Difference between revisions of "Modulation Methods/Single-Sideband Modulation"

| (60 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Header | {{Header | ||

| − | |Untermenü= | + | |Untermenü=Amplitude Modulation and Demodulation |

| − | |Vorherige Seite= | + | |Vorherige Seite=Envelope Demodulation |

| − | |Nächste Seite= | + | |Nächste Seite=Further AM Variants |

}} | }} | ||

| − | == | + | ==Description in the frequency domain== |

| − | + | <br> | |

| − | * | + | Double sideband amplitude modulation $\rm (DSB–AM)$ – both with and without a carrier – has the following characteristics: |

| − | * | + | *The modulated signal $s(t)$ requires twice the bandwidth of the source signal $q(t)$. |

| + | |||

| + | *The complete information about $q(t)$ is in both the upper sideband $\rm (USB)$ as well as in the lower sideband $\rm (LSB)$. | ||

| − | + | The so-called »'''single-sideband amplitude modulation'''« $\rm (SSB–AM)$ takes advantage of this property by transmitting only one of these sidebands, either the upper sideband (USB) or the lower sideband (LSB). This reduces the required bandwidth by half compared to DSB-AM. | |

| + | The graph illustrates single-sideband amplitude modulation in the frequency domain and simultaneously presents a realization of a SSB modulator. | ||

| − | + | In this representation, one can see: | |

| + | [[File:EN_Mod_T_2_4_S1.png|right|frame| Spectra for double sideband $\rm (DSB)$ and single-sideband $\rm (USB, LSB)$ modulation]] | ||

| − | + | *The SSB spectrum results from the DSB spectrum by filtering with a band-pass which displays asymmetrical behaviour with respect to the carrier frequency $f_{\rm T}$. | |

| − | * | + | |

| − | * | + | *For upper sideband modulation $\rm (USB)$, the lower cutoff frequency is chosen at $f_{\rm U} = f_{\rm T} - f_ε$ and $f_{\rm O} ≥ f_{\rm T} + B_{\rm NF}$ $($subscripts from the German: "U" ⇒ "untere" ⇒ "lower", and "O" ⇒ "obere" ⇒ "upper"$)$. Here, $f_ε$ denotes an arbitrarily small positive frequency. |

| − | + | ||

| + | *Thus, the USB spectrum only contains the upper sideband and the carrier (though not necessarily the latter). To generate an USB modulation, the upper and lower cutoff frequencies of the band-pass must be set as follows: | ||

| + | :$$f_{\rm U} ≤ f_{\rm T} \ - \ B_{\rm NF}, \hspace{0.5cm}f_{\rm O} = f_{\rm T} + f_ε.$$ | ||

| + | <br clear=all> | ||

| + | {{GraueBox|TEXT= | ||

| + | $\text{Example 1:}$ For $f_{\rm T} = 100 \ \rm kHz$, $B_{\rm NF} = 3 \ \rm kHz$ , DSB gives us an "USB-AM with carrier" if the filter cuts out all frequencies below $99.999\text{...} \ \rm kHz$ . | ||

| + | *If the lower cut-off frequency $f_{\rm U}$ is larger than $f_{\rm T}$ by an (arbitrarily) small "epsilon", we get an "USB-AM without carrier". | ||

| + | |||

| + | *A "LSB with/without carrier" can be realised accordingly with $f_{\rm O} =100 \ \rm kHz$ and $f_{\rm O} = 99.999\text{...} \ \rm kHz$, resp. }} | ||

| + | {{GraueBox|TEXT= | ||

| + | $\text{Example 2:}$ To save bandwidth, single-sideband technology was already used in the 1960s for the analog transmission of telephone calls. | ||

| + | *In accordance with a hierarchical structure, three telephone channels – each band-limited to the range from $300\ \rm Hz$ to $3.4 \ \rm kHz$ – were initially combined to form a preliminary grouping with a bandwidth of $12 \ \rm kHz$ . | ||

| + | *In order to be able to accommodate three channels in $12 \ \rm kHz$ with a safety margin, only one sideband (LSB or USB) of each telephone channel was considered. | ||

| − | + | *Using further combinations, the long distance traffic system »'''V10800'''« with up to $10800$ voice channels and a total bandwidth of $60 \ \rm MHz$ was thus realized.}} | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | {{BlaueBox|TEXT= | |

| − | { | + | $\text{Conclusion:}$ |

| + | *The great advantage of a $\rm SSB-AM$ is that it has »'''half the bandwidth'''« compared to $\rm DSB-AM$. | ||

| − | + | *The trade-off with disadvantages required for this advantage is explained in the next sections.}} | |

| − | |||

| − | [[ | + | ==Synchronous demodulation of a SSB-AM signal== |

| + | <br> | ||

| + | Let us now consider a SSB-AM modulated signal and a [[Modulation_Methods/Synchronous_Demodulation|$\text{synchronous demodulator}$]] at the receiver. | ||

| + | *Perfect frequency and phase synchronization will be assumed. | ||

| + | *Without affecting generality, in the rest of this section we will always let ${ ϕ}_{\rm T} = 0$ ⇒ cosine carrier. | ||

| − | + | [[File:EN_Mod_T_2_4_S2_neu.png |right|frame| Synchronous demodulation of a SSB-AM signal]] | |

| − | + | <br> | |

| − | + | A comparison with the [[Modulation_Methods/Synchronous_Demodulation|$\text{characteristics of the synchronous demodulator for DSB-AM}$]] shows the follows similarities and differences: | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *The spectrum $V(f)$ of the sink signal results in both cases from the convolution of the spectra $R(f)$ and $Z_{\rm E}(f)$, the latter being composed of two Dirac delta functions at $±f_{\rm T}$. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | *For SSB–AM the convolution products overlap with the left and the right Dirac delta function at every frequency. These are denoted by "+" and "–" respectively in the [[Modulation_Methods/Synchronous_Demodulation#Description_in_the_frequency_domain|$\text{corresponding DSB graph}$]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | & | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | *In contrast, for USB, only the convolution with the Dirac delta line at $ -f_{\rm T}$ yields the $V(f)$ component for positive frequencies, and for LSB modulation it is the convolution with the Dirac delta function $δ(f - f_{\rm T})$. | |

| − | * | + | |

| − | + | *In the case of DSB–AM, $v(t) = q(t)$ is reached with the receiver-side carrier signal $z_{\rm E}(t) = 2 · \cos(ω_{\rm T} · t)$. In contrast, the carrier amplitude must be increased to $A_{\rm T} = 4$ for SSB-AM. | |

| + | <br clear=all> | ||

| + | {{BlaueBox|TEXT= | ||

| + | $\text{Conclusion:}$ If there is a frequency offset between the carrier signals $z(t)$ and $z_{\rm E}(t)$, strong nonlinear distortion always occurs, i.e., regardless of whether DSB-AM or SSB-AM is present. For the »'''implementation of a synchronous demodulator'''« a »'''perfect frequency synchronization'''« is essential. }} | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Influence of a phase offset for SSB-AM== | |

| + | <br> | ||

| + | Let us now consider the influence of a phase offset $Δ{\mathbf ϕ}_{\rm T}$ between the transmitter and receiver side carrier signals, using an example source signal | ||

| + | :$$q(t) = A_1 \cdot \cos(\omega_1 \cdot t ) + A_2 \cdot \cos(\omega_2 \cdot t)\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| + | *For DSB–AM, such a phase offset only leads to frequency-independent attenuation, but not to distortions: | ||

| + | :$$v(t) = \cos (\Delta \phi_{\rm T}) \cdot q(t) = \cos (\Delta \phi_{\rm T}) \cdot A_1 \cdot \cos(\omega_1 \cdot t ) + \cos (\Delta \phi_{\rm T}) \cdot A_2 \cdot \cos(\omega_2 \cdot t ) \hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| − | + | *In contrast, for USB-AM we get: | |

| − | + | :$$v(t) = A_1 \cdot \cos(\omega_1 \cdot t - \Delta \phi_{\rm T}) + A_2 | |

| − | + | \cdot \cos(\omega_2 \cdot t - \Delta \phi_{\rm T})= A_1 \cdot \cos(\omega_1 \cdot (t - \tau_1)) + A_2 \cdot | |

| + | \cos(\omega_2 \cdot (t - \tau_2))\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| − | + | {{BlaueBox|TEXT= | |

| − | $ | + | $\text{From this equation we can see:}$ |

| − | + | *The two delay times $τ_1 = Δ{\mathbf ϕ}_{\rm T}/ω_1$ and $τ_2 = Δ{\mathbf ϕ}_{\rm T}/ω_2$ are different. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | *This means that a phase offset in single sideband amplitude modulation (USB–AM or LSB–AM) leads to »'''phase distortions'''« (i.e., to linear distortions). | |

| − | $ | + | |

| − | + | *A positive value of $Δ{\mathbf ϕ}_{\rm T}$ will cause | |

| − | $$ | + | **positive values of $τ_1$ and $τ_2$ (i.e., lagging signals with respect to the cosine) for USB, and |

| − | + | **negative $τ_1$ and $τ_2$ values (leading signals) for LSB.}} | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | The effects of phase distortions on a signal composed two cosine oscillations is illustrated with the HTML 5/JavaScript applet [[Applets:Linear_Distortions_of_Periodic_Signals|"Linear Distortions of Periodic Signals"]]. | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | ==Sideband-to-carrier ratio== | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | An important parameter for DSB–AM is the [[Modulation_Methods/Double-Sideband_Amplitude_Modulation#Double-Sideband_Amplitude_Modulation_with_carrier|$\text{modulation depth}$]] $m = q_{\rm max}/A_{\rm T}$. In the special case of a harmonic oscillation, $m = A_{\rm N}/A_{\rm T}$ holds and one obtains the spectrum $S_+(f)$ of the analytical signal corresponding to the upper graph. Please note the normalization with respect to $A_{\rm T}$. | ||

| − | + | [[File:EN_Mod_T_2_4_S4a.png|right|frame|Spectra for DSB-AM, USB-AM]] | |

| − | + | For SSB–AM, the application of the parameter $m$ is possible in principle, but it is not practical. | |

| − | + | For example, the following holds for the time-domain representation of USB-AM with the spectrum $S_+(f)$ corresponding to the lower graph: | |

| − | + | :$$s_+(t) = A_{\rm T} \cdot {\rm e}^{{\rm j}\hspace{0.03cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm} \omega_{\rm T} \hspace{0.03cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm}t } + {A_{\rm N}}/{2} \cdot {\rm e}^{{\rm j}\hspace{0.03cm}\cdot \hspace{0.03cm} (\omega_{\rm T} + \omega_{\rm N}) \hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm}t }\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | |

| − | * | + | In a similar way, this can be written as |

| + | :$$s_+(t) = A_{\rm T} \cdot \left({\rm e}^{{\rm j}\hspace{0.03cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm} \omega_{\rm T} \hspace{0.03cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm}t } + \mu \cdot {\rm e}^{{\rm j}\hspace{0.03cm}\cdot \hspace{0.03cm} (\omega_{\rm T} + \omega_{\rm N}) \hspace{0.03cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm}t }\right)$$ | ||

| + | now using the »'''sideband–to–carrier ratio'''« : | ||

| + | :$$\mu = \frac{A_{\rm N}}{2 \cdot A_{\rm T}} \hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| + | If the source signal is not a harmonic oscillation, it is difficult to specify this quantity. | ||

| + | *Here one can use the following approximation: | ||

| + | :$$\mu \approx \frac{q_{\rm max}}{2 \cdot A_{\rm T}} \hspace{0.3cm}{\rm with}\hspace{0.3cm} q_{\rm max} = \max_{t} \hspace{0.05cm} |q(t)| \hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| + | *Thus, $\mu \approx m/2.$ However, a comparison of DSB-AM to SSB-AM should always be made for the same numerical value of $m$ and $,\mu$ resp. | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | {{GraueBox|TEXT= | |

| − | + | [[File:EN_Mod_T_2_4_S4b.png |right|frame| Signal waveforms for DSB-AM and USB-AM]] | |

| + | $\text{Example 3:}$ | ||

| + | *The upper graph shows the DSB-AM signal for a modulation depth of $m = q_{\rm max}/A_{\rm T} = 1$ ⇒ limit case for the application of envelope demodulation with DSB-AM ⇒ The signal $q(t)$ is then just contained in the envelope $a(t)$. | ||

| − | + | *For the USB-AM signal in the middle graph, $A_{\rm T} = q_{\rm max}$ was also chosen which corresponds to the numerical values $m = 1$ and $\mu = 0.5$ as defined above ⇒ Since the LSB magnitude is missing, the envelope $a(t)$ is significantly different to $q(t) + A_{\rm T}.$ | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | *In contrast, $q_{\rm max} = 2 · A_{\rm T}$ was chosen for the lower signal waveform ⇒ Here, the sideband-to-carrier ratio has the numerical value $\mu =1$. | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | * | + | This graph makes the following clear: |

| − | * | + | #There are more similarities between the upper and lower signal than between the first two. |

| − | * | + | #The comparison of a DSB-AM and a SSB-AM should be made for the same numerical value of $m$ and $\mu$ if possible. |

| − | * | + | #For each value $\mu$ of the sideband-to-carrier ratio, the envelope demodulation with SSB-AM leads to severe distortions. |

| + | #These are of a nonlinear nature and therefore irreversible. }} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Summarized evaluation of SSB–AM== | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | The key advantage of $\text{SSB–AM}$ compared to $\text{DSB–AM}$ is the bandwidth requirement, smaller by a factor of $2$. However, for the half bandwidth in SSB-AM, some disadvantages have to be accepted, which will be investigated in the exercises for this section: | ||

| + | *The information about the source signal $q(t)$ is, in contrast to DSB-AM, no longer exclusively in the amplitude, but equally in the phase (see [[Aufgaben:Exercise_2.11:_Envelope_Demodulation_of_an_SSB_Signal|"Exercise 2.11"]]). | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Synchronous demodulation of a SSB–AM signal leads to phase distortions if there is a phase offset between the carrier signals at the transmitter and the receiver. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *The application of $\text{envelope demodulation}$ with "USB–AM" or "LSB–AM" thus always leads to strong nonlinear distortions (see [[Aufgaben:Exercise_2.11Z:_Once_again_SSB-AM_and_Envelope_Demodulator|"Exercise 2.11Z"]]). | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | As with DSB–AM and synchronous demodulation, the following statements also apply here: | ||

| + | *Attenuation distortions of the channel also lead only to (linear) attenuation distortions with respect to the sink signal. No nonlinear distortions arise (see [[Aufgaben:Exercise_2.10:_SSB-AM_with_Channel_Distortions|"Exercise 2.10"]]). | ||

| + | |||

| + | *SSB–AM without a carrier shows the exact same noise behaviour as DSB-AM without a carrier. The advantage of the smaller RF bandwidth is cancelled out by the necessary level matching. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *A SSB–AM with a sideband-to-carrier ratio $\mu$ shows similar noise behaviour as in DSB-AM with modulation depth $m = \sqrt{2} · \mu$ (see [[Aufgaben:Exercise_2.10Z:_Noise_with_DSB-AM_and_SSB-AM|"Exercise 2.10Z"]]). | ||

| + | |||

| + | *In any case, it should be noted that SSB-AM with carrier is not very useful due to the nonlinear distortions brought about with envelope demodulation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==Exercises for the chapter== | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | [[Aufgaben:Exercise_2.10:_SSB-AM_with_Channel_Distortions|Exercise 2.10: SSB-AM with Channel Distortions]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Aufgaben:Exercise_2.10Z:_Noise_with_DSB-AM_and_SSB-AM|Exercise 2.10Z: Noise with DSB-AM and SSB-AM]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Aufgaben:Exercise_2.11:_Envelope_Demodulation_of_an_SSB_Signal|Exercise 2.11: Envelope Demodulation of an SSB signal]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Aufgaben:Exercise_2.11Z:_Once_again_SSB-AM_and_Envelope_Demodulator|Exercise 2.11Z: Once again SSB-AM and Envelope Demodulator]] | ||

{{Display}} | {{Display}} | ||

Latest revision as of 14:43, 18 January 2023

Contents

Description in the frequency domain

Double sideband amplitude modulation $\rm (DSB–AM)$ – both with and without a carrier – has the following characteristics:

- The modulated signal $s(t)$ requires twice the bandwidth of the source signal $q(t)$.

- The complete information about $q(t)$ is in both the upper sideband $\rm (USB)$ as well as in the lower sideband $\rm (LSB)$.

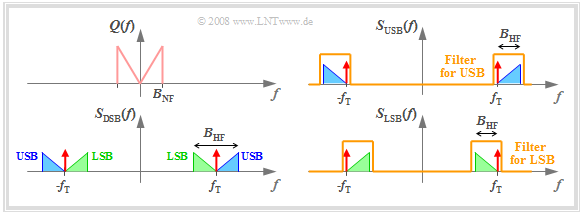

The so-called »single-sideband amplitude modulation« $\rm (SSB–AM)$ takes advantage of this property by transmitting only one of these sidebands, either the upper sideband (USB) or the lower sideband (LSB). This reduces the required bandwidth by half compared to DSB-AM.

The graph illustrates single-sideband amplitude modulation in the frequency domain and simultaneously presents a realization of a SSB modulator.

In this representation, one can see:

- The SSB spectrum results from the DSB spectrum by filtering with a band-pass which displays asymmetrical behaviour with respect to the carrier frequency $f_{\rm T}$.

- For upper sideband modulation $\rm (USB)$, the lower cutoff frequency is chosen at $f_{\rm U} = f_{\rm T} - f_ε$ and $f_{\rm O} ≥ f_{\rm T} + B_{\rm NF}$ $($subscripts from the German: "U" ⇒ "untere" ⇒ "lower", and "O" ⇒ "obere" ⇒ "upper"$)$. Here, $f_ε$ denotes an arbitrarily small positive frequency.

- Thus, the USB spectrum only contains the upper sideband and the carrier (though not necessarily the latter). To generate an USB modulation, the upper and lower cutoff frequencies of the band-pass must be set as follows:

- $$f_{\rm U} ≤ f_{\rm T} \ - \ B_{\rm NF}, \hspace{0.5cm}f_{\rm O} = f_{\rm T} + f_ε.$$

$\text{Example 1:}$ For $f_{\rm T} = 100 \ \rm kHz$, $B_{\rm NF} = 3 \ \rm kHz$ , DSB gives us an "USB-AM with carrier" if the filter cuts out all frequencies below $99.999\text{...} \ \rm kHz$ .

- If the lower cut-off frequency $f_{\rm U}$ is larger than $f_{\rm T}$ by an (arbitrarily) small "epsilon", we get an "USB-AM without carrier".

- A "LSB with/without carrier" can be realised accordingly with $f_{\rm O} =100 \ \rm kHz$ and $f_{\rm O} = 99.999\text{...} \ \rm kHz$, resp.

$\text{Example 2:}$ To save bandwidth, single-sideband technology was already used in the 1960s for the analog transmission of telephone calls.

- In accordance with a hierarchical structure, three telephone channels – each band-limited to the range from $300\ \rm Hz$ to $3.4 \ \rm kHz$ – were initially combined to form a preliminary grouping with a bandwidth of $12 \ \rm kHz$ .

- In order to be able to accommodate three channels in $12 \ \rm kHz$ with a safety margin, only one sideband (LSB or USB) of each telephone channel was considered.

- Using further combinations, the long distance traffic system »V10800« with up to $10800$ voice channels and a total bandwidth of $60 \ \rm MHz$ was thus realized.

$\text{Conclusion:}$

- The great advantage of a $\rm SSB-AM$ is that it has »half the bandwidth« compared to $\rm DSB-AM$.

- The trade-off with disadvantages required for this advantage is explained in the next sections.

Synchronous demodulation of a SSB-AM signal

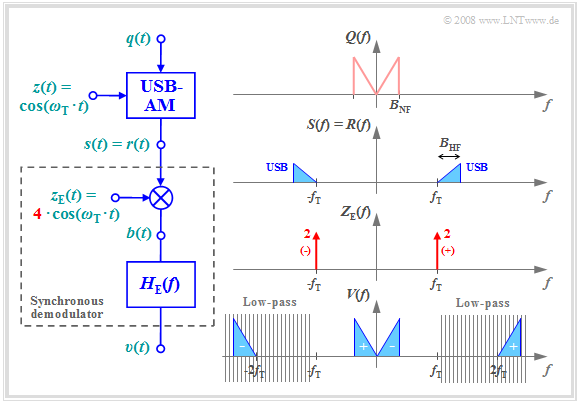

Let us now consider a SSB-AM modulated signal and a $\text{synchronous demodulator}$ at the receiver.

- Perfect frequency and phase synchronization will be assumed.

- Without affecting generality, in the rest of this section we will always let ${ ϕ}_{\rm T} = 0$ ⇒ cosine carrier.

A comparison with the $\text{characteristics of the synchronous demodulator for DSB-AM}$ shows the follows similarities and differences:

- The spectrum $V(f)$ of the sink signal results in both cases from the convolution of the spectra $R(f)$ and $Z_{\rm E}(f)$, the latter being composed of two Dirac delta functions at $±f_{\rm T}$.

- For SSB–AM the convolution products overlap with the left and the right Dirac delta function at every frequency. These are denoted by "+" and "–" respectively in the $\text{corresponding DSB graph}$.

- In contrast, for USB, only the convolution with the Dirac delta line at $ -f_{\rm T}$ yields the $V(f)$ component for positive frequencies, and for LSB modulation it is the convolution with the Dirac delta function $δ(f - f_{\rm T})$.

- In the case of DSB–AM, $v(t) = q(t)$ is reached with the receiver-side carrier signal $z_{\rm E}(t) = 2 · \cos(ω_{\rm T} · t)$. In contrast, the carrier amplitude must be increased to $A_{\rm T} = 4$ for SSB-AM.

$\text{Conclusion:}$ If there is a frequency offset between the carrier signals $z(t)$ and $z_{\rm E}(t)$, strong nonlinear distortion always occurs, i.e., regardless of whether DSB-AM or SSB-AM is present. For the »implementation of a synchronous demodulator« a »perfect frequency synchronization« is essential.

Influence of a phase offset for SSB-AM

Let us now consider the influence of a phase offset $Δ{\mathbf ϕ}_{\rm T}$ between the transmitter and receiver side carrier signals, using an example source signal

- $$q(t) = A_1 \cdot \cos(\omega_1 \cdot t ) + A_2 \cdot \cos(\omega_2 \cdot t)\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- For DSB–AM, such a phase offset only leads to frequency-independent attenuation, but not to distortions:

- $$v(t) = \cos (\Delta \phi_{\rm T}) \cdot q(t) = \cos (\Delta \phi_{\rm T}) \cdot A_1 \cdot \cos(\omega_1 \cdot t ) + \cos (\Delta \phi_{\rm T}) \cdot A_2 \cdot \cos(\omega_2 \cdot t ) \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- In contrast, for USB-AM we get:

- $$v(t) = A_1 \cdot \cos(\omega_1 \cdot t - \Delta \phi_{\rm T}) + A_2 \cdot \cos(\omega_2 \cdot t - \Delta \phi_{\rm T})= A_1 \cdot \cos(\omega_1 \cdot (t - \tau_1)) + A_2 \cdot \cos(\omega_2 \cdot (t - \tau_2))\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

$\text{From this equation we can see:}$

- The two delay times $τ_1 = Δ{\mathbf ϕ}_{\rm T}/ω_1$ and $τ_2 = Δ{\mathbf ϕ}_{\rm T}/ω_2$ are different.

- This means that a phase offset in single sideband amplitude modulation (USB–AM or LSB–AM) leads to »phase distortions« (i.e., to linear distortions).

- A positive value of $Δ{\mathbf ϕ}_{\rm T}$ will cause

- positive values of $τ_1$ and $τ_2$ (i.e., lagging signals with respect to the cosine) for USB, and

- negative $τ_1$ and $τ_2$ values (leading signals) for LSB.

The effects of phase distortions on a signal composed two cosine oscillations is illustrated with the HTML 5/JavaScript applet "Linear Distortions of Periodic Signals".

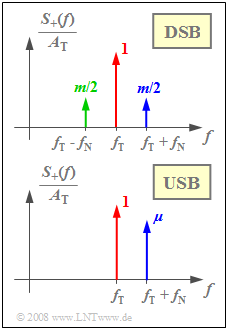

Sideband-to-carrier ratio

An important parameter for DSB–AM is the $\text{modulation depth}$ $m = q_{\rm max}/A_{\rm T}$. In the special case of a harmonic oscillation, $m = A_{\rm N}/A_{\rm T}$ holds and one obtains the spectrum $S_+(f)$ of the analytical signal corresponding to the upper graph. Please note the normalization with respect to $A_{\rm T}$.

For SSB–AM, the application of the parameter $m$ is possible in principle, but it is not practical.

For example, the following holds for the time-domain representation of USB-AM with the spectrum $S_+(f)$ corresponding to the lower graph:

- $$s_+(t) = A_{\rm T} \cdot {\rm e}^{{\rm j}\hspace{0.03cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm} \omega_{\rm T} \hspace{0.03cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm}t } + {A_{\rm N}}/{2} \cdot {\rm e}^{{\rm j}\hspace{0.03cm}\cdot \hspace{0.03cm} (\omega_{\rm T} + \omega_{\rm N}) \hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm}t }\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

In a similar way, this can be written as

- $$s_+(t) = A_{\rm T} \cdot \left({\rm e}^{{\rm j}\hspace{0.03cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm} \omega_{\rm T} \hspace{0.03cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm}t } + \mu \cdot {\rm e}^{{\rm j}\hspace{0.03cm}\cdot \hspace{0.03cm} (\omega_{\rm T} + \omega_{\rm N}) \hspace{0.03cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm}t }\right)$$

now using the »sideband–to–carrier ratio« :

- $$\mu = \frac{A_{\rm N}}{2 \cdot A_{\rm T}} \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

If the source signal is not a harmonic oscillation, it is difficult to specify this quantity.

- Here one can use the following approximation:

- $$\mu \approx \frac{q_{\rm max}}{2 \cdot A_{\rm T}} \hspace{0.3cm}{\rm with}\hspace{0.3cm} q_{\rm max} = \max_{t} \hspace{0.05cm} |q(t)| \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- Thus, $\mu \approx m/2.$ However, a comparison of DSB-AM to SSB-AM should always be made for the same numerical value of $m$ and $,\mu$ resp.

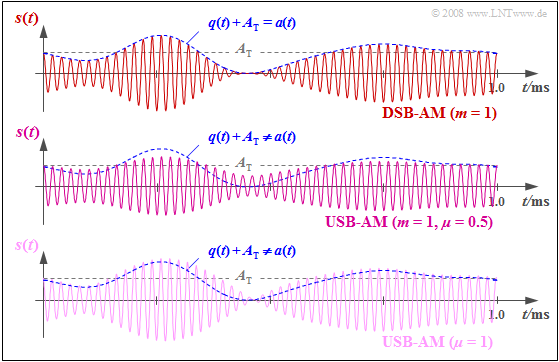

$\text{Example 3:}$

- The upper graph shows the DSB-AM signal for a modulation depth of $m = q_{\rm max}/A_{\rm T} = 1$ ⇒ limit case for the application of envelope demodulation with DSB-AM ⇒ The signal $q(t)$ is then just contained in the envelope $a(t)$.

- For the USB-AM signal in the middle graph, $A_{\rm T} = q_{\rm max}$ was also chosen which corresponds to the numerical values $m = 1$ and $\mu = 0.5$ as defined above ⇒ Since the LSB magnitude is missing, the envelope $a(t)$ is significantly different to $q(t) + A_{\rm T}.$

- In contrast, $q_{\rm max} = 2 · A_{\rm T}$ was chosen for the lower signal waveform ⇒ Here, the sideband-to-carrier ratio has the numerical value $\mu =1$.

This graph makes the following clear:

- There are more similarities between the upper and lower signal than between the first two.

- The comparison of a DSB-AM and a SSB-AM should be made for the same numerical value of $m$ and $\mu$ if possible.

- For each value $\mu$ of the sideband-to-carrier ratio, the envelope demodulation with SSB-AM leads to severe distortions.

- These are of a nonlinear nature and therefore irreversible.

Summarized evaluation of SSB–AM

The key advantage of $\text{SSB–AM}$ compared to $\text{DSB–AM}$ is the bandwidth requirement, smaller by a factor of $2$. However, for the half bandwidth in SSB-AM, some disadvantages have to be accepted, which will be investigated in the exercises for this section:

- The information about the source signal $q(t)$ is, in contrast to DSB-AM, no longer exclusively in the amplitude, but equally in the phase (see "Exercise 2.11").

- Synchronous demodulation of a SSB–AM signal leads to phase distortions if there is a phase offset between the carrier signals at the transmitter and the receiver.

- The application of $\text{envelope demodulation}$ with "USB–AM" or "LSB–AM" thus always leads to strong nonlinear distortions (see "Exercise 2.11Z").

As with DSB–AM and synchronous demodulation, the following statements also apply here:

- Attenuation distortions of the channel also lead only to (linear) attenuation distortions with respect to the sink signal. No nonlinear distortions arise (see "Exercise 2.10").

- SSB–AM without a carrier shows the exact same noise behaviour as DSB-AM without a carrier. The advantage of the smaller RF bandwidth is cancelled out by the necessary level matching.

- A SSB–AM with a sideband-to-carrier ratio $\mu$ shows similar noise behaviour as in DSB-AM with modulation depth $m = \sqrt{2} · \mu$ (see "Exercise 2.10Z").

- In any case, it should be noted that SSB-AM with carrier is not very useful due to the nonlinear distortions brought about with envelope demodulation.

Exercises for the chapter

Exercise 2.10: SSB-AM with Channel Distortions

Exercise 2.10Z: Noise with DSB-AM and SSB-AM

Exercise 2.11: Envelope Demodulation of an SSB signal

Exercise 2.11Z: Once again SSB-AM and Envelope Demodulator