Contents

- 1 Generalized system functions of time variant systems

- 2 Simplifications due to the GWSSUS requirements

- 3 Autocorrelation function of the time variant impulse response

- 4 Power density spectrum of the time variant impulse response

- 5 ACF and PDS of the frequency-variant transfer function

- 6 ACF and PDS of the delay Doppler function

- 7 ACF and PDS of the time variant transfer function

- 8 Parameters of the GWSSUS model

- 9 Simulation according to the GWSSUS model

- 10 Exercises to the chapter

- 11 List of sources

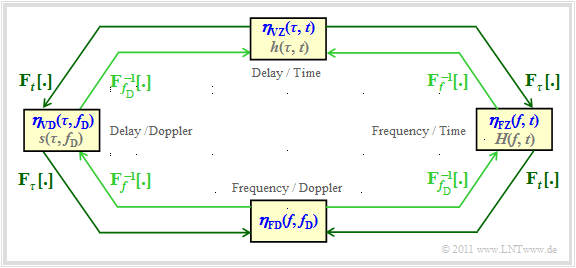

Generalized system functions of time variant systems

Linear time-invariant systems $\rm (LTI)$ can be completely described with only two system functions,

- the transfer function $H(f)$ and

- the impulse response $h(t)$ – after renaming $h(\tau)$.

In contrast, four different functions are possible with time-variant systems $\rm (LTV)$ . A formal distinction of these functions with regard to time and frequency domain representation by lowercase and uppercase letters is thus excluded.

Therefore a nomenclature change will be made, which can be formalized as follows:

- The four possible system functions are uniformly denoted by $\boldsymbol{\eta}_{12}$ .

- The first subindex is either a $\boldsymbol{\rm V}$ $($because of German $\rm V\hspace{-0.05cm}$erzögerung ⇒ delay time $\tau)$ or a $\boldsymbol{\rm F}$ $($frequency $f)$.

- Either a $\boldsymbol{\rm Z}$ $($because of German $\rm Z\hspace{-0.05cm}$eit ⇒ time $t)$ or a $\boldsymbol{\rm D}$ $($Doppler frequency $f_{\rm D})$ is possible as the second subindex.

Since, in contrast to line-based transmission, the system functions of mobile communications cannot be described deterministically, but are statistical variables, the corresponding correlation functions must be considered later on. In the following, we will refer to these as $\boldsymbol{\varphi}_{12}$, and use the same indices as for the system functions $\boldsymbol{\eta}_{12}$.

- These formalized designations are inscribed in the graphic in blue letters.

- Additionally, the designations used in other chapters or literature are given (grey letters). In the other chapters these are also partly used.

${\rm (1)}$ At the top you can see the time variant impulse response ${\eta}_{\rm VZ}(\tau,\hspace{0.05cm} t) \equiv h(\tau,\hspace{0.05cm} t)$ in the delay–time range. The associated autocorrelation function $\rm (ACF)$ is

- \[\varphi_{\rm VZ}(\tau_1, t_1, \tau_2, t_2) = {\rm E} \big[ \eta_{\rm VZ}(\tau_1,\hspace{0.05cm} t_1) \cdot \eta_{\rm VZ}^{\star}(\tau_2, t_2) \big]\hspace{0.05cm}. \]

${\rm (2)}$ For the frequency–time representation you get the time-variant transfer function ${\eta}_{\rm FZ}(f,\hspace{0.05cm} t) \equiv H(f,\hspace{0.05cm} t)$.

The Fourier transform with respect to $\tau$ is represented in the graph by ${\rm F}_\tau\hspace{0.05cm}[ \cdot ]$ . The Fourier integral is written out in full:

- \[\eta_{\rm FZ}(f, \hspace{0.05cm} t) = \int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} \eta_{\rm VZ}(\tau,\hspace{0.05cm} t) \cdot {\rm e}^{- {\rm j}\cdot 2 \pi f \tau}\hspace{0.15cm}{\rm d}\tau \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.3cm} \text{kurz:} \hspace{0.2cm} \eta_{\rm FZ}(f, t) \hspace{0.2cm} \stackrel{f, \hspace{0.05cm} \tau}{\bullet\!\!-\!\!\!-\!\!\!-\!\!\circ} \hspace{0.2cm} \eta_{\rm VZ}(\tau, t) \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

- The ACF of this time variant transfer function is general:

- \[\varphi_{\rm FZ}(f_1, t_1, f_2, t_2) = {\rm E} \big [ \eta_{\rm FZ}(f_1, t_1) \cdot \eta_{\rm FZ}^{\star}(f_2, t_2) \big ]\hspace{0.05cm}.\]

${\rm (3)}$ The Scatter–Function ${\eta}_{\rm VD}(\tau,\hspace{0.05cm} f_{\rm D}) \equiv s(\tau,\hspace{0.05cm} f_{\rm D})$ corresponding to the left block describes the mobile communications channel in the Delay–Doppler Area.

$f_{\rm D}$ describes the Doppler frequency. The scatter function results from ${\eta}_{\rm VZ}(\tau,\hspace{0.05cm} t)$ through Fourier transformation with respect to the second parameter $t$:

- \[ \eta_{\rm VD}(\tau, f_{\rm D}) \hspace{0.2cm} \stackrel{f_{\rm D}, \hspace{0.05cm}t}{\bullet\!\!-\!\!\!-\!\!\!-\!\!\circ} \hspace{0.2cm} \eta_{\rm VZ}(\tau, t)\hspace{0.3cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} \varphi_{\rm VD}(\tau_1, f_{\rm D_1}, \tau_2, f_{\rm D_2}) = {\rm E} \left [ \eta_{\rm VD}(\tau_1, f_{\rm D_1}) \cdot \eta_{\rm VD}^{\star}(\tau_2, f_{\rm D_2}) \right ] \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

${\rm (4)}$ Finally, we consider the so-called frequency-variant transfer function $\eta_{\rm FD}(f, f_{\rm D})$, i.e. the frequency–Doppler representation.

According to the graph, this can be reached in two ways:

- $$\eta_{\rm FD}(f, f_{\rm D}) \hspace{0.2cm} \stackrel{f_{\rm D}, \hspace{0.05cm}t}{\bullet\!\!-\!\!\!-\!\!\!-\!\!\circ} \hspace{0.2cm} \eta_{\rm FZ}(f, t)\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.5cm}\eta_{\rm FD}(f, f_{\rm D}) \hspace{0.2cm} \stackrel{f, \hspace{0.05cm}\tau}{\bullet\!\!-\!\!\!-\!\!\!-\!\!\circ} \hspace{0.2cm} \eta_{\rm VD}(\tau, f_{\rm D})\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

$\text{Hints:}$

- The specified Fourier correlations between the system functions in the graph are illustrated by the outer, dark green arrows and are marked with ${\rm F}_p\hspace{0.05cm}[\hspace{0.05cm} \cdot \hspace{0.05cm}]$ ,

the index $p$ indicates to which parameter $\tau$, $f$, $t$ or $f_{\rm D}$ does the Fourier transformation refer. - The inner (lighter) arrows indicate the links via the inverse Fourier transform. For this we use the notation ${ {\rm F}_p}^{-1}\hspace{0.05cm}[ \hspace{0.05cm} \cdot \hspace{0.05cm} ]$.

- The applet Impulses and Spectra illustrates the connection between the time and frequency domain, which can be described by formulas using Fourier transformation and Fourier inverse transformation.

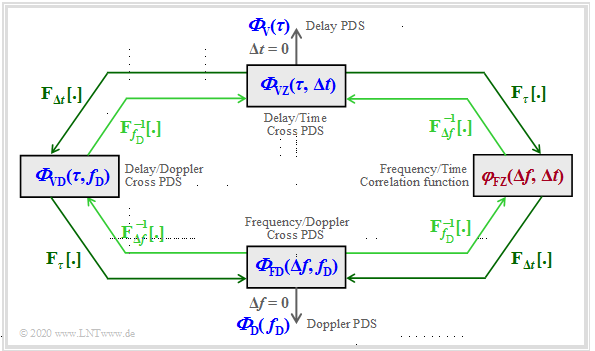

Simplifications due to the GWSSUS requirements

The general relationship between the four system functions is very complicated due to non-stationary effects.

Compared to the general model, some limitations have to be made in order to arrive at a suitable model for the mobile communications channel from which relevant statements for practical applications can be derived.

The following definitions lead to the $\rm GWSSUS$ model

$( \rm G$aussian $\rm W$ide $\rm S$ense $\rm S$tationary $\rm U$ncorrelated $\rm S$cattering$)$:

- The random process of the channel impulse response $h(\tau,\hspace{0.1cm} t) = {\eta}_{\rm VZ}(\tau,\hspace{0.1cm} t)$ is generally assumed to be complex (i.e., description in the equivalent low-pass range), Gaussian $($identifier $\rm G)$ and zero-mean (Rayleigh, not Rice, that means, no line of sight) .

- The random process is weakly stationary ⇒ its characteristics change only slightly with time, and the ACF $ {\varphi}_{\rm VZ}(\tau_1,\hspace{0.05cm} t_1,\hspace{0.05cm}\tau_2,\hspace{0.05cm} t_2)$ of the time variant impulse response does not depend on the absolute times $t_1$ and $t_2$ but only on the time difference $\Delta t = t_2 - t_1$. This is indicated by the identifier $\rm WSS$ ⇒ $\rm W$ide $\rm S$ense $\rm S$tationary.

- The individual echoes due to multipath propagation are uncorrelated, which is expressed by the identifier $\rm US$ ⇒ $\rm U$ncorrelated $\rm S$cattering.

The mobile communications channel can be described in full according to this graph. The individual power density spectra (labeled blue) and the correlation function (labeled red) is explained in detail in the following pages.

Autocorrelation function of the time variant impulse response

We now consider the autocorrelation function $\rm (ACF)$ of the time variant impulse response ⇒ $h(\tau,\hspace{0.1cm} t) = {\eta}_{\rm VZ}(\tau,\hspace{0.1cm} t)$ more closely. It shows:

- Based on the $\rm WSS$ property, the autocorrelation function can be written with $\Delta t = t_2 - t_1$ :

- \[\varphi_{\rm VZ}(\tau_1, t_1, \tau_2, t_2) = \varphi_{\rm VZ}(\tau_1, \tau_2, \Delta t)\hspace{0.05cm}.\]

- Since the echoes were assumed to be independent of each other $\rm (US$ property$)$, the impulse response can be assumed to be uncorrelated with respect to the delays $\tau_1$ and $\tau_2$. Then:

- \[\varphi_{\rm VZ}(\tau_1, \tau_2, \Delta t) = 0 \hspace{0.35cm}{\rm f\ddot{u}r}\hspace{0.35cm} \tau_1 \ne \tau_2\hspace{0.05cm}. \]

- If one now replaces $\tau_1$ with $\tau$ and $\tau_2$ with $\tau + \Delta \tau$, this autocorrelation function can be represented in the following way:

- \[\varphi_{\rm VZ}(\Delta \tau, \Delta t) = \delta(\Delta \tau) \cdot {\it \Phi}_{\rm VZ}(\tau, \Delta t) \hspace{0.05cm}. \]

- Because of the convolution property of the Dirac function, the ACF for $\tau_1 \ne \tau_2$ ⇒ $\Delta \tau \ne 0$ disappears.

- $ {\it \Phi}_{\rm VZ}(\tau, \Delta t) \hspace{0.1cm}$ is the delay–time's cross power density spectrum, which depends on the delay $\tau \ (= \tau_1 =\tau_2)$ and on the time difference $\Delta t = t_2 - t_1$ .

$\text{Please note:}$

- With this approach, the autocorrelation function $\varphi_{\rm VZ}(\Delta \tau, \Delta t)$ and the power density spectrum ${\it \Phi}_{\rm VZ}(\tau, \Delta t) $ are not connected via the Fourier transform as usual, but are linked via a Dirac function:

- \[\varphi_{\rm VZ}(\Delta \tau, \Delta t) = \delta(\Delta \tau) \cdot {\it \Phi}_{\rm VZ}(\tau, \Delta t) \hspace{0.05cm}. \]

- Not all symmetry properties that follow from the Wiener–Khintchine theorem are thus given here. In particular it is quite possible and even very likely that such a power density spectrum is an odd function.

In the overview on the last page, the delay–time's cross power density spectrum ${\it \Phi}_{\rm VZ}(\tau, \Delta t) $ can be seen in the top middle.

- Since $\eta_{\rm VZ}(\tau, t) $, like any impulse response, has the unit $\rm [1/s]$ , the autocorrelation function has the unit $\rm [1/s^2]$:

- \[\varphi_{\rm VZ}(\Delta \tau, \Delta t) = {\rm E} \left [ \eta_{\rm VZ}(\tau, t) \cdot \eta_{\rm VZ}^{\star}(\tau + \Delta \tau, t + \Delta t) \right ].\]

- But since the Dirac function with the time argument $\delta(\Delta \tau)$ also has the unit $\rm [1/s]$ the delay–time's cross power density spectrum ${\it \Phi}_{\rm VZ}(\tau, \Delta t) $ also has the unit $\rm [1/s]$:

- \[\varphi_{\rm VZ}(\Delta \tau, \Delta t) = \delta(\Delta \tau) \cdot {\it \Phi}_{\rm VZ}(\tau, \Delta t) \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

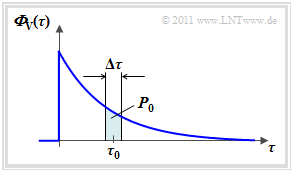

Power density spectrum of the time variant impulse response

One obtains the delay's power density spectrum ${\it \Phi}_{\rm V}(\Delta \tau)$ by setting the second parameter of ${\it \Phi}_{\rm VZ}(\Delta \tau, \Delta t)$ to $\Delta t = 0$ . The graphic on the right shows an exemplary curve.

The delay's power density spectrum is a central quantity for the description of the mobile communications channel. This has the following characteristics:

- ${\it \Phi}_{\rm V}(\Delta \tau_0)$ is a measure for the "power" of those signal components which are delayed by $\tau_0$ . For this purpose, an implicit averaging over all Doppler frequencies $(f_{\rm D})$ is carried out.

- The delay's power density spectrum ${\it \Phi}_{\rm V}(\Delta \tau)$ has, like ${\it \Phi}_{\rm VZ}(\Delta \tau, \Delta t)$ , the unit $\rm [1/s]$. It characterizes the power distribution over all possible delay times $\tau$.

- In the graphic, the power $ P_0 \approx {\it \Phi}_{\rm V}(\Delta \tau_0)\cdot \Delta \tau$ of those signal components that arrive at the receiver via any path with a delay between $\tau_0 \pm \Delta \tau/2$.

- Normalizing the power density spectrum ${\it \Phi}_{\rm V}(\Delta \tau)$ in such a way that the area is $1$ results in the probability density function $\rm (PDF)$ of the delay time:

- \[{\rm PDF}_{\rm V}(\tau) = \frac{{\it \Phi}_{\rm V}(\tau)}{\int_{0 }^{\infty}{\it \Phi}_{\rm V}(\tau)\hspace{0.15cm}{\rm d}\tau} \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

Note on nomenclature:

- In the book "Stochastic Signal Theory" we would have denoted this probability density Function with $f_\tau(\tau)$.

- To make the connection between ${\it \Phi}_{\rm V}(\Delta \tau)$ and the PDF clear and to avoid confusion with the frequency $f$ we use the nomenclature given here.

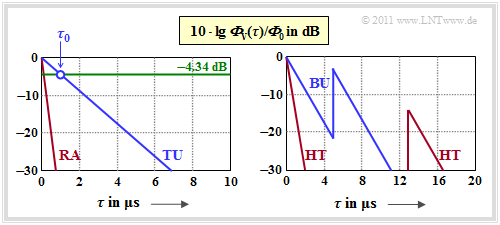

$\text{Example 1: Delay models according to COST 207}$

In the 1990s, the European Union founded the working group COST 207 with the aim to provide standardized channel models for cellular mobile communications. where "COST" stands for "European Cooperation in Science and Technology".

In this international committee profiles for the delay time $\tau$ have been developed, based on measurements and valid for different application scenarios. In the following, four different delay's power density spectra are given, where the normalization factor ${\it \Phi}_0 = {\it \Phi}_{\rm V}(\tau = 0)$ is always used. The graph shows the PDSs of these profiles in logarithmic representation:

(1) profile $\rm RA$ (Rural Area):

- \[{\it \Phi}_{\rm V}(\tau)/{\it \Phi}_{\rm 0} = {\rm e}^{ -\tau / \tau_0} \hspace{0.3cm}\text{for}\hspace{0.2cm} 0 < \tau < 0.7\,{\rm µ s}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.15cm}\tau_0 = 0.109\,{\rm µ s}\hspace{0.05cm}.\]

(2) profile $\rm TU$ (Typical Urban) ⇒ cities and suburbs:

- \[{\it \Phi}_{\rm V}(\tau)/{\it \Phi}_{\rm 0} = {\rm e}^{ -\tau / \tau_0} \hspace{0.3cm}\text{for}\hspace{0.2cm} 0 < \tau < 7\,{\rm µ s}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.15cm}\tau_0 = 1\,{\rm µ s}\hspace{0.05cm}.\]

(3) profile $\rm BU$ (Bad Urban) ⇒ unfavourable conditions in cities:

- \[{\it \Phi}_{\rm V}(\tau)/{\it \Phi}_{\rm 0} = \left\{ \begin{array}{c} {\rm e}^{ -\tau / \tau_0}\\ 0.5 \cdot {\rm e}^{ (5\,{\rm µ s}-\tau) / \tau_0} \end{array} \right.\quad \begin{array}{*{1}l} \hspace{0.1cm} {\rm for}\hspace{0.3cm} 0 < \tau < 5\,{\rm µ s}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.15cm}\tau_0 = 1\,{\rm µ s}\hspace{0.05cm}, \\ \hspace{0.1cm} {\rm for}\hspace{0.3cm} 5\,{\rm µ s} < \tau < 10\,{\rm µ s}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.15cm}\tau_0 = 1\,{\rm µ s} \hspace{0.05cm}. \\ \end{array}\]

(4) profile $\rm HT$ (Hilly Terrain) ⇒ hilly and mountainous regions:

- \[{\it \Phi}_{\rm V}(\tau)/{\it \Phi}_{\rm 0} = \left\{ \begin{array}{c} {\rm e}^{ -\tau / \tau_0}\\ 0.04 \cdot {\rm e}^{ (15\,{\rm µ s}-\tau) / \tau_0} \end{array} \right.\quad \begin{array}{*{1}l} \hspace{-0.25cm} {\rm for}\hspace{0.3cm} 0 < \tau < 2\,{\rm µ s}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.15cm}\tau_0 = 0.286\,{\rm µ s}\hspace{0.05cm}, \\ \hspace{-0.25cm} {\rm for}\hspace{0.3cm} 15\,{\rm µ s} < \tau < 20\,{\rm µ s}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.15cm}\tau_0 = 1\,{\rm µ s} \hspace{0.05cm}. \\ \end{array}\]

One can see from the graphics:

- The exponential functions in linear representation now become straight lines.

- For logarithmic display, you can read the PDS parameter $\tau_0$ for $\rm 10 \cdot lg \ (1/e) = -4.34 \ dB$ as shown in the graph for the $\rm TU$ profile.

- These four COST profiles are described in the Exercise 2.8 in more detail.

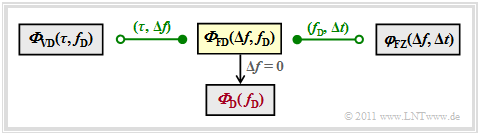

ACF and PDS of the frequency-variant transfer function

The system function $\eta_{\rm FD}(f, f_{\rm D})$ described in the nbsp; overview on the first page of this chapter is also known as the frequency-variant transfer function where the adjective "frequency-variant" refers to the Doppler frequency

The associated ACF is defined as follows:

- \[\varphi_{\rm FD}(f_1, f_{\rm D_1}, f_2, f_{\rm D_2}) = {\rm E} \left [ \eta_{\rm FD}(f_1, f_{\rm D_1}) \cdot \eta_{\rm FZ}^{\star}(f_2, f_{\rm D_2}) \right ]\hspace{0.05cm}. \]

By similar considerations as on the previous page this autocorrelation function can be represented under GWSSUS–conditions as follows

- \[\varphi_{\rm FD}(\Delta f, \Delta f_{\rm D}) = \delta(\Delta f_{\rm D}) \cdot {\it \Phi}_{\rm FD}(\Delta f, f_{\rm D}) \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

The following applies:

- ${\it \Phi}_{\rm FD}(\Delta f, f_{\rm D})$ is the so-called frequency–Doppler's cross power density spectrum, which is highlighted in the graphic at the end of the page by a yellow background.

- The first argument $\Delta f = f_2 - f_1$ takes into account that ACF and PDS depend only on the frequency difference due to the stationarity .

- The factor $\delta (\Delta f_{\rm D})$ with $\Delta f_{\rm D} = f_{\rm D_2} - f_{\rm D_1}$ expresses the uncorrelation of the PDS with respect to the Doppler shift.

- You get from ${\it \Phi}_{\rm FD}(\Delta f, f_{\rm D})$ to Doppler's Power Spectral Density ${\it \Phi}_{\rm D}(f_{\rm D})$ if you set $\Delta f= 0$

- The Doppler's power density spectrum ${\it \Phi}_{\rm D}(f_{\rm D})$ indicates the power with which individual Doppler frequencies occur.

- The probability density of the Doppler frequency is obtained from ${\it \Phi}_{\rm D}(f_{\rm D})$ by suitable surface normalization. The PDF has like ${\it \Phi}_{\rm D}(f_{\rm D})$ the unit $\rm [1/Hz]$

- \[{\rm PDF}_{\rm D}(f_{\rm D}) = \frac{{\it \Phi}_{\rm D}(f_{\rm D})}{\int_{-\infty }^{+\infty}{\it \Phi}_{\rm D}(f_{\rm D})\hspace{0.15cm}{\rm d}f_{\rm D}} \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

- Often, for example for a vertical monopulse antenna in an isotropically scattered field, the ${\it \Phi}_{\rm D}(f_{\rm D})$ given through the Jakes–spectrum .

The frequency–Doppler's cross power density spectrum ${\it \Phi}_{\rm FD}(\Delta f, f_{\rm D})$ is highlighted in yellow.

- The Fourier connections to the neighboring GWSSUS–system description functions are also marked.

- We refer here to the interactive applet The Doppler Effect.

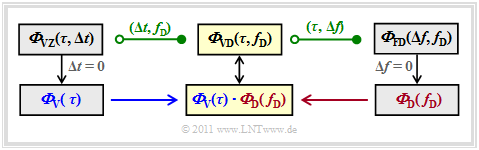

ACF and PDS of the delay Doppler function

The system function shown in the Overview on the first page of this chapter on the left hand side was named $\eta_{\rm VD}(\tau, f_{\rm D})$ . The ACF of this delay–Doppler–function can be written with $\Delta \tau = \tau_2 - \tau_1$ and $\Delta f_{\rm D} = f_{\rm D2} - f_{\rm D1}$ taking into account the GWSSUS properties with $\Delta \tau = \tau_2 - \tau_1$ and $\Delta f_{\rm D}{\rm D2} = f_{\rm D2} - f_{\rm D1}$ as follows

- \[\varphi_{\rm VD}(\tau_1, f_{\rm D_1}, \tau_2, f_{\rm D_2}) = \varphi_{\rm VD}(\Delta \tau, \Delta f_{\rm D}) = \delta(\Delta \tau) \cdot {\rm \delta}(\Delta f_{\rm D}) \cdot {\it \Phi}_{\rm VD}(\tau, f_{\rm D}) \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

It should be noted about this equation:

- The first Dirac function $\delta (\delta \tau)$ takes into account that the delays are uncorrelated ("Uncorrelated Scattering").

- The second Dirac function $\delta (\Delta f_{\rm D})$ follows from the stationarity ("Wide Sense Stationary").

- The delay–Doppler's PDS ${\it \Phi}_{\rm VD}(\tau, f_{\rm D})$ , also called Scatter–PDS , can be derived from ${\it \Phi}_{\rm VZ}(\tau, \Delta t)$ or ${\it \Phi}_{\rm FD}(\Delta f, f_{\rm D})$ :

- \[{\it \Phi}_{\rm VD}(\tau, f_{\rm D}) ={\rm F}_{\Delta t} \big [ {\it \Phi}_{\rm VZ}(\tau, \Delta t) \big ] = \int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} {\it \Phi}_{\rm VZ}(\tau, \Delta t) \cdot {\rm e}^{- {\rm j}\hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm}2 \pi \hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm}f_{\rm D} \hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm}\Delta t}\hspace{0.15cm}{\rm d}\Delta t \hspace{0.05cm},\]

- \[{\it \Phi}_{\rm VD}(\tau, f_{\rm D}) = {\rm F}_{f_{\rm D}}^{-1} \big [ {\it \Phi}_{\rm FD}(\Delta f, f_{\rm D}) \big ] = \int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} {\it \Phi}_{\rm FD}(\Delta f, f_{\rm D}) \cdot {\rm e}^{+{\rm j}\hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm} 2 \pi \hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm} \tau \hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm} \Delta f}\hspace{0.15cm}{\rm d}\Delta f \hspace{0.05cm}. \]

- Both the system function $\eta_{\rm VD}(\tau, f_{\rm D})$ and the derived functions $\varphi _{\rm VD}(\delta \tau, \delta f_{\rm D})$ and ${\it \Phi}_{\rm VD}(\tau, f_{\rm D})$ are dimensionless. For more information on this, see the specification for Exercise 2.6.

- Furthermore, if the GWSSUS requirements are met, the scatter function is equal to the product of the delay's and Doppler's PDSs:

- \[{\it \Phi}_{\rm VD}(\tau, f_{\rm D}) = {\it \Phi}_{\rm V}(\tau) \cdot {\it \Phi}_{\rm D}(f_{\rm D})\hspace{0.05cm}.\]

$\text{Conclusion:}$ The figure summarizes the results of this chapter so far.

It should be noted that

(1) The influence of the delay time $\tau$ and the Doppler frequency $f_{\rm D}$ can be separated into

- the blue power density spectrum ${\it \Phi}_{\rm V}(\tau)$, and

- the red power density spectrum ${\it \Phi}_{\rm D}(f_{\rm D})$.

(2) The 2D–Delay–Doppler's PDS ${\it \Phi}_{\rm VD}(\tau, f_{\rm D})$ is equal to the product of these two fractions.

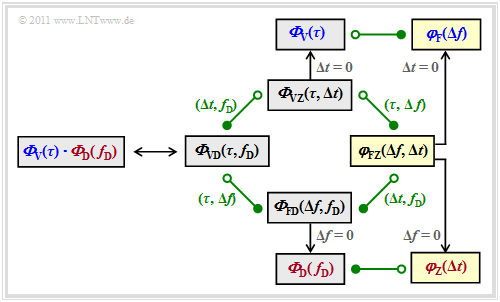

ACF and PDS of the time variant transfer function

The following diagram shows all the relationships between the individual power spectral densities once again in compact form.

This has already been discussed on the last pages:

$${\it \Phi}_{\rm VZ}(\tau, \delta t)\hspace{0.55cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}\text{with} \hspace{0.2cm}\delta t = 0\text{:} \hspace{0.2cm} {\it \Phi}_{\rm V}(\tau),$$

- $${\it \Phi}_{\rm FD}(\Delta f, f_{\rm D})\hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}\text{with} \hspace{0.2cm}\Delta f = 0\text{:} \hspace{0.2cm} {\it \Phi}_{\rm D}( f_{\rm D}),$$

- $${\it \Phi}_{\rm VD}(\tau, f_{\rm D})= {\it \Phi}_{\rm V}(\tau) \cdot {\it \Phi}_{\rm D}(f_{\rm D})\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

The frequency–time's Correlation function

(marked yellow in the adjacent graph) has not yet been considered:

- \[\varphi_{\rm FZ}(f_1, t_1, f_2, t_2) = {\rm E} \left [ \eta_{\rm FZ}(f_1, t_1) \cdot \eta_{\rm FZ}^{\star}(f_2, t_2) \right ]\hspace{0.05cm}.\]

Considering again the GWSSUS simplifications and the identity $\eta_{\rm FZ}(f, \hspace{0.05cm}t) = H(f, \hspace{0.05cm}t)$, the ACF can be also written with $\Delta f = f_2 - f_1$ and $\Delta t = t_2 - t_1$ as follows:

- \[\varphi_{\rm FZ}(f_1, t_1, f_2, t_2) \hspace{0.3cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}\varphi_{\rm FZ}(\Delta f, \Delta t) = {\rm E} \big [ H(f, t) \cdot H^{\star}(f + \Delta f, t + \Delta t) \big ]\hspace{0.05cm}.\]

It should be noted in this respect:

- You can see from the name that $\varphi_{\rm FZ}(\Delta f, \Delta t)$ is a correlation function and not a power density spectrum like the functions $\varphi_{\rm FZ}(\Delta f, \Delta t)$ ${\it \Phi}_{\rm VZ}(\tau, \Delta t)$, ${\it \Phi}_{\rm FD}(\Delta f, f_{\rm D})$ and ${\it \Phi}_{\rm VD}(\tau, f_{\rm D})$.

- The Fourier connections with the neighboring functions are:

- \[{\it \Phi}_{\rm VZ}(\tau, \Delta t) \hspace{0.2cm} \stackrel{\tau, \hspace{0.05cm}\Delta f}{\circ\!\!-\!\!\!-\!\!\!-\!\!\bullet} \hspace{0.2cm} \varphi_{\rm FZ}(\Delta f, \hspace{0.05cm}\Delta t) \hspace{0.2cm} \stackrel{\Delta t,\hspace{0.05cm} f_{\rm D}}{\circ\!\!-\!\!\!-\!\!\!-\!\!\bullet} \hspace{0.2cm} {\it \Phi}_{\rm FD}(\Delta f,\hspace{0.05cm} f_{\rm D}) \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

- If you set the parameters $\Delta t = 0$ or $\Delta f = 0$ in this 2D– function, the separate correlation functions for the frequency domain or the time domain result:

- \[\varphi_{\rm F}(\Delta f) = \varphi_{\rm FZ}(\Delta f, \Delta t = 0) \hspace{0.05cm},\]

- \[\varphi_{\rm Z}(\Delta t) = \varphi_{\rm FZ}(\Delta f = 0, \Delta t ) \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

- From the above graph it is also clear that these correlation functions correspond to the derived power spectral densities via Fourier transformation:

- \[\varphi_{\rm F}(\Delta f) \hspace{0.2cm} {\bullet\!\!-\!\!\!-\!\!\!-\!\!\circ} \hspace{0.2cm} {\it \Phi}_{\rm V}(\tau)\hspace{0.05cm},

\hspace{0.4cm}\varphi_{\rm Z}(\Delta t) \hspace{0.2cm} {\circ\!\!-\!\!\!-\!\!\!-\!\!\bullet} \hspace{0.2cm} {\it \Phi}_{\rm D}(f_{\rm D})\hspace{0.05cm}.\]

Parameters of the GWSSUS model

According to the results on the last page, the mobile channel is replaced by

- the delay–power density spectrum ${\it \Phi}_{\rm V}(\tau)$ and

- the Doppler–power density spectrum ${\it \Phi}_{\rm D}(f_{\rm D})$

By suitable normalization to the respective area $1$ the density functions result with respect to the delay time $\tau$ or the Doppler frequency $f_{\rm D}$.

Characteristic values can be derived from the power spectral densities or the corresponding correlation functions. The most important ones are listed here:

$\text{Definition:}$ The Multipath Spread or Time Delay Spread $T_{\rm V}$ specifies the spread that a Dirac impulse experiences through the channel on statistical average. $T_{\rm V}$ is defined as the standard deviation $(\sigma_{\rm V})$ the random variable $\tau$:

- \[T_{\rm V} = \sigma_{\rm V} = \sqrt{ {\rm E} \big [ \tau^2 \big ] - m_{\rm V}^2} \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

- The mean value $m_{\rm V} = {\rm E}\big[\tau \big]$ is a "Average Excess Delay" for all signal components.

- ${\rm E} \big [ \tau^2 \big ] $ is to be calculated as the root mean square value.

$\text{Definition:}$ The Coherence Bandwidth $B_{\rm K}$ is the $\Delta f$–value at which the frequency's correlation function has dropped to half of its value for the first time.

- \[\vert \varphi_{\rm F}(\Delta f = B_{\rm K})\vert \stackrel {!}{=} {1}/{2} \cdot \vert \varphi_{\rm F}(\Delta f = 0)\vert \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

- $B_{\rm K}$ is a measure of the minimum frequency difference by which two harmonic oscillations must differ in order to have completely different channel transmission characteristics.

- If the signal bandwidth is $B_{\rm S} <B_{\rm K}$, then all spectral components are changed in approximately the same way by the channel.

This means: Precisely then there is a non-frequency selective fading.

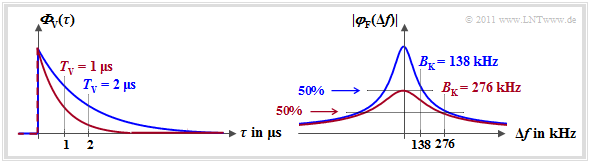

$\text{Example 2:}$ The graphic on the left side shows the delay's power density ${\it \Phi}_{\rm V}(\tau)$

- with $T_{\rm V} = 1 \ \rm µs$ (red curve),

- with $T_{\rm V} = 2 \ \rm µs$ (blue curve).

In the right-hand $\varphi_{\rm F}(\delta f)$–representation, the coherence bandwidths are drawn in:

- $B_{\rm K} = 276 \ \rm kHz$ (red curve),

- $B_{\rm K} = 138 \ \rm kHz$ (blue curve).

You can see from these numerical values

- The multipath spread $T_{\rm V}$ ,obtainable from ${\it \Phi}_{\rm V}(\tau)$ , and the coherence bandwidth $B_{\rm K}$ ,determined by $\varphi_{\rm F}(\delta f)$ , stand in a fixed relation to each other: $B_{\rm K} \approx 0.276/T_{\rm V}$.

- The often used approximation $B_{\rm K}\hspace{0.02cm}' \approx 1/T_{\rm V}$ is, however, very inaccurate at exponential ${\it \Phi}_{\rm V}(\tau)$ .

Let us now consider the time variance characteristics derived from the time correlation function $\varphi_{\rm Z}(\delta t)$ or from the Doppler's PDS ${\it \Phi}_{\rm D}(f_{\rm D})$ :

$\text{Definition:}$ The Correlation Time $T_{\rm D}$ specifies the average time that must elapse until the channel has completely changed its transmission properties due to the time variance. Its definition is similar to the definition of the coherence bandwidth:

- \[\vert \varphi_{\rm Z}(\Delta t = T_{\rm D})\vert \stackrel {!}{=} {1}/{2} \cdot \vert \varphi_{\rm Z}(\Delta t = 0)\vert \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

$\text{Definition:}$ The Doppler Spread $B_{\rm D}$ is the average frequency broadening that the individual spectral signal components experience. The calculation is similar to multipath broadening in that the Doppler spread $B_{\rm D}$ is calculated as the standard deviation of the random quantity $f_{\rm D}$ :

- \[B_{\rm D} = \sigma_{\rm D} = \sqrt{ {\rm E} \left [ f_{\rm D}^2 \right ] - m_{\rm D}^2} \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

- First of all, the Doppler–PDF is to be determined from ${\it \Phi}_{\rm D}(f_{\rm D})$ through area normalization to $1$

- This results in the mean Doppler shift $m_{\rm D} = {\rm E}[f_{\rm D}]$ and the standard deviation $\sigma_{\rm D}$.

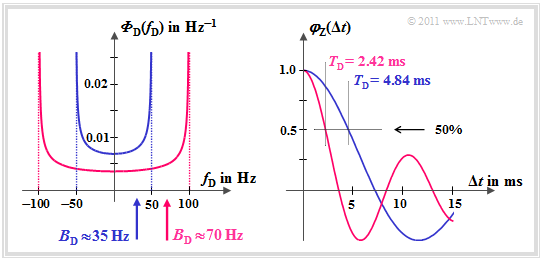

$\text{Example 3:}$ The diagram is valid for a time variant channel without direct component. Shown on the left is the Jakes–Spectrum ${\it \Phi}_{\rm D}(f_{\rm D})$.

The Doppler spread $B_{\rm D}$ can be determined from this:

- \[f_{\rm D,\hspace{0.05cm}max} = 50\,{\rm Hz}\hspace{-0.1cm}: \hspace{-0.1cm}\hspace{0.45cm} B_{\rm D} \approx 35\,{\rm Hz} \hspace{0.05cm},\]

- \[f_{\rm D,\hspace{0.05cm}max} = 100\,{\rm Hz}\hspace{-0.1cm}: \hspace{-0.1cm}\hspace{0.2cm} B_{\rm D} \approx 70\,{\rm Hz} \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

The time correlation function $\varphi_{\rm Z}(\Delta t)$ is sketched on the right, as the Fourier transform of ${\it \Phi}_{\rm D}(f_{\rm D})$ .

This can be expressed given boundary conditions and with the Bessel function as:

- \[\varphi_{\rm Z}(\Delta t \hspace{-0.05cm} = \hspace{-0.05cm}T_{\rm D}) \hspace{-0.05cm}= \hspace{-0.05cm} {\rm J}_0(2 \pi \hspace{-0.05cm} \cdot \hspace{-0.05cm} f_{\rm D,\hspace{0.05cm}max} \hspace{-0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{-0.05cm}\Delta t ).\]

- The correlation duration of the blue curve is $T_{\rm D} = 4.84 \ \rm ms$.

- For $f_{\rm D,\hspace{0.05cm}max} = 100\,{\rm Hz}$ the correlation duration is only half.

- In this case, it geneally applies: $B_{\rm D} \cdot T_{\rm D}\approx 0.17$.

Simulation according to the GWSSUS model

The Monte–Carlo–method, shortly described for the simulation of a GWSSUS mobile communication channel is based on work by Rice [Ric44][1] and Höher [Höh90][2].

- The 2D–impulse response is represented by a sum of $M$ complex exponential functions. $M$ can be interpreted as the number of different paths:

- \[h(\tau,\ t)= \frac{1}{\sqrt {M}} \cdot \sum_{m=1}^{M} \alpha_m \cdot \delta (t - \tau_m) \cdot {\rm e}^{{\rm j} \hspace{0.05cm} \phi_{m} }\cdot {\rm e}^{ {\rm j} \hspace{0.05cm}2 \pi f_{{\rm D},\hspace{0.05cm} m} t} \hspace{0.05cm}. \]

- First, the delays $\tau_m$, the attenuation factors $\alpha_m$, the equally distributed phases $\phi_m$ and the Doppler frequencies $f_{{\rm D},\hspace{0.05cm} m}$ will be randomly generated according to the GWSSUS specifications. The base for the random generation of the Doppler frequencies $f_{{\rm D},\hspace{0.05cm} m}$ is the Jakes–Spectrum ${\it \Phi}_{\rm D}(f_{\rm D})$, which, appropiately normalized, simultaneously indicates the PDF of the Doppler frequencies.

- Because of ${\it \Phi}_{\rm VD}(\tau, f_{\rm D}) = {\it \Phi}_{\rm V}(\tau) \cdot {\it \Phi}_{\rm D}(f_{\rm D})$  the delay time $\tau_m$ is independent of the Doppler frequency $f_{{\rm D},\hspace{0.05cm} m}$ for all $m$ . This is valid with good approximation, for terrestrial land mobile communication. For the random generation of the parameters $\alpha_m$ and $\tau_m$, which determine the delay–power density spectrum $ {\it \Phi}_{\rm V}(\tau)$ the following COST profiles are available: $\rm RA$ (Rural Area), $\rm TU$ (Typical Urban), $\rm BU$ (Bad Urban) and $\rm HT$ (Hilly Terrain).

- The greater the number of different paths $M$ is chosen for the simulation, the better a real impulse response is approximated by the above equation. However, the higher accuracy of the siulation is at the expense of its duration. In the literature, favorable values are given for $M$ between $100$ and $600$ .

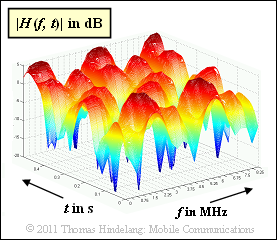

$\text{Example 4:}$ The graphic from [Hin08][3] shows a simulation result: $20 \cdot \lg \vert H(f, \hspace{0.1cm}t)}t)\vert$ is shown as a 2D–plot, where the time-variant transfer function $H(f, \hspace{0.1cm}t)$ is also referred to as $\eta_{\rm FZ}(f, \hspace{0.1cm}t)$ in this tutorial .

The simulation is based on the following parameters:

- The time variance results from a movement with $v = 3 \ \rm km/h$.

- The carrier frequency is $f_{\rm T} = 2 \ \rm GHz$.

- The maximum delay time is $\tau_{\rm max} \approx 0.4 \ \rm µ s$.

- According to the approximation we obtain the coherence bandwidth $B_{\rm K}\hspace{0.02cm}' \approx 2.5 \ \rm MHz$.

- The maximum Doppler frequency is $f_\text{D, max} \approx 5.5 \ \rm Hz$.

- The Doppler spread results in $B_{\rm D} \approx 4 \ \rm Hz$.

Exercises to the chapter

Exercise 2.5: Scatter Function

Exercise 2.5Z: Multi-Path Scenario

Exercise 2.6: Dimensions in GWSSUS

Exercise 2.7: Coherence Bandwidth

Exercise 2.7Z: Coherence Bandwidth of the LTI Two-Path Channel

Exercise 2.8: COST Delay Models

List of sources

- ↑ Rice, S.O.: Mathematical Analysis of Random Noise. BSTJ–23, pp. 282–232 und BSTJ–24, pp. 45–156, 1945.

- ↑ Höher, P.: Empfang trelliscodierter PSK–Signale auf frequenzselektiven Mobilfunkkanälen – Entzerrung, Decodierung und Kanalschätzung. Düsseldorf: VDI–Verlag, Fortschrittsberichte, Reihe 10, Nr. 147, 1990.

- ↑ Hindelang, T.: Mobile Communications. Vorlesungsmanuskript. Lehrstuhl für Nachrichtentechnik, TU München, 2008.