Contents

- 1 # OVERVIEW OF THE FIRST MAIN CHAPTER #

- 2 Goals and features of ISDN

- 3 Services and service features of ISDN

- 4 Network infrastructure for ISDN

- 5 Attenuation behavior of copper cables

- 6 Four-wire and two-wire transmission

- 7 Einige Grundlagen von PCM

- 8 Entstehung und historische Entwicklung

- 9 Aufgaben zum Kapitel

- 10 Quellenverzeichnis

# OVERVIEW OF THE FIRST MAIN CHAPTER #

$\rm I$ntegrated $\rm S$ervices $\rm D$igital $\rm N$etwork – ISDN for short – was the first unified digital network for voice, text, data, images, video and multimedia communications.

ISDN was introduced in the late 1980s and had about 25 million users in Germany in 2004. Compared with the analog telecommunications processes that were common before, ISDN has

- offered many new or enhanced services,

- faster transmission,

- better voice quality, and

- an easier use of multiple devices.

The ISDN concept and implementation are presented and explained in this chapter, and in particular are covered:

- a general description of ISDN,

- the services and service features of ISDN,

- the ISDN network infrastructure and the different types of connection,

- the logical channels and interfaces of ISDN,

- the most important transmission codes of ISDN, and

- broadband ISDN as a further development.

At the time of the last revision of this book (2017), however, it should not be kept secret that ISDN will no longer have much of a future in Germany either – in other countries it never had the significance it has here.

- Deutsche Telekom has announced that ISDN will be switched off in 2018 and replaced by the Next Generation Network (NGN) with packet-switched network infrastructure.

- Vodafone will follow this example by 2022 at the latest.

Goals and features of ISDN

The $\rm ISDN$ (Integrated Services Digital Network) standard, established since the late 1980s, is a service-integrated digital communications network with the aim,

- to digitize the analog signal transmission over telephone lines that had been common until then, thereby achieving better voice quality,

- to continue using the network infrastructure available for analog signal transmission – in particular the copper cables laid at great expense over many years,

- integrate different sources of information such as voice, text, data and video, as well as the emerging multimedia communications, into a single network,

- to enable different telecommunication services such as telephoning, faxing, Internet surfing and much more to be provided simultaneously over the existing network of lines,

- to keep the number of lines required as low as possible without compromising the quality of the transmission, and finally

- to provide a data rate of $\text{64 kbit/s}$, which was also considered sufficient for data traffic when ISDN was introduced.

A distinction is made with ISDN between

- the "ISDN basic access" with two so-called B channels (Bearer Channels) with $\text{64 kbit/s}$ each and a D channel (Data Channel) with $\text{16 kbit/s}$, and

- the "ISDN primary multiplex connection" with thirty B channels and one signaling and one synchronization channel, each at $\text{64 kbit/s}$.

By bundling two channels, the data rate could be increased to $\text{128 kbit/s}$.

- Since the introduction of ISDN in March 1989, the quality of voice transmission and the bit error rate during data transmission have also been steadily improved.

- The ATM-based "broadband ISDN" (B–ISDN) standardized in 1994 also allows significantly higher data rates.

Services and service features of ISDN

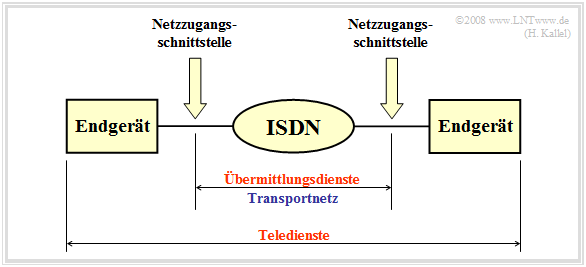

The available ISDN services can be divided into two groups:

Bearer services are used to transport information and ensure data transmission and switching between the access interfaces of the network. This corresponds to definitions in the first three layers of the "OSI reference model":

- $\rm PL$ (Physical Layer),

- $\rm DL$ (Data Link Layer), and

- $\rm NL$ (Network Layer).

Bearer services include

- circuit-switched services, for example

- data transmission with 64 kbit/s (on the S0 bus or via the X21 terminal adapter) and audio transmission (voice and music up to 3400 Hz) as in the analog telephone network,

- packet-switched services – for example, access to the packet network in the B channel.

Tele services also include terminal equipment. They are therefore end-to-end services. They include

- switching functions and protocols in layers 1 to 3, and

- functions for controlling communication processes in layers 4 to 7 of the OSI reference model.

The most important tele services are:

- ISDN telephony with a bandwidth of 3.1 kHz or 7 kHz (with B–ISDN) – also with transitions to the analog fixed network and to radio networks,

- ISDN teletext with 64 kbit/s and transitions to telebox services (mailbox), T-Online services and Datex L/P services,

- ISDN telefax, e.g. group 4 telecopier with transitions to group 3,

- ISDN–mixed mode, which is understood to mean mixed, simultaneous data transmission of texts and images,

- ISDN T–Online with 64 kbit/s and transitions to T-Online in the analog telephone network as well as to group 3 and 4 telefax,

- Video telephony – in practice, however, only possible as slow moving image transmission,

- data communications using standardized protocols, such as file transfer with FTAM (comparable, but technically not identical, to the Internet service FTP).

$\text{Conclusion:}$ Service features as subsets of a service can be divided into three categories:

- Access service features: Dial-up or fixed connection, line or packet switching, and terminal selection on the S0 bus,

- Connection service features: fast connection setup or conference connection,

- Information service feature: event information, identification of other subscribers, display of charges and tariffs.

Network infrastructure for ISDN

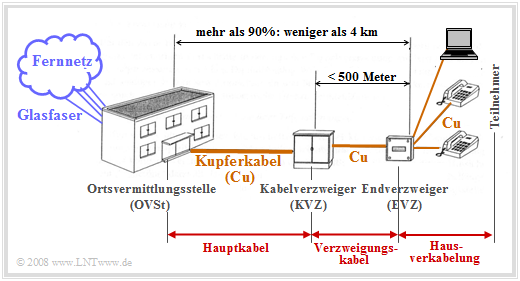

ISDN, which was developed in the early 1980s, was intended to use the existing analog telephone network for cost reasons. The greatest cost factor of the entire infrastructure is the subscriber line area between the local exchange (OVSt) or a main distribution frame (HVt) and the subscribers, as the network branches out to the maximum in this area. In Germany, this so-called "last mile" is shorter than 4 kilometers on average, and in urban areas 90% of the time it is even shorter than 2.8 kilometers.

Due to the topological conditions, the telephone network is increasingly branching out in a star configuration toward the end customer. In order to avoid having to lay a separate copper cable to the local exchange for each subscriber, splitters have been installed in between and the lines bundled in correspondingly large cables.

The local loop area is therefore usually made up as follows:

- the main cable with up to 2000 pairs between the local exchange (OVSt) or the main distribution frame and a cable branch,

- the branch cable between the cable branch and the final branch, with up to 300 pairs and a maximum length of 500 meters, which is significantly shorter than a main cable,

- the house connection cable between the terminal box and the network termination box at the subscriber with two pairs of wires.

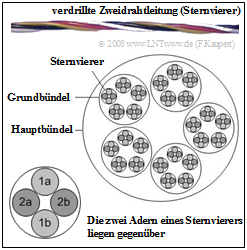

In order to reduce the inductive and capacitive influences of neighboring pairs of conductors and thus increase the packing density, two pairs of twisted pairs are twisted into a so-called star quad.

The figure shows such a star quad and a bundle cable. In the example shown

- five such quads each are combined to form a basic bundle, and

- five basic bundles are combined into one main bundle. The cable contains 50 pairs with PE insulation.

Attenuation behavior of copper cables

In the past, copper two-wire lines - usually designated "Cu" in network diagrams - with core diameters of 0.35 mm, 0.4 mm and 0.5 mm were laid in the area of the Deutsche Bundespost (today: Deutsche Telekom).

- In the chapter "Properties of Electrical Cables" of the book "Linear and Time Invariant Systems", the electrical properties of copper lines are described in detail.

- Here we limit ourselves to a few properties that are of interest with regard to their use with ISDN.

All following statements refer to lines with 0.4 mm diameter.

For these, for example, in [PW95][1] the following empirically found attenuation and phase curve were given, where $l$ denotes the line length:

- $${a_{\rm K}(f)}/{ {\rm dB}} = \left [ 5.1 + 14.3 \cdot \left ({f}/{ {\rm MHz}}\right )^{0.59}\right ]\cdot{l}/{ {\rm km}} \hspace{0.05cm},$$

- $${b_{\rm K}(f)}/{ {\rm rad}} = \left [ 32.9 \cdot \frac{f}{ {\rm MHz}} + 2.26 \cdot \left ({f}/{ {\rm MHz}}\right )^{0.5}\right ]\cdot{l}/{ {\rm km}} \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

With the interactive applet "Attenuation of copper cables" you can view the attenuation curve of symmetrical lines and coaxial cables with different dimensions and with another applet the "Time behavior of copper cables".

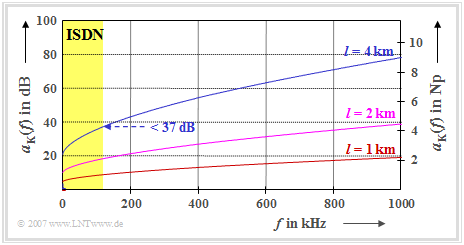

The diagram shows the attenuation curve in the frequency range up to $1 \ \rm MHz$ for the cable lengths $l = 1 \ \rm km$, $l = 2 \ \rm km$ and $l = 4 \ \rm km$ with a cable diameter of $\text{0.4 mm}$. One can see from this diagram:

- The attenuation function $a_{\rm K}(f)$ for one kilometer of cable length is between $5.1 \ \rm dB$ $($bei $f = 0)$ and $19.4 \ \rm dB$ $($at $f = 1 \ \rm MHz)$ and is proportional to the cable length. For $l = 4 \ \rm km$, these values quadruple.

- Cables with a length of $4 \ \rm km$ occur in ISDN at most on the $\rm U_{\rm K0}$ bus, i.e. on the connection between the local exchange and the terminal. Due to the 4B3T coding, the symbol sequence frequency here is only $120 \ \rm kHz$.

- In the diagram, this ISDN–relevant range is highlighted in yellow. At $f = 120 \ \rm kHz$ and $l = 4 \ \rm km$, the attenuation is approx. $37 \ \rm dB$, which is rather moderate compared to broadband "DSL" (Digital Subscriber Line). This means: cable attenuation is not critical for ISDN.

- The above attenuation curve only applies to the "two-wire line" transmission medium. In the ISDN access network, however, there are also transformers with the consequence that DC signal components cannot be transmitted over them.

- For the ISDN system, this fact means that in the access network (on the $\rm U_{\rm K0}$ bus), line coding – more precisely, the "4B3T code" – must be used to ensure that the transmitted signal is free of common signals.

- Furthermore, it must be taken into account that in two-wire lines in cable bundles, the "crosstalk from neighboring wires" is the dominant source of noise and not, for example, the thermal noise as in a coaxial cable system.

- Therefore, the bit error probability cannot be reduced here by increasing the transmitting power, since a higher level would amplify the noise signal (for other pairs) in the same way as the useful signal.

- Of the crosstalk noise, near-end crosstalk is more critical than far-end crosstalk. Near-end crosstalk occurs when two adjacent pairs of wires are operated in different directions, so that the disturbed receiver is located close to the interfering transmitter. In long-distance crosstalk, on the other hand, the induced noise power is noticeably attenuated by the cable attenuation and thus has less effect.

Four-wire and two-wire transmission

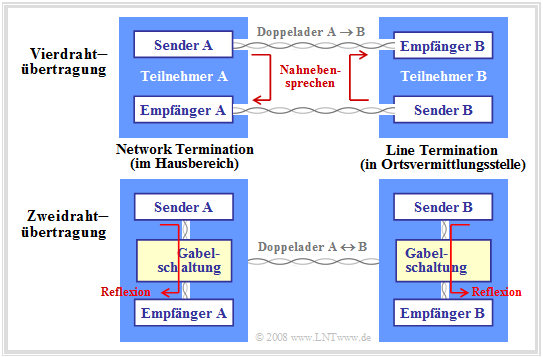

Eine Kommunikationsverbindung arbeitet meist – so auch bei ISDN – im Vollduplexbetrieb, das heißt, die beiden Kommunikationspartner senden kontinuierlich und unabhängig voneinander.

- Um diese Betriebsart zu gewährleisten, sind verschiedene Varianten möglich, die in der Grafik dargestellt sind.

- Die Sende– und Empfangseinrichtung beim Kunden $($Teilnehmer $\rm A)$ wird als Network Termination (NT) bezeichnet,

- die entsprechende Gegenstelle in der Ortsvermittlungsstelle heißt Line Termination (LT).

Es gibt zwei Möglichkeiten für einen solchen Vollduplexbetrieb:

- Man kann die Kommunikation von $\rm A$ → $\rm B$ und die Gegenrichtung von $\rm B$ → $\rm A$ über getrennte Leitungen realisieren. Eine solche Vierdrahtübertragung wird bei ISDN im Hausanschlussbereich – dem sogenannen $\rm S_{\rm 0}$–Bus – angewendet, wobei für jede Richtung eine Doppelader zur Verfügung gestellt wird.

- Ökonomischer ist die gemeinsame Nutzung einer Doppelader für beide Richtungen – also die so genannte Zweidrahtübertragung. Diese wird bei ISDN im Zugangsnetz – auf dem $\rm U_{\rm K0}$–Bus – angewendet. Da für beide Richtungen der gleiche Frequenzbereich benutzt wird, spricht man auch vom Zweidraht–Frequenzgleichlageverfahren.

$\text{Fazit:}$

- Bei der Vierdrahtübertragung kann es über die ersten Meter der Leitung durch induktive oder kapazitive Kopplungen zu Nahnebensprechen (siehe vorherige Seite) kommen, das heißt, der Sender stört den eigenen Empfänger.

- Bei der Zweidrahtvariante ist die interne Reflexion des Sendesignals in den (eigenen) Empfänger die dominante Störungsursache, die bei schmalbandigen Sendesignalen (beispielsweise Sprache) durch eine Gabelschaltung vermieden oder vermindert werden kann. Bei Breitbandsignalen sind zusätzlich aufwändige adaptive Verfahren zur Echokompensation erforderlich.

Einige Grundlagen von PCM

Das ISDN–Konzept basiert weitgehend auf der Pulscodemodulation (PCM), deren Grundzüge schon 1938 von Alec Reeves entwickelt wurden. Dieses wichtige Grundlagengebiet für die digitalen Modulation und die Digitalsignalübertragung wird im Buch Modulationsverfahren detailliert beschrieben. Hier folgt eine kurze Zusammenfassung in Hinblick auf die Verwendung bei ISDN.

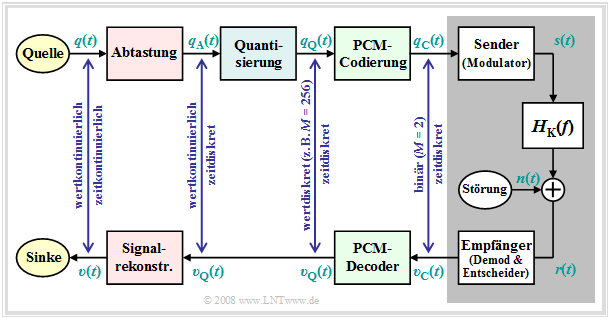

Die Grafik zeigt das Blockschaltbild des PCM–Übertragungssystems, das an die Gegebenheit bei ISDN angepasst ist. Man erkennt:

- Das analoge (das heißt: wert– und zeitkontinuierliche) Quellensignal $q(t)$ wird durch die drei Funktionsblöcke Abtastung – Quantisierung – PCM–Codierung in das Binärsignal $q_{\rm C}(t)$ gewandelt. In der Grafik ist dies im oberen Signalpfad dargestellt.

- Der grau hinterlegte Block zeigt das "Digitale Übertragungssystem" mit Sender, Kanalverzerrungen und Rauschaddition sowie dem Digitalempfänger, der unter anderem einen Entscheider beinhaltet. Das Kanalausgangssignal $v_{\rm C}(t)$ ist wie $q_{\rm C}(t)$ ein Binärsignal.

- Im unteren Zweig erkennt man den PCM–Decoder mit dem zeitdiskreten, nun aber höherstufigen Ausgangssignal $v_{\rm Q}(t)$. Anschließend folgt die Signalrekonstruktion zur Gewinnung des Analogsignals $v(t)$, wozu ein idealer, rechteckförmiger Tiefpass ausreicht.

- Für die Quantisierung gibt es empfängerseitig keine Entsprechung. Das heißt: Die beim Sender unvermeidbaren Quantisierungsfehler sind irreversibel. Deshalb gilt bei PCM wie bei jeder Form von Digitalsignalübertragung grundsätzlich $v(t) ≠ q(t)$.

- Ein wichtiger Quantisierungsparameter ist die Stufenzahl $M = 2^N$, wobei $N$ die Anzahl der für einen Abtastwert erforderlichen Binärzeichen angibt. Je größer $N$ ist, desto weniger stark ist der störende Einfluss der Quantisierung und um so höher die Qualität des PCM–Systems.

Alle diese Aussagen gelten für PCM allgemein. Nun werden die Besonderheiten der Pulscodemodulation bei ISDN genannt.

$\text{Pulscodemodulation bei ISDN:}$ Die Abtastung im Zeitabstand $T_{\rm A}$ erfolgt entsprechend dem Abtasttheorem. Dieses besagt:

- Besitzt das Spektrum $Q(f)$ des analogen Quellensignals Anteile bis zur Frequenz $f_{\rm NF, \hspace{0.05cm}max}$, so muss für die Abtastrate gelten:

- $$f_{\rm A} = \frac{1}{T_{\rm A} } \ge 2 \cdot f_{\rm NF, \hspace{0.05cm}max} \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- ISDN–Telefonsignale enthalten Spektralanteile zwischen $300 \ \rm Hz$ und $3400 \ \rm Hz$ und die Abtastrate beträgt $f_{\rm A} = 8 \ \rm kHz$ ⇒ $T_{\rm A} = 125 \ \rm µ s$. Somit ist das Abtasttheorem erfüllt.

Wie bereits erwähnt, führt die Quantisierung auf $M$ mögliche Signalwerte zu irreversiblen Fehlern. Wegen der nachfolgenden binären PCM–Codierung wird für $M$ stets eine Zweierpotenz gewählt. Damit lässt sich jeder der $M$–stufigen Eingangswerte durch $N = \log_2 \hspace{0.05cm} (M)$ Binärsymbole (Bit) darstellen.

Bei dieser Dimensionierung ist zu beachten:

- Das Quantisierungs–Signal–zu–Störleistungsverhältnis ist $ρ_{\rm Q} ≈ M^2 = 2^{2N}$. Diese Größe beschreibt das resultierende SNR $ρ_v$ an der Sinke unter der Voraussetzung, dass nicht zusätzlich noch Übertragungsfehler auftreten. Bei Berücksichtigung von Störungen (bzw. Rauschen) ist das Sinken–SNR $ρ_v$ stets kleiner als das Quantisierungs–SNR $ρ_{\rm Q}$.

- Durch große Werte von $M$ bzw. $N$ kann man die PCM–Qualität auf Kosten des Aufwands, der Übertragungsrate und der damit erforderlichen HF–Bandbreite erhöhen. Bei ISDN wurde mit $N = 8$ ⇒ $M = 256$ ein (für die 1990er Jahre) guter Kompromiss zwischen wünschenswerter Qualität und erforderlicher Bitrate standardisiert.

- Die ISDN–Bitrate (für jeden der beiden B–Kanäle) beträgt entsprechend den obigen Angaben $8 · 8000 \ \rm 1/s = 64 \ kbit/s$. Das Quantisierungs-SNR ist somit gleich

- $$\rho_{\rm Q} = 2^{16}\hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} 10 \cdot {\rm lg}\hspace{0.1cm}\rho_{\rm Q}= 10 \cdot {\rm lg}\hspace{0.1cm}2^{16}\approx 48\,{\rm dB} \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- Bei CD–Qualität $(N = 16 \ ⇒ \ M = 65536)$ würde sich $10 · \lg ρ_{\rm Q} ≈ 96 \ \rm dB$ ergeben. Dazu müsste allerdings die Bitrate auf $128 \ \rm kbit/s$ verdoppelt werden.

Betrachten wir nun den grauen Block im PCM-Blockschaltbild. Bei ISDN beinhaltet der Sender keinen Modulator zur Frequenzumsetzung und der Empfänger keinen Demodulator. Das heißt: ISDN ist ein Basisbandübertragungssystem mit folgenden Besonderheiten:

- Beim ISDN–Übertragungssystem wird ein redundantes ternäres Sendesignal $s(t)$ verwendet, wobei auf der $S_0$–Schnittstelle (Hausanschluss) der modifizierte AMI–Code zum Einsatz kommt und auf der $U_{\rm K0}$–Schnittstelle (Zugangsnetz) ein 4B3T–Code.

- Die dominante Störung $n(t)$ ist das Nahnebensprechen von benachbarten Leitungspaaren. Viele der im Buch Digitalsignalübertragung für AWGN–Rauschen angegebenen Aussagen gelten bei dieser Störungsart nur bedingt.

Entstehung und historische Entwicklung

Nachfolgend sind einige Daten zur historischen Entwicklung der digitalen Übertragungstechnik und Vermittlungstechnik – insbesondere von ISDN – zusammengestellt. Hierbei beschränken wir uns vorwiegend auf die Entwicklungen in Deutschland. Weitere Informationen hierüber findet man in [Sie02][2].

- Um 1970 Weltweit wird die Notwendigkeit digitaler Teilnehmeranschlüsse erkannt; dies ist der Anfang der digitalen Übertragungstechnik mit Pulscodemodulation.

- 1979 Entscheidung der Deutschen Bundespost (DBP), alle Vermittlungsstellen zu digitalisieren.

- Um 1980 Erste ISDN–Spezifikation durch Comité Consultatif International Téléphonique et Télégraphique (CCITT) – heute International Telecommunication Union (ITU).

- 1982 Entscheidung der DBP für die Einführung von ISDN und Konkretisierung der Pläne. Bis zur Einführung dauert es aber noch sieben Jahre.

- 1984/85 Die DBP nimmt die ersten digitalen Fern– und Ortsvermittlungsstellen in Betrieb.

- 1987 Start zweier ISDN–Pilotprojekte der DBP in Mannheim und Stuttgart.

- 1989 Offizieller Betriebsbeginn des nationalen ISDN am 08.03. auf der CeBIT in Hannover; Spezifikation eines europaweit einheitlichen ISDN (Euro–ISDN).

- 1993/94 ISDN–Flächendeckung in den alten Ländern der Bundesrepublik Deutschland; Beginn des Breitband–ISDN-Pilotprojekts (ATM) der Deutschen Telekom.

- 1995 Offizielle Einführung des europaweiten ISDN nach dem DSS1–Standard (Euro–ISDN).

- 1996 Einführung des Breitband–ISDN–Regeldienstes.

- 1998 Vollständig digitalisiertes Netz in Deutschland.

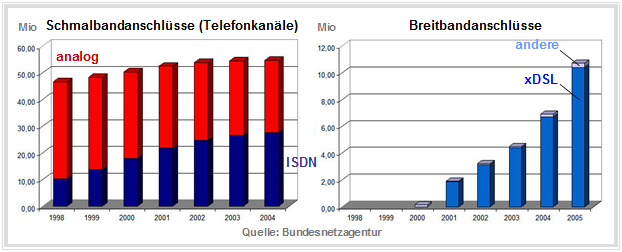

Die linke Grafik zeigt die Zunahme der ISDN–Teilnehmer in Deutschland (blaue Balken).

- Bereits 1999 wird die Zehnmillionen–Marke überschritten und 2002 gibt es schon 20 Millionen ISDN–Teilnehmer in Deutschland.

- Im Jahr 2004 sind schon die Hälfte aller Schmalbandkanäle digital, nachdem die Zahl der analogen Telefonanschlüsse schon ab 2000 deutlich weniger wurden.

- Aus der Grafik kann man aber auch eine gewisse Sättigung (mathematisch ausgedrückt: eine negative zweite Ableitung) der ISDN–Kurve ablesen.

- Dies hängt unmittelbar mit der Erfolgsgeschichte von DSL (Digital Subscriber Line) zusammen, die etwa 2001 beginnt.

Hierzu mehr im zweiten Hauptkapitel dieses Buches.

Aufgaben zum Kapitel

Aufgabe 1.1: ISDN–Versorgungsleitungen

Quellenverzeichnis

- ↑ Pollakowski, M.; Wellhausen, H.W.: Eigenschaften symmetrischer Ortsanschlusskabel im Frequenzbereich bis 30 MHz. Mitteilung aus dem Forschungs- und Technologiezentrum der Deutschen Telekom AG, Darmstadt, Verlag für Wissenschaft und Leben Georg Heidecker, 1995.

- ↑ Siegmund, G.: Technik der Netze. 5. Auflage. Heidelberg: Hüthig, 2002.