Difference between revisions of "Modulation Methods/Synchronous Demodulation"

m |

m |

||

| Line 268: | Line 268: | ||

*For the system variant „DSB–AM without a carrier” with $m → ∞$ the above equation yields the simple relationship $ρ_v = ξ$. This gives the bisector of the angle for both the linear and double logarithmic plots. | *For the system variant „DSB–AM without a carrier” with $m → ∞$ the above equation yields the simple relationship $ρ_v = ξ$. This gives the bisector of the angle for both the linear and double logarithmic plots. | ||

*A greater transmission power $P_{\rm S}$ leads to a better sink SNR, as does a larger transmission factor $α_{\rm K}$ (⇒ lower attenuation).However, $10 · \lg ρ_v$ is also increased by a smaller noise power density $N_0$ and a smaller bandwidth $B_{\rm NF}$ , other things being equal. | *A greater transmission power $P_{\rm S}$ leads to a better sink SNR, as does a larger transmission factor $α_{\rm K}$ (⇒ lower attenuation).However, $10 · \lg ρ_v$ is also increased by a smaller noise power density $N_0$ and a smaller bandwidth $B_{\rm NF}$ , other things being equal. | ||

| − | * | + | *For "DSB–AM with carrier” with a modulation depth $m$: |

:$$\rho_v = \xi \cdot \frac{1}{1 + {2}/{m^2}}\hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} | :$$\rho_v = \xi \cdot \frac{1}{1 + {2}/{m^2}}\hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} | ||

10 \cdot {\rm lg }\hspace{0.1cm}\rho_v = 10 \cdot {\rm lg }\hspace{0.1cm}\xi - 10 \cdot {\rm lg }\hspace{0.1cm} \left({1 + {2}/{m^2}}\right)\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | 10 \cdot {\rm lg }\hspace{0.1cm}\rho_v = 10 \cdot {\rm lg }\hspace{0.1cm}\xi - 10 \cdot {\rm lg }\hspace{0.1cm} \left({1 + {2}/{m^2}}\right)\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| − | *In | + | *In the double logarithmic representation (see right graph), this leads to a downward parallel shift of the curves, for example at $m = 1$ by $4.77$ dB  and at $m = 0.5$ by $9.54$ dB. |

| − | * | + | *All statements are valid under the assumption of an ideal synchronous demodulator. In this case, the "DSB-AM with carrier" method actually makes no sense. The added carrier would only lead to an unnecessarily large transmit power and could not be used for demodulation. |

| − | * | + | *The curves are valid for perfect frequency and phase synchronization. However, in order to be able to determine the parameters 𝑓 $f_{\rm T}$ and $\mathbf{ϕ_{\rm T} }$ from the received signal $r(t)$ with less effort, a small carrier component in the transmitted signal makes sense. |

| − | * | + | *When $m = 3$ , it is only an insignifican deterioration of less than one dB compared to "DSB-AM without carrier". |

| − | == | + | ==Exercises for the Chapter== |

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | [[Aufgaben:Aufgabe_2.4:_Frequenz–_und_Phasenversatz| | + | [[Aufgaben:Aufgabe_2.4:_Frequenz–_und_Phasenversatz|Exercise 2.4: Frequency and Phase Offset]] |

| − | [[Aufgaben:Aufgabe_2.4Z:_Tiefpass-Einfluss_bei_Synchrondemodulation| | + | [[Aufgaben:Aufgabe_2.4Z:_Tiefpass-Einfluss_bei_Synchrondemodulation|Exercise 2.4Z: Low-pass influence with Synchronous Demodulation]] |

| − | [[Aufgaben:Aufgabe_2.5:_ZSB–AM_über_einen_Gaußkanal| | + | [[Aufgaben:Aufgabe_2.5:_ZSB–AM_über_einen_Gaußkanal|Exercise 2.5: DSB-AM via a Gaussian Channel]] |

| − | [[Aufgaben:Aufgabe_2.5Z:_Nochmals_Verzerrungen_bei_ZSB-AM| | + | [[Aufgaben:Aufgabe_2.5Z:_Nochmals_Verzerrungen_bei_ZSB-AM|Exercise 2.5Z: Distortions with DSB-AM]] |

| − | [[Aufgaben:Aufgabe_2.6:_Freiraumdämpfung| | + | [[Aufgaben:Aufgabe_2.6:_Freiraumdämpfung|Exercise 2.6: Free Space Attenuation]] |

| − | [[Aufgaben:Aufgabe_2.6Z:_Signal-to-Noise-Ratio_(SNR)| | + | [[Aufgaben:Aufgabe_2.6Z:_Signal-to-Noise-Ratio_(SNR)|Exercise 2.6Z: Signal-to-Noise-Ratio (SNR)]] |

{{Display}} | {{Display}} | ||

Revision as of 22:31, 29 November 2021

Contents

- 1 Block diagram and time domain representation

- 2 Description in the frequency domain

- 3 Prerequisites for the application of a synchronous demodulator

- 4 Influence of a frequency offset

- 5 Influence of a phase offset

- 6 Influence of linear channel distortions

- 7 Influence of noise interference

- 8 Calculating noise power

- 9 Relationship between $P_q$ and $P_{\rm S}$

- 10 Sink SNR and the performance parameter

- 11 Exercises for the Chapter

Block diagram and time domain representation

Modulation at the transmitter only makes sense, if it is possible to reverse this signal conversion at the receiver end, ideally without loss of information. In any form of amplitude modulation - be it double sideband (DSB) or single sideband (SSB), with or without a carrier signal - the so-called synchronous demodulator fulfils this task.

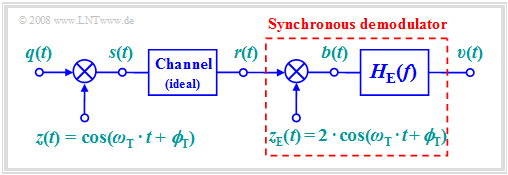

The following should be noted with regard to the above block diagram:

- For modulation, we will focus on "DSB–AM without a carrier" $($modulation depth $m → ∞)$ . However, synchronous demodulation is also applicable in "DSB–AM with carrier".

- Let the channel be ideal and the distortions negligible, that the received signal $r(t)$ is identical to the transmitted signal $s(t)$ :

- $$r(t) = s(t) = q(t) \cdot \cos(\omega_{\rm T} \cdot t + \phi_{\rm T})\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- At the receiver, $r(t)$ is first multiplied by the receiver-side carrier $z_{\rm E}(t)$ , which is identical to the transmitter-side carrier $z(t)$ but larger by a factor of $2$ :

- $$z_{\rm E}(t) = 2 \cdot \cos(\omega_{\rm T} \cdot t + \phi_{\rm T})\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- DThe result of the multiplication is the signal $b(t)$. . Considering the trigonometric transformation $\cos^2(α) = 1/2 · \big [1 + \cos(2α)\big ]$ we get

- $$b(t) = r(t) \cdot z_{\rm E}(t) = 2 \cdot q(t) \cdot \cos^2(\omega_{\rm T} \cdot t + \phi_{\rm T}) = q(t) + q(t) \cdot \cos(2 \cdot \omega_{\rm T} \cdot t + 2\cdot \phi_{\rm T})\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- The second term is in the range around twice the carrier frequency. If the signal bandwidth is $B_{\rm NF} < f_{\rm T}$, which is always true in practice, this component can be suppressed by a low-pass filter $H_{\rm E}(f)$ with suitable dimensions, and we obtain $v(t) = q(t)$.

Description in the frequency domain

Assuming an even source signal $q(t)$ ⇒ with a real spectrum $Q(f)$ and a sinusoidal carrier $z(t)$ , the imaginary transmitted spectrum $S(f)$ is obtained according to the second plot, where $A_{\rm T} ≠ 0$ also takes into account the DSB-AM with a carrier (shown by the red Dirac function). Because the channel is ideal, $R(f) = S(f)$.

The operation of the synchronous demodulator can be explained in the frequency domain as follows:

- The receiver-side carrier signal $z_{\rm E}(t) = 2 · z(t) = 2 · \sin(ω_{\rm T} · t)$ leads to two Dirac functions in the spectral domain at $\pm f_{\rm T}$ with weights $\pm \rm j$. The negative imaginary part occurs at $f = +f_{\rm T}$ .

- The multiplication $b(t) = r(t) · z_{\rm E}(t)$ corresponds to the convolution of the associated spectral functions:

- $$B(f) = R(f) \star Z_{\rm E}(f)\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- Convolution of the Dirac function $ - {\rm j} \cdot δ(f – f_{\rm T})$ with the wholly imaginary spectrum $R(f)$ leads to completely real spectral components around $f = 0$ and $f = 2f_{\rm T}$. These components are marked with a "+" on the graph.

- The second convolution product ${\rm j} · δ(f + f_{\rm T}) \star R(f)$ yields a low-frequency spectral component around $f = 0$. in addition to a component at $–2f_{\rm T}$ . These spectral components are marked with "–".

- The spectrum after the low-pass $H_{\rm E}(f)$ is $V(f) = Q(f) + A_{\rm T} · δ(f)$. For DSB-AM with a carrier, the interfering DC component can be removed by a band limit on the low end, i.e. $H_{\rm E}(f = 0) = 0$.

- The color assignment in the diagram (USB blue, LSB green, carrier red) shows that the synchronous demodulator uses both the USB and the LSB for signal reconstruction.

Prerequisites for the application of a synchronous demodulator

The output signal $v(t)$ is identical to the source signal $q(t)$ if the following conditions are satisfied:

- The bandwidth $B_{\rm NF}$ of the source signal is smaller than the carrier frequency $f_{\rm T}$. This restriction is not particularly drastic and is not relevant for practical applications.

- The carrier frequencies of the transmitter and receiver are exactly matched. This requires carrier recovery at the receiver and thus involves some "cost".

- There is also perfect phase synchrony between the the carrier signals $z(t)$ and $z_{\rm E}(t)$ at the transmitter and receiver end, respectively.

- The channel frequency response $H_{\rm K}(f)$ is ideally equal to $1$. in the passband $f_{\rm T} - B_{\rm NF} ≤ |f| ≤ f_{\rm T} + B_{\rm NF}$ . Frequency-independent attenuation or frequency-linear phase (delay) are usually tolerated.

- The influence of noise and external disturbances is assumed to be negligible in this model. However, even with non-negligible noise, the synchronous demodulator is superior to other demodulators.

- The receiver filter $H_{\rm E}(f)$ (subscript E stands for German "Empfangsfilter" ⇒ receiver filter) is equal to "one" for $|f| ≤ B_{\rm NF}$ and equal to "zero" for $|f| ≥ 2f_{\rm T} - B_{\rm NF}$. The process in between is not relevant (see graph in the previous section).

- BFor the modulation method "DSB-AM with carrier", $H_{\rm E}(f = 0) ≡ 0$ must additionally ensure that the carrier added at the transmitter is no longer included in the sink signal.

The following sections describe the effects if some of the above conditions are not met.

Influence of a frequency offset

As the name "synchronous demodulator” it only works when there is complete synchrony between the carrier signals of the transmitter and receiver. On the other hand, if the carrier frequencies differ by a frequency offset $Δ\hspace{-0.05cm}f_{\rm T}$, for example

- $$\begin{align*}z(t) & = 1 \cdot \cos(2 \pi f_{\rm T} \cdot t + \phi_{\rm T})\hspace{0.05cm}, \\ z_{\rm E}(t) & = 2 \cdot \cos(2 \pi (f_{\rm T} + \Delta\hspace{-0.05cm} f_{\rm T}) \cdot t + \phi_{\rm T})\hspace{0.05cm},\end{align*}$$

then for the sink signal spectrum we obtain:

- $$V(f) = {1}/{2}\cdot Q(f + \Delta \hspace{-0.05cm}f_{\rm T}) + {1}/{2}\cdot Q(f - \Delta\hspace{-0.05cm} f_{\rm T}) = Q(f) \star \big[ {1}/{2}\cdot \delta(f + \Delta\hspace{-0.05cm} f_{\rm T}) + {1}/{2}\cdot \delta (f - \Delta \hspace{-0.05cm}f_{\rm T}) \big] \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

This result can be verified in the frequency domain using the sketch on the Description page. After transforming the equation to the time domain, we get:

- $$v(t) = q(t) \cdot \cos(2 \pi \cdot \Delta \hspace{-0.05cm}f_{\rm T} \cdot t )\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

$\text{Conclusion:}$ for DSB-AM (with or without carrier), synchronous demodulation with frequency offset $ \Delta \hspace{-0.05cm}f_{\rm T}$ leads to attenuation distortions, characterized by the time-dependent factor $\cos(2 \pi \cdot \Delta \hspace{-0.05cm}f_{\rm T} \cdot t )$.

The frequency offset $Δ\hspace{-0.05cm}f_{\rm T}$, which is due to inaccuracies in the realization of carrier recovery, is usually very small and ranges from a few Hertz to about $100\text{ Hz}$ . In this context, one usually speaks of a "beat".

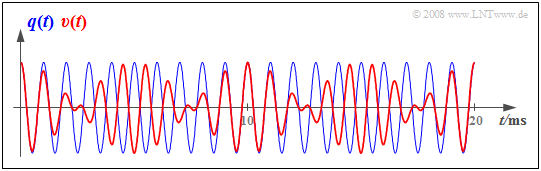

$\text{Example 1:}$ The graph shows

- a cosine-shaped source signal with frequency $f_{\rm N} = 1\ \rm kHz$

⇒ blue oscillation, and - the sink signal obtained with a synchronous demodulator $v(t)$

⇒ red curve.

Here, a frequency offset of $Δ\hspace{-0.05cm}f_{\rm T} = 100\ \rm Hz$ was used as a basis. This results in:

- $$\begin{align*}v(t ) & = 1\,{\rm V} \cdot \cos (2 \pi \cdot 1\,{\rm kHz} \cdot t) \cdot \cos (2 \pi \cdot 0.1\,{\rm kHz} \cdot t) =\\ &= 0.5\,{\rm V} \cdot \cos (2 \pi \cdot 0.9\,{\rm kHz} \cdot t) + 0.5\,{\rm V} \cdot \cos (2 \pi \cdot 1.1\,{\rm kHz} \cdot t) \hspace{0.05cm}.\end{align*}$$

From a spectral point of view, the $1\ \rm kHz$ oscillation becomes two superimposed oscillations with frequencies $0.9\ \rm kHz$ and $1.1\ \rm kHz$ with half the amplitude.

- New frequencies occur as a result – i.e., nonlinear distortions.

- In contrast, the transmitted frequency $(1\ \rm kHz)$ is no longer included in $v(t)$ .

Influence of a phase offset

Now, for the transmitter-side and receiver-side carrier signal, it holds that:

- $$\begin{align*}z(t) & = 1 \cdot \cos(2 \pi f_{\rm T} t + \phi_{\rm T})\hspace{0.05cm}, \\ z_{\rm E}(t) & = 2 \cdot \cos(2 \pi f_{\rm T} t + \phi_{\rm E})\hspace{0.05cm}.\end{align*}$$

This gives Δ𝛟T=𝛟E-𝛟T For the signal immediately after multiplication by the phase offset $Δ \mathbf{ϕ_{\rm T} = ϕ_{\rm E} - ϕ_{\rm T} }$, this gives:

- $$b(t) = q(t) \cdot \cos(\omega_{\rm T} \cdot t + \phi_{\rm T}) \cdot 2 \cdot \cos(\omega_{\rm T} \cdot t + \phi_{\rm E})= q(t)\cdot \cos(\Delta \phi_{\rm T}) + q(t) \cdot \cos(2 \cdot \omega_{\rm T} \cdot t + \phi_{\rm E}+ \phi_{\rm T})\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

Thus, taking into account the low-pass filter, the result for the sink signal is:

- $$v(t) = q(t)\cdot \cos(\Delta \phi_{\rm T}) \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

$\text{Conclusion:}$ for DSB-AM (with or without carrier), synchronous demodulation with phase offset $Δ\mathbf{ϕ_{\rm T} }$ does not lead to distortions, but only to a frequency independent attenuation by the time independent factor $\cos(Δ\mathbf{ϕ_{\rm T} })$.

The reason for this less serious signal change than in the case of a frequency offset is that in this case the time $t$ is missing in the argument of the cosine function.

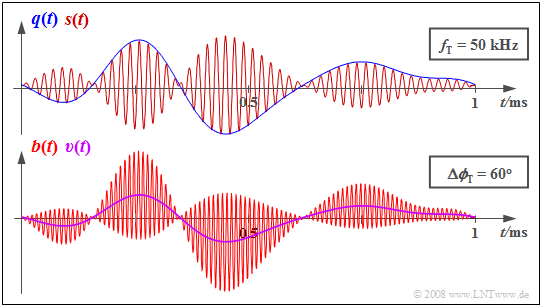

$\text{Example 2:}$ The diagram shows the signals $q(t)$ and $s(t)$ at the transmitter above, and the receiver-side signals $b(t)$ and $v(t)$ below.

- Due to the phase offset of $Δ \mathbf{ϕ_{\rm T} } = π/3\ (60^\circ)$ , the sink signal $v(t)$ is only half the size of the source signal $q(t)$.

- However, the waveform of $q(t)$ is preserved in $v(t)$ .

Influence of linear channel distortions

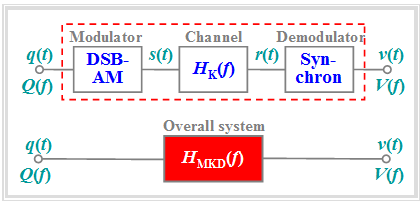

In the section Attenuation distortions of the book "Linear and Time Invariant Systems" it was already suggested that the entire communication system - consisting of modulator, channel, and demodulator – consisting of Modulator, Channel (or K for "Kanal" in German)and Demodulator – can be completely described by the resulting frequency response $H_{\rm MKD}(f)$ if

- either the system is free of distortion, or

- only linear distortions arise with respect to the $q(t)$ and $v(t)$ signals.

In contrast, nonlinear distortions are not captured by this diagram because the multiplicative relationship $V(f) = Q(f)\cdot H_{\rm MKD}(f)$ does not allow for the emergence of new frequencies. If $Q(f_0) = 0$, then $V(f_0) = 0$ will always hold as well.

The above conditions are fulfilled for the following system variant:

- The modulator generates a DSB-AM (with or without carrier) around the carrier frequencyThe channel is describable by the frequency response $H_{\rm K}(f)$ with bandpass characteristics and its bandwidth is sufficient.

- The synchronous demodulator is synchronous in frequency and phase and the filter $H_{\rm E}(f)$ is ideal (rectangular).

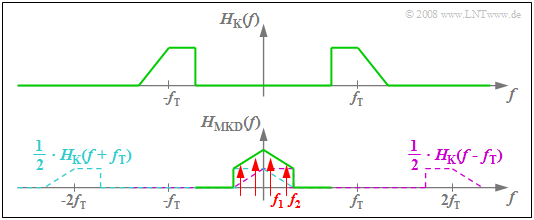

$\text{Definition:}$ Thus, the resulting frequency response of the modulator-channel-demodulator is:

- $$H_{\rm MKD}(f) = {1}/{2} \cdot \big[ H_{\rm K}(f + f_{\rm T}) + H_{\rm K}(f - f_{\rm T})\big] \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- If $\vert H_{\rm MKD}(f) \vert $ is not constant in the range of the signal bandwidth, the different spectral components of the source signal $q(t)$ are also transmitted differently ⇒ attenuation distortions.

- Similarly, phase distortions may occur if the phase function arc $\text{arc} \ H_{\rm MKD}(f) $ is nonlinear in $f$ .

$\text{Example 3:}$ The diagram illustrates the above calculation rule for the resulting system function..

- From the asymmetric bandpass $H_{\rm K}(f)$ – – related to the carrier frequency $f_{\rm T}$ – becomes the symmetric function $H_{\rm MKD}(f)$ in the AF range (around $($um $f = 0)$ ).

- If the source signal consists of two frequency components – indicated in the graph by the red marker arrows – the spectral line at $f_2$ is more attenuated than the frequency $f_1$

⇒linear attenuation distortions arise.

- The fact that $H_{\rm MKD}(f)$ also includes components around $±2f_{\rm T}$ is not a major concern. These do not affect low-pass considerations.

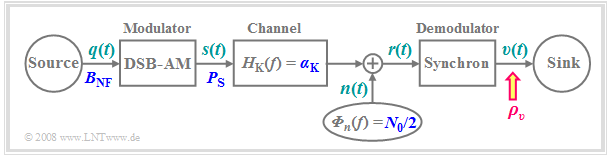

Influence of noise interference

Now we wish to clarify the extent to which the transmission quality is affected by a stochastic interference or noise signal $n(t)$ . We will be assuming the following scenario, which has already been presented on the Investigations at the AWGN channel page.

In particular, we make the following assumptions:

- Only double-sideband amplitude modulation with modulation depth $m$ and an ideal synchronous demodulator without phase and frequency offsets are considered.

- According to the extended AWGN channel model, where $α_{\rm K}$ is a frequency-independent transmission factor and the interference signal $n(t)$ models white noise with two-sided noise power density $N_0/2$ , the following holds for the received signal:

- $$r(t) = \alpha_{\rm K} \cdot s(t) + n(t) \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- Representing a source signal $q(t)$ of bandwidth $B_{\rm NF}$ , a cosine-shaped message signal of frequency $B_{\rm NF}$ is assumed here:

- $$q(t) = A_{\rm N} \cdot \cos(2 \pi \cdot B_{\rm NF} \cdot t ) \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

With these assumptions, the sink signal is $v(t) = \alpha_{\rm K} \cdot q(t) + \varepsilon(t) \hspace{0.05cm}$, where the cause of the stochastic component $ε(t)$ is the bandpass noise $n(t)$ at the input of the synchronous demodulator.

$\text{Definition:}$ the signal-to-noise power ratio at the sink is used as a quantitative measure of transmission quality, and is expressed here in powers of $q(t)$ and $ε(t)$ :

- $$\rho_v = \frac{\alpha_{\rm K}^2 \cdot P_q}{P_\varepsilon} \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

In the following, we will refer to this ratio as the sink SNR $ρ_v$ and the logarithmic representation $10 · \lg ρ_v$ as the sink-to-noise ratio in dB.

Calculating noise power

We first calculate the power $P_ε$ of the error signal $ε(t)$, which we refer to as the "noise power" for simplicity. The error signal $ε(t)$ is obtained from the noise signal $n(t)$ at the input by

- Multiplying by $z_{\rm E}(t) = 2 · \cos(ω_{\rm T} · t + \mathbf{ϕ_{\rm T} })$ and

- a subsequent (ideal) low-pass filtering to the frequency range $\pm B_{\rm NF}$.

For the power density spectrum ${\it Φ_ε}'(f)$ without considering the low-pass filter, with ${\it Φ}_n(f) = N_0/2$, it holds that:

- $${\it \Phi}_\varepsilon \hspace{-0.10cm} '(f) = {\it \Phi}_n (f) \star {\it \Phi}_{z {\rm E}}(f) \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

In the books "Signal Representation and „Theory of Stochastic Signals”, it was shown that the spectrum and the power density spectrum of a cosine signal $x(t) = A · \cos(2πf_{\rm T}t)$ are given by:

- $$X(f) = \frac{A}{2}\cdot \delta(f + f_{\rm T}) + \frac{A}{2}\cdot \delta(f - f_{\rm T}) \hspace{0.05cm}, $$

- $$ {\it \Phi}_x (f) = \frac{A^2}{4}\cdot \delta(f + f_{\rm T}) + \frac{A^2}{4}\cdot \delta(f - f_{\rm T}) \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

Applied to the receive-side carrier signal $z_{\rm E}(t)$ , with $A = 2$, the second equation is

- $${\it \Phi}_{z {\rm E}}(f)= \delta(f + f_{\rm T}) + \delta(f - f_{\rm T}) \hspace{0.05cm}$$

and this is independent of phase (since all phase relationships are lost in the power density spectrum).

Considering that ${\it Φ}_n(f)$ is constant for all frequencies ⇒ "white noise" , we get:

- $${\it \Phi}_\varepsilon \hspace{-0.10cm} '(f) = {\it \Phi}_n (f + f_{\rm T}) + {\it \Phi}_n (f - f_{\rm T}) = 2 {\it \Phi}_n (f) = N_0 \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

The power density spectrum (PDS) after the low-pass filter is exactly as large for $|f| < B_{\rm NF}$ and zero beyond this range.

- $${\it \Phi}_\varepsilon (f) = \left\{ \begin{array}{c} N_0 \\ 0 \\ \end{array} \right.\quad \begin{array}{*{10}c} {\rm{for}}\\ \\ \end{array}\begin{array}{*{20}c} |f|< B_{\rm NF} \hspace{0.05cm}, \\ {\rm otherwise} \hspace{0.05cm}. \\ \end{array}$$

By integration, we obtain the power $P_ε = 2N_0 · B_{\rm NF}$. . Thus, with this intermediate result, the sinking SNR can be given as:

- $$\rho_v = \frac{\alpha_{\rm K}^2 \cdot P_q}{P_\varepsilon} = \frac{\alpha_{\rm K}^2 \cdot P_q}{N_0 \cdot B_{\rm NF}} \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

In the next section, we still establish the relationship between the power 𝑃𝑞 of the source signal and the transmit power $P_q$ .

Relationship between $P_q$ and $P_{\rm S}$

To characterise the relationship between the sink–SNR $\rho_v$ and the transmission power $P_{\rm S}$ , we first need the relationships between

- source signal $q(t)$ ⇒ power $P_q$, and

- transmitted signal $s(t)$ ⇒ transmission power $P_{\rm S}$.

$\text{Anticipated result:}$ In the case of "DSB–AM with carrier" the following holds true for a modulation depth $m$,:

- $$P_{\rm S} = { P_q}/{2} \cdot \hspace{0.05cm} \left( 1 + {2}/{m^2}\right)\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- Note that this equation is only applicable when $q(t)$ describes a harmonic oscillation.

- The "DSB-AM without carrier" is included in the equation as a special case for 𝑚→∞.

$\text{Proof:}$ Cosine oscillations are assumed in each case, i.e. the following equations:

- $$q(t) = A_{\rm N} \cdot \cos(\omega_{\rm N} \cdot t ) \hspace{0.05cm},$$

- $$s(t) = \big[ q(t) + A_{\rm T}\big] \cdot \cos(\omega_{\rm T} \cdot t ) = A_{\rm T} \cdot \cos(\omega_{\rm T} \cdot t ) + {A_{\rm N} }/{2}\cdot \cos\big [(\omega_{\rm T}+ \omega_{\rm N}) \cdot t \big] + {A_{\rm N} }/{2}\cdot \cos\big[(\omega_{\rm T}- \omega_{\rm N}) \cdot t \big]\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- The power of the source signal, in relation to a resistance of $1 \ \rm Ω$, with the period $T_{\rm N}$, is:

- $$P_{q} = \frac{1}{T_{\rm N} }\cdot\int_{0}^{ T_{\rm N} } {q^2(t)}\hspace{0.1cm}{\rm d}t = \frac{A_{\rm N}^2}{T_{\rm N} }\cdot\int_{0}^{T_{\rm N} } {\cos^2(2 \pi\cdot{t}/{T_{\rm N} })}\hspace{0.1cm}{\rm d}t = \frac{A_{\rm N}^2}{2}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- Accordingly, for the power of the transmitted signal, one obtains :

- $$P_{\rm S} = \frac{A_{\rm T}^2}{2} + \frac{(A_{\rm N}/2)^2}{2} + \frac{(A_{\rm N}/2)^2}{2} = \frac{A_{\rm T}^2}{2} + \frac{A_{\rm N}^2}{4} \hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} P_{\rm S} = {1}/{2} \cdot \left( P_q + A_{\rm T}^2 \right) \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- This equation is valid for both DSB-AM without carrier $(A_{\rm T} = 0)$ and DSB-AM with carrier. Since $q(t)$ was assumed to be a harmonic oscillation, given a modulation depth $m = A_{\rm N}/A_{\rm T}$ this can also be written as:

- $$P_{\rm S} = {A_{\rm N}^2}/{4} \cdot \left( 1 +{2A_{\rm T}^2}/{A_{\rm N}^2} \right)= P_q/2 \cdot \left( 1 +{2}/{m^2} \right)\hspace{0.05cm}.\hspace{5.4cm}{\rm q.e.d.}$$

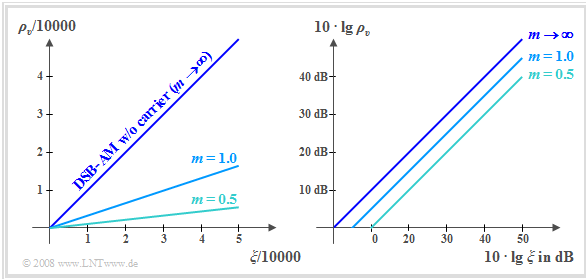

Sink SNR and the performance parameter

With the results of the last three sections, the sink SNR of DSB-AM can be written as:

- $$\rho_v = \frac{\alpha_{\rm K}^2 \cdot P_q}{P_\varepsilon} = \frac{\alpha_{\rm K}^2 \cdot P_{\rm S} }{N_0 \cdot B_{\rm NF} } \cdot \frac{1}{1 + {2}/{m^2} } \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

The following is a detailed discussion of this equation. Already in the chapter Investigations at the AWGN channel it was justified why it makes sense to state the sink SNR $ρ_v$ as a function of the performance parameter $ξ$ named below:

- $$\xi = \frac{\alpha_{\rm K}^2 \cdot P_{\rm S}}{N_0 \cdot B_{\rm NF}} \hspace{0.5cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.5cm} \rho_v = \frac{\xi}{1 + {2}/{m^2}} \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

The two graphs show the corresponding curves - linear on the left and double-logarithmic on the right.

The curves are to be interpreted as follows:

- For the system variant „DSB–AM without a carrier” with $m → ∞$ the above equation yields the simple relationship $ρ_v = ξ$. This gives the bisector of the angle for both the linear and double logarithmic plots.

- A greater transmission power $P_{\rm S}$ leads to a better sink SNR, as does a larger transmission factor $α_{\rm K}$ (⇒ lower attenuation).However, $10 · \lg ρ_v$ is also increased by a smaller noise power density $N_0$ and a smaller bandwidth $B_{\rm NF}$ , other things being equal.

- For "DSB–AM with carrier” with a modulation depth $m$:

- $$\rho_v = \xi \cdot \frac{1}{1 + {2}/{m^2}}\hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} 10 \cdot {\rm lg }\hspace{0.1cm}\rho_v = 10 \cdot {\rm lg }\hspace{0.1cm}\xi - 10 \cdot {\rm lg }\hspace{0.1cm} \left({1 + {2}/{m^2}}\right)\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- In the double logarithmic representation (see right graph), this leads to a downward parallel shift of the curves, for example at $m = 1$ by $4.77$ dB  and at $m = 0.5$ by $9.54$ dB.

- All statements are valid under the assumption of an ideal synchronous demodulator. In this case, the "DSB-AM with carrier" method actually makes no sense. The added carrier would only lead to an unnecessarily large transmit power and could not be used for demodulation.

- The curves are valid for perfect frequency and phase synchronization. However, in order to be able to determine the parameters 𝑓 $f_{\rm T}$ and $\mathbf{ϕ_{\rm T} }$ from the received signal $r(t)$ with less effort, a small carrier component in the transmitted signal makes sense.

- When $m = 3$ , it is only an insignifican deterioration of less than one dB compared to "DSB-AM without carrier".

Exercises for the Chapter

Exercise 2.4: Frequency and Phase Offset

Exercise 2.4Z: Low-pass influence with Synchronous Demodulation

Exercise 2.5: DSB-AM via a Gaussian Channel

Exercise 2.5Z: Distortions with DSB-AM

Exercise 2.6: Free Space Attenuation

Exercise 2.6Z: Signal-to-Noise-Ratio (SNR)