} | ||

(1+D) + D \\ | (1+D) + D \\ | ||

| Line 542: | Line 578: | ||

\end{pmatrix} </math> | \end{pmatrix} </math> | ||

| − | :<math>\Rightarrow \hspace{0.2cm}{\boldsymbol{\rm G}}_{\rm sys}(D) = | + | ::<math>\Rightarrow \hspace{0.2cm}{\boldsymbol{\rm G} }_{\rm sys}(D) = |

\begin{pmatrix} | \begin{pmatrix} | ||

1 & 0 & \frac{1}{1+D+D^2}\\ | 1 & 0 & \frac{1}{1+D+D^2}\\ | ||

0 & 1 &\frac{1+D^2}{1+D+D^2} | 0 & 1 &\frac{1+D^2}{1+D+D^2} | ||

| − | \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm}. </math> | + | \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm}. </math>}} |

| + | |||

| − | + | It remains to be clarified what the filter of such a fractional–rational transfer function looks like.<br> | |

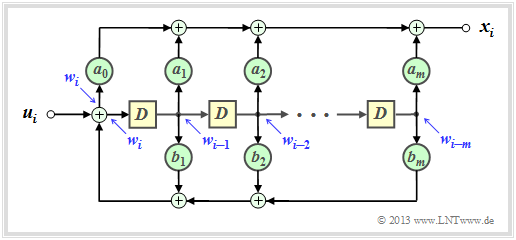

| − | == | + | == Filter structure with fractional–rational transfer function == |

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | + | If a transfer function has the form $G(D) = A(D)/B(D)$, the associated filter is called »<b>recursive</b>«. Given a recursive convolutional encoder with memory $m$, the two polynomials $A(D)$ and $B(D)$ can be written in general terms: | |

| − | + | [[File:P ID2619 KC T 3 2 S8 v1.png|right|frame|Recursive filter for realization of $G(D) = A(D)/B(D)$|class=fit]] | |

| − | :<math>A(D) | + | ::<math>A(D) = \sum_{l = 0}^{m} a_l \cdot D\hspace{0.05cm}^l = a_0 + a_1 \cdot D + a_2 \cdot D^2 +\ \text{...} \ \hspace{0.05cm} + a_m \cdot D\hspace{0.05cm}^m \hspace{0.05cm},</math> |

| − | :<math>B(D) | + | ::<math>B(D) = 1 + \sum_{l = 1}^{m} b_l \cdot D\hspace{0.05cm}^l = 1 + b_1 \cdot D + b_2 \cdot D^2 + \ \text{...} \ \hspace{0.05cm} + b_m \cdot D\hspace{0.05cm}^m \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | { | + | The graphic shows the corresponding filter structure in the so–called "Controller Canonical Form":<br> |

| + | *The coefficients $a_0, \ \text{...} \ , \ a_m$ describe the forward branch. | ||

| − | + | * The coefficients $b_1, \ \text{...} \ , \ b_m$ form a feedback branch. | |

| − | + | ||

| + | *All coefficients are binary, | ||

| + | :*so $1$ $($continuous connection$)$ | ||

| + | :*or $0$ $($missing connection$)$. | ||

| + | <br clear=all> | ||

| + | {{GraueBox|TEXT= | ||

| + | $\text{Example 9:}$ The filter structure outlined on the right can be described as follows: | ||

| + | [[File:P_ID2620__KC_T_3_2_S8b_neu.png|right|frame|Filter: $G(D) = (1+D^2)/(1+D +D^2)$|class=fit]] | ||

| − | + | ::<math>x_i = w_i + w_{i-2} \hspace{0.05cm},</math> | |

| + | ::<math>w_i = u_i + w_{i-1}+ w_{i-2} \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | ||

| − | + | *Accordingly, for the D–transforms: | |

| − | : | ||

| − | :<math>W(D) = \hspace{0.08cm} U(D) + W(D) \cdot D+ W(D) \cdot D^2 | + | ::<math>X(D) =W(D) + W(D) \cdot D^2 =W(D) \cdot \left ( 1+ D^2 \right ) \hspace{0.05cm},</math> |

| + | ::<math>W(D) = \hspace{0.08cm} U(D) + W(D) \cdot D+ W(D) \cdot D^2</math> | ||

| + | ::<math>\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} | ||

U(D) = W(D) \cdot \left ( 1+ D + D^2 \right ) \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | U(D) = W(D) \cdot \left ( 1+ D + D^2 \right ) \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | ||

| − | + | *Thus, one obtains for the transfer function of this filter: | |

| − | :<math>G(D) = \frac{X(D)}{U(D)} = \frac{1+D^2}{1+D+D^2} \hspace{0.05cm}. </math> | + | ::<math>G(D) = \frac{X(D)}{U(D)} = \frac{1+D^2}{1+D+D^2} \hspace{0.05cm}. </math> |

| − | + | *In [[Channel_Coding/Algebraic_and_Polynomial_Description#Equivalent_systematic_convolutional_code| $\text{Example 8}$]] to the equivalent systematic convolutional code, exactly this expression has resulted in the lower branch.}}<br> | |

| − | == | + | == Exercises for the chapter == |

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | [[Aufgaben: | + | [[Aufgaben:Exercise_3.2:_G-matrix_of_a_Convolutional_Encoder|Exercise 3.2: G-matrix of a Convolutional Encoder]] |

| − | [[ | + | [[Aufgaben:Exercise_3.2Z:_(3,_1,_3)_Convolutional_Encoder|Exercise 3.2Z: (3, 1, 3) Convolutional Encoder]] |

| − | [[Aufgaben: | + | [[Aufgaben:Exercise_3.3:_Code_Sequence_Calculation_via_U(D)_and_G(D)|Exercise 3.3: Code Sequence Calculation via U(D) and G(D)]] |

| − | [[ | + | [[Aufgaben:Exercise_3.3Z:_Convolution_and_D-Transformation|Exercise 3.3Z: Convolution and D-Transformation]] |

| − | [[Aufgaben: | + | [[Aufgaben:Exercise_3.4:_Systematic_Convolution_Codes|Exercise 3.4: Systematic Convolution Codes]] |

| − | [[ | + | [[Aufgaben:Exercise_3.4Z:_Equivalent_Convolution_Codes%3F|Exercise 3.4Z: Equivalent Convolution Codes?]] |

| − | [[Aufgaben: | + | [[Aufgaben:Exercise_3.5:_Recursive_Filters_for_GF(2)|Exercise 3.5: Recursive Filters for GF(2)]] |

{{Display}} | {{Display}} | ||

Latest revision as of 18:50, 2 December 2022

Contents

- 1 Division of the generator matrix into partial matrices

- 2 Generator matrix of a convolutional encoder with memory $m$

- 3 Generator matrix for convolutional encoder of rate $1/n$

- 4 GF(2) description forms of a digital filter

- 5 Application of the D–transform to rate $1/n$ convolution encoders

- 6 Transfer Function Matrix

- 7 Systematic convolutional codes

- 8 Equivalent systematic convolutional code

- 9 Filter structure with fractional–rational transfer function

- 10 Exercises for the chapter

Division of the generator matrix into partial matrices

Following the discussion in the earlier section "Linear Codes and Cyclic Codes" the code word $\underline{x}$ of a linear block code can be determined from the information word $\underline{u}$ and the generator matrix $\mathbf{G}$ in a simple way: $\underline{x} = \underline{u} \cdot { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}$. The following holds:

- The vectors $\underline{u}$ and $\underline{x}$ have length $k$ $($bit count of an info word$)$ resp. $n$ $($bit count of a code word$)$ and $\mathbf{G}$ has dimension $k × n$ $(k$ rows and $n$ columns$)$.

- In convolutional coding, on the other hand $\underline{u}$ and $\underline{x}$ denote sequences with $k\hspace{0.05cm}' → ∞$ and $n\hspace{0.05cm}' → ∞$.

- Therefore, the generator matrix $\mathbf{G}$ will also be infinitely extended in both directions.

In preparation for the introduction of the generator matrix $\mathbf{G}$ in the next section,

- we define $m + 1$ "partial matrices", each with $k$ rows and $n$ columns, which we denote by $\mathbf{G}_l$

- where $0 ≤ l ≤ m$ holds.

$\text{Definition:}$ The »partial matrix« $\mathbf{G}_l$ describes the following fact:

- If the matrix element $\mathbf{G}_l(\kappa, j) = 1$, this says that the code bit $x_i^{(j)}$ is influenced by the information bit $u_{i-l}^{(\kappa)}$.

- Otherwise, this matrix element is $\mathbf{G}_l(\kappa, j) =0$.

This definition will now be illustrated by an example.

$\text{Example 1:}$ We again consider the convolutional encoder according to the diagram with the following code bits:

- \[x_i^{(1)} = u_{i}^{(1)} + u_{i-1}^{(1)}+ u_{i-1}^{(2)} \hspace{0.05cm},\]

- \[x_i^{(2)} = u_{i}^{(2)} + u_{i-1}^{(1)} \hspace{0.05cm},\]

- \[x_i^{(3)} = u_{i}^{(1)} + u_{i}^{(2)}+ u_{i-1}^{(1)} \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

Because of the memory $m = 1$ this encoder is fully characterized by the partial matrices $\mathbf{G}_0$ and $\mathbf{G}_1$ :

- \[{ \boldsymbol{\rm G} }_0 = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & 1\\ 0 & 1 & 1 \end{pmatrix} \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.5cm} { \boldsymbol{\rm G} }_1 = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 1 & 1\\ 1 & 0 & 0 \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm}.\]

These matrices are to be interpreted as follows:

- First row of $\mathbf{G}_0$, red arrows: $\hspace{1.3cm}u_i^{(1)}$ affects both $x_i^{(1)}$ and $x_i^{(3)}$, but not $x_i^{(2)}$.

- Second row of $\mathbf{G}_0$, blue arrows: $\hspace{0.6cm}u_i^{(2)}$ affects $x_i^{(2)}$ and $x_i^{(3)}$, but not $x_i^{(1)}$.

- First row of $\mathbf{G}_1$, green arrows: $\hspace{0.9cm}u_{i-1}^{(1)}$ affects all three encoder outputs.

- Second row of $\mathbf{G}_1$, brown arrow: $\hspace{0.45cm}u_{i-1}^{(2)}$ affects only $x_i^{(1)}$.

Generator matrix of a convolutional encoder with memory $m$

The $n$ code bits at time $i$ can be expressed with the partial matrices $\mathbf{G}_0, \hspace{0.05cm} \text{...} \hspace{0.05cm} , \mathbf{G}_m$ as follows:

- \[\underline{x}_i = \sum_{l = 0}^{m} \hspace{0.15cm}\underline{u}_{i-l} \cdot { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_l = \underline{u}_{i} \cdot { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_0 + \underline{u}_{i-1} \cdot { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_1 +\hspace{0.05cm} \text{...} \hspace{0.05cm} + \underline{u}_{i-m} \cdot { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_m \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

- The following vectorial quantities must be taken into account:

- \[\underline{\it u}_i = \left ( u_i^{(1)}, u_i^{(2)}, \hspace{0.05cm}\text{...} \hspace{0.1cm}, u_i^{(k)}\right )\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.5cm} \underline{\it x}_i = \left ( x_i^{(1)}, x_i^{(2)}, \hspace{0.05cm}\text{...} \hspace{0.1cm}, x_i^{(n)}\right )\hspace{0.05cm}.\]

- Considering the sequences

- \[\underline{\it u} = \big( \underline{\it u}_1\hspace{0.05cm}, \underline{\it u}_2\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.05cm}\text{...} \hspace{0.1cm}, \underline{\it u}_i\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.05cm}\text{...} \hspace{0.1cm} \big)\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.5cm} \underline{\it x} = \big( \underline{\it x}_1\hspace{0.05cm}, \underline{\it x}_2\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.05cm}\text{...} \hspace{0.1cm}, \underline{\it x}_i\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.05cm}\text{...} \hspace{0.1cm} \big)\hspace{0.05cm},\]

- starting at $i = 1$ and extending in time to infinity, this relation can be expressed by the matrix equation $\underline{x} = \underline{u} \cdot \mathbf{G}$. Here, holds for the generator matrix:

- \[{ \boldsymbol{\rm G}}=\begin{pmatrix} { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_0 & { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_1 & { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_2 & \cdots & { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_m & & & \\ & { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_0 & { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_1 & { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_2 & \cdots & { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_m & &\\ & & { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_0 & { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_1 & { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_2 & \cdots & { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_m &\\ & & & \cdots & \cdots & & & \cdots \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm}.\]

- From this equation one immediately recognizes the memory $m$ of the convolutional code.

- The parameters $k$ and $n$ are not directly readable.

- However, they are determined by the number of rows and columns of the partial matrices $\mathbf{G}_l$.

$\text{Example 2:}$ With the two matrices $\mathbf{G}_0$ and $\mathbf{G}_1$ – see $\text{Example 1}$ – the matrix sketched on the right $\mathbf{G}$ is obtained.

It should be noted:

- The generator matrix $\mathbf{G}$ actually extends downwards and to the right to infinity. Explicitly shown, however, are only eight rows and twelve columns.

- For the temporal information sequence $\underline{u} = (0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1)$ the drawn matrix part is sufficient. The encoded sequence is then:

- $$\underline{x} = (0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0).$$

- On the basis of the label colors, the $n = 3$ code word strings can be read.

- We got the same result $($in a different way$)$ in the $\text{Example 4}$ at the end of the last chapter:

- $$\underline{\it x}^{(1)} = (0\hspace{0.05cm}, 0\hspace{0.05cm}, 1\hspace{0.05cm}, 1) \hspace{0.05cm},$$

- $$\underline{\it x}^{(2)} = (1\hspace{0.05cm}, 0\hspace{0.05cm},1\hspace{0.05cm}, 1) \hspace{0.05cm},$$

- $$ \underline{\it x}^{(3)} = (1\hspace{0.05cm}, 1\hspace{0.05cm}, 1\hspace{0.05cm}, 0) \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

Generator matrix for convolutional encoder of rate $1/n$

We now consider the special case $k = 1$,

- on the one hand for reasons of simplest possible representation,

- but also because convolutional encoders of rate $1/n$ have great importance for practice.

Convolutional encoder with $k = 1, \ n = 2, \ m = 1$

- From the adjacent sketch can be derived:

- $${ \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_0=\begin{pmatrix} 1 & 1 \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.3cm} { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_1=\begin{pmatrix} 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.3cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}$$

- Thus, the resulting generator matrix is:

- $${ \boldsymbol{\rm G}}=\begin{pmatrix} 11 & 01 & 00 & 00 & 00 & \cdots & \\ 00 & 11 & 01 & 00 & 00 & \cdots & \\ 00 & 00 & 11 & 01 & 00 & \cdots & \\ 00 & 00 & 00 & 11 & 01 & \cdots & \\ \cdots & \cdots & \cdots & \cdots & \cdots & \cdots \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- For the input sequence $\underline{u} = (1, 0, 1, 1)$, the encoded sequence starts with $\underline{x} = (1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, \ \text{...})$.

- This result is equal to the sum of rows 1, 3 and 4 of the generator matrix.

Convolutional encoder with $k = 1, \ n = 2, \ m = 2$

- Due to the memory order $m = 2$ there are three submatrices here:

- \[{ \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_0=\begin{pmatrix} 1 & 1 \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.3cm} { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_1=\begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.3cm} { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_2=\begin{pmatrix} 1 & 1 \end{pmatrix}\]

- Thus, the resulting generator matrix is now:

- \[ { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}=\begin{pmatrix} 11 & 10 & 11 & 00 & 00 & 00 & \cdots & \\ 00 & 11 & 10 & 11 & 00 & 00 & \cdots & \\ 00 & 00 & 11 & 10 & 11 & 00 & \cdots & \\ 00 & 00 & 00 & 11 & 10 & 11 & \cdots & \\ \cdots & \cdots & \cdots & \cdots & \cdots & \cdots \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm}.\]

- Here the input sequence $\underline{u} = (1, 0, 1, 1)$ leads to the encoded sequence $\underline{x} = (1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, \ \text{...})$.

Convolutional encoder with $k = 1, \ n = 3, \ m = 3$

- Because of $m = 3$ there are now four partial matrices of the respective dimension $1 × 3$:

- \[{ \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_0=\begin{pmatrix} 1 & 1 & 0 \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.3cm} { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_1=\begin{pmatrix} 0 & 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.3cm} { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_2=\begin{pmatrix} 0 & 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.3cm} { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}_3=\begin{pmatrix} 0 & 1 & 1 \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm}.\]

- Thus, the resulting generator matrix is:

- \[{ \boldsymbol{\rm G}}=\begin{pmatrix} 110 & 001 & 001 & 011 & 000 & 000 & 000 & \cdots & \\ 000 & 110 & 001 & 001 & 011 & 000 & 000 & \cdots & \\ 000 & 000 & 110 & 001 & 001 & 011 & 000 & \cdots & \\ 000 & 000 & 000 & 110 & 001 & 001 & 011 & \cdots & \\ \cdots & \cdots & \cdots & \cdots & \cdots & \cdots & \cdots & \cdots \end{pmatrix}\hspace{0.05cm}.\]

- One obtains for $\underline{u} = (1, 0, 1, 1)$ the encoded sequence $\underline{x} = (1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, \ \text{...})$.

GF(2) description forms of a digital filter

In the chapter "Basics of Convolutional Coding" it was already pointed out,

- that a rate $1/n$ convolutional encoder can be realized by several digital filters,

- where the filters operate in parallel with the same input sequence $\underline{u}$ .

Before we elaborate on this statement, we shall first mention the properties of a digital filter for the Galois field ${\rm GF(2)}$.

The graph is to be interpreted as follows:

- The filter has impulse response $\underline{g} = (g_0,\ g_1,\ g_2, \ \text{...} \ ,\ g_m)$.

- For all filter coefficients $($with indices $0 ≤ l ≤ m)$ holds: $g_l ∈ {\rm GF}(2) = \{0, 1\}$.

- The individual symbols $u_i$ of the input sequence $\underline{u}$ are also binary: $u_i ∈ \{0, 1\}$.

- Thus, for the output symbol at times $i ≥ 1$ with addition and multiplication in ${\rm GF(2)}$:

- \[x_i = \sum_{l = 0}^{m} g_l \cdot u_{i-l} \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

- This corresponds to the $($discrete time$)$ »$\rm convolution$«, denoted by an asterisk. This can be used to write for the entire output sequence:

- \[\underline{x} = \underline{u} * \underline{g}\hspace{0.05cm}.\]

- Major difference compared to the chapter »"Digital Filters"« in the book "Theory of Stochastic Signals" is the modulo-2 addition $(1 + 1 = 0)$ instead of the conventional addition $(1 + 1 = 2)$.

$\text{Example 3:}$ The impulse response of the shown third order digital filter is: $\underline{g} = (1, 0, 1, 1)$.

- Let the input sequence of this filter be unlimited in time: $\underline{u} = (1, 1, 0, 0, 0, \ \text{ ...})$.

- This gives the $($infinite$)$ initial sequence $\underline{x}$ in the binary Galois field ⇒ ${\rm GF(2)}$:

- \[\underline{x} = (\hspace{0.05cm}1,\hspace{0.05cm} 1,\hspace{0.05cm} 0,\hspace{0.05cm} 0,\hspace{0.05cm} 0, \hspace{0.05cm} \text{ ...} \hspace{0.05cm}) * (\hspace{0.05cm}1,\hspace{0.05cm} 0,\hspace{0.05cm} 1,\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm})\]

- \[\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} \underline{x} =(\hspace{0.05cm}1,\hspace{0.05cm} 0,\hspace{0.05cm} 1,\hspace{0.05cm} 1,\hspace{0.05cm} 0, \hspace{0.05cm}0,\hspace{0.05cm} \text{ ...} \hspace{0.05cm}) \oplus (\hspace{0.05cm}0,\hspace{0.05cm}\hspace{0.05cm}1,\hspace{0.05cm} 0,\hspace{0.05cm} 1,\hspace{0.05cm} 1,\hspace{0.05cm}0, \hspace{0.05cm} \hspace{0.05cm} \text{ ...}\hspace{0.05cm}) = (\hspace{0.05cm}1,\hspace{0.05cm}\hspace{0.05cm}1,\hspace{0.05cm} 1,\hspace{0.05cm} 0,\hspace{0.05cm} 1,\hspace{0.05cm} 0, \hspace{0.05cm} \text{ ...} \hspace{0.05cm}) \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

- In the conventional convolution $($for real numbers$)$, on the other hand, the result would have been:

- \[\underline{x}= (\hspace{0.05cm}1,\hspace{0.05cm}\hspace{0.05cm}1,\hspace{0.05cm} 1,\hspace{0.05cm} 2,\hspace{0.05cm} 1,\hspace{0.05cm} 0, \text{ ...} \hspace{0.05cm}) \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

However, discrete time signals can also be represented by polynomials with respect to a dummy variable.

$\text{Definition:}$ The »D–transform« belonging to the discrete time signal $\underline{x} = (x_0, x_1, x_2, \ \text{...}) $ reads:

- \[X(D) = x_0 + x_1 \cdot D + x_2 \cdot D^2 + \hspace{0.05cm}\text{...}\hspace{0.05cm}= \sum_{i = 0}^{\infty} x_i \cdot D\hspace{0.05cm}^i \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

- For this particular transformation to an image area, we also use the following notation, where "D" stands for "delay operator":

- \[\underline{x} = (x_0, x_1, x_2,\hspace{0.05cm}...\hspace{0.05cm}) \quad \circ\!\!-\!\!\!-^{\hspace{-0.25cm}D}\!\!\!-\!\!\bullet\quad X(D) = \sum_{i = 0}^{\infty} x_i \cdot D\hspace{0.05cm}^i \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

Note: In the literature, sometimes $x(D)$ is used instead of $X(D)$. However, we write in our learning tutorial all image domain functions ⇒ "spectral domain functions" with capital letters, for example the Fourier transform, the Laplace transform and the D–transform:

- \[x(t) \hspace{0.15cm} \circ\!\!-\!\!\!-^{\hspace{-0.25cm}}\!\!\!-\!\!\bullet\hspace{0.15cm} X(f)\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.4cm} x(t) \hspace{0.15cm} \circ\!\!-\!\!\!-^{\hspace{-0.25cm}\rm L}\!\!\!-\!\!\bullet\hspace{0.15cm} X(p) \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.4cm} \underline{x} \hspace{0.15cm} \circ\!\!-\!\!\!-^{\hspace{-0.25cm}D}\!\!\!-\!\!\bullet\hspace{0.15cm} X(D) \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

We now apply the D–transform also

- to the information sequence $\underline{u}$, and

- the impulse response $\underline{g}$.

Due to the time limit of $\underline{g}$ the upper summation limit at $G(D)$ results in $i = m$:

- \[\underline{u} = (u_0, u_1, u_2,\hspace{0.05cm}\text{...}\hspace{0.05cm}) \quad \circ\!\!-\!\!\!-^{\hspace{-0.25cm}D}\!\!\!-\!\!\bullet\quad U(D) = \sum_{i = 0}^{\infty} u_i \cdot D\hspace{0.05cm}^i \hspace{0.05cm},\]

- \[\underline{g} = (g_0, g_1, \hspace{0.05cm}\text{...}\hspace{0.05cm}, g_m) \quad \circ\!\!-\!\!\!-^{\hspace{-0.25cm}D}\!\!\!-\!\!\bullet\quad G(D) = \sum_{i = 0}^{m} g_i \cdot D\hspace{0.05cm}^i \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

$\text{Theorem:}$ As with all spectral transformations, the »multiplication« applies to the D–transform in the image domain, since the $($discrete$)$ time functions $\underline{u}$ and $\underline{g}$ are interconnected by the »convolution«:

- \[\underline{x} = \underline{u} * \underline{g} \quad \circ\!\!-\!\!\!-^{\hspace{-0.25cm}D}\!\!\!-\!\!\bullet\quad X(D) = U(D) \cdot G(D) \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

- The $($rather simple$)$ $\rm proof$ of this important result can be found in the specification for "Exercise 3.3Z".

- As in »$\text{system theory}$« commonly, the D–transform $G(D)$ of the impulse response $\underline{g}$ is also called "transfer function".

$\text{Example 4:}$ We consider again the discrete time signals

- \[\underline{u} = (\hspace{0.05cm}1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm}\text{...}\hspace{0.05cm}) \quad \circ\!\!-\!\!\!-^{\hspace{-0.25cm}D}\!\!\!-\!\!\bullet\quad U(D) = 1+ D \hspace{0.05cm},\]

- \[\underline{g} = (\hspace{0.05cm}1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm}) \quad \circ\!\!-\!\!\!-^{\hspace{-0.25cm}D}\!\!\!-\!\!\bullet\quad G(D) = 1+ D^2 + D^3 \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

- As in $\text{Example 3}$ $($in this section above$)$, you get also on this solution path:

- \[X(D) = U(D) \cdot G(D) = (1+D) \cdot (1+ D^2 + D^3) \]

- \[\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} X(D) = 1+ D^2 + D^3 +D + D^3 + D^4 = 1+ D + D^2 + D^4 \hspace{0.3cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} \underline{x} = (\hspace{0.05cm}1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm}, \text{...} \hspace{0.05cm}) \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

- Multiplication by the "delay operator" $D$ in the image domain corresponds to a shift of one place to the right in the time domain:

- \[W(D) = D \cdot X(D) \quad \bullet\!\!-\!\!\!-^{\hspace{-0.25cm}D}\!\!\!-\!\!\circ\quad \underline{w} = (\hspace{0.05cm}0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm}1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm}, \text{...} \hspace{0.05cm}) \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

Application of the D–transform to rate $1/n$ convolution encoders

We now apply the results of the last section to a convolutional encoder, restricting ourselves for the moment to the special case $k = 1$.

- Such a $(n, \ k = 1)$ convolutional code can be realized with $n$ digital filters operating in parallel on the same information sequence $\underline{u}$.

- The graph shows the arrangement for the code parameter $n = 2$ ⇒ code rate $R = 1/2$.

The following equations apply equally to both filters, setting $j = 1$ for the upper filter and $j = 2$ for the lower filter:

- The »impulse responses« of the two filters result in

- \[\underline{g}^{(j)} = (g_0^{(j)}, g_1^{(j)}, \hspace{0.05cm}\text{...}\hspace{0.05cm}, g_m^{(j)}\hspace{0.01cm}) \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}{\rm with }\hspace{0.15cm} j \in \{1,2\}\hspace{0.05cm}.\]

- The two »output sequences« are as follows, considering that both filters operate on the same input sequence $\underline{u} = (u_0, u_1, u_2, \hspace{0.05cm} \text{...})$ :

- \[\underline{x}^{(j)} = (x_0^{(j)}, x_1^{(j)}, x_2^{(j)}, \hspace{0.05cm}\text{...}\hspace{0.05cm}) = \underline{u} \cdot \underline{g}^{(j)} \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}{\rm with }\hspace{0.15cm} j \in \{1,2\}\hspace{0.05cm}.\]

- For the »D–transform« of the output sequences:

- \[X^{(j)}(D) = U(D) \cdot G^{(j)}(D) \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}{\rm with }\hspace{0.15cm} j \in \{1,2\}\hspace{0.05cm}.\]

In order to represent this fact more compactly, we now define the following vectorial quantities of a convolutional code of rate $1/n$:

$\text{Definition:}$ The »D– transfer functions« of the $n$ parallel arranged digital filters are combined in the vector $\underline{G}(D)$:

- \[\underline{G}(D) = \left ( G^{(1)}(D), G^{(2)}(D), \hspace{0.05cm}\text{...}\hspace{0.1cm}, G^{(n)} (D) \right )\hspace{0.05cm}.\]

- The vector $\underline{X}(D)$ contains the D–transform of $n$ encoded sequences $\underline{x}^{(1)}, \underline{x}^{(2)}, \ \text{...} \ , \underline{x}^{(n)}$:

- \[\underline{X}(D) = \left ( X^{(1)}(D), X^{(2)}(D), \hspace{0.05cm}\text{...}\hspace{0.1cm}, X^{(n)} (D) \right )\hspace{0.05cm}.\]

- This gives the following vector equation:

- \[\underline{X}(D) = U(D) \cdot \underline{G}(D)\hspace{0.05cm}.\]

- $U(D)$ is not a vector quantity here because of the code parameter $k = 1$.

$\text{Example 5:}$ We consider the convolutional encoder with code parameters $n = 2, \ k = 1, \ m = 2$. For this one holds:

- \[\underline{g}^{(1)} =(\hspace{0.05cm}1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm}) \quad \circ\!\!-\!\!\!-^{\hspace{-0.25cm}D}\!\!\!-\!\!\bullet\quad G(D) = 1+ D + D^2 \hspace{0.05cm},\]

- \[\underline{g}^{(2)}= (\hspace{0.05cm}1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm}) \quad \circ\!\!-\!\!\!-^{\hspace{-0.25cm}D}\!\!\!-\!\!\bullet\quad G(D) = 1+ D^2 \]

- \[\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} \underline{G}(D) = \big ( 1+ D + D^2 \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.1cm}1+ D^2 \big )\hspace{0.05cm}.\]

- Let the information sequence be $\underline{u} = (1, 0, 1, 1)$ ⇒ D–transform $U(D) = 1 + D^2 + D^3$. This gives:

- \[\underline{X}(D) = \left ( X^{(1)}(D),\hspace{0.1cm} X^{(2)}(D) \right ) = U(D) \cdot \underline{G}(D) \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}\]

- where

- \[{X}^{(1)}(D) = (1+ D^2 + D^3) \cdot (1+ D + D^2)=1+ D + D^2 + D^2 + D^3 + D^4 + D^3 + D^4 + D^5 = 1+ D + D^5\]

- \[\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} \underline{x}^{(1)} = (\hspace{0.05cm}1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm}1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.05cm} \text{...} \hspace{0.05cm} \hspace{0.05cm}) \hspace{0.05cm},\]

- \[{X}^{(2)}(D) = (1+ D^2 + D^3) \cdot (1+ D^2)=1+ D^2 + D^2 + D^4 + D^3 + D^5 = 1+ D^3 + D^4 + D^5\]

- \[\Rightarrow \underline{x}^{(2)} = (\hspace{0.05cm}1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm}0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 1\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.05cm} 0\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.05cm} \text{...} \hspace{0.05cm} \hspace{0.05cm}) \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

- We got the same result in "Exercise 3.1Z" on other way. After multiplexing the two strands, you get again:

- $$\underline{x} = (11, 10, 00, 01, 01, 11, 00, 00, \hspace{0.05cm} \text{...} \hspace{0.05cm}).$$

Transfer Function Matrix

We have seen that a convolutional code of rate $1/n$ can be most compactly described as a vector equation in the D–transformed domain:

- $$\underline{X}(D) = U(D) \cdot \underline{G}(D).$$

Now we extend the result to convolutional encoders with more than one input ⇒ $k ≥ 2$ $($see graph$)$.

In order to map a convolutional code of rate $k/n$ in the D–domain, the dimension of the above vector equation must be increased with respect to input and transfer function:

- \[\underline{X}(D) = \underline{U}(D) \cdot { \boldsymbol{\rm G}}(D)\hspace{0.05cm}.\]

This requires the following measures:

- From the scalar function $U(D)$ we get the vector

- $$\underline{U}(D) = (U^{(1)}(D), \ U^{(2)}(D), \hspace{0.05cm} \text{...} \hspace{0.05cm} , \ U^{(k)}(D)).$$

- From the vector $\underline{G}(D)$ we get the $k × n$ transfer function matrix $($or "polynomial generator matrix"$)$ $\mathbf{G}(D)$ :