Contents

# OVERVIEW OF THE SECOND MAIN CHAPTER #

After the time variance, the term »Frequency Selectivity« is now introduced and illustrated with examples, a channel property which is also of great importance for mobile communications. As in the entire book, the description is given in the equivalent low-pass range.

It is covered in detail:

- the difference between time invariant KORREKTUR: time-invariant and time variant KORREKTUR: time-variant systems,

- the time variant KORREKTUR: time-variant impulse response as an important descriptive function of time variant KORREKTUR: time-variant systems,

- multi-way reception as the cause of frequency-selective behaviour,

- a detailed derivation and interpretation of the GWSSUS channel model,

- the characteristics of the GWSSUS model: coherence bandwidth, correlation duration, etc.

Transfer function and impulse response

The description parameters of a communication system have already been described in two chapters of the book "Linear Time Variant Systems":

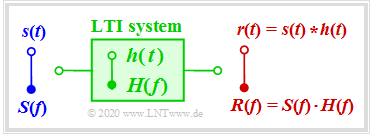

The most important results are briefly explained again here. We assume a linear and time invariant KORREKTUR: time-invariant system ⇒ $\text{LTI system}$ with the signal $s(t)$ at the input and the output signal $r(t)$. For the sake of simplicity, let $s(t)$ and $r(t)$ be real. Then the following applies:

- The system can be completely characterized by the $\text{transfer function}$ $H(f)$ which is also referred to as the "frequency response". By definition :$$H(f) = R(f)/S(f).$$

- Similarly, the system is defined by the $\text{impulse response}$ $h(t)$ , which is the $\text{inverse Fourier transform}$ of $H(f)$. The output signal results from the convolution:

- \[r(t) = s(t) \star h(t) \hspace{0.4cm} {\rm with} \hspace{0.4cm} h(t) \hspace{0.2cm} \circ\!\!-\!\!\!-\!\!\!-\!\!\bullet \hspace{0.2cm} H(f) \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

$\text{Definitions:}$ The following input signals are suitable for detecting the linear distortions caused by $H(f)$ or $h(t)$:

- a $\text{Dirac delta}$ or "impulse":

- $$s(t) = \delta(t) \hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} r(t) = \delta(t) \star h(t)= h(t)\hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} \text{impulse response,}$$

- a $\text{step function}$ or "Heaviside step function":

- $$s(t) = \gamma(t) \hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.35cm} r(t) = \gamma(t) \star h(t)\hspace{1.5cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} \text{step response,}$$

- a $\text{Dirac comb}$ or "Dirac delta train":

- $$s(t) = p_\delta(t) \hspace{0.25cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} r(t) = p_\delta(t) \star h(t)\hspace{1.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} \text{impulse response train.}$$

On the other hand, a DC signal $s(t) = A$ is not suitable to make the frequency dependence of the LTI system visible:

⇒ With a low-pass system the output signal would then be always constant, independent of $H(f)$: $r(t) = A \cdot H(f= 0)$.

In the next section we consider a Dirac delta train $p_\delta(t)$ as an input signal $s(t)$:

⇒ Hereby the similarities and differences between time-invariant and time-variant systems can be shown clearly.

Note: The properties of $H(f)$ and $h(t)$ are covered in detail in the $\text{LNTwww learning video}$ (in German language):

"Eigenschaften des Übertragungskanals" ⇒ "Some remarks on the transfer function".

Time–invariant vs. time–variant channels

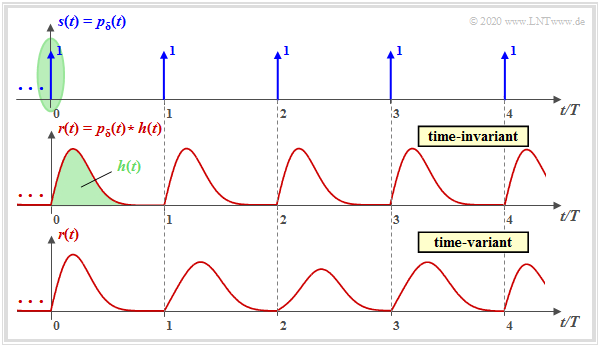

The graphic is intended to illustrate the difference between a linear time–invariant channel $\rm (LTI)$ and a linear time–variant channel $\rm (LTV)$ .

One can see from this illustration:

- The transmitted signal $s(t)$ is a Dirac delta train $p_\delta(t)$, i.e. an infinite sequence of Dirac deltas in equidistant intervals $T$, all with the weight $1$ (see upper graph):

- \[s(t) = p_{\rm \delta} (t) = \sum_{n = -\infty}^{+\infty} {\rm \delta} (t - n \cdot T) \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

- The Dirac delta at $t = 0$ is marked in green. The signal at the channel output is equal to $r(t) = h(t)$ , with $s(t) = {\rm \delta}(t)$ , also indicated in green. As a condition, it is assumed that the extension of the impulse response $h(t)$ is smaller than $T$.

.

- The entire received signal after the LTI channel, according to the middle graph, can then be written as:

- \[r(t) = p_{\rm \delta} (t) \star h(t) = \sum_{n = -\infty}^{+\infty} h (t - n \cdot T) \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

- For a time-variant channel (lower graph) this equation is not applicable. In each time interval, a (slightly) different signal shape is obtained.

$\text{Conclusion:}$ With a »time-variant channel« you cannot specify neither a one-parameter impulse response $h(t)$ nor a transfer function $H(f)$ .

Note: The differences between LTI and LTV systems are clarified with the $\text{LNTwww learning video}$ (in German language):

"Eigenschaften des Übertragungskanals" ⇒ "Some remarks on the transfer function".

Two-dimensional impulse response

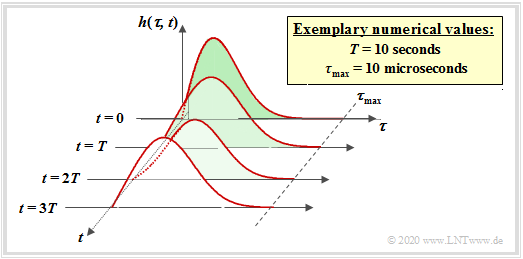

To identify a time-variant impulse response, a second parameter is used and the impulse response is preferably mapped in a three-dimensional coordinate system.

The condition for this is that the channel is still linear. One speaks then of a $\text{LTV system}$ ("linear time-variant").

The following relations apply:

- \[\text{LTI:}\hspace{0.5cm} r(t) = \int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} h(\tau) \cdot s(t-\tau) \hspace{0.15cm}{\rm d}\tau \hspace{0.05cm},\]

- \[\text{LTV:}\hspace{0.5cm} r(t) \hspace{-0.1cm} = \hspace{-0.1cm} \int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} h(\tau, \hspace{0.1cm}t) \cdot s(t-\tau) \hspace{0.15cm}{\rm d}\tau \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

Regarding the last equation and the above graph, it should be noted

- The parameter $\tau$ specifies the »delay time« to denote the time dispersion. By writing out the convolution operation, it was possible to make $\tau$ also the parameter of the LTI impulse response. In the last sections we spoke about $h(t)$ .

- The second parameter of the impulse response or the second axis marks the »absolute time« $t$, which is used, among other things, to describe the time variance. At different times $t$ the impulse response $h(\tau, \hspace{0.05cm}t)$ has a different form.

- A peculiarity of the 2D representation is that the $t$–axis is always plotted discrete-timely $($at multiples of $T)$ while the $\tau$–axis can be continuous in time as in the example shown. However, in mobile communications, a discrete-time $h(\tau, \hspace{0.05cm}t_0)$ with respect to $\tau$ is assumed $($"echoes"$)$.

- The LTV equation is only applicable if the change of the channel $($marked in the figure by the parameter $T)$ proceeds slowly in comparison to the maximum delay $\tau_{\rm max}$. In mobile communications this condition ⇒ $\tau_{\rm max} < T$ is almost always fulfilled.

- Selecting whether to apply the first Fourier integral to the parameter $\tau$ or $t$ leads to different spectral functions. In the "Exercise 2.1Z" for example, the time variant KORREKTUR: time-variant two-dimensional »2D transfer function« is considered:

- \[H(f,\hspace{0.05cm} t) \hspace{0.2cm} \bullet\!\!-\!\!\!-\!\!\!-\!\!\circ \hspace{0.2cm} h(\tau,\hspace{0.05cm}t) \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

Exercises for the chapter

Exercise 2.1: Two-Dimensional Impulse Response

Exercise 2.1Z: 2D-Frequency and 2D-Time Representations