Difference between revisions of "Mobile Communications/Distance Dependent Attenuation and Shading"

| (106 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | {{FirstPage}} | |

{{Header | {{Header | ||

| − | |Untermenü= | + | |Untermenü=Time-Variant Transmission Channels |

|Vorherige Seite= | |Vorherige Seite= | ||

| − | |Nächste Seite= | + | |Nächste Seite=Probability Density of Rayleigh Fading |

}} | }} | ||

| − | == | + | == # OVERVIEW OF THE FIRST MAIN CHAPTER # == |

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | + | The first main chapter deals with time-variant transmission channels, a property that is of great importance for mobile communication. The description is given throughout in the equivalent low-pass range. | |

| − | + | The chapter deals in detail with the following topics: | |

| − | + | #The »distance-dependent attenuation of a radio signal« and various »path loss models«, | |

| − | + | #the influence of »shadowing«, which can be modeled through »Lognormal fading''«, | |

| + | #the non-frequency selective »Rayleigh fading« for channels without »line of sight« $\rm (LoS)$, | ||

| + | #the consideration of the »Doppler effect« by the so-called »Jakes spectrum«, | ||

| + | #the non-frequency selective »Rice fading« for channels with direct path $($"line of sight$)$. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | == Physical description of the mobile communication channel == |

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | + | [[File:EN_Mob_T1_1_S1.png|right|frame|Example for a mobile radio scenario|class=fit]] | |

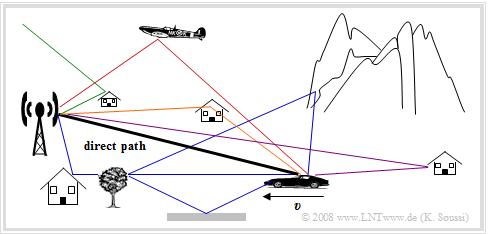

| + | The figure shows a typical mobile radio scenario with a fixed base station and a mobile subscriber moving towards the base station at the speed $v$ . | ||

| − | + | In this representation, the radio signal reaches the mobile station via a direct path. | |

| − | + | However, the antenna of the mobile subscriber also receives other signal components that reach the receiver in a detour, for example | |

| + | * due to reflections on houses, | ||

| + | * a mountain range, | ||

| + | * a plane, | ||

| + | * the ionosphere, | ||

| + | * the ground. | ||

| + | <br clear = all> | ||

| + | This scenario can be used to explain important problems in mobile communications: | ||

| + | *»'''Path Loss'''«: This measures the attenuation of the electromagnetic wave, which depends to a large extent on the distance between transmitter and receiver.<br> | ||

| − | + | *»'''Shadowing'''«: This describes a slow change in reception conditions due to the changing environment, for example when you pass a building or when you leave a wooded area.<br> | |

| − | :< | + | *»'''Multipath Propagation'''«: If the signal reaches the receiver on several paths with differences in propagation time, constructive or destructive superimpositions up to complete extinction occur, depending on the signal frequency. For certain frequencies the topology is favorable, for others unfavorable. Therefore this effect is also called <i>Frequency Selective Fading</i>. <br> |

| − | |||

| − | + | *»'''Time Variance'''«: The effect is caused by the movement of the transmitter and/or the receiver, because there is a different channel at each time. The transmission quality decreases rapidly if the direct path is shadowed by an obstacle. The received signal is then composed only of the partial signals arriving on detours, which are attenuated compared to the direct path due to scattering from trees and bushes and possibly refraction and diffraction phenomena, and which add vectorially to the total signal.<br> | |

| − | : | + | *»'''Doppler Effect'''«: Depending on whether (and also at what angle) the mobile station is moving towards or away from the transmitter, (slight) frequency shifts occur and thus statistical links within the received signal, which cause [[Digital_Signal_Transmission/Causes_and_Effects_of_Intersymbol_Interference#Definition_of_the_term_.22Intersymbol_Interference.22|$\text{intersymbol interference}$]] .<br><br> |

| − | |||

| − | + | In this chapter we will take a closer look at path loss and shadowing effects. The following chapters deal with time variance, also taking into account the Doppler effect. The second main chapter describes multipath propagation, which results in echoes in mobile radio.<br> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | == Free-space propagation == | |

| − | + | <br> | |

| + | One speaks of "free-space propagation" when there is a line of sight between the transmitter and the receiver positioned at a distance $d$ as in satellite communications or in space. The radio waves propagate in "empty space" unhindered spherically around the transmitting antenna, but are attenuated with increasing distance due to the energy conservation law.<br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Geometrically you can imagine that the radius $R$ of the sphere and thus also the spherical surface become larger and larger and at constant total energy the energy per unit area becomes proportional to $1/R^2$ smaller and smaller.<br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | We assume an unmodulated oscillation of the frequency $f_{\rm S}$ or of the wavelength $\lambda= c/f_{\rm S}$ where $c = 3 \cdot 10^8\ \rm m/s$ indicates the ''speed of light'' , the signal power is $P_{\rm S}$.<br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harald_T._Friis $\text{Harald Friis}$] gave an equation in 1944 for the received power $P_{\rm E}(d)$ from the distance $d$ (this equation, however, is only valid in a vacuum): | ||

| + | |||

| + | ::<math>P_{\rm E}(d) = \frac{P_{\rm S} \cdot G_{\rm S} \cdot G_{\rm E} \cdot \lambda^2}{16 \cdot \pi^2 \cdot d^2 \cdot V_{\rm add}} = | ||

| + | \frac{P_{\rm S} \cdot G_{\rm S} \cdot G_{\rm E} /V_{\rm add}}{K_{\rm FR}(d)} \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | *$G_{\rm S}$ and $G_{\rm E}$ indicate the antenna gains of transmitter and receiver, respectively. | ||

| + | *$V_{\rm add} > 1$ summarizes all additional losses independent of the wave propagation, e.g. through the antennas's cable feeds. | ||

| + | *The »'''free-space attenuation'''« $K_{\rm FR}(d)$ depends on the distance $d$ : | ||

| + | |||

| + | ::<math>K_{\rm FR}(d) = K_{\rm FR}(d_0) \cdot (d/d_0)^2 \hspace{0.2cm}{\rm with} \hspace{0.2cm} | ||

| + | K_{\rm FR}(d_0) = ({4 \pi d_0}/{\lambda} )^2 \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | ||

| − | + | Usually the free-space attenuation is specified logarithmically with the pseudo unit "dB". | |

| − | + | Then the power loss due to free-space attenuation $(V$ stands for "Verlust" (German) ⇒ "loss" in dB$)$: | |

| − | + | ::<math>V_{\rm FR}(d) = 10 \cdot {\rm lg} \hspace{0.1cm} K_{\rm FR}(d) = V_{\rm 0} + 20\,\,{\rm dB} \cdot {\rm lg} \hspace{0.1cm} (d/d_0)\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.5cm} V_{\rm 0} = V_{\rm FR}(d_0) = 20\,\,{\rm dB} \cdot {\rm lg} \hspace{0.2cm} ({4 \pi d_0}/{\lambda}) \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | |

| − | + | It should be noted about this equation: | |

| + | *The equation only applies in the far field of the antenna $(d > d_{\rm F})$. Here $d_{\rm F} = 2 D^2/\lambda$ the so-called »'''Fraunhofer distance'''«. For $D$ the largest physical dimension of the transmitting antenna must be used.<br> | ||

| − | + | *The equation does not apply to $d \to 0$. This would result in the limit value $K_{\rm FR} \to 0$, and it would result independently from $P_{\rm S}$ always an infinite received power $P_{\rm E}(d \to 0)$.<br> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | *The free-space attenuation $K_{\rm FR}(d)$ increases quadratically with increasing distance $d$ and also quadratically with increasing signal frequency $f_{\rm S}$, that is, with decreasing wavelength $\lambda$.<br> | |

| − | |||

| − | * | + | *For example, for $\text{GSM 1800}$ $(f_{\rm S} = 1.8 \ \rm GHz$ ⇒ $\lambda \approx 17 \ \rm cm)$: |

| + | :$$K_{\rm FR}(d = 1\ \rm km) = 1.6 \cdot 10^9.$$ | ||

| + | :The receiver at a distance of one kilometer does not receive even one billionth of the transmitting power.<br> | ||

| − | + | In the [[Aufgaben:Exercise 1.1Z: Simple Path Loss Model|"Exercise 1.1Z"]] the above Friis equation is to be numerically evaluated and interpreted. Usually, the free-space attenuation is set in relation to a suitable normalization distance $d_0$ ⇒ $K_{\rm FR}(d/d_0)$, where $d_0 = 1\ \rm m$ is often used.<br> | |

| − | + | == Common path loss model == | |

| + | <br> | ||

| + | In contrast to satellite and radio relay links, in the case of land mobile radio in addition to free-space attenuation, other disturbing effects must be taken into account which also contribute to a reduction in received power, namely: | ||

| + | *»'''Reflections'''«: By superimposing the transmitted signal with a signal component reflected on the ground or on other large smooth surfaces, cancellations can occur which cause a decrease in the received power up to the fourth power of the distance $d$ between transmitter and receiver. For more information, see [Zan05]<ref name = 'Zan05'>Zangl, J.: Multi-Hop-Netze mit Kanalcodierung und Medium Access Controll (MAC). Düsseldorf: VDI Verlag, Reihe 10, Nummer 761, 2005.</ref> and [PA95]<ref name = 'PA95'>Pahlavan, K.; Allen, L.: Wireless Information Networks. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Wiley Series in Telecommunications and Signal Processing, 1995.</ref>.<br> | ||

| − | :< | + | *»'''Diffraction'''«: This is when the signal is not reflected but deflected from its direction of propagation, for example at the edge of a building. A physical explanation can be found again in [Zan05]<ref name = 'Zan05'></ref>.<br> |

| − | + | *»'''Dispersion'''«: If the connection transmitter – receiver is interrupted by several objects with irregular surfaces (for example trees or bushes) the signal arrives at the receiver in the form of many scattered signals with slightly different propagation times. The size of the obstacle determines whether it is to be interpreted as a reflecting or as a scattering object.<br><br> | |

| − | + | The effects mentioned here are responsible for the fact that mobile radio can be operated without direct line of sight $\rm (LOS)$, and thus one of the bases for the economic success of mobile radio systems. Negatively, these effects are caused by a lower received power, which must be taken into account by a larger exponent than $\gamma = 2$ . We then no longer speak of "free-space attenuation", but generally of "path attenuation factor": | |

| − | : | ||

| − | + | ::<math>K_{\rm P}(d) = K_{\rm P}(d_0) \cdot (d/d_0)^\gamma \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The corresponding dB–magnitude we call the »'''path loss'''« $(\rm lg$ is the logarithm to the base $10)$: | |

| − | + | ::<math>V_{\rm P}(d) = V_{\rm 0} + \gamma \cdot 10\,{\rm dB} \cdot {\rm lg} \hspace{0.1cm} (d/d_0)\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.5cm} | |

| + | V_{\rm 0} = V_{\rm P}(d_0) = \gamma \cdot 10\,{\rm dB} \cdot {\rm lg} \hspace{0.1cm} \frac{4 \cdot \pi \cdot d_0}{\lambda}\hspace{0.05cm}. </math> | ||

| − | * | + | From these equations it can be seen that the free-space attenuation $V_{\rm FR}(d)$ is a special case of $V_{\rm P}(d)$ with $\gamma = 2$ . In [Zan05]<ref name = 'Zan05'></ref> numerical values are given for the exponent $\gamma$ which were determined as mean values over a large number of measurements. Among other things |

| + | *in clear view (satellite, radio relay): $\gamma \approx 2$,<br> | ||

| + | *in an urban setting: $\gamma = 2.7 \ \text{...} \ 3.5$,<br> | ||

| + | *in a shaded urban setting: $\gamma = 3.0\ \text{...} \ 5.0$,<br> | ||

| + | *inside buildings without a line of sight: $\gamma = 4.0 \ \text{...} \ 6.0$.<br> | ||

| − | == | + | == Other, more accurate path loss models == |

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | + | The relatively simple path loss model shown in the last section is well suited for macro cells, but requires high base station antennas. It was used, for example, as a reference–scenario for the standardization of [[Mobile_Communications/General information on the LTE mobile communications standard|$\text{Long Term Evolution}$]] $\rm (LTE)$.<br> | |

| − | + | Of course, this very simple two–parameter model $(V_0, \ \gamma)$ cannot reproduce all use cases with sufficient accuracy. A large number of other models for power attenuation can be found in the literature, which are more precisely adapted to specific boundary conditions (neighbourhood) and also take different cell sizes into account. Well-known are for example, see [Gol06]<ref name='Gol06'>Goldsmith, A.: Wireless Communications. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2006.</ref>: | |

| − | * | + | *the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hata_Model $\text{Okumura–Hata model}$],<br> |

| − | * | + | *the path loss model according to [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/COST_Hata_model $\text{COST 231}$],<br> |

| − | * | + | *the [https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8597901 $\text{Dual–slope model}$].<br><br> |

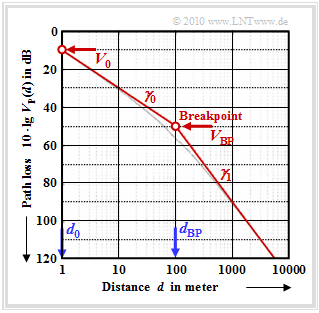

| − | + | [[File:EN_Mob_T1_1_S4.png|right|frame|Dual-slope path loss model]] | |

| + | {{GraueBox|TEXT= | ||

| + | $\text{Example 1:}$ The Dual–slope model is often used for simulations of micro cells in urban areas. The equation is the following, with the parameters $d_0 = 1\ \rm m$ und $d_{\rm BP}$ $($<i>Breakpoint</i>, for example $d_{\rm BP} = 100\ \rm m)$: | ||

| − | :<math>V_{\rm P}(d) = V_{\rm 0} + \gamma_0 \cdot 10\,{\rm dB} \cdot {\rm lg} \hspace{0. | + | ::<math>V_{\rm P}(d) \hspace{-0.05cm} = \hspace{-0.05cm} V_{\rm 0} \hspace{-0.05cm}+\hspace{-0.05cm} \gamma_0 \hspace{-0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{-0.05cm} 10\,{\rm dB} \hspace{-0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{-0.05cm}{\rm lg} \hspace{0.01cm} \left ( {d}/{d_0} \right ) |

| − | + (\gamma_1 - \gamma_0) \cdot 10\,{\rm dB} \cdot {\rm lg} \hspace{0. | + | \hspace{-0.05cm}+ \hspace{-0.05cm}(\gamma_1 \hspace{-0.05cm}- \hspace{-0.05cm}\gamma_0) \hspace{-0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{-0.05cm}10\,{\rm dB} \hspace{-0.05cm}\cdot\hspace{-0.05cm} {\rm lg} \hspace{0.01cm} \left (1+ {d}/{d_{\rm BP} } \right )\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> |

| − | + | The graph shows this curve for $V_{\rm 0} = 10 \ {\rm dB}$, $\gamma_0 = 2$ und $\gamma_1 = 4$ in the range from one meter to several kilometers (thin grey curve). | |

| − | + | To simplify matters, the asymptotic approximation shown in red in the graph is used | |

| − | + | ::<math>V_{\rm P}(d) = \left\{ \begin{array}{c} V_{\rm 0} + \gamma_0 \cdot 10\,{\rm dB} \cdot {\rm lg} \hspace{0.1cm} (d/d_0)\hspace{0.05cm},\\ | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | :<math>V_{\rm P}(d) = \left\{ \begin{array}{c} V_{\rm 0} + \gamma_0 \cdot 10\,{\rm dB} \cdot {\rm lg} \hspace{0.1cm} (d/d_0)\hspace{0.05cm},\\ | ||

V_{\rm BP} + \gamma_1 \cdot 10\,{\rm dB} \cdot {\rm lg} \hspace{0.1cm} (d/d_{\rm BP})\hspace{0.05cm}, \end{array} \right.\quad | V_{\rm BP} + \gamma_1 \cdot 10\,{\rm dB} \cdot {\rm lg} \hspace{0.1cm} (d/d_{\rm BP})\hspace{0.05cm}, \end{array} \right.\quad | ||

| − | \begin{array}{*{1}c} {\rm | + | \begin{array}{*{1}c} {\rm for} \hspace{0.15cm}d < d_{\rm BP}\hspace{0.05cm}, |

| − | \\ {\rm | + | \\ {\rm for} \hspace{0.15cm} d \ge d_{\rm BP}\hspace{0.05cm} \\ \end{array}</math> |

| − | + | The value $V_{\rm BP} = 50 \ {\rm dB}$ is derived from the equation for the first section at the border $d = 100\ \rm m$ of the scope.<br> | |

| − | < | + | <i>Note:</i> In the [[Aufgaben:Exercise 1.1: Dual Slope Loss Model|"Excercise 1.1"]] this model is still being examined in detail.}}<br> |

| − | == | + | == Additional loss due to shadowing == |

<br> | <br> | ||

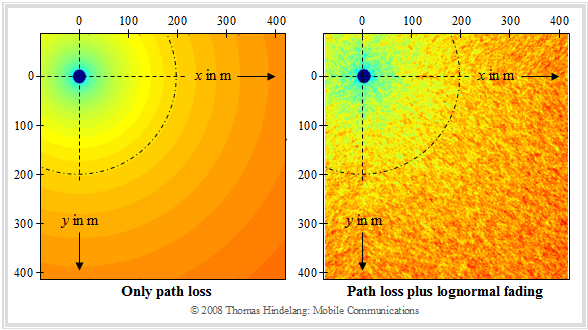

| − | + | The disturbing influence of shadowing is explained with the help of a graphic, taken from the lecture manuscript [Hin08]<ref name = 'Hin08'>Hindelang, T.: Mobile Communications. Lecture notes. Institute for Communications Engineering. Munich: Technical University of Munich, 2008.</ref>: | |

| + | [[File:EN_Mob_T1_1_S5.png|right|frame|Path loss without and with consideration of shading]] | ||

| − | + | *The previous path loss models only take into account the distance-dependent signal attenuation according to the left graph and disregard topological factors such as the influence of shading. | |

| − | + | *In land mobile radio, shadowing causes the signal level to vary even when moving at the same distance from the base station (on an arc of a circle) . | |

| − | * | + | |

| + | *This is shown in the right-hand graph, with darker areas indicating greater path loss. The difference between the left and right images is due to shadowing.<br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The effects of shadowing can be summarized as follows: | ||

| + | *For stationary transmitters and receivers, the shadowing is to be considered deterministic. It causes the path loss due to the shadowing to change by a constant value $V_{\rm S}$ (in dB): | ||

::<math>V_{\rm P}(d) = V_{\rm 0} + \gamma \cdot 10\,{\rm dB} \cdot {\rm lg} \hspace{0.1cm} (d/d_0)+ V_{\rm S}\hspace{0.05cm}. </math> | ::<math>V_{\rm P}(d) = V_{\rm 0} + \gamma \cdot 10\,{\rm dB} \cdot {\rm lg} \hspace{0.1cm} (d/d_0)+ V_{\rm S}\hspace{0.05cm}. </math> | ||

| − | * | + | *If the receiver (or the sender) moves, the <i>shadowing</i>–loss changes according to the coordinates and therefore also with time. This means: $V_{\rm S}$ ⇒ $V_{\rm S}(x, y)$ and $V_{\rm S}$ ⇒ $V_{\rm S}(t)$, respectively.<br> |

| + | |||

| − | + | However, such channel changes are very slow due to shading. Often the conditions remain the same for several seconds and one speaks here of "Long Term Fading" in contrast to fast fading like [[Mobile_Communications/Probability density of Rayleigh fading#A very general description of the mobile communication channel|$\text{Rayleigh fading}$]] and [[Mobile_Communications/Non-Frequency_Selective_Fading_With_Direct_Component#Channel_model_and_Rice_PDF|$\text{Rice fading}$]].<br> | |

| − | == | + | == Lognormal channel model== |

<br> | <br> | ||

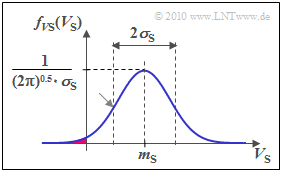

| − | + | [[File:EN_Mob_T1_1_S6.png|right|frame|Lognormal PDF ⇒ Shadowing loss]] | |

| + | To account for the loss $V_{\rm S}$ by shadowing, the system design must be based on statistical models that have emerged from empirical studies. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The best known is the »'''lognormal'''« channel model, which uses a [[Theory_of_Stochastic_Signals/Gaussian_Distributed_Random_Variables|$\text{Gaussian PDF}$]] for the random variable $V_{\rm S}$: | ||

| − | + | ::<math>f_{V_{\rm S}}(V_{\rm S}) = \frac {1}{ \sqrt{2 \pi }\cdot \sigma_{\rm S}} \cdot {\rm e }^{ - { (V_{\rm S}\hspace{0.05cm}- \hspace{0.05cm}m_{\rm S})^2}/(2 \hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm}\sigma_{\rm S}^2) } \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | |

| − | + | The name "lognormal" results from the fact that the dB–magnitude $V_{\rm S}$, which is derived from the linear power attenuation factor via the logarithm, is normally distributed (and thus Gaussian). <br> | |

| − | + | The lognormal channel model is determined by two parameters: | |

| + | *The mean value $m_{\rm S} = {\rm E}\big [V_{\rm S}\big ]$ gives the mean shadowing–loss. | ||

| + | *For rural areas it is usually calculated with $m_{\rm S} = 6 \ \rm dB$ and for urban areas it is assumed $m_{\rm S} =14 \ \rm dB$ ... $20 \ \rm dB$.<br> | ||

| − | + | *Also the standard deviation (or dispersion) $\sigma_{\rm S}$ is different for rural areas $(\approx 6 \ \rm dB)$ and for urban conditions $($between $8 \ \rm dB$ and $12 \ \rm dB)$ .<br><br> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Note that $V_{\rm S}$ can also take negative values when using lognormal fading (red area in the above graphic), which actually contradicts the idea of shading. In practice, however, this model has proven to be very good. | |

| − | + | The "gain by shading" could be interpreted as follows: | |

| − | *In | + | *In urban canyons, reflections from buildings can cause more energy to arrive than would be expected after losing the path.<br> |

| − | * | + | *The path loss exponent $\gamma$ is always fixed, for example $\gamma = 3.76$ in urban areas. But there are positions in the city where $\gamma$ is smaller.<br> |

| − | * | + | *Such a simple model cannot reproduce all the details exactly, so one should not try to interpret all the model properties physically.<br><br> |

| − | + | {{BlaueBox|TEXT= | |

| + | $\text{Conclusion:}$ It is useful to summarize the path loss portions in the following way: | ||

| − | :<math>V_{\rm P} = V_{\rm 1} + V_{\rm 2}(t) \hspace{0.25cm}{\rm | + | ::<math>V_{\rm P} = V_{\rm 1} + V_{\rm 2}(t) \hspace{0.25cm}{\rm with}\hspace{0.25cm} V_{\rm 1} = V_{\rm 0} + \gamma \cdot 10\,{\rm dB} \cdot {\rm lg} \hspace{0.1cm} (d/d_0)+ m_{\rm S}\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> |

| − | + | The second term $V_{\rm 2}(t)$ now describes a lognormal PDF with mean value zero: | |

| − | :<math>f_{ | + | ::<math>f_{V_2}(V_2) = \frac {1}{ \sqrt{2 \pi }\cdot \sigma_{\rm S} } \cdot {\rm e }^{ - V_2 ^2/(2 \hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm} \sigma_{\rm S}^2) }\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> |

| − | + | The distance dependency of $V_1$ does not play a major role and will not be further discussed here.}}<br> | |

| − | == | + | == Time domain model for lognormal fading== |

<br> | <br> | ||

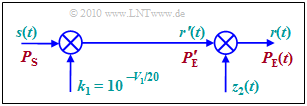

| − | [[File:P ID2099 Mob T 1 1 S6b v2.png| | + | [[File:P ID2099 Mob T 1 1 S6b v2.png|right|frame|Path loss model with lognormal fading]] |

| − | + | The figure shows a time domain model, with the help of which the path loss $V_{\rm P}$ can be simulated according to the above equation. Please note: | |

| + | *The input signal $s(t)$ possess the power $P_{\rm S}$. In logarithmic representation, the power is related to $1\ \rm mW$ and the pseudo unit "dBm" is added. | ||

| − | + | *The path loss $V_1$ is generated by multiplication with $k_1$. The output signal $r'(t)$ then has a power that is smaller by $V_1$ (in dB) : | |

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

::<math>k_1 = 10^{-V_{\rm 1}/20} \hspace{0.1cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.1cm} | ::<math>k_1 = 10^{-V_{\rm 1}/20} \hspace{0.1cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.1cm} | ||

| Line 182: | Line 219: | ||

10 \cdot {\rm lg} \hspace{0.1cm} \frac{P_{\rm S} }{\rm 1\,mW} - V_1 | 10 \cdot {\rm lg} \hspace{0.1cm} \frac{P_{\rm S} }{\rm 1\,mW} - V_1 | ||

\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | ||

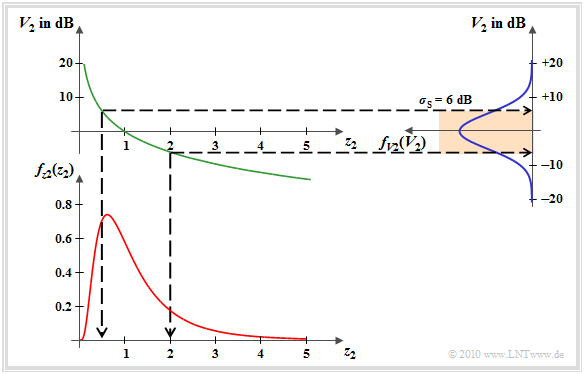

| + | [[File:P ID2102 Mob T 1 1 S6c v3.png|right|frame|Relation between Gaussian random variable $(V_2)$ and lognormal random variable $(z_2)$]] | ||

| + | *The (mean value-free) lognormal fading is simulated by multiplication with the random variable $z_2(t)$. | ||

| + | *The PDF results from the Gaussian random quantity $V_2$ by a [[Theory_of_Stochastic_Signals/Exponentially_Distributed_Random_Variables#Transformation_of_random_variables|$\text{nonlinear transformation}$]] at the characteristic curve | ||

| + | :$$z_2 = g(V_2) = 10^{-V_{\rm 2}/20}.$$ | ||

| − | * | + | *For $z_2< 0$ this PDF is zero, and for $z_2\ge 0$ applies with the abbreviation $C = \rm ln(10)/20 dB$: |

| − | + | :$$f_{z_{\rm 2}}(z_{\rm 2}) = \frac {{\rm e^{- {\rm ln}^2 (z_{\rm 2}) | |

| + | /({2 \hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm} C^2 \hspace{0.05cm} \cdot \hspace{0.05cm} \sigma_{\rm S}^2}) | ||

| + | } } }{ \sqrt{2 \pi }\cdot C \cdot \sigma_{\rm S} \cdot z_2} \hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| − | + | The graphic illustrates the transformation. You can see | |

| + | *the Gaussian PDF of $V_2$ (blue curve) with scatter $\sigma_{\rm S} = 6 \ \rm dB$, | ||

| + | *the negative logarithmic characteristic curve (green curve), and | ||

| + | *the asymmetric PDF (red curve) of $z_2(t)$ to be multiplied. | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | We refer here to the [[Aufgaben:Exercise 1.2Z: Lognormal Fading Revisited|"Exercise 1.2Z"]]. | |

| + | <br clear = all> | ||

| − | == | + | == Requirements for the following chapters == |

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | + | The average power of all signal components arriving at the receiver can be calculated using path loss and shading models. | |

| + | *The lognormal shadowing model takes into account slow changes of the reflectors due to the topology, with reception conditions changing only every five to ten meters in cities and every 30 to 100 meters in rural areas. | ||

| + | *In the following, the path loss and the influence of shadowing is not considered further, but normalized on $1$.<br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Paths can overlap constructively or destructively. The associated changes occur locally in the range of half the wavelength. In mobile radio, a few centimeters are enough to find completely different reception conditions. One speaks of »'''Fast Fading'''«. Such a channel is basically frequency–dependent and time–dependent. | ||

| + | |||

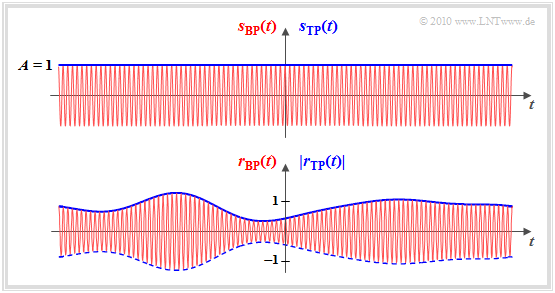

| + | [[File:P ID2100 Mob T 1 1 S7 v1.png|right|frame|Signals $s(t)$ and $r(t)$ for the description of the mobile radio channel in band-pass range (red) and in the equivalent low-pass range (blue); for the sketch $ϕ(t)\equiv 0$ ]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | For the rest of this first main chapter, frequency dependence is eliminated by assuming a single fixed frequency (see graph). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The following conditions therefore apply with immediate effect: | ||

| + | |||

| + | *The input signal of the mobile radio channel is a cosine oscillation with the amplitude $A = 1$ and the frequency $f_{\rm T}$. We refer to this harmonic oscillation as the "transmitted signal" $s_{\rm BP}(t)$. This band-pass signal is shown in red in the upper graphic.<br> | ||

| − | + | *The output signal $r_{\rm BP}(t)$ of the mobile radio channel – in the following called "received signal" – may differ from $s_{\rm BP}(t)$ both in amplitude (envelope) and in phase ⇒ lower graph, red.<br> | |

| − | + | *Furthermore, we mostly look at the mobile radio channel in the [[Signal_Representation/Equivalent_Low-Pass_Signal_and_its_Spectral_Function#Motivation_for_describing_in_the_equivalent_low-pass_range| $\text{equivalent low-pass range}$]]. (German: Tiefpass, $\rm TP$). The "transmitted signal" is then $s_{\rm TP}(t) = 1$ and thus real ⇒ blue horizontal in the upper graphic.<br> | |

| − | |||

| − | * | + | *The low-pass output signal $r_{\rm TP}(t)$ is generally complex, where the envelope is given by $a(t)$ and the phase $\phi(t)$ is noticeable by shifts in the zero crossings ⇒ blue envelope in the lower graph.<br><br> |

| − | + | {{BlaueBox|TEXT= | |

| + | $\text{Conclusion:}$ For the »'''physical signal at the output of the mobile radio channel'''« ⇒ »'''band-pass received signal'''« always applies in the following: | ||

| − | + | ::<math>r_{\rm BP}(t) = a(t) \cdot \cos \big [2\pi f_{\rm T} t + \phi(t)\big ]\hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} a(t) = \vert r_{\rm BP}(t)\vert\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} \phi(t) = {\rm arc}\hspace{0.15cm} r_{\rm BP}(t)\hspace{0.05cm}.</math>}} | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ==Exercises for the chapter == |

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | [[Aufgaben: | + | [[Aufgaben:Exercise_1.1:_Dual_Slope_Loss_Model]] |

| − | [[ | + | [[Aufgaben:Exercise 1.1Z: Simple Path Loss Model]] |

| − | [[Aufgaben:1.2 Lognormal | + | [[Aufgaben:Exercise 1.2: Lognormal Channel Model]] |

| − | [[ | + | [[Aufgaben:Exercise 1.2Z: Lognormal Fading Revisited]] |

| − | == | + | ==References== |

<references/> | <references/> | ||

Latest revision as of 15:23, 29 January 2023

Contents

- 1 # OVERVIEW OF THE FIRST MAIN CHAPTER #

- 2 Physical description of the mobile communication channel

- 3 Free-space propagation

- 4 Common path loss model

- 5 Other, more accurate path loss models

- 6 Additional loss due to shadowing

- 7 Lognormal channel model

- 8 Time domain model for lognormal fading

- 9 Requirements for the following chapters

- 10 Exercises for the chapter

- 11 References

# OVERVIEW OF THE FIRST MAIN CHAPTER #

The first main chapter deals with time-variant transmission channels, a property that is of great importance for mobile communication. The description is given throughout in the equivalent low-pass range.

The chapter deals in detail with the following topics:

- The »distance-dependent attenuation of a radio signal« and various »path loss models«,

- the influence of »shadowing«, which can be modeled through »Lognormal fading«,

- the non-frequency selective »Rayleigh fading« for channels without »line of sight« $\rm (LoS)$,

- the consideration of the »Doppler effect« by the so-called »Jakes spectrum«,

- the non-frequency selective »Rice fading« for channels with direct path $($"line of sight$)$.

Physical description of the mobile communication channel

The figure shows a typical mobile radio scenario with a fixed base station and a mobile subscriber moving towards the base station at the speed $v$ .

In this representation, the radio signal reaches the mobile station via a direct path.

However, the antenna of the mobile subscriber also receives other signal components that reach the receiver in a detour, for example

- due to reflections on houses,

- a mountain range,

- a plane,

- the ionosphere,

- the ground.

This scenario can be used to explain important problems in mobile communications:

- »Path Loss«: This measures the attenuation of the electromagnetic wave, which depends to a large extent on the distance between transmitter and receiver.

- »Shadowing«: This describes a slow change in reception conditions due to the changing environment, for example when you pass a building or when you leave a wooded area.

- »Multipath Propagation«: If the signal reaches the receiver on several paths with differences in propagation time, constructive or destructive superimpositions up to complete extinction occur, depending on the signal frequency. For certain frequencies the topology is favorable, for others unfavorable. Therefore this effect is also called Frequency Selective Fading.

- »Time Variance«: The effect is caused by the movement of the transmitter and/or the receiver, because there is a different channel at each time. The transmission quality decreases rapidly if the direct path is shadowed by an obstacle. The received signal is then composed only of the partial signals arriving on detours, which are attenuated compared to the direct path due to scattering from trees and bushes and possibly refraction and diffraction phenomena, and which add vectorially to the total signal.

- »Doppler Effect«: Depending on whether (and also at what angle) the mobile station is moving towards or away from the transmitter, (slight) frequency shifts occur and thus statistical links within the received signal, which cause $\text{intersymbol interference}$ .

In this chapter we will take a closer look at path loss and shadowing effects. The following chapters deal with time variance, also taking into account the Doppler effect. The second main chapter describes multipath propagation, which results in echoes in mobile radio.

Free-space propagation

One speaks of "free-space propagation" when there is a line of sight between the transmitter and the receiver positioned at a distance $d$ as in satellite communications or in space. The radio waves propagate in "empty space" unhindered spherically around the transmitting antenna, but are attenuated with increasing distance due to the energy conservation law.

Geometrically you can imagine that the radius $R$ of the sphere and thus also the spherical surface become larger and larger and at constant total energy the energy per unit area becomes proportional to $1/R^2$ smaller and smaller.

We assume an unmodulated oscillation of the frequency $f_{\rm S}$ or of the wavelength $\lambda= c/f_{\rm S}$ where $c = 3 \cdot 10^8\ \rm m/s$ indicates the speed of light , the signal power is $P_{\rm S}$.

$\text{Harald Friis}$ gave an equation in 1944 for the received power $P_{\rm E}(d)$ from the distance $d$ (this equation, however, is only valid in a vacuum):

- \[P_{\rm E}(d) = \frac{P_{\rm S} \cdot G_{\rm S} \cdot G_{\rm E} \cdot \lambda^2}{16 \cdot \pi^2 \cdot d^2 \cdot V_{\rm add}} = \frac{P_{\rm S} \cdot G_{\rm S} \cdot G_{\rm E} /V_{\rm add}}{K_{\rm FR}(d)} \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

- $G_{\rm S}$ and $G_{\rm E}$ indicate the antenna gains of transmitter and receiver, respectively.

- $V_{\rm add} > 1$ summarizes all additional losses independent of the wave propagation, e.g. through the antennas's cable feeds.

- The »free-space attenuation« $K_{\rm FR}(d)$ depends on the distance $d$ :

- \[K_{\rm FR}(d) = K_{\rm FR}(d_0) \cdot (d/d_0)^2 \hspace{0.2cm}{\rm with} \hspace{0.2cm} K_{\rm FR}(d_0) = ({4 \pi d_0}/{\lambda} )^2 \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

Usually the free-space attenuation is specified logarithmically with the pseudo unit "dB".

Then the power loss due to free-space attenuation $(V$ stands for "Verlust" (German) ⇒ "loss" in dB$)$:

- \[V_{\rm FR}(d) = 10 \cdot {\rm lg} \hspace{0.1cm} K_{\rm FR}(d) = V_{\rm 0} + 20\,\,{\rm dB} \cdot {\rm lg} \hspace{0.1cm} (d/d_0)\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.5cm} V_{\rm 0} = V_{\rm FR}(d_0) = 20\,\,{\rm dB} \cdot {\rm lg} \hspace{0.2cm} ({4 \pi d_0}/{\lambda}) \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

It should be noted about this equation:

- The equation only applies in the far field of the antenna $(d > d_{\rm F})$. Here $d_{\rm F} = 2 D^2/\lambda$ the so-called »Fraunhofer distance«. For $D$ the largest physical dimension of the transmitting antenna must be used.

- The equation does not apply to $d \to 0$. This would result in the limit value $K_{\rm FR} \to 0$, and it would result independently from $P_{\rm S}$ always an infinite received power $P_{\rm E}(d \to 0)$.

- The free-space attenuation $K_{\rm FR}(d)$ increases quadratically with increasing distance $d$ and also quadratically with increasing signal frequency $f_{\rm S}$, that is, with decreasing wavelength $\lambda$.

- For example, for $\text{GSM 1800}$ $(f_{\rm S} = 1.8 \ \rm GHz$ ⇒ $\lambda \approx 17 \ \rm cm)$:

- $$K_{\rm FR}(d = 1\ \rm km) = 1.6 \cdot 10^9.$$

- The receiver at a distance of one kilometer does not receive even one billionth of the transmitting power.

In the "Exercise 1.1Z" the above Friis equation is to be numerically evaluated and interpreted. Usually, the free-space attenuation is set in relation to a suitable normalization distance $d_0$ ⇒ $K_{\rm FR}(d/d_0)$, where $d_0 = 1\ \rm m$ is often used.

Common path loss model

In contrast to satellite and radio relay links, in the case of land mobile radio in addition to free-space attenuation, other disturbing effects must be taken into account which also contribute to a reduction in received power, namely:

- »Reflections«: By superimposing the transmitted signal with a signal component reflected on the ground or on other large smooth surfaces, cancellations can occur which cause a decrease in the received power up to the fourth power of the distance $d$ between transmitter and receiver. For more information, see [Zan05][1] and [PA95][2].

- »Diffraction«: This is when the signal is not reflected but deflected from its direction of propagation, for example at the edge of a building. A physical explanation can be found again in [Zan05][1].

- »Dispersion«: If the connection transmitter – receiver is interrupted by several objects with irregular surfaces (for example trees or bushes) the signal arrives at the receiver in the form of many scattered signals with slightly different propagation times. The size of the obstacle determines whether it is to be interpreted as a reflecting or as a scattering object.

The effects mentioned here are responsible for the fact that mobile radio can be operated without direct line of sight $\rm (LOS)$, and thus one of the bases for the economic success of mobile radio systems. Negatively, these effects are caused by a lower received power, which must be taken into account by a larger exponent than $\gamma = 2$ . We then no longer speak of "free-space attenuation", but generally of "path attenuation factor":

- \[K_{\rm P}(d) = K_{\rm P}(d_0) \cdot (d/d_0)^\gamma \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

The corresponding dB–magnitude we call the »path loss« $(\rm lg$ is the logarithm to the base $10)$:

- \[V_{\rm P}(d) = V_{\rm 0} + \gamma \cdot 10\,{\rm dB} \cdot {\rm lg} \hspace{0.1cm} (d/d_0)\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.5cm} V_{\rm 0} = V_{\rm P}(d_0) = \gamma \cdot 10\,{\rm dB} \cdot {\rm lg} \hspace{0.1cm} \frac{4 \cdot \pi \cdot d_0}{\lambda}\hspace{0.05cm}. \]

From these equations it can be seen that the free-space attenuation $V_{\rm FR}(d)$ is a special case of $V_{\rm P}(d)$ with $\gamma = 2$ . In [Zan05][1] numerical values are given for the exponent $\gamma$ which were determined as mean values over a large number of measurements. Among other things

- in clear view (satellite, radio relay): $\gamma \approx 2$,

- in an urban setting: $\gamma = 2.7 \ \text{...} \ 3.5$,

- in a shaded urban setting: $\gamma = 3.0\ \text{...} \ 5.0$,

- inside buildings without a line of sight: $\gamma = 4.0 \ \text{...} \ 6.0$.

Other, more accurate path loss models

The relatively simple path loss model shown in the last section is well suited for macro cells, but requires high base station antennas. It was used, for example, as a reference–scenario for the standardization of $\text{Long Term Evolution}$ $\rm (LTE)$.

Of course, this very simple two–parameter model $(V_0, \ \gamma)$ cannot reproduce all use cases with sufficient accuracy. A large number of other models for power attenuation can be found in the literature, which are more precisely adapted to specific boundary conditions (neighbourhood) and also take different cell sizes into account. Well-known are for example, see [Gol06][3]:

- the path loss model according to $\text{COST 231}$,

$\text{Example 1:}$ The Dual–slope model is often used for simulations of micro cells in urban areas. The equation is the following, with the parameters $d_0 = 1\ \rm m$ und $d_{\rm BP}$ $($Breakpoint, for example $d_{\rm BP} = 100\ \rm m)$:

- \[V_{\rm P}(d) \hspace{-0.05cm} = \hspace{-0.05cm} V_{\rm 0} \hspace{-0.05cm}+\hspace{-0.05cm} \gamma_0 \hspace{-0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{-0.05cm} 10\,{\rm dB} \hspace{-0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{-0.05cm}{\rm lg} \hspace{0.01cm} \left ( {d}/{d_0} \right ) \hspace{-0.05cm}+ \hspace{-0.05cm}(\gamma_1 \hspace{-0.05cm}- \hspace{-0.05cm}\gamma_0) \hspace{-0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{-0.05cm}10\,{\rm dB} \hspace{-0.05cm}\cdot\hspace{-0.05cm} {\rm lg} \hspace{0.01cm} \left (1+ {d}/{d_{\rm BP} } \right )\hspace{0.05cm}.\]

The graph shows this curve for $V_{\rm 0} = 10 \ {\rm dB}$, $\gamma_0 = 2$ und $\gamma_1 = 4$ in the range from one meter to several kilometers (thin grey curve).

To simplify matters, the asymptotic approximation shown in red in the graph is used

- \[V_{\rm P}(d) = \left\{ \begin{array}{c} V_{\rm 0} + \gamma_0 \cdot 10\,{\rm dB} \cdot {\rm lg} \hspace{0.1cm} (d/d_0)\hspace{0.05cm},\\ V_{\rm BP} + \gamma_1 \cdot 10\,{\rm dB} \cdot {\rm lg} \hspace{0.1cm} (d/d_{\rm BP})\hspace{0.05cm}, \end{array} \right.\quad \begin{array}{*{1}c} {\rm for} \hspace{0.15cm}d < d_{\rm BP}\hspace{0.05cm}, \\ {\rm for} \hspace{0.15cm} d \ge d_{\rm BP}\hspace{0.05cm} \\ \end{array}\]

The value $V_{\rm BP} = 50 \ {\rm dB}$ is derived from the equation for the first section at the border $d = 100\ \rm m$ of the scope.

Note: In the "Excercise 1.1" this model is still being examined in detail.

Additional loss due to shadowing

The disturbing influence of shadowing is explained with the help of a graphic, taken from the lecture manuscript [Hin08][4]:

- The previous path loss models only take into account the distance-dependent signal attenuation according to the left graph and disregard topological factors such as the influence of shading.

- In land mobile radio, shadowing causes the signal level to vary even when moving at the same distance from the base station (on an arc of a circle) .

- This is shown in the right-hand graph, with darker areas indicating greater path loss. The difference between the left and right images is due to shadowing.

The effects of shadowing can be summarized as follows:

- For stationary transmitters and receivers, the shadowing is to be considered deterministic. It causes the path loss due to the shadowing to change by a constant value $V_{\rm S}$ (in dB):

- \[V_{\rm P}(d) = V_{\rm 0} + \gamma \cdot 10\,{\rm dB} \cdot {\rm lg} \hspace{0.1cm} (d/d_0)+ V_{\rm S}\hspace{0.05cm}. \]

- If the receiver (or the sender) moves, the shadowing–loss changes according to the coordinates and therefore also with time. This means: $V_{\rm S}$ ⇒ $V_{\rm S}(x, y)$ and $V_{\rm S}$ ⇒ $V_{\rm S}(t)$, respectively.

However, such channel changes are very slow due to shading. Often the conditions remain the same for several seconds and one speaks here of "Long Term Fading" in contrast to fast fading like $\text{Rayleigh fading}$ and $\text{Rice fading}$.

Lognormal channel model

To account for the loss $V_{\rm S}$ by shadowing, the system design must be based on statistical models that have emerged from empirical studies.

The best known is the »lognormal« channel model, which uses a $\text{Gaussian PDF}$ for the random variable $V_{\rm S}$:

- \[f_{V_{\rm S}}(V_{\rm S}) = \frac {1}{ \sqrt{2 \pi }\cdot \sigma_{\rm S}} \cdot {\rm e }^{ - { (V_{\rm S}\hspace{0.05cm}- \hspace{0.05cm}m_{\rm S})^2}/(2 \hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm}\sigma_{\rm S}^2) } \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

The name "lognormal" results from the fact that the dB–magnitude $V_{\rm S}$, which is derived from the linear power attenuation factor via the logarithm, is normally distributed (and thus Gaussian).

The lognormal channel model is determined by two parameters:

- The mean value $m_{\rm S} = {\rm E}\big [V_{\rm S}\big ]$ gives the mean shadowing–loss.

- For rural areas it is usually calculated with $m_{\rm S} = 6 \ \rm dB$ and for urban areas it is assumed $m_{\rm S} =14 \ \rm dB$ ... $20 \ \rm dB$.

- Also the standard deviation (or dispersion) $\sigma_{\rm S}$ is different for rural areas $(\approx 6 \ \rm dB)$ and for urban conditions $($between $8 \ \rm dB$ and $12 \ \rm dB)$ .

Note that $V_{\rm S}$ can also take negative values when using lognormal fading (red area in the above graphic), which actually contradicts the idea of shading. In practice, however, this model has proven to be very good.

The "gain by shading" could be interpreted as follows:

- In urban canyons, reflections from buildings can cause more energy to arrive than would be expected after losing the path.

- The path loss exponent $\gamma$ is always fixed, for example $\gamma = 3.76$ in urban areas. But there are positions in the city where $\gamma$ is smaller.

- Such a simple model cannot reproduce all the details exactly, so one should not try to interpret all the model properties physically.

$\text{Conclusion:}$ It is useful to summarize the path loss portions in the following way:

- \[V_{\rm P} = V_{\rm 1} + V_{\rm 2}(t) \hspace{0.25cm}{\rm with}\hspace{0.25cm} V_{\rm 1} = V_{\rm 0} + \gamma \cdot 10\,{\rm dB} \cdot {\rm lg} \hspace{0.1cm} (d/d_0)+ m_{\rm S}\hspace{0.05cm}.\]

The second term $V_{\rm 2}(t)$ now describes a lognormal PDF with mean value zero:

- \[f_{V_2}(V_2) = \frac {1}{ \sqrt{2 \pi }\cdot \sigma_{\rm S} } \cdot {\rm e }^{ - V_2 ^2/(2 \hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm} \sigma_{\rm S}^2) }\hspace{0.05cm}.\]

The distance dependency of $V_1$ does not play a major role and will not be further discussed here.

Time domain model for lognormal fading

The figure shows a time domain model, with the help of which the path loss $V_{\rm P}$ can be simulated according to the above equation. Please note:

- The input signal $s(t)$ possess the power $P_{\rm S}$. In logarithmic representation, the power is related to $1\ \rm mW$ and the pseudo unit "dBm" is added.

- The path loss $V_1$ is generated by multiplication with $k_1$. The output signal $r'(t)$ then has a power that is smaller by $V_1$ (in dB) :

- \[k_1 = 10^{-V_{\rm 1}/20} \hspace{0.1cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.1cm} 10 \cdot {\rm lg} \hspace{0.1cm} \frac{P_{\rm E}\hspace{0.05cm}' }{\rm 1\,mW}= 10 \cdot {\rm lg} \hspace{0.1cm} \frac{P_{\rm S} }{\rm 1\,mW} + 20 \cdot {\rm lg} \hspace{0.1cm} k_1 = 10 \cdot {\rm lg} \hspace{0.1cm} \frac{P_{\rm S} }{\rm 1\,mW} - V_1 \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

- The (mean value-free) lognormal fading is simulated by multiplication with the random variable $z_2(t)$.

- The PDF results from the Gaussian random quantity $V_2$ by a $\text{nonlinear transformation}$ at the characteristic curve

- $$z_2 = g(V_2) = 10^{-V_{\rm 2}/20}.$$

- For $z_2< 0$ this PDF is zero, and for $z_2\ge 0$ applies with the abbreviation $C = \rm ln(10)/20 dB$:

- $$f_{z_{\rm 2}}(z_{\rm 2}) = \frac {{\rm e^{- {\rm ln}^2 (z_{\rm 2}) /({2 \hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm} C^2 \hspace{0.05cm} \cdot \hspace{0.05cm} \sigma_{\rm S}^2}) } } }{ \sqrt{2 \pi }\cdot C \cdot \sigma_{\rm S} \cdot z_2} \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

The graphic illustrates the transformation. You can see

- the Gaussian PDF of $V_2$ (blue curve) with scatter $\sigma_{\rm S} = 6 \ \rm dB$,

- the negative logarithmic characteristic curve (green curve), and

- the asymmetric PDF (red curve) of $z_2(t)$ to be multiplied.

We refer here to the "Exercise 1.2Z".

Requirements for the following chapters

The average power of all signal components arriving at the receiver can be calculated using path loss and shading models.

- The lognormal shadowing model takes into account slow changes of the reflectors due to the topology, with reception conditions changing only every five to ten meters in cities and every 30 to 100 meters in rural areas.

- In the following, the path loss and the influence of shadowing is not considered further, but normalized on $1$.

Paths can overlap constructively or destructively. The associated changes occur locally in the range of half the wavelength. In mobile radio, a few centimeters are enough to find completely different reception conditions. One speaks of »Fast Fading«. Such a channel is basically frequency–dependent and time–dependent.

For the rest of this first main chapter, frequency dependence is eliminated by assuming a single fixed frequency (see graph).

The following conditions therefore apply with immediate effect:

- The input signal of the mobile radio channel is a cosine oscillation with the amplitude $A = 1$ and the frequency $f_{\rm T}$. We refer to this harmonic oscillation as the "transmitted signal" $s_{\rm BP}(t)$. This band-pass signal is shown in red in the upper graphic.

- The output signal $r_{\rm BP}(t)$ of the mobile radio channel – in the following called "received signal" – may differ from $s_{\rm BP}(t)$ both in amplitude (envelope) and in phase ⇒ lower graph, red.

- Furthermore, we mostly look at the mobile radio channel in the $\text{equivalent low-pass range}$. (German: Tiefpass, $\rm TP$). The "transmitted signal" is then $s_{\rm TP}(t) = 1$ and thus real ⇒ blue horizontal in the upper graphic.

- The low-pass output signal $r_{\rm TP}(t)$ is generally complex, where the envelope is given by $a(t)$ and the phase $\phi(t)$ is noticeable by shifts in the zero crossings ⇒ blue envelope in the lower graph.

$\text{Conclusion:}$ For the »physical signal at the output of the mobile radio channel« ⇒ »band-pass received signal« always applies in the following:

- \[r_{\rm BP}(t) = a(t) \cdot \cos \big [2\pi f_{\rm T} t + \phi(t)\big ]\hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} a(t) = \vert r_{\rm BP}(t)\vert\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} \phi(t) = {\rm arc}\hspace{0.15cm} r_{\rm BP}(t)\hspace{0.05cm}.\]

Exercises for the chapter

Exercise 1.1: Dual Slope Loss Model

Exercise 1.1Z: Simple Path Loss Model

Exercise 1.2: Lognormal Channel Model

Exercise 1.2Z: Lognormal Fading Revisited

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Zangl, J.: Multi-Hop-Netze mit Kanalcodierung und Medium Access Controll (MAC). Düsseldorf: VDI Verlag, Reihe 10, Nummer 761, 2005.

- ↑ Pahlavan, K.; Allen, L.: Wireless Information Networks. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Wiley Series in Telecommunications and Signal Processing, 1995.

- ↑ Goldsmith, A.: Wireless Communications. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2006.

- ↑ Hindelang, T.: Mobile Communications. Lecture notes. Institute for Communications Engineering. Munich: Technical University of Munich, 2008.