Difference between revisions of "Examples of Communication Systems/Methods to Reduce the Bit Error Rate in DSL"

| Line 56: | Line 56: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

Every message system is affected by noise, which usually results primarily from thermal resistance noise. In addition, for a two-wire line, there are: | Every message system is affected by noise, which usually results primarily from thermal resistance noise. In addition, for a two-wire line, there are: | ||

| − | *'''Reflections''': The counter-propagating wave increases the attenuation of a pair of lines, which is taken into account in the [[Linear_and_Time_Invariant_Systems/Some_Results_from_Line_Transmission_Theory#Influence_of_reflections_-_operational_attenuation|"operational attenuation"]] of the line. To prevent such reflection, the terminating resistor $Z_{\rm E}(f)$ would have to be chosen identical to the (complex and frequency-dependent) characteristic impedance $Z_{\rm W}(f)$ . This is difficult in practice. Therefore, the terminating resistors are chosen to be real and constant, and the resulting reflections are combated - if possible - by technical means. | + | *'''Reflections''': The counter-propagating wave increases the attenuation of a pair of lines, which is taken into account in the [[Linear_and_Time_Invariant_Systems/Some_Results_from_Line_Transmission_Theory#Influence_of_reflections_-_operational_attenuation|"operational attenuation"]] of the line. To prevent such reflection, the terminating resistor $Z_{\rm E}(f)$ would have to be chosen identical to the (complex and frequency-dependent) characteristic impedance $Z_{\rm W}(f)$ . This is difficult in practice. Therefore, the terminating resistors are chosen to be real and constant, and the resulting reflections are combated - if possible - by technical means. |

*'''Crosstalk''': This is dominant interference in conducted transmission. Crosstalk occurs when inductive and capacitive couplings between adjacent cores of a cable bundle cause mutual interference during signal transmission. | *'''Crosstalk''': This is dominant interference in conducted transmission. Crosstalk occurs when inductive and capacitive couplings between adjacent cores of a cable bundle cause mutual interference during signal transmission. | ||

| Line 131: | Line 131: | ||

*From a line length of around 1800 meters, on the other hand, ADSL2+ is significantly better than VDSL(2). | *From a line length of around 1800 meters, on the other hand, ADSL2+ is significantly better than VDSL(2). | ||

*This is due to the fact that VDSL(2) operates in the lower frequency bands with significantly lower transmission power in order to interfere less with neighboring transmission systems. | *This is due to the fact that VDSL(2) operates in the lower frequency bands with significantly lower transmission power in order to interfere less with neighboring transmission systems. | ||

| − | *As the line length increases, the higher frequency subchannels become unusable for data transmission due to increasing attenuation, which explains the crash in the data rate}} | + | *As the line length increases, the higher frequency subchannels become unusable for data transmission due to increasing attenuation, which explains the crash in the data rate.}} |

| Line 144: | Line 144: | ||

In the DMT method, two paths are implemented for error correction measures in the signal processors. The bit assignment to these paths is done by a multiplexer with sync control. | In the DMT method, two paths are implemented for error correction measures in the signal processors. The bit assignment to these paths is done by a multiplexer with sync control. | ||

*In the case of the ''Fast Path'', low waiting times (''latency'') are used. | *In the case of the ''Fast Path'', low waiting times (''latency'') are used. | ||

| − | *With '''Interleaved-Path | + | *With '''Interleaved-Path''' low bit error rates are in the foreground. Here the latency is higher due to the use of an interleaver. |

*A dual latency means the simultaneous use of both paths. The ''ADSL Transceiver Units'' must support dual latency at least in the downstream. | *A dual latency means the simultaneous use of both paths. The ''ADSL Transceiver Units'' must support dual latency at least in the downstream. | ||

<br clear=all> | <br clear=all> | ||

| Line 157: | Line 157: | ||

| − | ==Cyclic | + | ==Cyclic redundancy check== |

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | + | The ''cyclic redundancy check'' (CRC) is a simple bit-level procedure to check the integrity of data during transmission or duplication. The CRC principle has already been described in detail in the [[Examples_of_Communication_Systems/ISDN_Primary_Multiplex_Connection#Frame_synchronization|"ISDN chapter"]] . | |

| − | + | Here follows a brief summary, using the nomenclature used in xDSL specifications: | |

| − | * | + | *Prior to data transmission, for a data block $D(x)$ with $k$ bit ⇒ $d_0$, ... , $d_{k-1}$ a parity-check value $C(x)$ with eight bits is formed and appended to the original data sequence. The variable $x$ here denotes a delay operator. |

| − | *$C(x)$ | + | *$C(x)$ is obtained as the division remainder of the polynomial division of $D(x)$ by the parity-check polynomial $G(x)$. This operation is described by modulo-2 equations: |

:$$D(x) = d_0 \cdot x^{k-1} + d_1 \cdot x^{k-2} + ... + d_{k-2} \cdot x + d_{k-1}\hspace{0.05cm},$$ | :$$D(x) = d_0 \cdot x^{k-1} + d_1 \cdot x^{k-2} + ... + d_{k-2} \cdot x + d_{k-1}\hspace{0.05cm},$$ | ||

:$$G(x) = x^8 + x^4 + x^3 + x^2 + 1 \hspace{0.05cm},$$ | :$$G(x) = x^8 + x^4 + x^3 + x^2 + 1 \hspace{0.05cm},$$ | ||

| Line 169: | Line 169: | ||

\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | \hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| − | * | + | *At the receiver, a CRC value is formed again using the same procedure and compared with the transmitted check value. If both are unequal, at least one bit error is present. |

| − | * | + | *This way, bit errors can be detected if they are not too clustered. In ADSL practice, the CRC procedure is sufficient for bit error detection. |

| − | [[File:P_ID1968__Bei_T_2_4_S5_v1.png|center|frame|CRC | + | [[File:P_ID1968__Bei_T_2_4_S5_v1.png|center|frame|CRC parity-check value generation for ADSL]] |

| − | + | The graphic shows an exemplary circuit - realizable in hardware or software - for CRC parity-check value generation with the generator polynomial specified for ADSL $G(x)$: | |

| − | * | + | *The data block to be tested is introduced into the circuit from the left, the output is fed back and exclusively-or-linked to the digits of the generator polynomial $G(x)$ . After passing through the entire data block, the memory elements contain the CRC parity-check value $C(x)$. |

| − | * | + | *It should be noted in this context that with ADSL the data is split into so-called superframes (of 68 frames each). Each frame contains data from the fast and interleaved path. In addition, management and synchronization bits are transmitted in specific frames. |

| − | * | + | *Eight CRC bits are formed per ADSL superframe and per path and are transmitted as ''Fast Byte'' and ''Sync Byte'' respectively, as the first byte of frame $0$ of the next superframe. |

| − | ==Scrambler | + | ==Scrambler and De–Scrambler== |

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | + | The task of the scrambler is to convert long sequences of ones and zeros in such a way that frequent symbol changes occur. | |

| − | * | + | *A possible realization is a shift register circuit with feedback exclusive-or-linked branches. |

| − | * | + | *In order to produce the original binary sequence at the receiver, a mirror-image self-synchronizing de-scrambler must be used there. |

| − | + | The graphic shows on the left an example of a scrambler actually used at DSL with 23 memory elements. The corresponding de-scrambler is shown on the right. | |

| − | [[File:P_ID1960__Bei_T_2_4_S6a.png|center|frame|Scrambler | + | [[File:P_ID1960__Bei_T_2_4_S6a.png|center|frame|Scrambler and De-Scrambler in a DSL/DMT system]] |

| − | + | The transmision side shift register is loaded with an arbitrary initial value that has no further effect on the operation of the circuit. If we denote by $e_n$ the bits of the binary input sequence and by $a_n$ the bits at the output, the following relation holds: | |

| − | :$$a_n = | + | :$$a_n = e_n \oplus a_{n- 18}\oplus a_{n- 23}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ |

| − | + | In the example, the input sequence consists of 80 consecutive ones (upper left gray background), which are shifted bit by bit into the scrambler. The output bit sequence then has frequent one-zero changes, as desired. | |

| − | + | The de-scrambler (shown on the right) can be started at any time. The output data stream shows, | |

| − | * | + | *that the de-scrambler initially outputs some (up to a maximum of 23) erroneous bits, |

| − | * | + | but *then synchronizes automatically and |

| − | * | + | *then recovers the original bit sequence (only ones) without errors. |

| − | + | Note that for this example, although the bit transfer was assumed to be error-free, the de-scrambler can also be loaded with any starting value, which means that no synchronization is required between the two circuits. | |

| − | == | + | ==Forward error correction== |

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | Zur Vorwärtsfehlerkorrektur (''Forward Error Correction'', FEC) wird bei allen xDSL–Varianten ein [[ | + | Zur Vorwärtsfehlerkorrektur (''Forward Error Correction'', FEC) wird bei allen xDSL–Varianten ein [[Channel_Coding/Definition_and_Properties_of_Reed-Solomon_Codes|"Reed–Solomon–Code"]] (RS–Codierung) verwendet. Bei manchen Systemen – beispielsweise bei ADSL der Deutschen Telekom – wurde als zusätzliche Fehlerschutzmaßnahme ''Trellis Code Modulation'' (TCM) verbindlich festgelegt, auch wenn diese von den internationalen Gremien nur als „optional” spezifiziert wurde. |

| − | Beide Verfahren werden im Buch [[ | + | Beide Verfahren werden im Buch "[[Channel_Coding]]" ausführlich behandelt. Hier folgt eine kurze Zusammenfassung der Reed–Solomon–Codierung im Hinblick auf die Anwendung bei DSL: |

*Mit der Reed–Solomon–Codierung werden Redundanz–Bytes für fest vereinbarte Stützstellen des Nutzdatenpolynoms generiert. Bei systematischer RS–Codierung wird ähnlich dem CRC–Verfahren ein Prüfwert berechnet und an den zu schützenden Datenblock angehängt. | *Mit der Reed–Solomon–Codierung werden Redundanz–Bytes für fest vereinbarte Stützstellen des Nutzdatenpolynoms generiert. Bei systematischer RS–Codierung wird ähnlich dem CRC–Verfahren ein Prüfwert berechnet und an den zu schützenden Datenblock angehängt. | ||

*Die Daten werden jedoch nicht mehr bitweise, sondern byteweise verarbeitet. Demzufolge werden arithmetische Operationen nicht mehr im Galois–Feld $\rm GF( 2 )$ ausgeführt, sondern in $\rm GF(2^8)$. | *Die Daten werden jedoch nicht mehr bitweise, sondern byteweise verarbeitet. Demzufolge werden arithmetische Operationen nicht mehr im Galois–Feld $\rm GF( 2 )$ ausgeführt, sondern in $\rm GF(2^8)$. | ||

| Line 226: | Line 226: | ||

Die Besonderheiten der Reed–Solomon–Codierung bei xDSL werden hier ohne weitere Kommentierung angegeben: | Die Besonderheiten der Reed–Solomon–Codierung bei xDSL werden hier ohne weitere Kommentierung angegeben: | ||

*Bei xDSL muss die Anzahl $R$ der Prüfbytes ein ganzzahliges Vielfaches der Symbolanzahl $S$ sein, damit diese im Nutzdatenpolynom gleichmäßig verteilt werden können. | *Bei xDSL muss die Anzahl $R$ der Prüfbytes ein ganzzahliges Vielfaches der Symbolanzahl $S$ sein, damit diese im Nutzdatenpolynom gleichmäßig verteilt werden können. | ||

| − | *Die so genannten [https:// | + | *Die so genannten [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Singleton_bound#MDS_codes "MDS–Codes"] (''Maximum Distance Separable'') – eine Unterklasse der RS–Codes – erlauben die Korrektur von $R/2$ verfälschten Nutzdatenbytes. |

*Vom gewählten Reed–Solomon–Code für die DMT–Systeme ergibt sich als Einschränkung eine maximale Codewortlänge von $2^8–1 = 255$ Byte entsprechend $2040$ Bit. | *Vom gewählten Reed–Solomon–Code für die DMT–Systeme ergibt sich als Einschränkung eine maximale Codewortlänge von $2^8–1 = 255$ Byte entsprechend $2040$ Bit. | ||

*Die Redundanz der Reed–Solomon–Codes kann bei ungünstigen Codeparametern eine beachtliche Datenmenge erzeugen, wodurch die Nettoübertragungsrate erheblich geschmälert wird. | *Die Redundanz der Reed–Solomon–Codes kann bei ungünstigen Codeparametern eine beachtliche Datenmenge erzeugen, wodurch die Nettoübertragungsrate erheblich geschmälert wird. | ||

Revision as of 20:55, 10 March 2023

Contents

- 1 Transmission properties of copper cables

- 2 Noise during transmission

- 3 Signal–to–noise ratio, range and transmission rate

- 4 DSL error correction measures at a glance

- 5 Cyclic redundancy check

- 6 Scrambler and De–Scrambler

- 7 Forward error correction

- 8 Interleaving und De–Interleaving

- 9 Gain Scaling und Tone Ordering

- 10 Einfügen von Guard–Intervall und zyklischem Präfix

- 11 Aufgaben zum Kapitel

- 12 Quellenverzeichnis

Transmission properties of copper cables

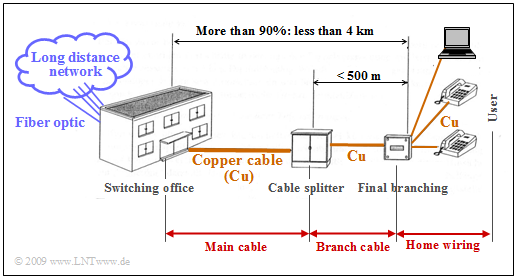

As already mentioned in the chapter "General Description of DSL" , the telephone line network of Deutsche Telekom mainly uses balanced copper pairs with a diameter of $\text{0.4 mm}$ . The last mile is divided into three segments:

- the main cable,

- the branch cable,

- the house connection cable.

On average, the line length is less than four kilometers. In cities, the copper line is shorter than $90\%$ of all cases $\text{2.8 km}$.

The $\rm xDSL$ variants discussed here were developed specifically for use on such symmetrical balanced copper pairs in the cable network. In order to better understand the technical requirements for the xDSL systems, a closer look must be taken at the transmission characteristics and interference on the conductor pairs. This topic has already been dealt with in detail in the fourth main chapter Properties of Electrical Lines of the book "Linear and Time Invariant Systems" and is therefore only briefly summarized here using the "equivalent circuit" :

- Line transmission properties are fully characterized by the characteristic impedance $Z_{\rm W}(f)$ and the transmission coefficient $γ(f)$ . Both quantities are generally complex.

- The attenuation coefficient $α(f)$ is the real part of the transmission measure and describes the damping of the wave propagating along the line; $α(f)$ is an even function of frequency.

- The odd imaginary part $β(f)$ of the complex transmission measure is called phase coefficient and gives the phase rotation of the signal wave along the line.

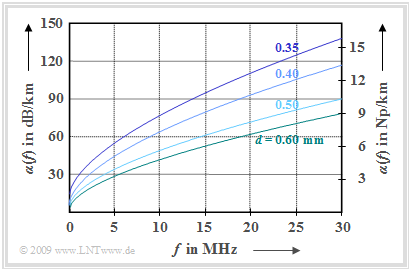

$\text{Example 1:}$ As an example, we consider the attenuation coefficient shown on the right, which is based on empirical investigations by Deutsche Telekom.

The curves were obtained by averaging over a large number of measured lines of one kilometer length in the frequency range up to $\text{30 MHz}$. One can see:

- The attenuation coefficient $α(f)$ increases approximately proportionally with the square root of the frequency and decreases with increasing conductor diameter $d$ .

- The attenuation function $a(f)$ increases linearly with cable length $l$ :

- $$a(f) = α(f) · l.$$

Note the difference between

- "$a$" (for the attenuation function) and

- "$alpha$" (for the attenuation coefficient, with respect to length).

For the line diameter $\text{0.4 mm}$ was given in [PW95][1] an empirical approximation formula for the attenuation coefficient given:

- $$\alpha(f) = \left [ 5.1 + 14.3 \cdot \left (\frac{f}{\rm 1\,MHz}\right )^{0.59} \right ] \frac{\rm dB}{\rm km} \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

Evaluating this equation, the following exemplary values can be given:

- The attenuation $a(f)$ of a balanced copper wire of length $l = 1 \ \rm km$ with diameter $0.4 \ \rm mm$ is slightly more than $60\ \rm dB$ for signal frequency $10\ \rm MHz$ .

- At twice the frequency $(20 \ \rm MHz)$ the attenuation value increases to over $90 \ \rm dB$. It can be seen that the attenuation does not increase exactly with the root of the frequency, as would be the case if the skin effect were considered alone, since several other effects also contribute to the attenuation.

- If the cable length is doubled to $l = 2 \ \rm km$ the attenuation reaches a value of more than $120 \ \rm dB$ $($at $10 \ \rm MHz)$, which corresponds to an amplitude attenuation factor smaller than $10^{-6}$ .

- Due to the frequency dependence of $α(f)$ and $β(f)$ both intersymbol interference $\rm (ISI)$ and inter–carrier–interference $\rm (ICI)$ occur. Suitable equalization must therefore be provided for xDSL.

In the chapter "Properties of balanced copper pairs" of the book "Linear Time-Invariant Systems" this topic is treated in detail. We refer to the two interactive applets "Attenuation of copper cables" and "Time behavior of copper cables".

Noise during transmission

Every message system is affected by noise, which usually results primarily from thermal resistance noise. In addition, for a two-wire line, there are:

- Reflections: The counter-propagating wave increases the attenuation of a pair of lines, which is taken into account in the "operational attenuation" of the line. To prevent such reflection, the terminating resistor $Z_{\rm E}(f)$ would have to be chosen identical to the (complex and frequency-dependent) characteristic impedance $Z_{\rm W}(f)$ . This is difficult in practice. Therefore, the terminating resistors are chosen to be real and constant, and the resulting reflections are combated - if possible - by technical means.

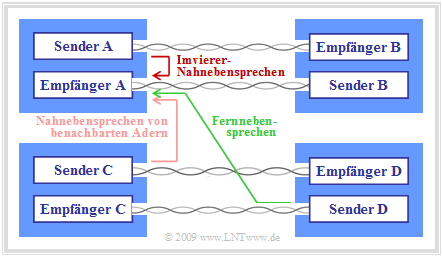

- Crosstalk: This is dominant interference in conducted transmission. Crosstalk occurs when inductive and capacitive couplings between adjacent cores of a cable bundle cause mutual interference during signal transmission.

Crosstalk is divided into two types (see graphic):

- Near End Crosstalk (NEXT): The interfering transmitter and the interfered receiver are on the same side of the cable.

- Far End Crosstalk (FEXT): The interfering transmitter and the interfered receiver are on opposite sides of the cable.

Far-end crosstalk decreases sharply with increasing cable length due to attenuation, so that near-end crosstalk is dominant even with DSL.

$\text{Conclusion:}$ To summarize:

- As frequency increases and spacing between pairs of conductors decreases - as within a star quad - near-end crosstalk increases. It is less critical if the conductors are in different basic bundles.

- Depending on the stranding technique used, the shielding and the manufacturing accuracy of the cable, this effect occurs to varying degrees. The cable length, on the other hand, does not play a role in near-end crosstalk: The own transmitter is not attenuated by the cable.

- Crosstalk can be significantly reduced by clever assignment, for example by assigning different services to adjacent pairs, using different frequency bands with as little overlap as possible.

Signal–to–noise ratio, range and transmission rate

To evaluate the quality of a transmission system, the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) is usually used before the decision maker. This is also a measure of the expected bit error rate (BER).

- Signal and noise in the same frequency band reduce the SNR and lead to a higher bit error rate or - for a given bit error rate - to a lower transmission rate.

- The relationships between transmit power, channel quality (cable attenuation and interference power Korrektur ( noise power?) ) and achievable transmission rate can be illustrated very well by Shannon's channel capacity formula:

- $$C \left [ \frac{\rm bit}{\rm Symbol} \right ] = \frac {1}{2} \cdot \log_2 \left ( 1 + \frac{P_{\rm E}}{P_{\rm N}} \right )= \frac {1}{2} \cdot \log_2 \left ( 1 + \frac{\alpha_{\rm K}^2 \cdot P_{\rm S}}{P_{\rm N}} \right ) \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

The channel capacity $C$ denotes the maximum transmission bit rate at which transmission is possible under ideal conditions (among others, the best possible coding with infinite block length) ⇒ channel coding theorem. For more details, see the fourth main chapter Continuous-Value Information Theory of the book "Information Theory".

We assume that the bandwidth is fixed by the xDSL variant and that near-end crosstalk is the dominant interference. Then the transmission rate can be improved by the following measures:

- For a given transmit power $P_{\rm S}$ and a given medium (for example: balanced copper pairs with 0.4 mm diameter), the receive power that can be used for demodulation $P_{\rm E}$ is increased only by a shorter line length.

- One reduces the interference power $P_{\rm N}$, which for a given bandwidth $B$ would be achieved by increased crosstalk attenuation, which in turn also depends on the transmission method on the adjacent line pairs.

- Increasing the transmit power $P_{\rm S}$ would not be effective here, since a larger transmit power would at the same time have an unfavorable effect on the crosstalk. This measure would only be successful for an AWGN channel (example: coaxial cable).

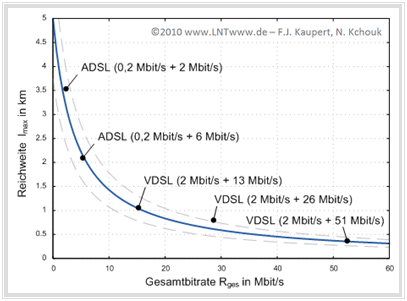

This listing shows that with xDSL there is a direct correlation between range (line length), transmission rate and the transmission method used. From the following graph, which refers to measurements with 1-DA xDSL methods and 0.4mm copper cables in test systems with realistic interference conditions, one can clearly see these dependencies.

$\text{Example 2:}$ The graph shows

- the range (maximum cable length) $l_{\rm max}$ and

- the total transmission rate $R_{\rm ges}$ of upstream (first indication)

and downstream (second indication).

for some ADSL and VDSL variants.

The total transmission rate for the systems considered is between $2.2 \ \rm Mbit/s$ and $53\ \rm Mbit/s$. The range here refers to a copper twisted pair with 0.4 mm diameter.

The trend of the measured values is shown in this graph as a solid (blue) curve and can be formulated as a rough approximation as follows:

- $$l_{\rm max}\,{\rm \big [in}\,\,{\rm km \big ] } = \frac {20}{4 + R_{\rm ges}\,{\rm \big [in}\,\,{\rm Mbit/s \big ] } } \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

It can be seen that the range of all current systems (approximately between half a kilometer and three and a half kilometers of line length) differs from this rule of thumb by a maximum of $±25\%$ (dashed curves).

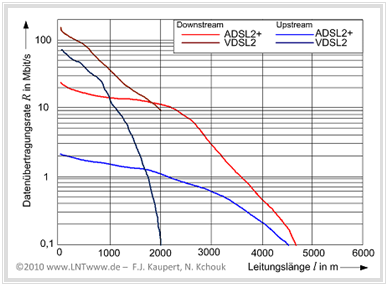

$\text{Example 3:}$ The diagram below shows the total data transmission rates of ADSL2+ and VDSL(2) as a function of line length, with the (different) red curves referring to the downstream and the two blue curves to the upstream. This is based on a worst-case interference scenario with the following boundary conditions:

- Cable bundle with 50 copper pairs (0.4 mm diameter), PE insulated,

- target symbol error rate $10^{-7}, 6 \ \text{dB}$ margin (reserve SNR to reach target data rate),

- simultaneous operation of the following transmission methods:

- 25 times ADSL2+ over ISDN,

- 14 times ISDN, four times SHDSL (1 Mbit/s),

- five times each SHDSL (2 Mbit/s) and VDSL2 band plan 998, and

- twice HDSL.

You can see from this diagram:

- For short line lengths, the achievable transmission rates for VDSL(2) are significantly higher than for ADSL2+.

- From a line length of around 1800 meters, on the other hand, ADSL2+ is significantly better than VDSL(2).

- This is due to the fact that VDSL(2) operates in the lower frequency bands with significantly lower transmission power in order to interfere less with neighboring transmission systems.

- As the line length increases, the higher frequency subchannels become unusable for data transmission due to increasing attenuation, which explains the crash in the data rate.

DSL error correction measures at a glance

In order to reduce the bit error rate of xDSL systems, a number of techniques have been cleverly combined in the specifications to counteract the two most common causes of errors:

- Transmission errors due to impulse and crosstalk interference on the line:

Besonders bei hohen Datenraten liegen benachbarte Symbole im QAM–Signalraum eng beieinander, was die Fehlerwahrscheinlichkeit signifikant erhöht. - Cutting off of signal peaks due to lack of dynamic range of the transmission amplifiers (clipping):

This clipping also corresponds to impulse noise and acts as an additional colored noise load that noticeably degrades the SNR.

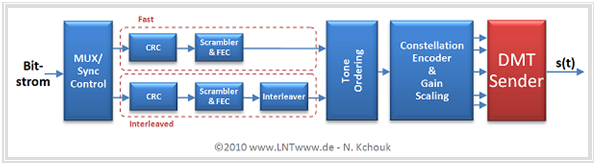

In the DMT method, two paths are implemented for error correction measures in the signal processors. The bit assignment to these paths is done by a multiplexer with sync control.

- In the case of the Fast Path, low waiting times (latency) are used.

- With Interleaved-Path low bit error rates are in the foreground. Here the latency is higher due to the use of an interleaver.

- A dual latency means the simultaneous use of both paths. The ADSL Transceiver Units must support dual latency at least in the downstream.

The remaining chapter pages discuss error protection procedures for both paths.

(For other modulation methods, the error protection measures described are the same in principle, but different in detail).

- The transmission chain starts with the Cyclic Redundancy Check (CRC), which forms a checksum over an overframe that is evaluated at the receiver.

- The task of the scrambler is to convert long sequences of ones and zeros to produce more frequent signal changes.

- This is followed by forward error correction (FEC) to detect and possibly correct byte errors at the receiving end.

The standard for xDSL is Reed-Solomon coding, often Trellis coding is also used. - The task of the interleaver is to distribute the received codewords over a larger time range in order to also distribute any transmission interference that may occur over several codewords and thus increase the chances of reconstruction.

- After passing through the individual bit protection procedures, the data streams from the Fast and Interleaved paths are combined and processed in Tone Ordering . Here the bits are also assigned to the carrier frequencies (bins).

- In addition, a guard interval and cyclic prefix are inserted in the DMT transmitter after the IDFT, which is removed again in the DMT receiver. This represents a very simple realization of signal equalization in the frequency domain when the channel is distorted.

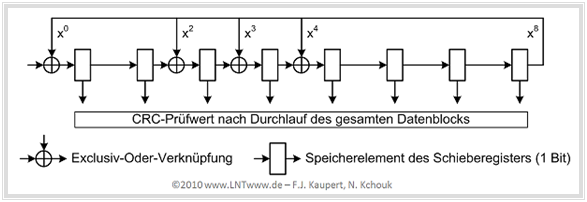

Cyclic redundancy check

The cyclic redundancy check (CRC) is a simple bit-level procedure to check the integrity of data during transmission or duplication. The CRC principle has already been described in detail in the "ISDN chapter" .

Here follows a brief summary, using the nomenclature used in xDSL specifications:

- Prior to data transmission, for a data block $D(x)$ with $k$ bit ⇒ $d_0$, ... , $d_{k-1}$ a parity-check value $C(x)$ with eight bits is formed and appended to the original data sequence. The variable $x$ here denotes a delay operator.

- $C(x)$ is obtained as the division remainder of the polynomial division of $D(x)$ by the parity-check polynomial $G(x)$. This operation is described by modulo-2 equations:

- $$D(x) = d_0 \cdot x^{k-1} + d_1 \cdot x^{k-2} + ... + d_{k-2} \cdot x + d_{k-1}\hspace{0.05cm},$$

- $$G(x) = x^8 + x^4 + x^3 + x^2 + 1 \hspace{0.05cm},$$

- $$C(x) = D(x) \cdot x^8 \,\,{\rm mod }\,\, G(x) = c_0 \cdot x^7 + c_1 \cdot x^6 + \text{...} + c_6 \cdot x + c_7 \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- At the receiver, a CRC value is formed again using the same procedure and compared with the transmitted check value. If both are unequal, at least one bit error is present.

- This way, bit errors can be detected if they are not too clustered. In ADSL practice, the CRC procedure is sufficient for bit error detection.

The graphic shows an exemplary circuit - realizable in hardware or software - for CRC parity-check value generation with the generator polynomial specified for ADSL $G(x)$:

- The data block to be tested is introduced into the circuit from the left, the output is fed back and exclusively-or-linked to the digits of the generator polynomial $G(x)$ . After passing through the entire data block, the memory elements contain the CRC parity-check value $C(x)$.

- It should be noted in this context that with ADSL the data is split into so-called superframes (of 68 frames each). Each frame contains data from the fast and interleaved path. In addition, management and synchronization bits are transmitted in specific frames.

- Eight CRC bits are formed per ADSL superframe and per path and are transmitted as Fast Byte and Sync Byte respectively, as the first byte of frame $0$ of the next superframe.

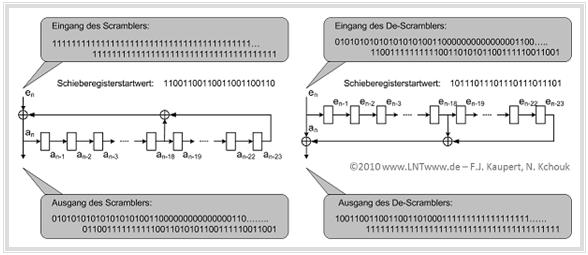

Scrambler and De–Scrambler

The task of the scrambler is to convert long sequences of ones and zeros in such a way that frequent symbol changes occur.

- A possible realization is a shift register circuit with feedback exclusive-or-linked branches.

- In order to produce the original binary sequence at the receiver, a mirror-image self-synchronizing de-scrambler must be used there.

The graphic shows on the left an example of a scrambler actually used at DSL with 23 memory elements. The corresponding de-scrambler is shown on the right.

The transmision side shift register is loaded with an arbitrary initial value that has no further effect on the operation of the circuit. If we denote by $e_n$ the bits of the binary input sequence and by $a_n$ the bits at the output, the following relation holds:

- $$a_n = e_n \oplus a_{n- 18}\oplus a_{n- 23}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

In the example, the input sequence consists of 80 consecutive ones (upper left gray background), which are shifted bit by bit into the scrambler. The output bit sequence then has frequent one-zero changes, as desired.

The de-scrambler (shown on the right) can be started at any time. The output data stream shows,

- that the de-scrambler initially outputs some (up to a maximum of 23) erroneous bits,

but *then synchronizes automatically and

- then recovers the original bit sequence (only ones) without errors.

Note that for this example, although the bit transfer was assumed to be error-free, the de-scrambler can also be loaded with any starting value, which means that no synchronization is required between the two circuits.

Forward error correction

Zur Vorwärtsfehlerkorrektur (Forward Error Correction, FEC) wird bei allen xDSL–Varianten ein "Reed–Solomon–Code" (RS–Codierung) verwendet. Bei manchen Systemen – beispielsweise bei ADSL der Deutschen Telekom – wurde als zusätzliche Fehlerschutzmaßnahme Trellis Code Modulation (TCM) verbindlich festgelegt, auch wenn diese von den internationalen Gremien nur als „optional” spezifiziert wurde.

Beide Verfahren werden im Buch "Channel Coding" ausführlich behandelt. Hier folgt eine kurze Zusammenfassung der Reed–Solomon–Codierung im Hinblick auf die Anwendung bei DSL:

- Mit der Reed–Solomon–Codierung werden Redundanz–Bytes für fest vereinbarte Stützstellen des Nutzdatenpolynoms generiert. Bei systematischer RS–Codierung wird ähnlich dem CRC–Verfahren ein Prüfwert berechnet und an den zu schützenden Datenblock angehängt.

- Die Daten werden jedoch nicht mehr bitweise, sondern byteweise verarbeitet. Demzufolge werden arithmetische Operationen nicht mehr im Galois–Feld $\rm GF( 2 )$ ausgeführt, sondern in $\rm GF(2^8)$.

Die Reed–Solomon–Prüfziffer lässt sich auch als Divisionsrest einer Polynomdivision ermitteln, bei xDSL mit folgenden Parametern:

- Anzahl $S$ der zu überwachenden DMT–Symbole pro Reed–Solomon–Codewort $(S \ge 1$ für den Fast–Puffer, $S =2^0$, ... , $2^4$ für den Interleaved–Puffer$)$,

- Anzahl $K$ der Nutzdatenbytes in den $S$ DMT–Symbolen, definiert als Polynom $B(x)$ vom Grad $K$, wobei das „B” auf Bytes hinweist,

- Anzahl $R$ der RS–Prüfbytes $($gerade Zahl zwischen $2$ bis $16)$ pro Prüfwert ("Fast" oder "Interleaved"),

- Summe $N = K + R$ der Nutzdatenbytes und Prüfbytes des Reed–Solomon–Codewortes.

Die Besonderheiten der Reed–Solomon–Codierung bei xDSL werden hier ohne weitere Kommentierung angegeben:

- Bei xDSL muss die Anzahl $R$ der Prüfbytes ein ganzzahliges Vielfaches der Symbolanzahl $S$ sein, damit diese im Nutzdatenpolynom gleichmäßig verteilt werden können.

- Die so genannten "MDS–Codes" (Maximum Distance Separable) – eine Unterklasse der RS–Codes – erlauben die Korrektur von $R/2$ verfälschten Nutzdatenbytes.

- Vom gewählten Reed–Solomon–Code für die DMT–Systeme ergibt sich als Einschränkung eine maximale Codewortlänge von $2^8–1 = 255$ Byte entsprechend $2040$ Bit.

- Die Redundanz der Reed–Solomon–Codes kann bei ungünstigen Codeparametern eine beachtliche Datenmenge erzeugen, wodurch die Nettoübertragungsrate erheblich geschmälert wird.

- Es empfiehlt sich eine sinnvolle Aufteilung der Datenübertragungsmenge (Bruttodatenrate) in Nutzdaten (Nettodatenrate, Payload) und Fehlerschutzdaten (Overhead).

- Die Reed–Solomon–Codierung erzielt einen hohen Codiergewinn. Ein System ohne Codierung müsste für die gleiche Bitfehlerrate ein um $3 \ \rm dB$ größeres SNR aufweisen.

- Durch die Trellis–codierte Modulation (TCM) in Verbindung mit den anderen Fehlerschutzmaßnahmen fällt der Codiergewinnn höchst unterschiedlich aus; er bewegt sich zwischen $0 \ \rm dB$ und $6 \ \rm dB$.

Interleaving und De–Interleaving

Gemeinsame Aufgabe von Interleaver (beim Sender) und De–Interleaver (beim Empfänger) ist es, die empfangenen Reed–Solomon–Codewörter über einen größeren Zeitbereich zu verteilen, um eventuell auftretende Übertragungsfehler auf mehrere Codeworte zu verteilen und damit die Chance einer korrekten Decodierung zu erhöhen.

Das Interleaving ist durch den Parameter $D$ ("Tiefe") charakterisiert, der Werte zwischen $2^0$ und $2^9$ annehmen kann.

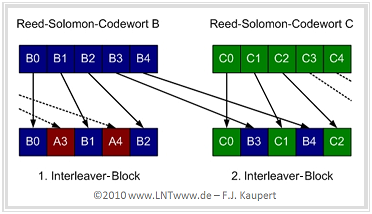

$\text{Beispiel 4:}$ Die Grafik verdeutlicht das Prinzip anhand der Reed–Solomon–Codeworte $A$, $B$, $C$ mit jeweils fünf Byte sowie der Interleaver–Tiefe $D = 2$.

Jedes Byte $B_i$ des mittleren Reed–Solomon–Codewortes $B$ wird um $V_i = (D - 1) · i$ Bytes verzögert und es werden zwei Interleaver–Blöcke gebildet:

- Im ersten Block sind die Bytes $B_0$, $B_1$ und $B_2$ zusammen mit den Bytes $A_3$ und $A_4$ des vorherigen Codewortes zusammengefasst.

- Der zweite Block beinhaltet die Bytes $B_3$ und $B_4$ zusammen mit den Bytes $C_0$, $C_1$ und $C_2$ des nachfolgenden Codewortes.

Diese "Verwürfelung" hat folgende Vorteile (vorausgesetzt, $D$ ist hinreichend groß):

- Die Fehlerkorrekturmöglichkeiten des Reed–Solomon–Codes werden verbessert.

- Die Nutzdatenrate bleibt gleich, wird also nicht vermindert (Redundanzfreiheit).

- Bei Störungen müssen nicht ganze Pakete auf Protokollebene wiederholt werden.

Nachteilig ist, dass es mit zunehmender Interleaver–Tiefe $D$ zu merklichen Verzögerungszeiten (in der Größenordnung von Millisekunden) kommen kann, was für Echtzeitanwendungen große Probleme bereitet. Interleaving mit geringer Tiefe ist allerdings nur bei genügend hohem Signal–zu–Rausch–Abstand sinnvoll.

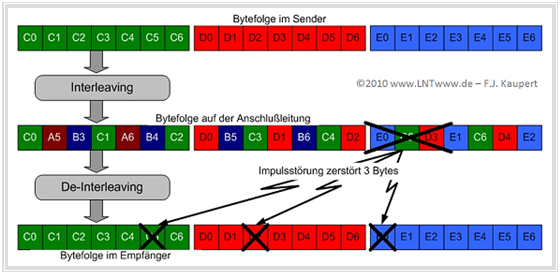

$\text{Beispiel 5:}$ Ein Beispiel für die Vorteile von Interleaver/De–Interleaver bei Vorhandensein von Bündelfehlern zeigt die untere Grafik:

- In der ersten Zeile sind die Bytefolgen nach der Reed–Solomon–Codierung dargestellt, wobei jedes Codeworte beispielhaft aus sieben Bytes besteht.

- In der mittleren Zeile werden die Datenbytes durch das Interleaving mit $D = 3$ verschoben, sodass zwischen $C_i$ und $C_{i+1}$ zwei fremde Bytes liegen und das Codewort auf drei Blöcke verteilt wird.

- Es sei nun angenommen, dass während der Übertragung eine Impulsstörung drei aufeinander folgende Bytes in einem einzigen Datenblock verfälscht wurden.

- Nach dem De–Interleaver ist die ursprüngliche Bytefolge der Reed–Solomon–Codewörter wieder hergestellt, wobei die drei fehlerhaften Bytes auf drei unabhängige Codewörter verteilt sind.

- Wurden bei der Reed–Solomon–Codierung jeweils zwei Redundanzbytes eingefügt, so lassen sich die nun separierten Byteverfälschungen vollständig korrigieren.

Gain Scaling und Tone Ordering

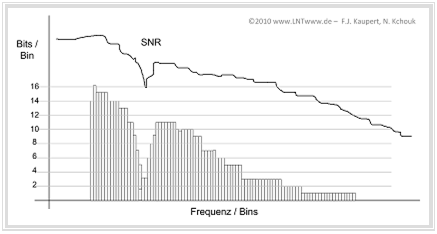

Eine besonders vorteilhafte Eigenschaft von DMT ist die Möglichkeit, die Subkanäle (englisch: Bins) individuell an die vorliegende Kanalcharakteristik anzupassen und eventuell "Bins" mit ungünstigem SNR ganz abzuschalten. Dabei wird wie folgt vorgegangen:

- Vor dem Start der Übertragung – und eventuell auch dynamisch während des Betriebs – wird vom DMT–Modem für jeden "Bin" die Kanalcharakteristik gemessen und entsprechend dem SNR individuell die maximale Übertragungsrate festgelegt (siehe Grafik).

- Während der Initialisierung tauschen die ADSL Transceiver Units Bin–Informationen aus, zum Beispiel die jeweiligen „Bits/Bin” und die erforderliche Sendeleistung (Gain). Dabei sendet die $\rm ATU–C$ Informationen über den Upstream und die $\rm ATU–R$ Informationen über den Downstream.

- Diese Mitteilung hat die Form $\{b_i, g_i\}$ wobei $b_i$ (4 Bit) die Größe der Konstellation angibt. Für den Upstream gilt für den Index $i = 1$, ... , $31$ und für den Downstream $i = 1$, ... , $255$.

- Der Gain $g_i$ ist eine Festkommazahl mit zwölf Bit. Beispielsweise steht $g_i = 001.010000000$ für den Dezimalwert $1 + 1/4 =1.25$. Dieser gibt an, dass die Signalleistung von Kanal $i$ um $1.94 \ \rm dB$ höher sein muss als die Leistung des während der Kanalanalyze gesendeten Testsignals.

Beim gleichzeitigen Betrieb des Fast– und des Interleaved–Pfades (siehe Grafik auf der Seite "DSL–Fehlerkorrekturmaßnahmen") kann durch eine optimierte Trägerfrequenzbelegung (Tone Ordering) die Bitfehlerrate weiter gesenkt werden. Hintergrund dieser Maßnahme ist wieder das Clipping (Abschneiden von Spannungsspitzen), wodurch das SNR insgesamt verschlechtert wird. Dieses Verfahren beruht auf folgenden Regeln:

- Bins mit dichter Konstellation (viele Bits/Bin ⇒ größere Verfälschungswahrscheinlichkeit) werden dem Interleaved–Zweig zugeordnet, da dieser durch den zusätzlichen Interleaver per se zuverlässiger ist. Entsprechend werden die Subkanäle mit niederwertiger Belegung (wenige Bits/Bin) für den Fast–Datenpuffer reserviert.

- Gesendet werden dann neue Tabellen für Upstream und Downstream, in denen die Bins nicht mehr nach dem Index geordnet sind, sondern entsprechend den Bits/Bin–Verhältnissen. Anhand dieser neuen Tabelle ist es für die $\rm ATU–C$ bzw. $\rm ATU–R$ möglich, die Bit–Extraktion erfolgreich durchzuführen.

Einfügen von Guard–Intervall und zyklischem Präfix

Im Kapitel Realisierung von OFDM–Systemen des Buches "Modulationsverfahren" wurde bereits gezeigt, dass durch die Einfügung eines Schutzabstandes – man bezeichnet diesen auch als Guard–Intervall oder Guard–Lücke – die Bitfehlerrate bei Vorhandensein von linearen Kanalverzerrungen entscheidend verbessert werden kann.

Wir gehen davon aus, dass sich die Kabelimpulsantwort $h_{\rm K}(t)$ über die Zeitdauer $T_{\rm K}$ erstreckt. Ideal wäre $h_{\rm K}(t) = δ(t)$ und dementsprechend eine unendlich kurze Ausdehnung: $T_{\rm K} = 0$. Bei verzerrendem Kanal $(T_{\rm K} > 0 )$ gilt:

- Durch Einfügung eines Guard–Intervalls der Dauer $T_{\rm G}$ lassen sich Intersymbolinterferenzen zwischen den einzelnen DSL–Rahmen vermeiden, solange $T_{\rm G}$ ≥ $T_{\rm K}$ gilt. Diese Maßnahme führt allerdings zu einem Ratenverlust um den Faktor $T/(T + T_{\rm G})$ mit der Symboldauer $T = {1}/{f_0}$.

- Damit gibt es aber immer noch Inter–Carrier–Interferenzen zwischen den einzelnen Subträgern innerhalb des gleichen Rahmens, das heißt, die DMT–Einzelspektren sind nicht mehr $\rm si$–förmig und es kommt zu einer De–Orthogonalisierung.

- Durch ein zyklisches Präfix lässt sich auch dieser störende Effekt vermeiden. Dabei erweitert man den Sendevektor $\mathbf{s}$ nach vorne um die letzten $L$ Abtastwerte des IDFT–Ausgangs, wobei der Minimalwert für $L$ durch die Dauer $T_{\rm K}$ der Kabelimpulsantwort vorgegeben ist.

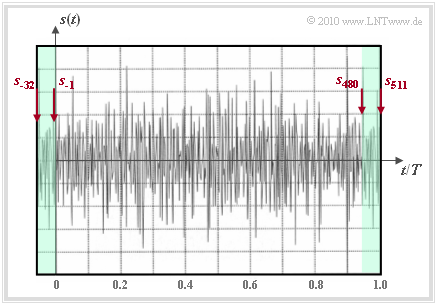

$\text{Beispiel 6:}$ Die Grafik zeigt diese Maßnahme beim DSL/DMT–Verfahren, für das der Parameter $L = 32$ festgelegt wurde.

- Die Abtastwerte $s_{480}$ , ... , $s_{511}$ werden als Präfix $(s_{-32}$ , ... , $s_{-1})$ zum IDFT–Ausgangsvektor $(s_0$ , ... , $s_{511})$ hinzugefügt.

- Das Sendesignal $s(t)$ hat nun statt der Symboldauer $T ≈ 232 \ {\rm µ s}$ die resultierende Dauer $T + T_{\rm G} = 1.0625 \cdot T ≈ 246 \ {\rm µ s}$. Dadurch wird die Rate um den Faktor $0.94$ verringert.

- Bei der empfangsseitigen Auswertung beschränkt man sich auf den Zeitbereich von $0$ bis $T$. In diesem Zeitintervall ist der störende Einfluss der Impulsantwort bereits abgeklungen und die Subkanäle sind – ebenso wie bei idealem Kanal – zueinander orthogonal.

- Die Abtastwerte $s_{-32}$ , ... , $s_{-1}$ werden am Empfänger verworfen – eine recht einfache Realisierung der Signalentzerrung.

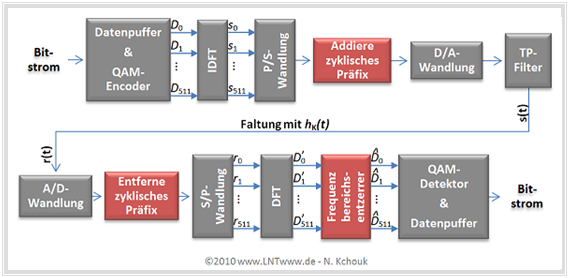

Die letzte Grafik dieses Kapitels zeigt das gesamte DMT–Übertragungssystem, allerdings ohne die vorne beschriebenen Fehlerschutzmaßnahmen. Man erkennt:

- Im Block „Addiere zyklisches Präfix” werden die Abtastwerte $s_{480}$, ... , $s_{511}$ als $s_{-32}$, ... , $s_{-1}$ hinzugefügt. Das Sendesignal $s(t)$ hat somit den im $\text{Beispiel 6}$ gezeigten Verlauf.

- Das Empfangsignal $r(t)$ ergibt sich aus der Faltung von $s(t)$ mit $h_{\rm K}(t)$. Nach A/D–Wandlung und Entfernen des zyklischen Präfix erhält man die Eingangswerte $r_0$, ... , $ r_{511}$ für die DFT.

- Die (komplexen) Ausgangswerte $D_k\hspace{0.01cm}'$ der DFT hängen nur vom jeweiligen (komplexen) Datenwert $D_k$ ab. Unabhängig von anderen Daten $D_κ (κ ≠ k)$ gilt mit dem Rauschwert $n_k\hspace{0.01cm}'$:

- $${D}_k\hspace{0.01cm}' = \alpha_k \cdot {D}_k + {n}_k\hspace{0.01cm}', \hspace{0.2cm}\alpha_k = H_{\rm K}( f = f_k) \hspace{0.05cm}. $$

- Jeder Träger $D_k$ wird durch einen eigenen (komplexen) Faktor $α_k$, der nur vom Kanal abhängt, in seiner Amplitude und Phase verändert. Der Frequenzbereichsentzerrer hat nur die Aufgabe, den Koeffizienten $D_k\hspace{0.01cm}'$ mit dem inversen Wert ${1}/{α_k}$ zu multiplizieren. Man erhält schließlich:

- $$ \hat{D}_k = {D}_k + {n}_k \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

$\text{Fazit:}$

- Diese einfache Realisierungsmöglichkeit der vollständigen Entzerrung des stark verzerrenden Kabelfrequenzgangs war eines der entscheidenden Kriterien, dass sich bei $\rm xDSL$ das $\rm DMT$–Verfahren gegenüber $\rm QAM$ und $\rm CAP$ durchgesetzt hat.

- Meist findet direkt nach der A/D–Wandlung zusätzlich noch eine Vorentzerrung im Zeitbereich statt, um auch die Intersymbolinterferenzen zwischen benachbarten Rahmen zu vermeiden.

Aufgaben zum Kapitel

Aufgabe 2.5: DSL–Fehlersicherungsmaßnahmen

Aufgabe 2.5Z: Reichweite und Bitrate bei ADSL

Aufgabe 2.6: Zyklisches Präfix

Quellenverzeichnis

- ↑ Pollakowski, M.; Wellhausen, H.W.: Properties of symmetrical local access cables in the frequency range up to 30 MHz. Communication from the Research and Technology Center of Deutsche Telekom AG, Darmstadt, Verlag für Wissenschaft und Leben Georg Heidecker, 1995.