Difference between revisions of "Digital Signal Transmission/Linear Digital Modulation - Coherent Demodulation"

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

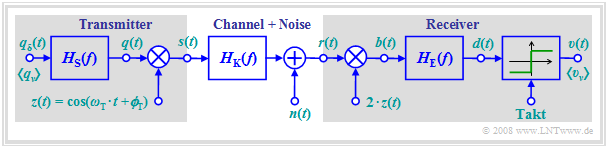

== Common block diagram for ASK and BPSK == | == Common block diagram for ASK and BPSK == | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | [[File: | + | [[File:EN_Dig_T_4_1_S1.png|right|frame|Block diagram, valid for both an ASK and BPSK transmission system equally|class=fit]] |

In the chapter [[Modulation_Methods/Linear_Digital_Modulation|Linear Digital Modulation]] of the book "Modulation Methods" the digital carrier frequency systems | In the chapter [[Modulation_Methods/Linear_Digital_Modulation|Linear Digital Modulation]] of the book "Modulation Methods" the digital carrier frequency systems | ||

* [[Modulation_Methods/Linear_Digital_Modulation#ASK_.E2.80.93_Amplitude_Shift_Keying|ASK]] (<i>Amplitude Shift Keying</i>) and | * [[Modulation_Methods/Linear_Digital_Modulation#ASK_.E2.80.93_Amplitude_Shift_Keying|ASK]] (<i>Amplitude Shift Keying</i>) and | ||

| Line 52: | Line 52: | ||

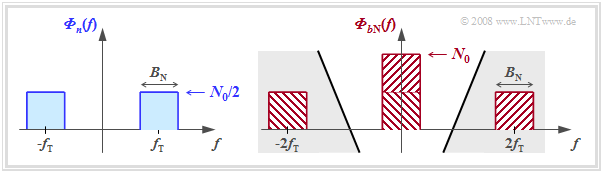

The observations just made show that to calculate the error probability of the BPSK system, one can dispense with the two multiplications by $z(t)$ and $z_{\rm E}(t) = 2 \cdot z(t)$ if one doubles the noise power. | The observations just made show that to calculate the error probability of the BPSK system, one can dispense with the two multiplications by $z(t)$ and $z_{\rm E}(t) = 2 \cdot z(t)$ if one doubles the noise power. | ||

| − | [[File: | + | [[File:EN_Dig_T_4_1_S2b.png|center|frame|Equivalent circuit diagram of the BPSK|class=fit]] |

This results in AWGN noise for the noise power before the decision: | This results in AWGN noise for the noise power before the decision: | ||

| Line 104: | Line 104: | ||

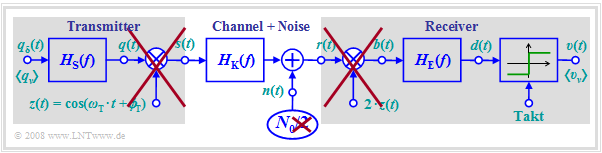

The diagram shows the bit error probabilities of ASK and BPSK depending on the quotient $E_{\rm B}/N_0$. This plot is suitable for comparison between these binary modulation schemes under the constraint of power limitation: | The diagram shows the bit error probabilities of ASK and BPSK depending on the quotient $E_{\rm B}/N_0$. This plot is suitable for comparison between these binary modulation schemes under the constraint of power limitation: | ||

| − | [[File: | + | [[File:EN_Dig_T_4_1_S3.png|right|frame|Bit error probabilities of ASK and BPSK|class=fit]] |

One can see from this double logarithmic plot: | One can see from this double logarithmic plot: | ||

| Line 133: | Line 133: | ||

| − | [[File: | + | [[File:EN_Dig_T_4_1_S4.png|right|frame|Phase diagrams for BPSK with cosine carrier (left) and minus sinusoidal carrier (right)|class=fit]] |

{{GraueBox|TEXT= | {{GraueBox|TEXT= | ||

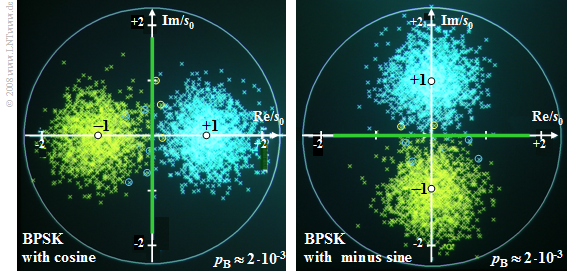

$\text{Example 1:}$ The diagram shows two different phase diagrams of ''Binary Phase Shift Keying'' (BPSK): | $\text{Example 1:}$ The diagram shows two different phase diagrams of ''Binary Phase Shift Keying'' (BPSK): | ||

| Line 168: | Line 168: | ||

Prerequisite for the validity of the previous equations is a strict synchronicity between the carrier signals added at the transmitter and receiver. Now, a phase offset $\Delta \phi_{\rm T}$ between the two carrier signals $z(t)$ and $z_{\rm E} (t)$ is assumed, while frequency synchronicity is still assumed. | Prerequisite for the validity of the previous equations is a strict synchronicity between the carrier signals added at the transmitter and receiver. Now, a phase offset $\Delta \phi_{\rm T}$ between the two carrier signals $z(t)$ and $z_{\rm E} (t)$ is assumed, while frequency synchronicity is still assumed. | ||

| − | [[File: | + | [[File:EN_Dig_T_4_1_S5.png|right|frame|Phase diagrams for BPSK and 4-QAM with $\Delta \phi_{\rm T} = 30 ^\circ$.|class=fit]] |

The diagram shows the phase diagrams for $\Delta \phi_{\rm T} = 30^\circ$. It can be seen: | The diagram shows the phase diagrams for $\Delta \phi_{\rm T} = 30^\circ$. It can be seen: | ||

| Line 201: | Line 201: | ||

| − | [[File: | + | [[File:EN_Dig_T_4_1_S6.png|center|frame|Block diagram and equivalent baseband model for coherent ASK and BPSK|class=fit]] |

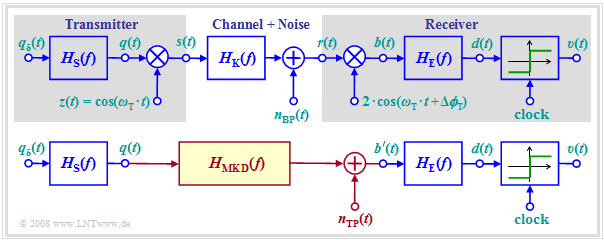

If one assumes the '''equivalent baseband model''' according to the diagram below, the calculation of the signals after the demodulator can be simplified: | If one assumes the '''equivalent baseband model''' according to the diagram below, the calculation of the signals after the demodulator can be simplified: | ||

Revision as of 16:45, 28 April 2022

Contents

- 1 Common block diagram for ASK and BPSK

- 2 Noise consideration for the BPSK system

- 3 Error probability of the optimal BPSK system

- 4 Error probability of the optimal ASK system

- 5 Error probabilities for 4–QAM and 4–PSK

- 6 Phase offset between transmitter and receiver

- 7 Baseband model for ASK and BPSK

- 8 Exercises for the chapter

Common block diagram for ASK and BPSK

In the chapter Linear Digital Modulation of the book "Modulation Methods" the digital carrier frequency systems

have already been described in detail. In this chapter, the bit error probability of these systems is now calculated, assuming the outlined common block diagram.

In the following, the following assumptions apply again:

- Demodulation always occurs coherently. That means: A carrier signal $z_{\rm E}(t)$ with the same frequency as at the transmitter but with double amplitude is added at the receiver. Let the phase offset between the transmitter carrier signal $z(t)$ and the receiver carrier signal $z_{\rm E}(t)$ initially be $\Delta \phi_{\rm T} = 0$.

- For BPSK, the bipolar amplitude coefficients $a_\nu \in \{-1, +1\}$ are assumed and the decision threshold is $E = 0$. In contrast, for ASK, $a_\nu \in \{0, 1\}$ is valid. The decision threshold $E$ is to be chosen as best as possible for this unipolar case.

- We always consider the AWGN channel, that is, for the channel frequency response $H_{\rm K}(f) = 1$ and $n(t)$ represents white Gaussian noise with (one-sided) noise power density $N_0$.

- The equalization of linear channel distortions – i.e., the case $H_{\rm K}(f) \ne \rm const.$ – is possible in the same way as for baseband transmission. For this, please refer to the chapter Consideration of Channel Distortion and Equalization.

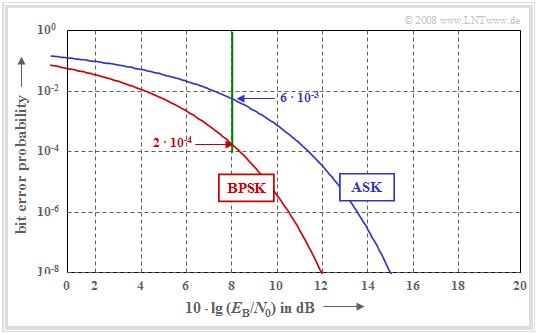

Noise consideration for the BPSK system

We first assume a bipolar rectangular source signal $q(t)$ with the values $\pm s_0$. Its normalized spectrum is: $H_{\rm S}(f) = {\rm si}(\pi f T)$.

Just as in baseband transmission, the smallest possible bit error probability for the receiver filter is $H_{\rm E}(f) = {H_{\rm S} }^\star(f) = {\rm si}(\pi f T)$. The signal waveforms of this matched filter receiver BPSK system show:

- The signal component of the detection signal $d_{\rm S}(t)$ – i.e., without noise component – is always $\pm s_0$ at all detection times $\nu \cdot T$, with the signs determined by the amplitude coefficients $a_\nu \in \{-1, +1\}$.

- As for the comparable baseband system, the error probability is $p_{\rm B} = {\rm Q}(s_0/\sigma_d)$, with the complementary Gaussian error interval ${\rm Q}(x)$.

Different from the baseband system, however, is the noise power. The noise component $b_{\rm N}(t)$ is obtained by multiplying the bandpass noise $n(t)$ by the receiver-side carrier $z_{\rm E}(t) =2 \cdot \cos(2\pi f t)$ and has the noise power density

- $${\it \Phi}_{b{\rm N}}(f)={\it \Phi}_{n}(f) \star \big[ 1^2 \cdot \delta ( f - f_{\rm T})+ 1^2 \cdot \delta ( f + f_{\rm T})\big].$$

The diagram illustrates this equation using bandlimited white noise with bandwidth $B_n$ as an example:

- While ${\it \Phi}_{n}(f = f_{\rm T}) = N_0/2$ holds, ${\it \Phi}_{b{\rm N}}(f=0) = N_0$.

- The components around $\pm 2f_{\rm T}$ are eliminated by the subsequent receiver filter $H_{\rm E}(f)$ and do not matter for further considerations.

- For true white noise, with the $B_n \to \infty$ boundary transition, for all frequencies:

- $${{\it \Phi}_{n}(f)}={N_0}/{2}, \hspace{0.3cm}{{\it \Phi}_{b{\rm N}}(f)}={N_0}.$$

Error probability of the optimal BPSK system

The observations just made show that to calculate the error probability of the BPSK system, one can dispense with the two multiplications by $z(t)$ and $z_{\rm E}(t) = 2 \cdot z(t)$ if one doubles the noise power.

This results in AWGN noise for the noise power before the decision:

- $$\sigma_d^2 = N_0 \cdot \int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} {\rm si}^2(\pi \hspace{0.01cm} f \hspace{0.05cm} T_{\rm B}) \,{\rm d} f = {N_0}/{T_{\rm B}},$$

i.e., twice the value as for baseband transmission. Note: To allow later comparison with quadrature amplitude modulation (QAM), the symbol duration $T$ has been replaced here by the bit duration $T_{\rm B}$. However, $T_{\rm B}=T$ is valid for BPSK (and also for ASK).

$\text{Conclusion:}$ Thus, the BPSK error probability with the two usual Gaussian error functions is:

- $$p_{\rm B} = {\rm Q}\left ( \sqrt{\frac{s_0^2 \cdot T_{\rm B} }{N_0 } }\hspace{0.1cm} \right ) = {1}/{2}\cdot {\rm erfc}\left ( \sqrt{\frac{s_0^2 \cdot T_{\rm B} }{2 \cdot N_0 } }\hspace{0.1cm} \right ).$$

If one further considers that the energy expended per bit with BPSK is

- $$E_{\rm B} = {1}/{2}\cdot s_0^2 \cdot T_{\rm B}$$

this equation can be transformed as follows:

- $$p_{\rm B} = {\rm Q}\left ( \sqrt{ {2 \cdot E_{\rm B} }/{N_0 } } \hspace{0.1cm}\right ) ={1}/{2}\cdot {\rm erfc}\left ( \sqrt{ {E_{\rm B} }/{N_0 } } \hspace{0.1cm}\right ).$$

This results in exactly the same formula as for baseband transmission, but where $E_{\rm B} = s_0^2 \cdot T_{\rm B}$ had to be used for the "energy per bit" and not $E_{\rm B} = {1}/{2}\cdot s_0^2 \cdot T_{\rm B}$.

Note: This last equation holds not only for rectangular source signal

⇒ $H_{\rm S}(f) = {\rm si}(\pi f T)$, but for any $H_{\rm S}(f)$, as long as

- the receiver filter $H_{\rm E}(f) = {H_{\rm S} }^\star(f)$ is exactly matched to the transmitter, and

- the product $H_{\rm S}(f) \cdot H_{\rm E}(f)$ satisfies the first Nyquist criterion.

Error probability of the optimal ASK system

We now consider an ASK system under the same conditions as the BPSK system. Here

- all signal component values of the detection signal $d_{\rm S}(\nu \cdot T)$ are either $0$ or $s_0$,

- accordingly their distance from the threshold $E = s_0/2$ is in each case $s_0/2$,

- the noise rms value $\sigma_d= \sqrt{N_0}/{T_{\rm B}}$ is exactly the same as for BPSK,

- the energy per bit is only half as large as for BPSK: $E_{\rm B} = {1}/{4}\cdot s_0^2 \cdot T_{\rm B}.$

$\text{Conclusion:}$ Thus the corresponding equations for the ASK error probability as a function of $s_0$ and of $E_{\rm B}$ are:

- $$p_{\rm B} = {\rm Q}\left ( \frac{s_0/2}{\sigma_d } \right )= {\rm Q}\left ( \sqrt{\frac{s_0^2 \cdot T_{\rm B} }{4 \cdot N_0 } } \hspace{0.1cm}\right ),\hspace{1cm}p_{\rm B} = {\rm Q}\left ( \sqrt{\frac{E_{\rm B} }{N_0 } } \hspace{0.1cm}\right ) = {1}/{2}\cdot {\rm erfc}\left ( \sqrt{\frac{E_{\rm B} }{2 \cdot N_0 } } \right ).$$

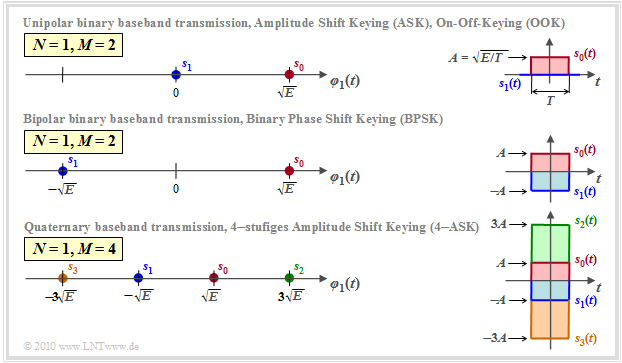

The diagram shows the bit error probabilities of ASK and BPSK depending on the quotient $E_{\rm B}/N_0$. This plot is suitable for comparison between these binary modulation schemes under the constraint of power limitation:

One can see from this double logarithmic plot:

- The ASK curve is $3 \ \rm dB$ to the right of the BPSK curve.

- For the error probability $p_{\rm B} = 10^{-8}$, one needs about $10 \cdot \lg (E_{\rm B}/N_0) = 12 \ \rm dB$ for BPSK, but about $15 \ \rm dB$ for ASK.

- The system comparison at the fixed abscissa value $10 \cdot \lg (E_{\rm B}/N_0) = 8 \ \rm dB$ yields $p_{\rm B} = 2 \cdot 10^{-4}$ for BPSK and $p_{\rm B} = 6 \cdot 10^{-3}$ for ASK.

Error probabilities for 4–QAM and 4–PSK

Quadrature amplitude modulation (QAM) has already been described in detail in the book "Modulation Methods". From the signal space mapping and the signal waveforms it can be seen:

- The 4–QAM can be represented by two mutually orthogonal BPSK systems with cosine and minus–sine carriers, respectively.

- The binary source signal $q(t)$ with bit duration $T_{\rm B}$ ⇒ bit rate $R_{\rm B}$ is split into two sub-signals $q_{\rm I}(t)$ ⇒ in-phase component and $q_{\rm Q}(t)$ ⇒ quadrature component with half rate each (serial–parallel–conversion ). The symbol duration of $q_{\rm I}(t)$ and $q_{\rm Q}(t)$, respectively, is $T = 2\cdot T_{\rm B}$ ; the symbol rate is each $R_{\rm B}/2$.

- The amplitudes of the two mutually orthogonal carrier signals are chosen to be smaller by a factor of $\sqrt{2}$ than in BPSK, so that the envelope of the transmitted signal $s(t)$ is again $s_0$.

The QAM error probability is the same as that of the two orthogonal BPSK systems. Because of the smaller signal amplitude and the lower symbol rate, the following applies:

- $$p_{\rm B} = {\rm Q}\left ( \frac{s_0/\sqrt{2}}{\sigma_d } \right ) \hspace{0.3cm}{\rm with}\hspace{0.3cm}{\sigma_d}^2 = \frac{N_0 }{2 \cdot T_{\rm B}} \hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}p_{\rm B} = {\rm Q}\left ( \sqrt{\frac{s_0^2 }{2} \cdot \frac{2 \cdot T_{\rm B} }{N_0}}\hspace{0.1cm}\right )= {\rm Q}\left ( \sqrt{{2 \cdot E_{\rm B}}/{N_0 }} \hspace{0.1cm}\right ).$$

$\text{Conclusion:}$

- Although 4–QAM can transmit twice the amount of information compared to BPSK, it results in exactly the same bit error probability $E_{\rm B}/{N_0 }$ as a function of $p_{\rm B}$.

- It is taken into account here that also for 4–QAM the following applies for the average energy per bit: $E_{\rm B} = {1}/{2}\cdot s_0^2 \cdot T_{\rm B}.$

- Since quaternary phase modulation (4–PSK) differs from 4–QAM only by a phase shift of $45^\circ$, the same bit error probability also results for 4–PSK when suitable decision regions are considered.

$\text{Example 1:}$ The diagram shows two different phase diagrams of Binary Phase Shift Keying (BPSK):

- The two diagrams differ only in the carrier phase. In both cases, $10 \cdot \lg (E_{\rm B}/N_0) = 6 \ \rm dB$.

- In the left diagram, bit errors (highlighted by circles) are indicated by yellow crosses to the right of the vertical decision threshold and by blue crosses in the left half plane.

- In the right diagram, yellow crosses above the horizontal threshold and blue crosses below indicate bit errors.

- The distance of the useful samples without noise (marked by the white dots) from the respective decision threshold (marked in green) is each $s_0$.

- The variance of the detection samples – recognizable by the radius of the point clouds – is due to $E_{\rm B} = {1}/{2}\cdot s_0^2 \cdot T_{\rm B}$ equal to

- $$\sigma_d^2 = \frac{N_0 }{ T_{\rm B} }= \frac{s_0^2/2 }{ E_{\rm B}/N_0}.$$

- With $10 \cdot \lg (E_{\rm B}/N_0) = 6 \ \rm dB$ ⇒ $E_{\rm B}/N_0 = 10^{0.6} \approx 4$ this gives:

- $$ {\sigma_d^2 }/{ {s_0}^2}= \big [ { 2 \cdot 10^{0.6} }\big ]^{-1} \approx 0.125\hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} { {\sigma_d} }/{ {s_0} }\approx 0.35 \hspace{0.5cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.5cm}p_{\rm B} = {\rm Q}\left ( s_0/{\sigma_d } \right )= {\rm Q}\left ( \sqrt{2 \cdot 10^{0.6} } \hspace{0.08cm}\right ) = {\rm Q}(2.8) \approx 2 \cdot 10^{-3}.$$

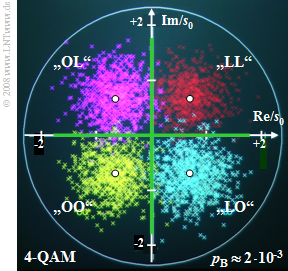

$\text{Example 2:}$ Now we consider a phase diagram of 4–QAM, which can be thought of as two orthogonal BPSK systems with cosine and minus sinusoidal carriers.

- Here, a bit error occurs when the horizontal or the vertical decision threshold is exceeded.

- In the diagram, such a bit error can be recognized when a cross does not match its quadrant in terms of color.

- The distance of the now four useful samples without noise (white dots) from the origin is again $s_0$.

- However, the distance to the decision thresholds is smaller by a factor of $\sqrt{2}$ for 4–QAM than for BPSK.

- The noise rms value $\sigma_d$ is smaller for 4–QAM than for BPSK by the same factor $\sqrt{2}$.

- Thus, the bit error probabilities of 4–QAM and BPSK are the same: $p_{\rm B} \approx 2 \cdot 10^{-3}.$

Phase offset between transmitter and receiver

Prerequisite for the validity of the previous equations is a strict synchronicity between the carrier signals added at the transmitter and receiver. Now, a phase offset $\Delta \phi_{\rm T}$ between the two carrier signals $z(t)$ and $z_{\rm E} (t)$ is assumed, while frequency synchronicity is still assumed.

The diagram shows the phase diagrams for $\Delta \phi_{\rm T} = 30^\circ$. It can be seen:

- For both BPSK (left) and 4–QAM (right), a phase offset by $\Delta \phi_{\rm T}$ causes a corresponding rotation of the phase diagram.

- With BPSK, the phase shift causes a smaller useful signal by $\cos\Delta \phi_{\rm T}$. We have already noticed the same effect with the synchronous demodulator of an analog transmission system.

- Consequently, the distance of the signal component of the detection signal from the decision threshold also becomes smaller by the same factor, which leads to a higher error probability:

- $$p_{\rm B} = {\rm Q}\left ( \sqrt{{2 \cdot E_{\rm B}}/{N_0 }} \hspace{0.1cm}\cdot \cos({\rm \Delta} \phi_{\rm T})\right ) .$$

- With the numerical values underlying here $10 \cdot \lg (E_{\rm B}/N_0) = 6 \ \rm dB$ and $\Delta \phi_{\rm T} = 30^\circ)$, the error probability of the BPSK (left diagram) increases from $p_{\rm B} \approx 0.2\%$ to about $p_{\rm B} \approx 0.6\%$.

- In contrast, for the 4–QAM (right diagram), the error probability increases almost by a factor of $40$ under the same conditions: $p_{\rm B} \approx 8\%$.

- If $|\Delta \phi_{\rm T}| < 45^\circ$, the following general equation holds for the 4–QAM (see Exercise 1.9 ):

- $$p_{\rm B} = 1/2 \cdot {\rm Q}\left ( \sqrt{\frac{2 \cdot E_{\rm B}}{N_0 }} \hspace{0.1cm}\cdot \frac{\cos(45^\circ)}{\cos(45^\circ+{\rm \Delta} \phi_{\rm T})}\right) + 1/2 \cdot {\rm Q}\left ( \sqrt{\frac{2 \cdot E_{\rm B}}{N_0 }} \hspace{0.1cm}\cdot \frac{\cos(45^\circ)}{\cos(45^\circ-{\rm \Delta} \phi_{\rm T})}\right).$$

$\text{Conclusion:}$

- Although 4–QAM can be used to transmit twice the information as BPSK over the same channel, under ideal conditions both systems have the same error probability.

- However, under non-ideal conditions – for example, when there is a phase offset – the error probability of 4–QAM increases much more than that of BPSK.

Baseband model for ASK and BPSK

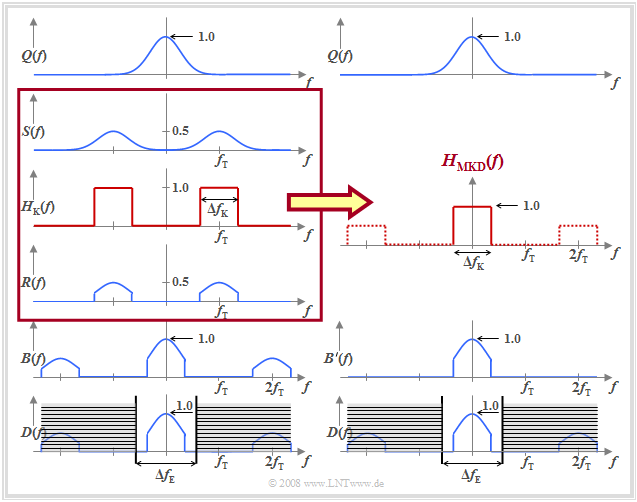

The diagram above shows again the overall block diagram of a carrier frequency system with coherent demodulation, which is valid for ASK (unipolar amplitude coefficients) and BPSK (bipolar coefficients) in the same way.

- Multiplication by the carrier signal $z(t)$ shifts the spectrum $Q(f)$ of the source signal – and accordingly the power-spectral density ${\it \Phi}_q(f)$ – on both sides by the carrier frequency $(\pm f_{\rm T})$.

- After the channel, this shift is reversed by the synchronous demodulator.

If one assumes the equivalent baseband model according to the diagram below, the calculation of the signals after the demodulator can be simplified:

- One virtually truncates the influence of modulator and demodulator and replaces the bandpass channel with the frequency response $H_{\rm K}(f)$ by a suitable lowpass transmission function $H_{\rm MKD}(f)$, where the index stands for "modulator–channel–demodulator" (Modulator–Kanal–Demodulator).

- Considering a phase difference $\Delta \phi_{\rm T}$ between the carrier signals of transmitter and receiver, we obtain for the resulting transmission function:

- $$H_{\rm MKD}(f) = {1}/{2} \cdot \big [ {\rm e}^{\hspace{0.04cm}-{\rm j} \hspace{0.04cm}\cdot \hspace{0.04cm}{\rm \Delta} \phi_{\rm T}} \cdot H_{\rm K}(f-f_{\rm T}) +{\rm e}^{\hspace{0.04cm}{\rm j} \hspace{0.04cm}\cdot \hspace{0.04cm}{\rm \Delta} \phi_{\rm T}} \cdot H_{\rm K}(f+f_{\rm T})\big ] .$$

- For a real channel frequency response $f_{\rm T}$ that is symmetric about the carrier frequency $H_{\rm K}(f)$ – that is, if $H_{\rm K}(f_{\rm T}-f) = H_{\rm K}(f_{\rm T}+f)$ – this equation can be simplified as follows:

- $$H_{\rm MKD}(f) = \frac{\cos({\rm \Delta} \phi_{\rm T})}{2} \cdot \big [ H_{\rm K}(f-f_{\rm T}) + H_{\rm K}(f+f_{\rm T})\big ] .$$

- Thus, the signals $b\hspace{0.08cm}'(t)$ in the lower image and $b(t)$ after the demodulator of the bandpass system in the upper image are identical except for the $±2f_{\rm T}$ components. However, these components are eliminated by the $H_{\rm E}(f)$ receiver filter and need not be considered further.

$\text{Conclusion:}$

- The error probabilities of ASK and BPSK can thus also be computed with the simpler baseband model, and even when a distorting channel $H_{\rm K}(f)$ is present.

- It should be noted that the noise signal $n(t)$ must also be transformed into the lowpass region. For white noise, ${\it \Phi}_n(f) = N_0/2$ must be replaced by ${\it \Phi}_{n,\hspace{0.06cm}{\rm TP} }(f) = N_0$ for this purpose.

$\text{Example 3:}$ The diagram illustrates the baseband model by means of the amplitude spectra, assuming for simplicity:

- a Gaussian $Q(f)$,

- the BPSK modulation,

- a rectangular bandpass channel $H_{\rm K}(f)$,

- a phase-synchronous demodulation, and

- a likewise rectangular receiver filter $H_{\rm E}(f)$ with $\Delta f_{\rm E} > \Delta f_{\rm K}$.

It can be seen:

- The spectrum $D(f)$ of the detection signal $d(t)$ is correctly reproduced by the equivalent baseband model, although the spectra $B(f)$ and $B\hspace{0.05cm}'(f)$, respectively, differ by twice the carrier frequency.

- The resulting transmission function $H_{\rm MKD}(f)$ also accounts for the band limitation due to the channel, which in this example was assumed to be rectangular around the carrier frequency.

Exercises for the chapter

Exercise 1.08: Comparison of ASK and BPSK

Exercise 1.08Z: BPSK Error Probability

Exercise 1.10: BPSK Baseband Model

Exercise 1.10Z: Gaussian Band-pass