Contents

The Huffman algorithm

We now assume that the source symbols $q_\nu$ originate from an alphabet $\{q_μ\} = \{$ $\rm A$, $\rm B$ , $\rm C$ , ...$\}$ with the symbol set size $M$ and they are statistically independent of each other. For example, for the symbol set size $M = 8$:

- $$\{ \hspace{0.05cm}q_{\mu} \} = \{ \boldsymbol{\rm A} \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} \boldsymbol{\rm B}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} \boldsymbol{\rm C}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} \boldsymbol{\rm D}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} \boldsymbol{\rm E}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} \boldsymbol{\rm F}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} \boldsymbol{\rm G}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.05cm} \boldsymbol{\rm H}\hspace{0.05cm} \}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

In 1952 - i.e. shortly after Shannon's groundbreaking publications, $\text{David A. Huffman}$ gave an algorithm for the construction of optimal prefix-free codes. This »Huffman Algorithm« is to be given here without derivation and proof, whereby we restrict ourselves to binary codes. That is: For the code symbols, let $c_ν ∈ \{$0, 1$\}$ always hold.

Here is the "recipe":

- Order the symbols according to decreasing probabilities of occurrence.

- Combine the two most improbable symbols into a new symbol.

- Repeat (1) and (2), until only two (combined) symbols remain.

- Encode the more probable set of symbols with 1 and the other set with 0.

- In the opposite direction (i.e. from bottom to top) , add 1 or 0 to the respective binary codes of the split subsets according to the probabilities.

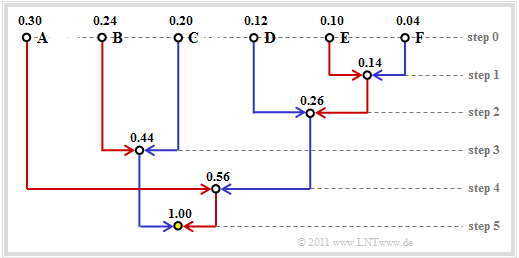

$\text{Example 1:}$ Without limiting the generality, we assume that the $M = 6$ symbols $\rm A$, ... , $\rm F$ are already ordered according to their probabilities:

- $$p_{\rm A} = 0.30 \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}p_{\rm B} = 0.24 \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}p_{\rm C} = 0.20 \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm} p_{\rm D} = 0.12 \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}p_{\rm E} = 0.10 \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}p_{\rm F} = 0.04 \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

By pairwise combination and subsequent sorting, the following symbol combinations are obtained in five steps (resulting probabilities in brackets):

- 1. $\rm A$ (0.30), $\rm B$ (0.24), $\rm C$ (0.20), $\rm EF$ (0.14), $\rm D$ (0.12),

- 2. $\rm A$ (0.30), $\rm EFD$ (0.26), $\rm B$ (0.24), $\rm C$ (0.20),

- 3. $\rm BC$ (0.44), $\rm A$ (0.30), $\rm EFD$ (0.26),

- 4. $\rm AEFD$ (0.56), $\rm BC$ (0.44),

- 5. Root $\rm AEFDBC$ (1.00).

Backwards – i.e. according to steps (5) to (1) – the assignment to binary symbols then takes place. An "x" indicates that bits still have to be added in the next steps:

- 5. $\rm AEFD$ → 1x, $\rm BC$ → 0x,

- 4. $\underline{\rm A}$ → 11, $\rm EFD$ → 10x,

- 3. $\underline{\rm B}$ → 01, $\underline{\rm C}$ → 00,

- 2. $\rm EF$ → 101x, $\underline{\rm D}$ → 100,

- 1. $\underline{\rm E}$ → 1011, $\underline{\rm F}$ → 1010.

The underlines mark the final binary coding.

On the term "Entropy Coding"

We continue to assume the probabilities and assignments of the last example:

- $$p_{\rm A} = 0.30 \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}p_{\rm B} = 0.24 \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}p_{\rm C} = 0.20 \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm} p_{\rm D} = 0.12 \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}p_{\rm E} = 0.10 \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}p_{\rm F} = 0.04 \hspace{0.05cm};$$

- $$\boldsymbol{\rm A} \hspace{0.05cm} \rightarrow \hspace{0.05cm} \boldsymbol{\rm 11} \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm} \boldsymbol{\rm B} \hspace{0.05cm} \rightarrow \hspace{0.05cm} \boldsymbol{\rm 01} \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm} \boldsymbol{\rm C} \hspace{0.05cm} \rightarrow \hspace{0.05cm} \boldsymbol{\rm 00} \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm} \boldsymbol{\rm D} \hspace{0.05cm} \rightarrow \hspace{0.05cm} \boldsymbol{\rm 100} \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm} \boldsymbol{\rm E} \hspace{0.05cm} \rightarrow \hspace{0.05cm} \boldsymbol{\rm 1011} \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm} \boldsymbol{\rm F} \hspace{0.05cm} \rightarrow \hspace{0.05cm} \boldsymbol{\rm 1010} \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

Thus, of the six source symbols, three are encoded with two bits each, one with three bits and two symbols $(\rm E$ and $\rm F)$ with four bits each.

The average code word length thus results in

- $$L_{\rm M} = (0.30 \hspace{-0.05cm}+ \hspace{-0.05cm}0.24 \hspace{-0.05cm}+ \hspace{-0.05cm} 0.20) \cdot 2 + 0.12 \cdot 3 + (0.10 \hspace{-0.05cm}+ \hspace{-0.05cm} 0.04 ) \cdot 4 = 2.4 \,{\rm bit/source\hspace{0.15cm}symbol} \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

From the comparison with the source entropy $H = 2.365 \ \rm bit/source\hspace{0.15cm}symbol$ one can see the efficiency of the Huffman coding.

$\text{Note:}$ There is no prefix-free $($⇒ immediately decodable$)$ code that leads to a smaller average code word length $L_{\rm M}$ than the Huffman code by exploiting the occurrence probabilities alone. In this sense, the Huffman code is optimal.

$\text{Example 2:}$ If the symbol probabilities were

- $$p_{\rm A} = p_{\rm B} = p_{\rm C} = 1/4 \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm} p_{\rm D} = 1/8 \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}p_{\rm E} = p_{\rm F} = 1/16 \hspace{0.05cm},$$

then the same would apply to the entropy and to the average code word length:

- $$H = 3 \cdot 1/4 \cdot {\rm log_2}\hspace{0.1cm}(4) + 1/8 \cdot {\rm log_2}\hspace{0.1cm}(8) + 2 \cdot 1/16 \cdot {\rm log_2}\hspace{0.1cm}(16) = 2.375 \,{\rm bit/source\hspace{0.15cm} symbol}\hspace{0.05cm},$$

- $$L_{\rm M} = 3 \cdot 1/4 \cdot 2 + 1/8 \cdot 3 + 2 \cdot 1/16 \cdot 4 = 2.375 \,{\rm bit/source\hspace{0.15cm} symbol} \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

This property $L_{\rm M} = H +\varepsilon$ with positive $\varepsilon \to 0$ at suitable symbol probabilities explains the term »Entropy Coding«:

In this form of source coding, one tries to adapt the length $L_μ$ of the binary sequence (consisting of zeros and ones) for the symbol $q_μ$ according to the entropy calculation to its symbol probability $p_μ$ as follows:

- $$L_{\mu} = {\rm log}_2\hspace{0.1cm}(1/p_{\mu} ) \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

Of course, this does not always succeed, but only if all symbol probabilities $p_μ$ can be represented in the form $2^{–k}$ with $k = 1, \ 2, \ 3,$ ...

- In this special case - and only in this case - the average code word length $L_{\rm M}$ coincides exactly with the source entropy $H$ $(\varepsilon = 0$, see $\text{Example 2})$.

- According to the $\text{Source Coding Theorem}$ there is no (decodable) code that gets by with fewer binary characters per source symbol on average.

Representation of the Huffman code as a tree diagram

A »tree structure« is often used to construct the Huffman code. For the example considered so far, this is shown in the following diagram:

It can be seen:

- At each step of the Huffman algorithm, the two branches with the smallest respective probabilities are combined.

- The node in the first step combines the two symbols $\rm E$ and $\rm F$ with the currently smallest probabilities. This new node is labelled $p_{\rm E} + p_{\rm F} = 0.14$ .

- The branch running from the symbol with the smaller probability $($here $\rm F)$ to the sum node is drawn in blue, the other branch $($here $\rm E)$ in red.

- After five steps, we arrive at the root of the tree with the total probability $1.00$ .

If you now trace the course from the root (in the graphic with yellow filling) back to the individual symbols, you can read off the symbol assignment from the colours of the individual branches.

For example, with the assignments "red" → 1 and "blue" → 0, the following results from the root to the symbol

- $\rm A$: red, red → 11,

- $\rm B$: blue, red → 01,

- $\rm C$: blue, blue → 00,

- $\rm D$: red, blue, blue → 100,

- $\rm E$: red, blue, red, red → 1011,

- $\rm F$: red, blue, red, blue → 1010.

The (uniform) assignment "red" → 0 and "blue" → 1 would also lead to an optimal prefix-free Huffman code.

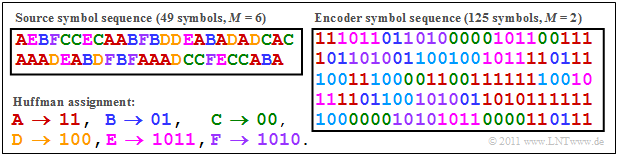

$\text{Example 3:}$ The following graph shows the Huffman coding of $49$ symbols $q_ν ∈ \{$ $\rm A$, $\rm B$, $\rm C$, $\rm D$, $\rm E$, $\rm F$ $\}$ with the assignment derived in the last section. The different colours serve only for better orientation.

- The binary encoded sequence has the average code word length

- $$L_{\rm M} = 125/49 = 2.551.$$

- Due to the short sequence $(N = 49)$ , the frequencies $h_{\rm A}$, ... , $h_{\rm F}$ of the simulated sequences deviate significantly from the given probabilities $p_{\rm A}$, ... , $p_{\rm F}$ :

- $$p_{\rm A} = 0.30 \hspace{0.05cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.05cm} h_{\rm A} = 16/49 \approx 0.326 \hspace{0.05cm},$$

- $$p_{\rm B} = 0.24 \hspace{0.05cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.05cm} h_{\rm B} = 7/49 \approx 0.143 \hspace{0.05cm},$$

- $$p_{\rm C} =0.24 \hspace{0.05cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.05cm} h_{\rm C}= 9/49 \approx 0.184 \hspace{0.05cm},$$

- $$p_{\rm D} = 0.12 \hspace{0.05cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.05cm} h_{\rm D} = 7/49 \approx 0.143 \hspace{0.05cm},$$

- $$p_{\rm E}=0.10 \hspace{0.05cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.05cm} h_{\rm E} = 5/49 \approx 0.102 \hspace{0.05cm},$$

- $$p_{\rm F} = 0.04 \hspace{0.05cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.05cm} h_{\rm E} = 5/49 \approx 0.102 \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- This results in a slightly larger entropy value:

- $$H ({\rm regarding}\hspace{0.15cm}p_{\mu}) = 2.365 \ {\rm bit/source\hspace{0.15cm} symbol}\hspace{0.3cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} H ({\rm regarding}\hspace{0.15cm}h_{\mu}) = 2.451 \ {\rm bit/source\hspace{0.15cm} symbol} \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

If one were to form the Huffman code with these "new probabilities" $h_{\rm A}$, ... , $h_{\rm F}$ the following assignments would result:

- $\boldsymbol{\rm A} \hspace{0.05cm} \rightarrow \hspace{0.15cm}$11$\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm} \boldsymbol{\rm B} \hspace{0.05cm} \rightarrow \hspace{0.15cm}$100$\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm} \boldsymbol{\rm C} \hspace{0.05cm} \rightarrow \hspace{0.15cm}$00$\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm} \boldsymbol{\rm D} \hspace{0.05cm} \rightarrow \hspace{0.15cm}$101$\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm} \boldsymbol{\rm E} \hspace{0.05cm} \rightarrow \hspace{0.15cm}$010$\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm} \boldsymbol{\rm F} \hspace{0.05cm} \rightarrow \hspace{0.15cm}$011$\hspace{0.05cm}.$

Now only $\rm A$ and $\rm C$ would be represented by two bits, the other four symbols by three bits each.

- The encoded sequence would then have a length of $(16 + 9) · 2 + (7 + 7 + 5 + 5) · 3 = 122$ bits, ⇒ three bits shorter than under the previous coding.

- The average code word length would then be $L_{\rm M} = 122/49 ≈ 2.49$ bit/source symbol instead of $L_{\rm M}≈ 2.55$ bit/source symbol.

The (German language) interactive applet "Huffman- und Shannon-Fano-Codierung ⇒ $\text{SWF}$ version" illustrates the procedure for two variants of entropy coding.

$\text{This example can be interpreted as follows:}$

- Huffman coding thrives on the (exact) knowledge of the symbol probabilities. If these are known to both the transmitter and the receiver, the average code word length $L_{\rm M}$ is often only insignificantly larger than the source entropy $H$.

- Especially with small files, there may be deviations between the (expected) symbol probabilities $p_μ$ and the (actual) frequencies $h_μ$ . It would be better here to generate a separate Huffman code for each file based on the actual circumstances $(h_μ)$.

- In this case, however, the specific Huffman code must also be communicated to the decoder. This leads to a certain overhead, which again can only be neglected for longer files. With small files, this effort is not worthwhile.

Influence of transmission errors on decoding

Due to the property "prefix-free" ⇒ the Huffman code is lossless.

- This means that the source symbol sequence can be completely reconstructed from the binary encoded sequence.

- However, if an error occurs during transmission $($"0" ⇒ "1" or "1" ⇒ "0"$)$, , the sink symbol sequence $〈v_ν〉$ naturally also does not match the source symbol sequence $〈q_ν〉$.

The following two examples show that a single transmission error can sometimes result in a multitude of errors regarding the source text.

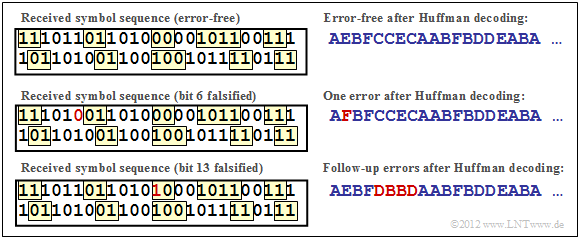

$\text{Example 4:}$ We consider the same source symbol sequence and the same Huffman code as in the previous section.

- The upper diagram shows that with error-free transmission, the original source sequence 111011... can be reconstructed from the coded binary sequence $\rm AEBFCC$...

- However, if for example bit 6 is falsified $($from 1 to 0, red marking in the middle graphic$)$, the source symbol $q_2 = \rm E$ becomes the sink symbol $v_2 =\rm F$.

- A falsification of bit 13 $($from 0 to 1, red marking in the lower graphic$)$ even leads to a falsification of four source symbols: $\rm CCEC$ → $\rm DBBD$.

$\text{Example 5:}$ Let a second source with symbol set size $M = 6$ be characterized by the following symbol probabilities:

- $$p_{\rm A} = 0.50 \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}p_{\rm B} = 0.19 \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}p_{\rm C} = 0.11 \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm} p_{\rm D} = 0.09 \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}p_{\rm E} = 0.06 \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}p_{\rm F} = 0.05 \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

Here the Huffman algorithm leads to the following assignment:

- $\boldsymbol{\rm A} \hspace{0.05cm} \rightarrow \hspace{0.15cm}$0$\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm} \boldsymbol{\rm B} \hspace{0.05cm} \rightarrow \hspace{0.15cm}$111$\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm} \boldsymbol{\rm C} \hspace{0.05cm} \rightarrow \hspace{0.15cm}$101$\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm} \boldsymbol{\rm D} \hspace{0.05cm} \rightarrow \hspace{0.15cm}$100$\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm} \boldsymbol{\rm E} \hspace{0.05cm} \rightarrow \hspace{0.15cm}$1101$\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm} \boldsymbol{\rm F} \hspace{0.05cm} \rightarrow \hspace{0.15cm}$1100$\hspace{0.05cm}.$

The source symbol sequence $\rm ADABD$... (upper diagram) is thus represented by the encoded sequence 0'100'0'111'100' ... . The inverted commas are only for the reader's orientation.

During transmission, the first bit is distorted KORREKTUR: falsified: Instead of 01000111100... one receives 11000111100...

- After decoding, the first two source symbols $\rm AD$ → 0100 become the sink symbol $\rm F$ → 1100.

- The further symbols are then detected correctly again, but now no longer starting at position $ν = 3$, but at $ν = 2$.

Depending on the application, the effects are different:

- If the source is a "natural text" and the sinker is a "human", most of the text remains comprehensible to the reader.

- If, however, the sink is an automaton that successively compares all $v_ν$ with the corresponding $q_ν$, the result is a distortion frequency of well over $50\%$.

- Only the blue symbols of the sink symbol sequence $〈v_ν〉$ then (coincidentally) match the source symbols $q_ν$ while red symbols indicate errors.

Application of Huffman coding to $k$–tuples

The Huffman algorithm in its basic form delivers unsatisfactory results when

- there is a binary source $(M = 2)$ , for example with the symbol set $\{$ $\rm X$, $\rm Y \}$,

- there are statistical dependencies between adjacent symbols of the input sequence,

- the probability of the most frequent symbol is clearly greater than $50\%$.

The remedy in these cases is

- by grouping several symbols together, and

- applying the Huffman algorithm to a new set of symbols $\{$ $\rm A$, $\rm B$, $\rm C$, $\rm D$, ... $\}$ .

If $k$–tuples are formed, the symbol set size $M$ increases to $M\hspace{-0.01cm}′ = M^k$.

In the following example, we will illustrate the procedure using a binary source. Further examples can be found in

$\text{Example 6:}$ Let a memoryless binary source $(M = 2)$ with the symbols $\{$ $\rm X$, $\rm Y \}$ be given:

- Let the symbol probabilities be $p_{\rm X} = 0.8$ and $p_{\rm Y} = 0.2$. Thus the source entropy is $H = 0.722$ bit/source\hspace{0.15cm}symbol.

- We consider the symbol sequence $\{\rm XXXYXXXXXXXXYYXXXXXYYXXYXYXXYX\ \text{...} \}$ with only a few $\rm Y$ symbols at positions 4, 13, 14, ...

The Huffman algorithm cannot be applied directly to this source, that is, one also needs a bit for each binary source symbol without further action. But:

If one combines two binary symbols at a time into a tuple of two $(k = 2)$ corresponding to $\rm XX$ → $\rm A$, $\rm XY$ → $\rm B$, $\rm YX$ → $\rm C$, $\rm YY$ → $\rm D$ , one can apply "Huffman" to the resulting sequence → $\rm ABAACADAABCBBAC$ ... → with $M\hspace{-0.01cm}′ = 4$. Because of

- $$p_{\rm A}= 0.8^2 = 0.64 \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}p_{\rm B}= 0.8 \cdot 0.2 = 0.16 = p_{\rm C} \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} p_{\rm D}= 0.2^2 = 0.04,$$

we get $\rm A$ → 1, $\rm B$ → 00, $\rm C$ → 011, $\rm D$ → 010 as well as

- $$L_{\rm M}\hspace{0.03cm}' = 0.64 \cdot 1 + 0.16 \cdot 2 + 0.16 \cdot 3 + 0.04 \cdot 3 =1.56\,\text{bit/two-tuple}$$

- $$\Rightarrow\hspace{0.3cm}L_{\rm M} = {L_{\rm M}\hspace{0.03cm}'}/{2} = 0.78\ {\rm bit/source\hspace{0.15cm}symbol}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

Now we form tuples of three $(k = 3)$, corresponding to

- $\rm XXX$ → $\rm A$, $\rm XXY$ → $\rm B$, $\rm XYX$ → $\rm C$, $\rm XYY$ → $\rm D$, $\rm YXX$ → $\rm E$, $\rm YXY$ → $\rm F$, $\rm YYX$ → $\rm G$, $\rm YYY$ → $\rm H$.

- For the input sequence given above, one arrives at the equivalent output sequence $\rm AEBAGADBCC$ ... (based on the new symbol set size $M\hspace{-0.01cm}′ = 8$) and to the following probabilities:

- $$p_{\rm A}= 0.8^3 = 0.512 \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.5cm}p_{\rm B}= p_{\rm C}= p_{\rm E} = 0.8^2 \cdot 0.2 = 0.128\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.5cm} p_{\rm D}= p_{\rm F}= p_{\rm G} = 0.8 \cdot 0.2^2 = 0.032 \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.5cm}p_{\rm H}= 0.2^3 = 0.008\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- The Huffman coding is thus:

- $\rm A$ → 1, $\rm B$ → 011, $\rm C$ → 010, $\rm D$ → 00011, $\rm E$ → 001, $\rm F$ → 00010, $\rm G$ → 00001, $\rm H$ → 00000.

- Thus, for the average code word length we obtain:

- $$L_{\rm M}\hspace{0.03cm}' = 0.512 \cdot 1 + 3 \cdot 0.128 \cdot 3 + (3 \cdot 0.032 + 0.008) \cdot 5 =2.184 \,{\text{bit/three-tuple} } $$

- $$\Rightarrow\hspace{0.3cm}L_{\rm M} = {L_{\rm M}\hspace{0.03cm}'}/{3} = 0.728\ {\rm bit/source\hspace{0.15cm} symbol}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- In this example, therefore, the source entropy $H = 0.722$ bit/source symbol is almost reached already with $k = 3$.

Exercises for the chapter

Exercise 2.6: About the Huffman Coding

Exercise 2.6Z: Again on the Huffman Code

Exercise 2.7: Huffman Application for Binary Two-Tuples

Exercise 2.7Z: Huffman Coding for Two-Tuples of a Ternary Source

Exercise 2.8: Huffman Application for a Markov Source

Exercise 2.9: Huffman Decoding after Errors