Difference between revisions of "Modulation Methods/Frequency Modulation (FM)"

m |

m |

||

| Line 131: | Line 131: | ||

| − | ==WM spectrum | + | ==WM spectrum of a harmonic oscillation== |

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | + | Now we assume a harmonic oscillation with phase $ϕ_{\rm N}$ for the source signal in general: | |

:$$q(t) = A_{\rm N} \cdot \cos \hspace{-0.1cm} \big[2 \pi f_{\rm N} \cdot t + \phi_{\rm N}\big ].$$ | :$$q(t) = A_{\rm N} \cdot \cos \hspace{-0.1cm} \big[2 \pi f_{\rm N} \cdot t + \phi_{\rm N}\big ].$$ | ||

| − | + | We are interested in the spectral function $S(f)$. For simplicity, the following will consider the magnitude spectrum $|S_+(f)|$ of the analytical signal, from which $|S(f)|$ can be derived in the familiar way. | |

| − | + | For any of the types of angle modulation described here – whether it is phase or frequency modulation – and regardless of the phase $ϕ_{\rm N}$ of the source signal, the following holds: | |

:$$|S_{\rm +}(f)| = A_{\rm T} \cdot \sum_{n = - \infty}^{+\infty}|{\rm J}_n (\eta)| \cdot \delta \big[f - (f_{\rm T} + n \cdot f_{\rm N})\big]\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | :$$|S_{\rm +}(f)| = A_{\rm T} \cdot \sum_{n = - \infty}^{+\infty}|{\rm J}_n (\eta)| \cdot \delta \big[f - (f_{\rm T} + n \cdot f_{\rm N})\big]\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| − | + | This equation can be explained as follows: | |

| − | * | + | *On the page [[Modulation_Methods/Phasenmodulation_(PM)#.C3.84quivalentes_TP.E2.80.93Signal_bei_Phasenmodulation|Äquivalentes TP-Signal bei PM]] wurde diese Gleichung für ein phasenmoduliertes Sinussignal abgeleitet, wobei $η = A_{\rm N} · K_{\rm PM}$ den Modulationsindex bezeichnet und ${\rm J}_n(η)$ die Besselfunkton erster Art und $n$–ter Ordnung. $K_{\rm PM}$ ist die Modulatorkonstante. |

*Durch eine andere Nachrichtenphase $ϕ_{\rm N}$ ändert sich nur die Phasenfunktion ${\rm arc} \ S_+(f)$, nicht aber das Betragsspektrum $|S_+(f)|$. Dieses wichtige Ergebnis wurde auch durch die [[Aufgaben:3.3Z_Kenngrößenbestimmung|Aufgabe 3.3Z]] bestätigt. | *Durch eine andere Nachrichtenphase $ϕ_{\rm N}$ ändert sich nur die Phasenfunktion ${\rm arc} \ S_+(f)$, nicht aber das Betragsspektrum $|S_+(f)|$. Dieses wichtige Ergebnis wurde auch durch die [[Aufgaben:3.3Z_Kenngrößenbestimmung|Aufgabe 3.3Z]] bestätigt. | ||

*Auf der Seite [[Modulation_Methods/Frequenzmodulation_(FM)#Frequenzmodulation_eines_Cosinussignals|Frequenzmodulation eines Cosinussignals]] wurde gezeigt, dass ein FM–Signal in gleicher Weise wie ein PM–Signal dargestellt werden kann, wenn der Modulationsindex $η = K_{\rm FM} · A_{\rm N}/ω_{\rm N}$ verwendet wird. Folgerichtig sind auch die Betragsspektren bei Phasen- und Frequenzmodulation in gleicher Form darstellbar. | *Auf der Seite [[Modulation_Methods/Frequenzmodulation_(FM)#Frequenzmodulation_eines_Cosinussignals|Frequenzmodulation eines Cosinussignals]] wurde gezeigt, dass ein FM–Signal in gleicher Weise wie ein PM–Signal dargestellt werden kann, wenn der Modulationsindex $η = K_{\rm FM} · A_{\rm N}/ω_{\rm N}$ verwendet wird. Folgerichtig sind auch die Betragsspektren bei Phasen- und Frequenzmodulation in gleicher Form darstellbar. | ||

Revision as of 18:20, 15 March 2022

Contents

- 1 Instantaneous frequency

- 2 Signal characteristics with frequency modulation

- 3 Frequency modulation of a cosine signal

- 4 WM spectrum of a harmonic oscillation

- 5 Einfluss einer Bandbegrenzung bei Winkelmodulation

- 6 Realisierung eines FM–Modulators

- 7 PLL–Realisierung eines FM–Demodulators

- 8 Aufgaben zum Kapitel

- 9 Quellenverzeichnis

Instantaneous frequency

We will once again assume an angle-modulated signal:

- $$s(t) = A_{\rm T} \cdot \cos \big[\psi(t)\big].$$

All the information about the source signal $q(t)$

- is thus exclusively captured by the angular function $ψ(t)$ ,

- while the envelope $a(t) = A_{\rm T}$ is constant.

$\text{Definitions:}$

- The instantaneous angular frequency is the derivative of the angular function with respect to time:

- $$\omega_{\rm A}(t) = \frac{ {\rm d}\psi(t)}{ {\rm d}t}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- Accordingly, the instantaneous frequency is described by:

- $$f_{\rm A}(t) = \frac{\omega_{\rm A}(t)}{2\pi} = \frac{1}{2\pi} \cdot \frac{ {\rm d}\hspace{0.03cm}\psi(t)}{ {\rm d}t}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- The frequency deviation is the maximum deviation $Δf_{\rm A}$ of the time-dependent instantaneous frequency $f_{\rm A}(t)$ from the constant carrier frequency $f_{\rm T}$.

For an angle modulation with carrier frequency $f_{\rm T}$ , the instantaneous frequency oscillates in the range

- $$f_{\rm T} - \Delta f_{\rm A} \le f_{\rm A}(t) \le f_{\rm T} + \Delta f_{\rm A}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

It should be emphasized that there is a fundamental difference between the instantaneous frequency $f_{\rm A}(t)$ and the spectrum $S(f)$ of an angle-modulated signal $s(t)$ that can be measured with a spectrum analyzer, as illustrated by the following example.

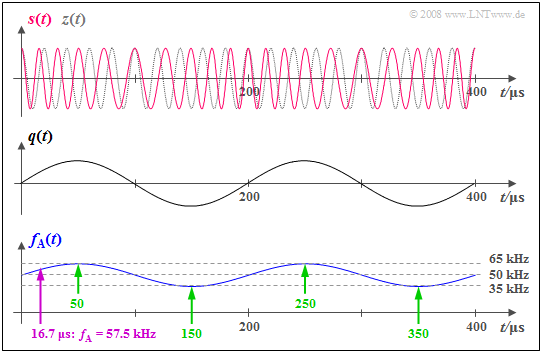

$\text{Example 1:}$ The graph shows the phase-modulated signal

- $$s(t) = A_{\rm T} \cdot \cos \hspace{-0.1cm} \big[\psi(t)\big] = A_{\rm T} \cdot \cos \hspace{-0.1cm} \big[2 \pi f_{\rm T} \hspace{0.05cm}t + \eta \cdot \sin (2 \pi f_{\rm N} \hspace{0.05cm} t)\big]$$

as well as the instantaneous frequency plotted beneath

- $$f_{\rm A}(t) = \frac{1}{2 \pi} \cdot \frac{ {\rm d}\hspace{0.03cm}\psi(t)}{ {\rm d}t} = f_{\rm T} + \Delta f_{\rm A}\cdot \cos (2 \pi f_{\rm N} \hspace{0.05cm} t) \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

Here, the system parameters are:

- $f_{\rm T} = 50 \ \rm kHz$,

- $f_{\rm N} = 5 \ \rm kHz$,

- $η = 3$.

From this, we derive the frequency deviation

- $Δf_{\rm A} = η · f_{\rm N} = 15 \ \rm kHz$.

In the middle, the qualitative progression of the sinusoidal source signal $q(t)$ is sketched for reference.

From these graphs, one can see:

- The instantaneous frequency $f_{\rm A}(t)$ can take on arbitrary values between $f_{\rm T} + Δf_{\rm A} = 65 \ \rm kHz$ $($at $t = 50\ \rm µ s,\ 250 \ µ s$, etc.$)$ and $f_{\rm T} \ – Δf_{\rm A} = 35 \ \rm kHz$ $($at $t = 150\ \rm µ s, \ 350 \ µ s$, etc.$)$ (see green marks).

- At time $t ≈ 16.7 \ \rm µ s$ , for example, $f_{\rm A}(t) = 57.5 \ \rm kHz$ holds (purple arrow).

- In contrast, the spectral function $S(f)$ consists of discrete Bessel lines at the frequencies ... , $30,\ 35,\ 40,\ 45,\ \mathbf{50},\ 55,\ 60,\ 65,\ 70$, ... $($each in $\rm kHz)$.

- There is no spectral line at $f = 57.5 \ \rm kHz$ , though there is one at $f = 70 \ \rm kHz$.

- In contrast, at no time does $f_{\rm A}(t) = 70 \ \rm kHz$ hold.

$\text{Therefore:}$

The instantaneous frequency $f_{\rm A}(t)$ is thus not a physically measurable frequency in the conventional sense, but only an abstract mathematical quantity, namely the derivative of the angular function $ψ(t)$.

Signal characteristics with frequency modulation

As in the chapter Phase Modulation we will assume that the carrier signal $z(t)$ has a cosine waveform and the source signal $q(t)$ is peak-limited.

$\text{Definition:}$ In a communication system, if the instantaneous angular frequency $ω_{\rm A}(t)$ is linearly dependent on the instantaneous value of the source signal $q(t)$, we call this frequency modulation $\rm (FM)$:

- $$\omega_{\rm A}(t) = 2 \pi \cdot f_{\rm A}(t) = \omega_{\rm T} + K_{\rm FM} \cdot q(t) \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

Here, $K_{\rm FM}$ denotes a dimensionally restricted constant. If $q(t)$ represents a voltage waveform, $K_{\rm FM}$ has the unit $\rm V^{–1}s^{–1}$.

In frequency modulation, the angular function $\psi(t)$ and the modulated signal $s(t)$ are given by:

- $$\psi(t) = \omega_{\rm T} \cdot t + K_{\rm FM} \cdot \int q(t)\hspace{0.1cm}{\rm d}t \hspace{0.05cm}\hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}s(t) = A_{\rm T} \cdot \cos \big[\psi(t)\big] \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

From this equation, we can immediately see:

- Even in the case of frequency modulation, the equivalent low-pass signal moves on an arc because of the constant envelope ⇒ $a(t) = A_{\rm T}$ .

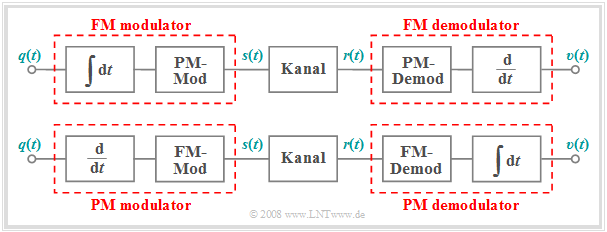

- A frequency modulator can be implemented using an integrator and a phase modulator. Consequently, the FM demodulator consists of a PM demodulator and a differentiator, as shown in the upper part of the following diagram.

The lower graph shows the inverse relationship ⇒ a possible description of a PM modulator and demodulator in terms of corresponding FM components.

It can also be seen from the above equation, that the equation encountered earlier on page A very simple (though unfortunately not always correct) modulator equation in the first chapter of this book, will only hold for frequency modulation in very special cases.

In frequency modulation, the conversion

- $$s(t) = a(t) \cdot \cos (\omega (t) \cdot t + \phi(t)) \hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} s(t) = A_{\rm T} \cdot \cos (\omega (t) \cdot t + \phi_{\rm T})$$

ist only allowed sometimes, such as in the nonlinear digital modulation method "Frequency Shift Keying" $\rm (FSK)$ with a right-angled fundamental pulse.

Frequency modulation of a cosine signal

For a cosine source signal $q(t)$ with frequency modulation, the instantaneous angular frequency is:

- $$q(t) = A_{\rm N} \cdot \cos (\omega_{\rm N} \cdot t)\hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} \omega_{\rm A}(t) = \omega_{\rm T} + K_{\rm FM} \cdot A_{\rm N} \cdot \cos(\omega_{\rm N} \cdot t)\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

Integrating this over time, we get the angular function:

- $$\psi(t) = \omega_{\rm T} \cdot t + \frac {K_{\rm FM} \cdot A_{\rm N}}{\omega_{\rm N}} \cdot \sin (\omega_{\rm N} \cdot t) \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

A comparison with the propositions in the chapter Phase Modulation makes clear:

- The frequency modulation of a cosine signal yields a qualitatively identical transmitted signal $s(t)$ as the phase modulation of a sinusoidal source signal $q(t)$.

- However, this requires that the modulator constants are matched according to the ratio $K_{\rm FM}/K_{\rm PM} = ω_{\rm N}$ .

- The transmitted signal $s(t)$ can thus be described uniformly for the two configurations "PM – sine signal" as well as "FM – cosine signal":

- $$s(t) = A_{\rm T} \cdot \cos \hspace{-0.1cm} \big[\omega_{\rm T} \cdot t + \eta \cdot \sin (\omega_{\rm N} \cdot t)\big] \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- However, when using this equation for the modulation index $η$ different equations must be use for phase and frequency modulation:

- $$\eta_{\rm PM} = {K_{\rm PM} \cdot A_{\rm N}},$$

- $$\eta_{\rm FM} = \frac {K_{\rm FM} \cdot A_{\rm N}}{\omega_{\rm N}} \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- If the source signal is not a harmonic oscillation, but is instead composed of several frequencies, the time signals also differ qualitatively for phase and frequency modulation. This can be seen in the earlier comparison of PSK and FSK.

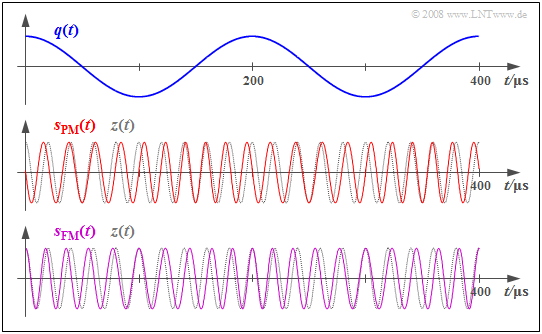

$\text{Example 2:}$ We will now assume a cosine source signal $q(t)$ with amplitude $A_{\rm N} = 3 \ \rm V$ and frequency $f_{\rm N} = 5 \ \rm kHz$ and consider the signal characteristics of phase modulation $\rm (PM)$ and frequency modulation $\rm (FM)$ with the same modulation index $η = 1.5$.

Thee middle graph shows the phase-modulated signal (rote curve) for the modulator parameters $f_{\rm T} = 50 \ \rm kHz$ und $K_{\rm PM} = \rm 0.5 V^{–1}$:

- $$s_{\rm PM}(t) = A_{\rm T} \cdot \cos \hspace{-0.1cm} \big[\omega_{\rm T} \cdot t + \eta \cdot \cos (\omega_{\rm N} \cdot t)\big ] \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- In phase modulation, $A_{\rm N} = 3 \ \rm V$ yields $η = 1.5 ≈ π/2$ for the phase deviation (modulation index).

- The maximum deviation of the zero crossings from their (equidistant) nominal positions is about a quarter of the carrier period.

- If the source signal is $q(t) > 0$, the zero crossings arrive early, and if $q(t) < 0$ , they come late.

The lower graph shows the frequency-modulated signal with the same modulation index $η$:

- $$s_{\rm FM}(t) = A_{\rm T} \cdot \cos \hspace{-0.1cm} \big[\omega_{\rm T} \cdot t + \eta \cdot \sin (\omega_{\rm N} \cdot t)\big ] \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

In this case, $η = 1.5$ is achieved by the modulator constant

- $$K_{\rm FM} = \frac {\eta \cdot \omega_{\rm N} }{A_{\rm N} } = {K_{\rm PM} \cdot \omega_{\rm N} } $$

- $$\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} K_{\rm FM} = 0.5\,{\rm V}^{-1} \cdot 2 \pi \cdot 5\,{\rm kHz} = 15708\,{\rm V}^{-1}{\rm s}^{-1} \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- Here, the frequency deviation is $Δf_{\rm A} = η · f_{\rm N} = 7.5 \ \rm kHz$, and instantaneous frequencies occur between $f_{\rm T}-Δf_{\rm A} = 42.5$ and $f_{\rm T}+Δf_{\rm A} =57.5 \ \rm kHz$ .

- the zero crossings now match those of the carrier signal $z(t)$ at the maxima and minima of the source signal $q(t)$ , while the maximum phase deviations can be seen at the zero crossings of $q(t)$ . The exact opposite is the case in phase modulation.

WM spectrum of a harmonic oscillation

Now we assume a harmonic oscillation with phase $ϕ_{\rm N}$ for the source signal in general:

- $$q(t) = A_{\rm N} \cdot \cos \hspace{-0.1cm} \big[2 \pi f_{\rm N} \cdot t + \phi_{\rm N}\big ].$$

We are interested in the spectral function $S(f)$. For simplicity, the following will consider the magnitude spectrum $|S_+(f)|$ of the analytical signal, from which $|S(f)|$ can be derived in the familiar way.

For any of the types of angle modulation described here – whether it is phase or frequency modulation – and regardless of the phase $ϕ_{\rm N}$ of the source signal, the following holds:

- $$|S_{\rm +}(f)| = A_{\rm T} \cdot \sum_{n = - \infty}^{+\infty}|{\rm J}_n (\eta)| \cdot \delta \big[f - (f_{\rm T} + n \cdot f_{\rm N})\big]\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

This equation can be explained as follows:

- On the page Äquivalentes TP-Signal bei PM wurde diese Gleichung für ein phasenmoduliertes Sinussignal abgeleitet, wobei $η = A_{\rm N} · K_{\rm PM}$ den Modulationsindex bezeichnet und ${\rm J}_n(η)$ die Besselfunkton erster Art und $n$–ter Ordnung. $K_{\rm PM}$ ist die Modulatorkonstante.

- Durch eine andere Nachrichtenphase $ϕ_{\rm N}$ ändert sich nur die Phasenfunktion ${\rm arc} \ S_+(f)$, nicht aber das Betragsspektrum $|S_+(f)|$. Dieses wichtige Ergebnis wurde auch durch die Aufgabe 3.3Z bestätigt.

- Auf der Seite Frequenzmodulation eines Cosinussignals wurde gezeigt, dass ein FM–Signal in gleicher Weise wie ein PM–Signal dargestellt werden kann, wenn der Modulationsindex $η = K_{\rm FM} · A_{\rm N}/ω_{\rm N}$ verwendet wird. Folgerichtig sind auch die Betragsspektren bei Phasen- und Frequenzmodulation in gleicher Form darstellbar.

Wir verweisen hier gerne auch auf den zweiten Teil des Lernvideos Winkelmodulation – Frequenz– und Phasenmodulation.

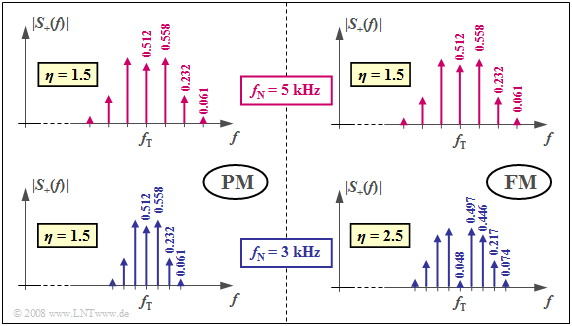

$\text{Beispiel 3:}$ Wir betrachten wieder eine harmonische Schwingung mit der Amplitude $A_{\rm N} = 3 \ \rm V$ nach

- einer Phasenmodulation mit $K_{\rm PM} = \rm 0.5 \ \rm V^{–1}$,

- einer Frequenzmodulation mit $K_{\rm FM} = \rm 15708 \ \rm V^{–1}s^{–1}$.

Die zugehörigen Signalverläufe sind im $\text{Beispiel 2}$ dargestellt.

- Bei beiden Übertragungssystemen ergibt sich für $f_{\rm N} = 5 \ \rm kHz$ ein Besselspektrum mit dem Modulationsindex $η = 1.5$.

- Die identischen Betragsspektren des analytischen Signals (nur positive Frequenzen) sind in den beiden oberen Grafiken dargestellt.

- Bessellinien mit Werten kleiner als $0.03$ sind hierbei in beiden Fällen vernachlässigt.

Die unteren Grafiken gelten für die Nachrichtenfrequenz $f_{\rm N} = 3 \ \rm kHz$:

- Bei der Phasenmodulation ergibt sich gegenüber $f_{\rm N} = 5 \ \rm kHz$ nun eine schmalere Spektralfunktion, da der Abstand der Bessellinien nur mehr $3 \ \rm kHz$ beträgt (linke untere Grafik).

- Da sich der Modulationsindex $η = 1.5$ nicht ändert, ergeben sich die gleichen Besselgewichte wie bei $f_{\rm N} = 5 \ \rm kHz$ (obere Grafik).

- Auch bei der Frequenzmodulation treten nun die Bessellinien im Abstand von $3 \ \rm kHz$ auf (rechte untere Grafik).

- Es gibt aber nun aufgrund des größeren Modulationsindex $η = 2.5$ deutlich mehr Bessellinien als im rechten oberen (für $η = 1.5$ gültigen) Diagramm.

- Dies folgt aus der Tatsache, dass bei Frequenzmodulation $η$ umgekehrt proportional zu $f_{\rm N}$ ist.

Einfluss einer Bandbegrenzung bei Winkelmodulation

Fassen wir einige bisherige Resultate dieses Abschnittss kurz zusammen, wobei wir beispielhaft die Trägerfrequenz $f_{\rm T} = 100 \ \rm kHz$, die Nachrichtenfrequenz $f_{\rm N} = 5 \ \rm kHz$ und den Modulationsindex $η = π/2 \approx 1.5$ voraussetzen:

- Das Spektrum einer winkelmodulierten Schwingung besteht aus Bessellinien um den Träger $f_{\rm T}$ im Abstand $f_{\rm N}$ der Nachrichtenfrequenz und ist theoretisch unendlich weit ausgedehnt.

- Selbst wenn man alle Spektrallinien mit Beträgen kleiner als $0.01$ vernachlässigt, beträgt die dann endliche Bandbreite für $η = π/2$ noch immer $B_{\rm HF} = 8 · f_{\rm N} = 40 \ \rm kHz$.

- Die Ortskurve – also der Verlauf des äquivalenten Tiefpass–Signals in der komplexen Ebene – ist im Idealfall ein Kreisbogen mit einem Öffnungswinkel von $±1.57 \ {\rm rad} = ±90^\circ$.

- Dieser Kreisbogen nach der vektoriellen Addition ergibt sich allerdings nur dann, wenn alle Bessellinien in der Ortskurve mit den richtigen Zeigerlängen, den richtigen Phasenlagen und den richtigen Kreisfrequenzen rotieren.

- Logischerweise wird die kreisbogenförmige Ortskurve verändert, wenn Spektrallinien verfälscht werden (zum Beispiel durch lineare Kanalverzerrungen) oder ganz fehlen (zum Beispiel durch eine Bandbegrenzung).

- Da der ideale Winkeldemodulator die Phase $ϕ_r(t)$ des Empfangssignals detektiert und daraus das Sinkensignal $v(t)$ gewinnt, wird dieses dadurch verfälscht und zwar sogar nichtlinear. Das heißt: Die Verzerrungen sind irreversibel und können nicht durch ein lineares Filter kompensiert werden.

- Das bedeutet gleichzeitig: Aufgrund linearer Verzerrungen auf dem Kanal kommt es zu nichtlinearen Verzerrungen im demodulierten Signal $v(t)$ ⇒ dadurch entstehen neue Frequenzen (Oberwellen), die im Quellensignal $q(t)$ nicht enthalten waren.

- Je kleiner die zur Verfügung stehende Bandbreite $B_{\rm HF}$ ist und je größer der Modulationsindex $η$ gewählt wird, desto größer wird der die nichtlinearen Verzerrungen beschreibende Klirrfaktor $K$. Als Faustformel für die erforderliche HF–Bandbreite für einen geforderten Klirrfaktor $K$ gilt nach der so genannten "Carson–Regel":

- $$K < 10\%\text{:}\hspace{0.6cm} B_{\rm HF} \ge 2 \cdot f_{\rm N} \cdot (\eta +1)\hspace{0.05cm},$$

- $$K < 1\%\text{:}\hspace{0.72cm} B_{\rm HF} \ge 2 \cdot f_{\rm N} \cdot(\eta +2)\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

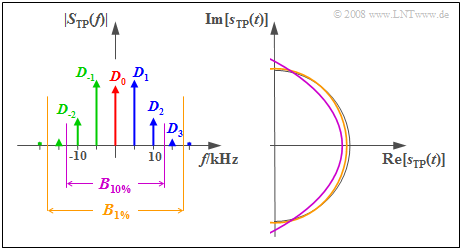

$\text{Beispiel 4:}$ Wir gehen weiterhin von den Systemparametern $f_{\rm T} = 100 \ \rm kHz$, $f_{\rm N} = 5 \ \rm kHz$ und $η = π/2$ aus. Die Grafik zeigt für diesen Fall links das Betragsspektrum $ \vert S_{\rm TP}(f) \vert$ des äquivalenten Tiefpass–Signals und rechts die zugehörige komplexe Zeitfunktion $s_{\rm TP}(t)$.

- Um den Klirrfaktor auf Werte $K < 1\%$ zu begrenzen, ist nach der Carson–Regel eine HF–Bandbreite von $B_{1 \%} ≈ 36 \ \rm kHz$ erforderlich.

- Das äquivalente Tiefpass–Signal setzt sich dann aus der Konstanten $D_0$ und je drei entgegen dem Uhrzeigersinn $(D_1, D_2, D_3)$ bzw. im Uhrzeigersinn $(D_{-1}, D_{-2}, D_{-3})$ drehenden Zeigern zusammen:

- $$\begin{align*}s_{\rm TP}(t) & = \sum_{n = - 3}^{+3}D_n \cdot{\rm e}^{\hspace{0.05cm}{\rm j} \hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm}n \hspace{0.05cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm}\omega_{\rm N} \hspace{0.02cm}\cdot \hspace{0.05cm} t }\end{align*}$$

- Die ockerfarbene Kurve in der Zeitbereichsdarstellung macht deutlich, dass sich das äquivalente Tiefpass-Signal durch diese Bandbegrenzung nur geringfügig vom verzerrungsfreien Halbkreis (dünne schwarze Linie) unterscheidet.

Gibt man sich mit einem Klirrfaktor $K < 10\%$ zufrieden, so ist bereits die HF–Bandbreite $B_{10 \%} ≈ 26\ \rm kHz$ ausreichend.

- Damit werden auch die beiden Fourierkoeffizienten $D_3$ und $D_{-3}$ abgeschnitten und die violett dargestellte Ortskurve beschreibt einen Parabelabschnitt.

- Die Simulation dieses Fallbeispiels liefert den Klirrfaktor $K ≈ 6\%$.

- Man erkennt: Die Carson–Regel liefert oft ein etwas zu pessimistisches Ergebnis $(10\%$ anstelle von $6\%)$.

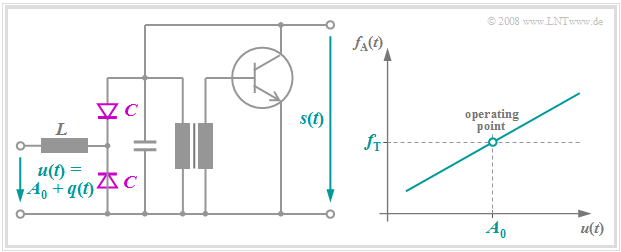

Realisierung eines FM–Modulators

Eine Frequenzmodulation erhält man dann, wenn die Schwingfrequenz eines Oszillators im Rhythmus des modulierenden Signals verändert wird. Als frequenzbestimmende Elemente dienen meist RC–Glieder oder Schwingkreise. Die linke Grafik zeigt eine schaltungstechnische Realisierungsform; die genaue Schaltungsbeschreibung finden Sie in [Mäu 88][1]. Rechts ist die idealisierte Frequenz–Spannungskennlinie dargestellt.

Hier sollen nur einige wenige Anmerkungen gemacht werden:

- Die anliegende Spannung $u(t)$ setzt sich additiv aus dem Quellensignal $q(t)$ und einem Gleichanteil $A_0$ zusammen, der den Arbeitspunkt festlegt.

- Die Kapazität $C$ der Kapazitätsdiode ist näherungsweise proportional zu $1/u^{2}(t)$, so dass sich die Schwingfrequenz des LC–Oszillators abhängig von $q(t)$ verändert.

- Bei nur kleiner Frequenzänderung hängen $u(t)$ und $f_{\rm A}(t)$ linear zusammen. Damit ist die Augenblickskreisfrequenz mit der Steigung $K_{\rm FM}$ der Modulatorkennlinie wie folgt gegeben:

- $$\omega_{\rm A}(t) = \omega_{\rm T} + K_{\rm FM} \cdot q(t) \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- Die Gegentaktschaltung aus den beiden Kapazitätsdioden dient unter Anderem zur Kompensation von Unsymmetrien und damit zur Verminderung der quadratischen Verzerrungen.

- Mit dem Eingang $A_0+{\rm d}q(t)/{\rm d}t$ erhält man am Ausgang das frequenzmodulierte Signal $s(t)$.

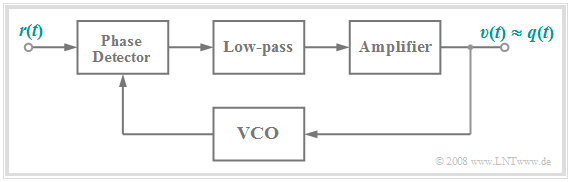

PLL–Realisierung eines FM–Demodulators

Die folgende Grafik zeigt eine zweite Realisierungsmöglichkeit des FM–Demodulators. Eine detaillierte Schaltungsbeschreibung dieses PLL–FM–Demodulators und weitere FM–Demodulatoren – zum Beispiel mittels Flankendiskriminator – finden Sie in [Mäu 88][1].

In Stichpunkten lässt sich diese Schaltung, die als Phasenregelschleife $($Phase–Locked–Loop, $\rm PLL)$ arbeitet, wie folgt beschreiben:

- Der Phasendetektor ermittelt die Phasenunterschiede (Abstände der Nulldurchgänge) zwischen dem Empfangssignal $r(t)$ und dem vom VCO bereitgestellten Vergleichssignal.

- Das Ausgangssignal $v(t)$ nach Tiefpass–Filterung und Verstärkung ist dann näherungsweise gleich dem Quellensignal $q(t)$, wenn dieses sendeseitig FM–moduliert wurde.

- Das Ausgangssignal $v(t)$ wird gleichzeitig an den Eingang des spannungsgesteuerten Oszillators angelegt. Man bezeichnet diesen auch als Voltage Controlled Oscillator, abgekürzt $\rm VCO$.

- Das Ausgangssignal des VCO wird permanent in der Weise nachgeregelt, dass dessen Frequenz möglichst der Augenblicksfrequenz $f_{\rm A}(t)$ des Empfangssignals $r(t)$ entspricht.

Aufgaben zum Kapitel

Aufgabe 3.5: PM und FM bei Rechtecksignalen

Aufgabe 3.5Z: Phasenmodulation eines Trapezsignals

Aufgabe 3.6: PM oder FM? Oder AM?

Aufgabe 3.7: Winkelmodulation einer harmonischen Schwingung

Aufgabe 3.8: Modulationsindex und Bandbreite

Aufgabe 3.9: Kreisbogen und Parabel

Quellenverzeichnis