Difference between revisions of "Linear and Time Invariant Systems/Properties of Coaxial Cables"

| (16 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

==Complex propagation function of coaxial cables== | ==Complex propagation function of coaxial cables== | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | Coaxial cables consist of an inner conductor and – separated by a dielectric – an outer conductor. Two different types of cable have been standardized, with the diameters of the inner and outer conductors mentioned for identification purposes: | + | Coaxial cables consist of an inner conductor and – separated by a dielectric – an outer conductor. Two different types of cable have been standardized, with the diameters of the inner and outer conductors mentioned for identification purposes: |

| − | *the | + | *the »standard coaxial cable« whose inner conductor has a diameter of $\text{2.6 mm}$ and whose outer diameter is $\text{9.5 mm}$, |

| − | |||

| + | *the »small coaxial cable« with diameters $\text{1.2 mm}$ and $\text{4.4 mm}$. | ||

| − | The cable frequency response $H_{\rm K}(f)$ results from the cable length $l$ and the complex propagation function (per unit length) | + | |

| + | The cable frequency response $H_{\rm K}(f)$ results from the cable length $l$ and the complex propagation function $($per unit length$)$ | ||

:$$\gamma(f) = \alpha_0 + \alpha_1 \cdot f + \alpha_2 \cdot \sqrt {f}+ {\rm j}\cdot (\beta_1 \cdot f + \beta_2 \cdot \sqrt {f})\hspace{0.05cm}\hspace{0.3cm} | :$$\gamma(f) = \alpha_0 + \alpha_1 \cdot f + \alpha_2 \cdot \sqrt {f}+ {\rm j}\cdot (\beta_1 \cdot f + \beta_2 \cdot \sqrt {f})\hspace{0.05cm}\hspace{0.3cm} | ||

\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}H_{\rm K}(f) = {\rm e}^{-\gamma(f)\hspace{0.05cm} \cdot \hspace{0.05cm} l} \hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}|H_{\rm K}(f)| = {\rm e}^{-\alpha(f)\hspace{0.05cm} \cdot \hspace{0.05cm} l}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | \Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}H_{\rm K}(f) = {\rm e}^{-\gamma(f)\hspace{0.05cm} \cdot \hspace{0.05cm} l} \hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}|H_{\rm K}(f)| = {\rm e}^{-\alpha(f)\hspace{0.05cm} \cdot \hspace{0.05cm} l}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| − | The cable specific constants for the '''standard coaxial cable''' $\text{(2.6/9.5 mm)}$ are: | + | The cable specific constants for the »'''standard coaxial cable'''« $\text{(2.6/9.5 mm)}$ are: |

:$$\begin{align*}\alpha_0 & = 0.00162\, \frac{ {\rm Np} }{ {\rm km} }\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} \alpha_1 = 0.000435\, \frac{ {\rm Np} }{ {\rm km \cdot MHz} }\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} \alpha_2 = 0.2722\, \frac{ {\rm Np} }{ {\rm km \cdot \sqrt{MHz} } }\hspace{0.05cm}, \\ \beta_1 & = 21.78\, \frac{ {\rm rad} }{ {\rm km \cdot MHz} }\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} \beta_2 = 0.2722\, \frac{ {\rm rad} }{ {\rm km \cdot \sqrt{MHz} } } \hspace{0.05cm}.\end{align*}$$ | :$$\begin{align*}\alpha_0 & = 0.00162\, \frac{ {\rm Np} }{ {\rm km} }\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} \alpha_1 = 0.000435\, \frac{ {\rm Np} }{ {\rm km \cdot MHz} }\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} \alpha_2 = 0.2722\, \frac{ {\rm Np} }{ {\rm km \cdot \sqrt{MHz} } }\hspace{0.05cm}, \\ \beta_1 & = 21.78\, \frac{ {\rm rad} }{ {\rm km \cdot MHz} }\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} \beta_2 = 0.2722\, \frac{ {\rm rad} }{ {\rm km \cdot \sqrt{MHz} } } \hspace{0.05cm}.\end{align*}$$ | ||

| − | Accordingly, the kilometric attenuation and phase constants for the '''small coaxial cable''' $\text{(1.2/4.4 mm)}$: | + | Accordingly, the kilometric attenuation and phase constants for the »'''small coaxial cable'''« $\text{(1.2/4.4 mm)}$: |

:$$\begin{align*}\alpha_0 & = 0.00783\, \frac{ {\rm Np} }{ {\rm km} }\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} | :$$\begin{align*}\alpha_0 & = 0.00783\, \frac{ {\rm Np} }{ {\rm km} }\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} | ||

\alpha_1 = 0.000443\, \frac{ {\rm Np} }{ {\rm km \cdot MHz} }\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} \alpha_2 = 0.5984\, \frac{ {\rm Np} }{ {\rm km \cdot \sqrt{MHz} } }\hspace{0.05cm}, \\ \beta_1 & = 22.18\, \frac{ {\rm rad} }{ {\rm km \cdot MHz} }\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} \beta_2 = 0.5984\, \frac{ {\rm rad} }{ {\rm km \cdot \sqrt{MHz} } } \hspace{0.05cm}.\end{align*}$$ | \alpha_1 = 0.000443\, \frac{ {\rm Np} }{ {\rm km \cdot MHz} }\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} \alpha_2 = 0.5984\, \frac{ {\rm Np} }{ {\rm km \cdot \sqrt{MHz} } }\hspace{0.05cm}, \\ \beta_1 & = 22.18\, \frac{ {\rm rad} }{ {\rm km \cdot MHz} }\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} \beta_2 = 0.5984\, \frac{ {\rm rad} }{ {\rm km \cdot \sqrt{MHz} } } \hspace{0.05cm}.\end{align*}$$ | ||

| Line 25: | Line 26: | ||

These values can be calculated from the geometric dimensions of the cables and have been confirmed by measurements at the Fernmeldetechnisches Zentralamt in Darmstadt - see [Wel77]<ref>Wellhausen, H. W.: Dämpfung, Phase und Laufzeiten bei Weitverkehrs–Koaxialpaaren. Frequenz 31, S. 23-28, 1977.</ref>. They apply to a temperature of $20^\circ\ \text{C (293 K)}$ and frequencies greater than $\text{200 kHz}$. | These values can be calculated from the geometric dimensions of the cables and have been confirmed by measurements at the Fernmeldetechnisches Zentralamt in Darmstadt - see [Wel77]<ref>Wellhausen, H. W.: Dämpfung, Phase und Laufzeiten bei Weitverkehrs–Koaxialpaaren. Frequenz 31, S. 23-28, 1977.</ref>. They apply to a temperature of $20^\circ\ \text{C (293 K)}$ and frequencies greater than $\text{200 kHz}$. | ||

| − | There is the following connection to the [[Linear_and_Time_Invariant_Systems/Some_Results_from_Line_Transmission_Theory#Equivalent_circuit_diagram_of_a_short_transmission_line_section|primary line parameters]]: | + | There is the following connection to the [[Linear_and_Time_Invariant_Systems/Some_Results_from_Line_Transmission_Theory#Equivalent_circuit_diagram_of_a_short_transmission_line_section|»primary line parameters«]]: |

| − | + | #The ohmic losses originating from the frequency-independent component $R\hspace{0.05cm}'$ are modeled by the parameter $α_0$ and cause a $($for coaxial cables small$)$ frequency-independent attenuation. | |

| − | + | #The component $α_1 · f$ of the »attenuation function (per unit length)« is due to the derivation losses $(G\hspace{0.08cm}’)$ and the frequency-proportional term $β_1 · f$ causes only delay but no distortion. | |

| − | + | #The components $α_2$ and $β_2$ are due to the [[Digital_Signal_Transmission/Causes_and_Effects_of_Intersymbol_Interference#Frequency_response_of_a_coaxial_cable|»'''skin effect'''«]], which causes the current density inside the conductor to be lower than at the surface in the case of higher-frequency alternating current. As a result, the »serial resistance (per unit length)« $R\hspace{0.05cm}’$ of an electric line increases with the square root of the frequency. | |

==Characteristic cable attenuation== | ==Characteristic cable attenuation== | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

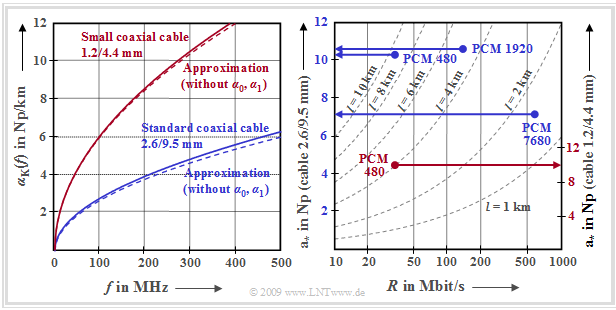

The graph shows the frequency-dependent attenuation curve for the normal coaxial cable and the small coaxial cable. Shown on the left is the cable attenuation per unit length of the two coaxial cable types in the frequency range up to $\text{500 MHz}$: | The graph shows the frequency-dependent attenuation curve for the normal coaxial cable and the small coaxial cable. Shown on the left is the cable attenuation per unit length of the two coaxial cable types in the frequency range up to $\text{500 MHz}$: | ||

| − | [[File:EN_LZI_4_2_S2_neu.png |right|frame| Attenuation function and characteristic attenuation of coaxial cables | + | [[File:EN_LZI_4_2_S2_neu.png |right|frame| Attenuation function and characteristic attenuation of coaxial cables]] |

:$${\alpha}_{\rm K}(f) \hspace{-0.05cm} = \alpha_0 \hspace{-0.05cm}+ \hspace{-0.05cm} \alpha_1 \cdot f \hspace{-0.05cm}+ \hspace{-0.05cm} \alpha_2 \hspace{-0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{-0.05cm}\sqrt {f} \hspace{0.01cm} \hspace{0.01cm}.$$ | :$${\alpha}_{\rm K}(f) \hspace{-0.05cm} = \alpha_0 \hspace{-0.05cm}+ \hspace{-0.05cm} \alpha_1 \cdot f \hspace{-0.05cm}+ \hspace{-0.05cm} \alpha_2 \hspace{-0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{-0.05cm}\sqrt {f} \hspace{0.01cm} \hspace{0.01cm}.$$ | ||

:$$\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}{\rm a}_{\rm K}(f) =\alpha_{\rm K}(f) \cdot l $$ | :$$\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}{\rm a}_{\rm K}(f) =\alpha_{\rm K}(f) \cdot l $$ | ||

| Line 39: | Line 40: | ||

'''Notes on the representation chosen here''' | '''Notes on the representation chosen here''' | ||

| − | + | #To make the difference between the attenuation function per unit length »alpha« and the function »a« $($after multiplication by length$)$ more recognizable, the attenuation function is written here as ${\rm a}_{\rm K}(f)$ and not $($''italics''$)$ as ${a}_{\rm K}(f)$. | |

| − | + | #The ordinate labeling is given here in »Np/km«. Often it is also done in »dB/km«, with the following conversion: | |

| − | :$$\ln(10)/20 = 0.11513\text{...} \hspace{0.3cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} 1 \ \rm dB = 0.11513\text{... Np.} $$ | + | ::$$\ln(10)/20 = 0.11513\text{...} \hspace{0.3cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} 1 \ \rm dB = 0.11513\text{... Np.} $$ |

'''Interpretation of the left graph''' | '''Interpretation of the left graph''' | ||

| − | *It can be seen from the curves shown that the error is still tolerable when neglecting the frequency-independent component $α_0$ and the frequency-proportional term $(α_1\cdot f)$. | + | *It can be seen from the curves shown that the error is still tolerable when neglecting the frequency-independent component $α_0$ and the frequency-proportional term $(α_1\cdot f)$. |

| − | * | + | |

| + | *Sometimes, we assume the »'''simplified attenuation function'''«: | ||

:$${\rm a}_{\rm K}(f) = \alpha_2 \cdot \sqrt {f} \cdot l = {\rm a}_{\rm \star}\cdot \sqrt | :$${\rm a}_{\rm K}(f) = \alpha_2 \cdot \sqrt {f} \cdot l = {\rm a}_{\rm \star}\cdot \sqrt | ||

{ {2f}/{R}} \hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}|H_{\rm K}(f)| = {\rm e}^{- {\rm a}_{\rm K}(f)}\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} {\rm a}_{\rm K}(f)\hspace{0.15cm}{\rm in }\hspace{0.15cm}{\rm Np}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | { {2f}/{R}} \hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}|H_{\rm K}(f)| = {\rm e}^{- {\rm a}_{\rm K}(f)}\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} {\rm a}_{\rm K}(f)\hspace{0.15cm}{\rm in }\hspace{0.15cm}{\rm Np}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| Line 52: | Line 54: | ||

{{BlaueBox|TEXT= | {{BlaueBox|TEXT= | ||

$\text{Definition:}$ | $\text{Definition:}$ | ||

| − | + | We denote as »'''characteristic cable attenuation'''« $\rm a_∗$ | |

| + | *the attenuation of a coaxial cable at half the bit rate | ||

| + | |||

| + | *due to the $α_2$ term alone ⇒ »skin effect«, thus neglecting the $α_0$ and the $α_1$ term: | ||

:$${\rm a}_{\rm \star} = {\rm a}_{\rm K}(f = {R}/{2}) = \alpha_2 \cdot \sqrt {{R}/{2}} \cdot l\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | :$${\rm a}_{\rm \star} = {\rm a}_{\rm K}(f = {R}/{2}) = \alpha_2 \cdot \sqrt {{R}/{2}} \cdot l\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

This value is particularly suitable for comparing different conducted transmission systems with different | This value is particularly suitable for comparing different conducted transmission systems with different | ||

| − | + | #coaxial cable types $($normal or small coaxial cable$)$, each identified by the parameter $\alpha_2$, | |

| − | + | #bit rates $(R)$, and | |

| − | + | #cable lengths $(l)$.}} | |

'''Interpretation of the right graph''' | '''Interpretation of the right graph''' | ||

| − | The right diagram shows the characteristic cable attenuation $\rm a_∗$ in | + | The right–hand diagram above shows the characteristic cable attenuation $\rm a_∗$ in »Neper« $\rm (Np)$ as a function of the bit rate $R$ and the cable length $l$ for |

| − | * | + | *the normal coaxial cable $\text{(2.6/9.5 mm)}$ ⇒ left ordinate labeling, and |

| − | *for the small coaxial cable ( | + | |

| + | *for the small coaxial cable $\text{(1.2/4.4 mm)}$ ⇒ right ordinate labeling. | ||

| − | This diagram shows the PCM systems of hierarchy levels $3$ to $5$ proposed by the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ITU-T | + | This diagram shows the PCM systems of hierarchy levels $3$ to $5$ proposed by the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ITU-T $\text{ITU-T}$] $($»ITU Telecommunication Standardization Sector«$)$ in the 1970s. One recognizes: |

| − | + | #For all these systems for PCM speech transmission, the characteristic cable attenuation assumes values between $7 \ \rm Np \ \ (≈ 61 \ dB)$ and $10.6 \ \rm Np \ \ (≈ 92 \ dB)$ . | |

| − | + | #The system $\text{PCM 480}$ – designed for 480 simultaneous telephone calls - with bit rate $R ≈ 35 \ \rm Mbit/s$ was specified for both the normal coaxial cable $($with $l = 9.3 \ \rm km)$ and the small coaxial cable $($with $l = 4 \ \rm km)$. The $\rm a_∗$–values $10.4\ \rm Np$ resp. $9.9\ \rm Np$ are in the same order of magnitude. | |

| − | + | #The system $\text{PCM 1920}$ of the fourth hierarchy level $($specified for the normal coaxial cable$)$ with $R ≈ 140 \ \rm Mbit/s$ and $l = 4.65 \ \rm km$ is parameterized by $\rm a_∗ = 10.6 \ \rm Np$ or $10.6 \ {\rm Np}· 8.688 \ \rm dB/Np ≈ 92\ \rm dB$ . | |

| − | + | #Although the system $\text{PCM 7680}$ has a four times greater bit rate $R ≈ 560 \ \rm Mbit/s$ , the characteristic cable attenuation of $\rm a_∗ ≈ 61 \ dB$ is due to the better medium »normal coaxial cable« and the shorter cable sections $(l = 1. 55 \ \rm km)$ by a factor of $3$ significantly lower . | |

| − | + | #These numerical values also show that for coaxial cable systems, the cable length $l$ is more critical than the bit rate $R$. If one wants to double the cable length, one has to reduce the bit rate by a factor $4$. | |

| − | You can view the topic described here with the interactive HTLM 5/ | + | You can view the topic described here with the interactive HTLM 5/JavaScript applet [[Applets:Attenuation_of_Copper_Cables|»Attenuation of Copper Cables«]] . |

==Impulse response of a coaxial cable== | ==Impulse response of a coaxial cable== | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | To calculate the impulse response, the first two | + | To calculate the impulse response, the first two of the in total five components of the complex propagation function $($per unit length$)$ can be neglected $($the reasoning can be found in the previous section$)$. So we start from the following equation: |

:$$\gamma(f) = \alpha_0 + \alpha_1 \cdot f + {\rm j} \cdot \beta_1 \cdot f +\alpha_2 \cdot \sqrt {f}+ {\rm j}\cdot \beta_2 \cdot \sqrt {f} \approx {\rm j} \cdot \beta_1 \cdot f +\alpha_2 \cdot \sqrt {f}+ {\rm j}\cdot \beta_2 \cdot \sqrt {f} \hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | :$$\gamma(f) = \alpha_0 + \alpha_1 \cdot f + {\rm j} \cdot \beta_1 \cdot f +\alpha_2 \cdot \sqrt {f}+ {\rm j}\cdot \beta_2 \cdot \sqrt {f} \approx {\rm j} \cdot \beta_1 \cdot f +\alpha_2 \cdot \sqrt {f}+ {\rm j}\cdot \beta_2 \cdot \sqrt {f} \hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

Considering | Considering | ||

| − | + | #the cable length $l$, | |

| − | + | #the characteristic cable attenuation $\rm a_∗$, and | |

| − | + | #that $α_2$ $($in »Np«$)$ and $β_2$ (in »rad«$)$ are numerically equal, | |

| − | thus applies to the frequency response of the coaxial cable: | + | thus applies to the »frequency response of the coaxial cable«: |

:$$H_{\rm K}(f) = {\rm e}^{-{\rm j}\hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm} b_1 f} \cdot {\rm e}^{-{\rm a}_{\rm \star}\hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm} \sqrt{2f/R} }\cdot {\rm e}^{-{\rm j}\hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm}{\rm a}_{\rm \star}\hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.02cm} \sqrt{2f/R}}= {\rm e}^{-{\rm j}\hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm} b_1 f} \cdot {\rm e}^{-2{\rm a}_{\rm \star}\hspace{0.03cm}\cdot \hspace{0.03cm} \sqrt{ {\rm j}\hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm}f/R}} \hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | :$$H_{\rm K}(f) = {\rm e}^{-{\rm j}\hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm} b_1 f} \cdot {\rm e}^{-{\rm a}_{\rm \star}\hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm} \sqrt{2f/R} }\cdot {\rm e}^{-{\rm j}\hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm}{\rm a}_{\rm \star}\hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.02cm} \sqrt{2f/R}}= {\rm e}^{-{\rm j}\hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm} b_1 f} \cdot {\rm e}^{-2{\rm a}_{\rm \star}\hspace{0.03cm}\cdot \hspace{0.03cm} \sqrt{ {\rm j}\hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm}f/R}} \hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

The following abbreviations are used here: | The following abbreviations are used here: | ||

:$$b_1\hspace{0.1cm}{(\rm in }\hspace{0.15cm}{\rm rad)}= \beta_1 \cdot l \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.8cm} {\rm a}_{\rm \star}\hspace{0.1cm}{(\rm in }\hspace{0.15cm}{\rm Np)}= \alpha_2 \cdot \sqrt {R/2} \cdot l \hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | :$$b_1\hspace{0.1cm}{(\rm in }\hspace{0.15cm}{\rm rad)}= \beta_1 \cdot l \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.8cm} {\rm a}_{\rm \star}\hspace{0.1cm}{(\rm in }\hspace{0.15cm}{\rm Np)}= \alpha_2 \cdot \sqrt {R/2} \cdot l \hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| − | The time domain | + | The time domain representation is obtained by applying the [[Signal_Representation/Fourier_Transform_and_its_Inverse#The_second_Fourier_integral|»inverse Fourier transform«]] and the [[Signal_Representation/The_Convolution_Theorem_and_Operation|»convolution theorem«]]: |

:$$h_{\rm K}(t) = \mathcal{F}^{-1} \left \{ {\rm e}^{-{\rm j}\hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm} b_1 | :$$h_{\rm K}(t) = \mathcal{F}^{-1} \left \{ {\rm e}^{-{\rm j}\hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm} b_1 | ||

f}\right \} \star\mathcal{F}^{-1} \left \{ {\rm e}^{-2{\rm a}_{\rm \star}\hspace{0.03cm}\cdot \hspace{0.03cm} \sqrt{ {\rm j}\hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm}f/R} }\right \} \hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | f}\right \} \star\mathcal{F}^{-1} \left \{ {\rm e}^{-2{\rm a}_{\rm \star}\hspace{0.03cm}\cdot \hspace{0.03cm} \sqrt{ {\rm j}\hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm}f/R} }\right \} \hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| − | + | It must be taken into account here: | |

| − | *The first term yields the Dirac delta function $δ(t - τ_{\rm P})$ shifted by the phase delay $τ_{\rm P} = b_1/2π$ . | + | *The first term yields the Dirac delta function $δ(t - τ_{\rm P})$ shifted by the phase delay $τ_{\rm P} = b_1/2π$ . |

| + | |||

*The second term can be given analytically closed. We write $h_{\rm K}(t + τ_P)$, so that the phase delay $τ_{\rm P}$ need not be considered further. | *The second term can be given analytically closed. We write $h_{\rm K}(t + τ_P)$, so that the phase delay $τ_{\rm P}$ need not be considered further. | ||

:$$h_{\rm K}(t + \tau_{\rm P}) = \frac {{\rm a}_{\rm \star}}{\pi \cdot \sqrt{2 \cdot R \cdot t^3}}\cdot {\rm exp} \left [ -\frac {{\rm a}_{\rm \star}^2}{ {2\pi \cdot R\cdot t}} \right ]\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}{\rm a}_{\rm \star}\hspace{0.15cm}{\rm in\hspace{0.15cm} Np}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | :$$h_{\rm K}(t + \tau_{\rm P}) = \frac {{\rm a}_{\rm \star}}{\pi \cdot \sqrt{2 \cdot R \cdot t^3}}\cdot {\rm exp} \left [ -\frac {{\rm a}_{\rm \star}^2}{ {2\pi \cdot R\cdot t}} \right ]\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}{\rm a}_{\rm \star}\hspace{0.15cm}{\rm in\hspace{0.15cm} Np}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| − | *Since the bit rate $R$ also has already been considered in the | + | *Since the bit rate $R$ also has already been considered in the $\rm a_∗$ definition; this equation can be easily represented with the normalized time $t\hspace{0.05cm}' = t/T$ : |

:$$h_{\rm K}(t\hspace{0.05cm}' + \tau_{\rm P}\hspace{0.05cm} ') = \frac {1}{T} \cdot \frac {{\rm a}_{\rm \star}}{\pi \cdot \sqrt{2 \cdot t\hspace{0.05cm}'\hspace{0.05cm}^3}}\cdot {\rm exp} \left [ -\frac {{\rm a}_{\rm \star}^2}{ {2\pi \cdot t\hspace{0.05cm}'}} \right ]\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}{\rm a}_{\rm \star}\hspace{0.15cm}{\rm in\hspace{0.15cm} Np}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | :$$h_{\rm K}(t\hspace{0.05cm}' + \tau_{\rm P}\hspace{0.05cm} ') = \frac {1}{T} \cdot \frac {{\rm a}_{\rm \star}}{\pi \cdot \sqrt{2 \cdot t\hspace{0.05cm}'\hspace{0.05cm}^3}}\cdot {\rm exp} \left [ -\frac {{\rm a}_{\rm \star}^2}{ {2\pi \cdot t\hspace{0.05cm}'}} \right ]\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}{\rm a}_{\rm \star}\hspace{0.15cm}{\rm in\hspace{0.15cm} Np}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| − | :Here $T = 1/R$ denotes the symbol duration of a binary system and it holds $τ_{\rm P} \hspace{0.05cm}' = τ_{\rm P}/T$. | + | :Here $T = 1/R$ denotes »the symbol duration of a binary system« and it holds $τ_{\rm P} \hspace{0.05cm}' = τ_{\rm P}/T$. |

{{GraueBox|TEXT= | {{GraueBox|TEXT= | ||

$\text{Example 1:}$ | $\text{Example 1:}$ | ||

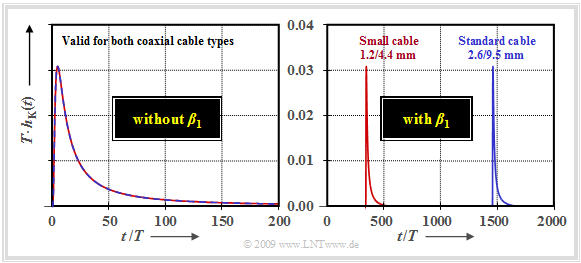

| − | The results of this | + | The results of this section are illustrated by the following graph as an example. |

| − | [[File:EN_LZI_4_2_S3_neu.png|right|frame| Impulse response of a coaxial cable with $\rm a_∗ = 60 \ dB$ | + | [[File:EN_LZI_4_2_S3_neu.png|right|frame| Impulse response of a coaxial cable with $\rm a_∗ = 60 \ dB$]] |

| − | + | #The normalized impulse response $T · h_{\rm K}(t)$ of a coaxial cable with $\rm a_∗ = 60 \ dB \ \ (6.9\ Np)$ is shown. | |

| − | + | #The attenuation coefficients $α_0$ and $α_1$ can thus be neglected, as shown in the last section. | |

| − | + | #For the left graph, the parameter $β_1 = 0$ was also set. | |

| − | Because of the parameterization by the coefficient $a_∗$ | + | Because of the parameterization by the coefficient $\rm a_∗$, and the time normalization to the symbol duration $T$ the left curve is equally valid |

| − | *normal coaxial cable $\text{2.6/9.5 mm}$, bit rate $R = 140 \ \rm Mbit/s$, cable length $l = 3 \ \rm km$ ⇒ | + | #for systems with small or normal coaxial cable, |

| − | *small coaxial cable $\text{1.2/4.4 | + | #different lengths, |

| + | #different bit rates. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | For example for | ||

| + | *normal coaxial cable $\text{2.6/9.5 mm}$, bit rate $R = 140 \ \rm Mbit/s$, cable length $l = 3 \ \rm km$ ⇒ $\text{system A}$, | ||

| + | *small coaxial cable $\text{1.2/4.4 mm}$, bit rate $R = 35 \ \rm Mbit/s$, <br>cable length $l = 2.8 \ \rm km$ ⇒ $\text{system B}$. | ||

<br clear=all> | <br clear=all> | ||

| − | It can be seen that even at this moderate cable attenuation $\rm a_∗ = 60 \ \rm dB$ the impulse response already extends over more than $200$ symbol durations due to the skin effect $(α_2 = β_2 ≠ 0)$. Since the integral over $h_{\rm K}(t)$ is equal to $H_{\rm K}(f = 0) = 1$, the maximum value becomes very small: | + | It can be seen in the left–hand diagram that even at this moderate cable attenuation $\rm a_∗ = 60 \ \rm dB$ the impulse response already extends over more than $200$ symbol durations due to the skin effect $(α_2 = β_2 ≠ 0)$. Since the integral over $h_{\rm K}(t)$ is equal to $H_{\rm K}(f = 0) = 1$, the maximum value becomes very small: |

:$${\rm Max}\big [h_{\rm K}(t)\big ] \approx 0.03.$$ | :$${\rm Max}\big [h_{\rm K}(t)\big ] \approx 0.03.$$ | ||

| − | In the diagram on the right, the effects of the phase parameter $β_1$ can be seen. Note the different time scales of the left and the right diagram: | + | In the diagram on the right, the effects of the phase parameter $β_1$ can be seen. Note the different time scales of the left and the right diagram: |

| − | *For | + | *For $\text{system A}$ $(β_1 = 21.78 \ \rm rad/(km · MHz)$, $T = 7.14\ \rm ns)$ $β_1$ leads to a phase delay of |

:$$\tau_{\rm A}= \frac {\beta_1 \cdot l}{2\pi} =\frac {21.78\, { {\rm rad} }/{ {(\rm km \cdot MHz)} }\cdot 3\,{\rm km} }{2\pi} = 10.4\,{\rm \mu s}\hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}\tau_{\rm A}\hspace{0.05cm}' = {\tau_{\rm A} }/{T} \approx 1457\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | :$$\tau_{\rm A}= \frac {\beta_1 \cdot l}{2\pi} =\frac {21.78\, { {\rm rad} }/{ {(\rm km \cdot MHz)} }\cdot 3\,{\rm km} }{2\pi} = 10.4\,{\rm \mu s}\hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}\tau_{\rm A}\hspace{0.05cm}' = {\tau_{\rm A} }/{T} \approx 1457\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| − | *On the other hand, the following can be obtained for | + | *On the other hand, the following can be obtained for $\text{system B}$ $(β_1 = 22.18 \ \rm rad/(km · MHz)$, $T = 30 \ \rm ns)$: |

:$$\tau_{\rm B}= \frac {\beta_1 \cdot l}{2\pi} =\frac {22.18\, { {\rm rad} }/{ {(\rm km \cdot MHz)} }\cdot 2.8\,{\rm km} }{2\pi} = 9.9\,{\rm µ s}\hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}\tau_{\rm B}\hspace{0.05cm}' ={\tau_{\rm B} }/{T} \approx 330\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | :$$\tau_{\rm B}= \frac {\beta_1 \cdot l}{2\pi} =\frac {22.18\, { {\rm rad} }/{ {(\rm km \cdot MHz)} }\cdot 2.8\,{\rm km} }{2\pi} = 9.9\,{\rm µ s}\hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}\tau_{\rm B}\hspace{0.05cm}' ={\tau_{\rm B} }/{T} \approx 330\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| Line 131: | Line 144: | ||

{{BlaueBox|TEXT= | {{BlaueBox|TEXT= | ||

| − | $\text{Conclusion:}$ When simulating and optimizing | + | $\text{Conclusion:}$ When simulating and optimizing transmission systems, <br>'''one usually omits the linear phase term''' $b_1 = β_1 · f$, since this results exclusively in a $($often not disturbing$)$ phase delay, '''but no signal distortions'''.}} |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ==Basic receiver pulse== | |

| − | |||

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | With the basic transmission pulse $g_s(t)$ ⇒ | + | With the »basic transmission pulse« $g_s(t)$ ⇒ »basic pulse of the transmitted signal« $s(t)$ and the »impulse response $h_{\rm K}(t)$ of the channel, the result for the »basic receiver pulse« $g_r(t)$ ⇒ »basic pulse of the received signal« $r(t)$ is: |

:$$g_r(t) = g_s(t) \star h_{\rm K}(t)\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | :$$g_r(t) = g_s(t) \star h_{\rm K}(t)\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| − | If a non-return-to-zero (NRZ) rectangular pulse $g_s(t)$ with amplitude $s_0$ and duration $Δt_s = T$ is used at the transmitter, the following results for the basic pulse at the receiver input: | + | If a non-return-to-zero $\rm (NRZ)$ rectangular pulse $g_s(t)$ with amplitude $s_0$ and duration $Δt_s = T$ is used at the transmitter, the following results for the basic pulse at the receiver input: |

:$$g_r(t) = 2 s_0 \cdot \left [ {\rm Q} \left (\frac {{\rm a}_{\rm \star}/\sqrt {\pi}}{ \sqrt{ (t/T - 0.5)}}\right ) - | :$$g_r(t) = 2 s_0 \cdot \left [ {\rm Q} \left (\frac {{\rm a}_{\rm \star}/\sqrt {\pi}}{ \sqrt{ (t/T - 0.5)}}\right ) - | ||

{\rm Q} \left (\frac {{\rm a}_{\rm \star}/\sqrt {\pi}}{ \sqrt{ (t/T + 0.5)}}\right ) \right ]\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | {\rm Q} \left (\frac {{\rm a}_{\rm \star}/\sqrt {\pi}}{ \sqrt{ (t/T + 0.5)}}\right ) \right ]\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| − | Here $\rm a_∗$ denotes the characteristic cable attenuation (in Neper) and ${\rm Q}(x)$ the [[Theory_of_Stochastic_Signals/Gaussian_Distributed_Random_Variables# | + | Here $\rm a_∗$ denotes the »characteristic cable attenuation« $($in Neper$)$ and ${\rm Q}(x)$ the [[Theory_of_Stochastic_Signals/Gaussian_Distributed_Random_Variables#Exceedance_probability|»complementary Gaussian error function«]]. |

| − | |||

{{GraueBox|TEXT= | {{GraueBox|TEXT= | ||

$\text{Example 2:}$ | $\text{Example 2:}$ | ||

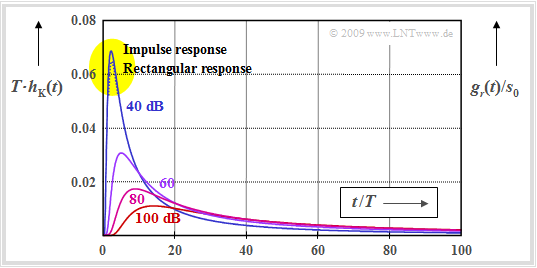

| − | The figure shows for the characteristic cable attenuations $\rm a_∗ = 40 \ \rm dB$, ... , $100 \ \rm dB$ (smaller $\rm a_∗$–values are not relevant for practice) | + | The figure shows for the characteristic cable attenuations $\rm a_∗ = 40 \ \rm dB$, ... , $100 \ \rm dB$ $($smaller $\rm a_∗$–values are not relevant for practice$)$ |

| − | *the normalized coaxial cable impulse response $T · h_{\rm K}(t)$ ⇒ solid curves, | + | *the normalized coaxial cable impulse response $T · h_{\rm K}(t)$ ⇒ solid curves, |

| − | *the basic | + | |

| + | *the basic receiver pulse $($»rectangular response«$)$ $g_r(t)$ normalized to the transmission amplitude $s_0$ ⇒ dotted line. | ||

| + | [[File:EN_LZI_4_2_S4.png|right|frame|Impulse response of the coaxial cable and basic receiver pulse]] | ||

One recognizes the following from this diagram: | One recognizes the following from this diagram: | ||

| − | + | #With $\rm a_∗ = 40 \ \rm dB$, the normalized basic receiver pulse $g_r(t)/s_0$ is at the peak slightly $($about a factor of $0.95)$ smaller than the normalized impulse response $T · h_{\rm K}(t)$. Here is a small difference between impulse response and basic receiver pulse . | |

| − | + | #In contrast, for $a_∗ ≥ 60 \ \rm dB$, the basic receiver pulse and the impulse response are indistinguishable within the drawing accuracy. | |

| − | + | #For a return-to-zero $\rm (RZ)$ pulse, the above equation for $g_r(t)$ would still need to be multiplied by the factor $Δt_s/T$. In this case $g_r(t)/s_0$ is smaller than $T · h_{\rm K}(t)$ by at least this factor. | |

| − | + | #The equation modified in this way is also a good approximation for other basic transmission pulses as long as $\rm a_∗≥ 60 \ \rm dB$ is sufficiently large. $Δt_s$ then indicates the [[Signal_Representation/Special_Cases_of_Pulses#Gaussian_pulse|»equivalent pulse duration«]] of $g_r(t)$.}} | |

| − | + | ==Special features of coaxial cable systems== | |

| + | <br> | ||

| + | [[File:EN_LZI_4_2_S5_v2.png |right|frame| Binary transmission system with coaxial cable]] | ||

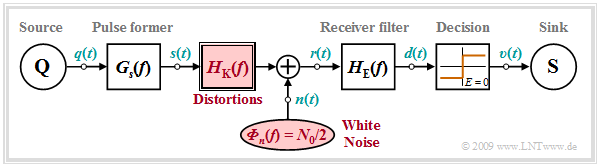

| + | Assuming binary transmission | ||

| + | |||

| + | *with non-return-to-zero $\rm (NRZ)$ rectangular pulses $($duration $T)$ | ||

| + | *and a coaxial transmission channel, | ||

| − | + | the following system model is obtained. In particular, it should be noted: | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | $(1)$ In a simulation, the phase delay time of the coaxial cable is conveniently left out of consideration. Then the basic receiver pulse $g_r(t)$ is approximated by $($with ${\rm a}_{\rm \star}$ in Neper$)$: | |

| + | :$$g_r(t) \approx s_0 \cdot T \cdot h_{\rm K}(t) = \frac {s_0 \cdot {\rm a}_{\rm \star}/\pi}{ \sqrt{2 \cdot(t/T)^3}}\cdot {\rm e}^{ -{{\rm a}_{\rm \star}^2}/( {2\pi \hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm}t/T}) } \hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| − | [[ | + | $(2)$ Because of the good shielding of coaxial cables against other impairments, the [[Aufgaben:Exercise_1.3Z:_Thermal_Noise|»thermal noise«]] is the dominant stochastic perturbation. In this case, the signal $n(t)$ is Gaussian and white. It can described by the $($two-sided$)$ noise power density $N_0/2$. |

| − | + | $(3)$ By far the largest noise component arises in the input stage of the receiver, so that it is expedient to add the noise signal $n(t)$ at the interface »cable ⇒ receiver«. This noise addition point is also useful because the frequency response $H_{\rm K}(f)$ decisively attenuates all noise accumulated along the cable. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | $(3)$ Then the received signal is with the amplitude coefficients $a_{\nu}$: | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

:$$r(t) = \sum_{\nu = - \infty}^{+ \infty}a_{\nu}\cdot g_r(t - \nu \cdot T)+ n(t) \hspace{0.05cm} .$$ | :$$r(t) = \sum_{\nu = - \infty}^{+ \infty}a_{\nu}\cdot g_r(t - \nu \cdot T)+ n(t) \hspace{0.05cm} .$$ | ||

| Line 188: | Line 205: | ||

| − | == | + | ==References== |

<references/> | <references/> | ||

{{Display}} | {{Display}} | ||

Latest revision as of 19:37, 24 November 2023

Contents

Complex propagation function of coaxial cables

Coaxial cables consist of an inner conductor and – separated by a dielectric – an outer conductor. Two different types of cable have been standardized, with the diameters of the inner and outer conductors mentioned for identification purposes:

- the »standard coaxial cable« whose inner conductor has a diameter of $\text{2.6 mm}$ and whose outer diameter is $\text{9.5 mm}$,

- the »small coaxial cable« with diameters $\text{1.2 mm}$ and $\text{4.4 mm}$.

The cable frequency response $H_{\rm K}(f)$ results from the cable length $l$ and the complex propagation function $($per unit length$)$

- $$\gamma(f) = \alpha_0 + \alpha_1 \cdot f + \alpha_2 \cdot \sqrt {f}+ {\rm j}\cdot (\beta_1 \cdot f + \beta_2 \cdot \sqrt {f})\hspace{0.05cm}\hspace{0.3cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}H_{\rm K}(f) = {\rm e}^{-\gamma(f)\hspace{0.05cm} \cdot \hspace{0.05cm} l} \hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}|H_{\rm K}(f)| = {\rm e}^{-\alpha(f)\hspace{0.05cm} \cdot \hspace{0.05cm} l}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

The cable specific constants for the »standard coaxial cable« $\text{(2.6/9.5 mm)}$ are:

- $$\begin{align*}\alpha_0 & = 0.00162\, \frac{ {\rm Np} }{ {\rm km} }\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} \alpha_1 = 0.000435\, \frac{ {\rm Np} }{ {\rm km \cdot MHz} }\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} \alpha_2 = 0.2722\, \frac{ {\rm Np} }{ {\rm km \cdot \sqrt{MHz} } }\hspace{0.05cm}, \\ \beta_1 & = 21.78\, \frac{ {\rm rad} }{ {\rm km \cdot MHz} }\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} \beta_2 = 0.2722\, \frac{ {\rm rad} }{ {\rm km \cdot \sqrt{MHz} } } \hspace{0.05cm}.\end{align*}$$

Accordingly, the kilometric attenuation and phase constants for the »small coaxial cable« $\text{(1.2/4.4 mm)}$:

- $$\begin{align*}\alpha_0 & = 0.00783\, \frac{ {\rm Np} }{ {\rm km} }\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} \alpha_1 = 0.000443\, \frac{ {\rm Np} }{ {\rm km \cdot MHz} }\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} \alpha_2 = 0.5984\, \frac{ {\rm Np} }{ {\rm km \cdot \sqrt{MHz} } }\hspace{0.05cm}, \\ \beta_1 & = 22.18\, \frac{ {\rm rad} }{ {\rm km \cdot MHz} }\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} \beta_2 = 0.5984\, \frac{ {\rm rad} }{ {\rm km \cdot \sqrt{MHz} } } \hspace{0.05cm}.\end{align*}$$

These values can be calculated from the geometric dimensions of the cables and have been confirmed by measurements at the Fernmeldetechnisches Zentralamt in Darmstadt - see [Wel77][1]. They apply to a temperature of $20^\circ\ \text{C (293 K)}$ and frequencies greater than $\text{200 kHz}$.

There is the following connection to the »primary line parameters«:

- The ohmic losses originating from the frequency-independent component $R\hspace{0.05cm}'$ are modeled by the parameter $α_0$ and cause a $($for coaxial cables small$)$ frequency-independent attenuation.

- The component $α_1 · f$ of the »attenuation function (per unit length)« is due to the derivation losses $(G\hspace{0.08cm}’)$ and the frequency-proportional term $β_1 · f$ causes only delay but no distortion.

- The components $α_2$ and $β_2$ are due to the »skin effect«, which causes the current density inside the conductor to be lower than at the surface in the case of higher-frequency alternating current. As a result, the »serial resistance (per unit length)« $R\hspace{0.05cm}’$ of an electric line increases with the square root of the frequency.

Characteristic cable attenuation

The graph shows the frequency-dependent attenuation curve for the normal coaxial cable and the small coaxial cable. Shown on the left is the cable attenuation per unit length of the two coaxial cable types in the frequency range up to $\text{500 MHz}$:

- $${\alpha}_{\rm K}(f) \hspace{-0.05cm} = \alpha_0 \hspace{-0.05cm}+ \hspace{-0.05cm} \alpha_1 \cdot f \hspace{-0.05cm}+ \hspace{-0.05cm} \alpha_2 \hspace{-0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{-0.05cm}\sqrt {f} \hspace{0.01cm} \hspace{0.01cm}.$$

- $$\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}{\rm a}_{\rm K}(f) =\alpha_{\rm K}(f) \cdot l $$

Notes on the representation chosen here

- To make the difference between the attenuation function per unit length »alpha« and the function »a« $($after multiplication by length$)$ more recognizable, the attenuation function is written here as ${\rm a}_{\rm K}(f)$ and not $($italics$)$ as ${a}_{\rm K}(f)$.

- The ordinate labeling is given here in »Np/km«. Often it is also done in »dB/km«, with the following conversion:

- $$\ln(10)/20 = 0.11513\text{...} \hspace{0.3cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} 1 \ \rm dB = 0.11513\text{... Np.} $$

Interpretation of the left graph

- It can be seen from the curves shown that the error is still tolerable when neglecting the frequency-independent component $α_0$ and the frequency-proportional term $(α_1\cdot f)$.

- Sometimes, we assume the »simplified attenuation function«:

- $${\rm a}_{\rm K}(f) = \alpha_2 \cdot \sqrt {f} \cdot l = {\rm a}_{\rm \star}\cdot \sqrt { {2f}/{R}} \hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}|H_{\rm K}(f)| = {\rm e}^{- {\rm a}_{\rm K}(f)}\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} {\rm a}_{\rm K}(f)\hspace{0.15cm}{\rm in }\hspace{0.15cm}{\rm Np}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

$\text{Definition:}$ We denote as »characteristic cable attenuation« $\rm a_∗$

- the attenuation of a coaxial cable at half the bit rate

- due to the $α_2$ term alone ⇒ »skin effect«, thus neglecting the $α_0$ and the $α_1$ term:

- $${\rm a}_{\rm \star} = {\rm a}_{\rm K}(f = {R}/{2}) = \alpha_2 \cdot \sqrt {{R}/{2}} \cdot l\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

This value is particularly suitable for comparing different conducted transmission systems with different

- coaxial cable types $($normal or small coaxial cable$)$, each identified by the parameter $\alpha_2$,

- bit rates $(R)$, and

- cable lengths $(l)$.

Interpretation of the right graph

The right–hand diagram above shows the characteristic cable attenuation $\rm a_∗$ in »Neper« $\rm (Np)$ as a function of the bit rate $R$ and the cable length $l$ for

- the normal coaxial cable $\text{(2.6/9.5 mm)}$ ⇒ left ordinate labeling, and

- for the small coaxial cable $\text{(1.2/4.4 mm)}$ ⇒ right ordinate labeling.

This diagram shows the PCM systems of hierarchy levels $3$ to $5$ proposed by the $\text{ITU-T}$ $($»ITU Telecommunication Standardization Sector«$)$ in the 1970s. One recognizes:

- For all these systems for PCM speech transmission, the characteristic cable attenuation assumes values between $7 \ \rm Np \ \ (≈ 61 \ dB)$ and $10.6 \ \rm Np \ \ (≈ 92 \ dB)$ .

- The system $\text{PCM 480}$ – designed for 480 simultaneous telephone calls - with bit rate $R ≈ 35 \ \rm Mbit/s$ was specified for both the normal coaxial cable $($with $l = 9.3 \ \rm km)$ and the small coaxial cable $($with $l = 4 \ \rm km)$. The $\rm a_∗$–values $10.4\ \rm Np$ resp. $9.9\ \rm Np$ are in the same order of magnitude.

- The system $\text{PCM 1920}$ of the fourth hierarchy level $($specified for the normal coaxial cable$)$ with $R ≈ 140 \ \rm Mbit/s$ and $l = 4.65 \ \rm km$ is parameterized by $\rm a_∗ = 10.6 \ \rm Np$ or $10.6 \ {\rm Np}· 8.688 \ \rm dB/Np ≈ 92\ \rm dB$ .

- Although the system $\text{PCM 7680}$ has a four times greater bit rate $R ≈ 560 \ \rm Mbit/s$ , the characteristic cable attenuation of $\rm a_∗ ≈ 61 \ dB$ is due to the better medium »normal coaxial cable« and the shorter cable sections $(l = 1. 55 \ \rm km)$ by a factor of $3$ significantly lower .

- These numerical values also show that for coaxial cable systems, the cable length $l$ is more critical than the bit rate $R$. If one wants to double the cable length, one has to reduce the bit rate by a factor $4$.

You can view the topic described here with the interactive HTLM 5/JavaScript applet »Attenuation of Copper Cables« .

Impulse response of a coaxial cable

To calculate the impulse response, the first two of the in total five components of the complex propagation function $($per unit length$)$ can be neglected $($the reasoning can be found in the previous section$)$. So we start from the following equation:

- $$\gamma(f) = \alpha_0 + \alpha_1 \cdot f + {\rm j} \cdot \beta_1 \cdot f +\alpha_2 \cdot \sqrt {f}+ {\rm j}\cdot \beta_2 \cdot \sqrt {f} \approx {\rm j} \cdot \beta_1 \cdot f +\alpha_2 \cdot \sqrt {f}+ {\rm j}\cdot \beta_2 \cdot \sqrt {f} \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

Considering

- the cable length $l$,

- the characteristic cable attenuation $\rm a_∗$, and

- that $α_2$ $($in »Np«$)$ and $β_2$ (in »rad«$)$ are numerically equal,

thus applies to the »frequency response of the coaxial cable«:

- $$H_{\rm K}(f) = {\rm e}^{-{\rm j}\hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm} b_1 f} \cdot {\rm e}^{-{\rm a}_{\rm \star}\hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm} \sqrt{2f/R} }\cdot {\rm e}^{-{\rm j}\hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm}{\rm a}_{\rm \star}\hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.02cm} \sqrt{2f/R}}= {\rm e}^{-{\rm j}\hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm} b_1 f} \cdot {\rm e}^{-2{\rm a}_{\rm \star}\hspace{0.03cm}\cdot \hspace{0.03cm} \sqrt{ {\rm j}\hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm}f/R}} \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

The following abbreviations are used here:

- $$b_1\hspace{0.1cm}{(\rm in }\hspace{0.15cm}{\rm rad)}= \beta_1 \cdot l \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.8cm} {\rm a}_{\rm \star}\hspace{0.1cm}{(\rm in }\hspace{0.15cm}{\rm Np)}= \alpha_2 \cdot \sqrt {R/2} \cdot l \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

The time domain representation is obtained by applying the »inverse Fourier transform« and the »convolution theorem«:

- $$h_{\rm K}(t) = \mathcal{F}^{-1} \left \{ {\rm e}^{-{\rm j}\hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm} b_1 f}\right \} \star\mathcal{F}^{-1} \left \{ {\rm e}^{-2{\rm a}_{\rm \star}\hspace{0.03cm}\cdot \hspace{0.03cm} \sqrt{ {\rm j}\hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm}f/R} }\right \} \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

It must be taken into account here:

- The first term yields the Dirac delta function $δ(t - τ_{\rm P})$ shifted by the phase delay $τ_{\rm P} = b_1/2π$ .

- The second term can be given analytically closed. We write $h_{\rm K}(t + τ_P)$, so that the phase delay $τ_{\rm P}$ need not be considered further.

- $$h_{\rm K}(t + \tau_{\rm P}) = \frac {{\rm a}_{\rm \star}}{\pi \cdot \sqrt{2 \cdot R \cdot t^3}}\cdot {\rm exp} \left [ -\frac {{\rm a}_{\rm \star}^2}{ {2\pi \cdot R\cdot t}} \right ]\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}{\rm a}_{\rm \star}\hspace{0.15cm}{\rm in\hspace{0.15cm} Np}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- Since the bit rate $R$ also has already been considered in the $\rm a_∗$ definition; this equation can be easily represented with the normalized time $t\hspace{0.05cm}' = t/T$ :

- $$h_{\rm K}(t\hspace{0.05cm}' + \tau_{\rm P}\hspace{0.05cm} ') = \frac {1}{T} \cdot \frac {{\rm a}_{\rm \star}}{\pi \cdot \sqrt{2 \cdot t\hspace{0.05cm}'\hspace{0.05cm}^3}}\cdot {\rm exp} \left [ -\frac {{\rm a}_{\rm \star}^2}{ {2\pi \cdot t\hspace{0.05cm}'}} \right ]\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm}{\rm a}_{\rm \star}\hspace{0.15cm}{\rm in\hspace{0.15cm} Np}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- Here $T = 1/R$ denotes »the symbol duration of a binary system« and it holds $τ_{\rm P} \hspace{0.05cm}' = τ_{\rm P}/T$.

$\text{Example 1:}$ The results of this section are illustrated by the following graph as an example.

- The normalized impulse response $T · h_{\rm K}(t)$ of a coaxial cable with $\rm a_∗ = 60 \ dB \ \ (6.9\ Np)$ is shown.

- The attenuation coefficients $α_0$ and $α_1$ can thus be neglected, as shown in the last section.

- For the left graph, the parameter $β_1 = 0$ was also set.

Because of the parameterization by the coefficient $\rm a_∗$, and the time normalization to the symbol duration $T$ the left curve is equally valid

- for systems with small or normal coaxial cable,

- different lengths,

- different bit rates.

For example for

- normal coaxial cable $\text{2.6/9.5 mm}$, bit rate $R = 140 \ \rm Mbit/s$, cable length $l = 3 \ \rm km$ ⇒ $\text{system A}$,

- small coaxial cable $\text{1.2/4.4 mm}$, bit rate $R = 35 \ \rm Mbit/s$,

cable length $l = 2.8 \ \rm km$ ⇒ $\text{system B}$.

It can be seen in the left–hand diagram that even at this moderate cable attenuation $\rm a_∗ = 60 \ \rm dB$ the impulse response already extends over more than $200$ symbol durations due to the skin effect $(α_2 = β_2 ≠ 0)$. Since the integral over $h_{\rm K}(t)$ is equal to $H_{\rm K}(f = 0) = 1$, the maximum value becomes very small:

- $${\rm Max}\big [h_{\rm K}(t)\big ] \approx 0.03.$$

In the diagram on the right, the effects of the phase parameter $β_1$ can be seen. Note the different time scales of the left and the right diagram:

- For $\text{system A}$ $(β_1 = 21.78 \ \rm rad/(km · MHz)$, $T = 7.14\ \rm ns)$ $β_1$ leads to a phase delay of

- $$\tau_{\rm A}= \frac {\beta_1 \cdot l}{2\pi} =\frac {21.78\, { {\rm rad} }/{ {(\rm km \cdot MHz)} }\cdot 3\,{\rm km} }{2\pi} = 10.4\,{\rm \mu s}\hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}\tau_{\rm A}\hspace{0.05cm}' = {\tau_{\rm A} }/{T} \approx 1457\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- On the other hand, the following can be obtained for $\text{system B}$ $(β_1 = 22.18 \ \rm rad/(km · MHz)$, $T = 30 \ \rm ns)$:

- $$\tau_{\rm B}= \frac {\beta_1 \cdot l}{2\pi} =\frac {22.18\, { {\rm rad} }/{ {(\rm km \cdot MHz)} }\cdot 2.8\,{\rm km} }{2\pi} = 9.9\,{\rm µ s}\hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}\tau_{\rm B}\hspace{0.05cm}' ={\tau_{\rm B} }/{T} \approx 330\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

Although $τ_{\rm A} ≈ τ_{\rm B}$ holds, completely different ratios result because of the time normalization to $T = 1/R$ .

$\text{Conclusion:}$ When simulating and optimizing transmission systems,

one usually omits the linear phase term $b_1 = β_1 · f$, since this results exclusively in a $($often not disturbing$)$ phase delay, but no signal distortions.

Basic receiver pulse

With the »basic transmission pulse« $g_s(t)$ ⇒ »basic pulse of the transmitted signal« $s(t)$ and the »impulse response $h_{\rm K}(t)$ of the channel, the result for the »basic receiver pulse« $g_r(t)$ ⇒ »basic pulse of the received signal« $r(t)$ is:

- $$g_r(t) = g_s(t) \star h_{\rm K}(t)\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

If a non-return-to-zero $\rm (NRZ)$ rectangular pulse $g_s(t)$ with amplitude $s_0$ and duration $Δt_s = T$ is used at the transmitter, the following results for the basic pulse at the receiver input:

- $$g_r(t) = 2 s_0 \cdot \left [ {\rm Q} \left (\frac {{\rm a}_{\rm \star}/\sqrt {\pi}}{ \sqrt{ (t/T - 0.5)}}\right ) - {\rm Q} \left (\frac {{\rm a}_{\rm \star}/\sqrt {\pi}}{ \sqrt{ (t/T + 0.5)}}\right ) \right ]\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

Here $\rm a_∗$ denotes the »characteristic cable attenuation« $($in Neper$)$ and ${\rm Q}(x)$ the »complementary Gaussian error function«.

$\text{Example 2:}$ The figure shows for the characteristic cable attenuations $\rm a_∗ = 40 \ \rm dB$, ... , $100 \ \rm dB$ $($smaller $\rm a_∗$–values are not relevant for practice$)$

- the normalized coaxial cable impulse response $T · h_{\rm K}(t)$ ⇒ solid curves,

- the basic receiver pulse $($»rectangular response«$)$ $g_r(t)$ normalized to the transmission amplitude $s_0$ ⇒ dotted line.

One recognizes the following from this diagram:

- With $\rm a_∗ = 40 \ \rm dB$, the normalized basic receiver pulse $g_r(t)/s_0$ is at the peak slightly $($about a factor of $0.95)$ smaller than the normalized impulse response $T · h_{\rm K}(t)$. Here is a small difference between impulse response and basic receiver pulse .

- In contrast, for $a_∗ ≥ 60 \ \rm dB$, the basic receiver pulse and the impulse response are indistinguishable within the drawing accuracy.

- For a return-to-zero $\rm (RZ)$ pulse, the above equation for $g_r(t)$ would still need to be multiplied by the factor $Δt_s/T$. In this case $g_r(t)/s_0$ is smaller than $T · h_{\rm K}(t)$ by at least this factor.

- The equation modified in this way is also a good approximation for other basic transmission pulses as long as $\rm a_∗≥ 60 \ \rm dB$ is sufficiently large. $Δt_s$ then indicates the »equivalent pulse duration« of $g_r(t)$.

Special features of coaxial cable systems

Assuming binary transmission

- with non-return-to-zero $\rm (NRZ)$ rectangular pulses $($duration $T)$

- and a coaxial transmission channel,

the following system model is obtained. In particular, it should be noted:

$(1)$ In a simulation, the phase delay time of the coaxial cable is conveniently left out of consideration. Then the basic receiver pulse $g_r(t)$ is approximated by $($with ${\rm a}_{\rm \star}$ in Neper$)$:

- $$g_r(t) \approx s_0 \cdot T \cdot h_{\rm K}(t) = \frac {s_0 \cdot {\rm a}_{\rm \star}/\pi}{ \sqrt{2 \cdot(t/T)^3}}\cdot {\rm e}^{ -{{\rm a}_{\rm \star}^2}/( {2\pi \hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm}t/T}) } \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

$(2)$ Because of the good shielding of coaxial cables against other impairments, the »thermal noise« is the dominant stochastic perturbation. In this case, the signal $n(t)$ is Gaussian and white. It can described by the $($two-sided$)$ noise power density $N_0/2$.

$(3)$ By far the largest noise component arises in the input stage of the receiver, so that it is expedient to add the noise signal $n(t)$ at the interface »cable ⇒ receiver«. This noise addition point is also useful because the frequency response $H_{\rm K}(f)$ decisively attenuates all noise accumulated along the cable.

$(3)$ Then the received signal is with the amplitude coefficients $a_{\nu}$:

- $$r(t) = \sum_{\nu = - \infty}^{+ \infty}a_{\nu}\cdot g_r(t - \nu \cdot T)+ n(t) \hspace{0.05cm} .$$

Exercises for the chapter

Exercise 4.4: Coaxial Cable - Frequency Response

Exercise 4.5: Coaxial Cable - Impulse Response

Exercise 4.5Z: Impulse Response once again

References

- ↑ Wellhausen, H. W.: Dämpfung, Phase und Laufzeiten bei Weitverkehrs–Koaxialpaaren. Frequenz 31, S. 23-28, 1977.