Difference between revisions of "Modulation Methods/Quality Criteria"

| (109 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Header | {{Header | ||

| − | |Untermenü= | + | |Untermenü=General Description |

| − | |Vorherige Seite= | + | |Vorherige Seite=Objectives of Modulation and Demodulation |

| − | |Nächste Seite= | + | |Nächste Seite=General Model of Modulation |

}} | }} | ||

| − | == | + | ==Ideal and distortionless system== |

| − | In | + | <br> |

| + | [[File:EN_Mod_T_1_2_S1.png |right|frame| Block diagram describing modulation and demodulation]] | ||

| + | In all subsequent chapters, the following model will be assumed: | ||

| + | The task of any message transmission system is | ||

| + | *to provide a sink signal $v(t)$ at a spatially distant sink | ||

| + | |||

| + | *that differs as little as possible from the source signal $q(t)$ . | ||

| + | <br clear=all> | ||

| + | {{BlaueBox|TEXT= | ||

| + | $\text{Definition:}$ An »'''ideal system'''« is achieved when the following conditions hold: | ||

| + | :$$v(t) = q(t) + n(t), \hspace{1cm}n(t) \to 0.$$ | ||

| + | This takes into account that $n(t) \equiv 0$ is physically impossible due to [[Aufgaben:Exercise_1.3Z:_Thermal_Noise|$\text{thermal noise}$]].}} | ||

| − | |||

| + | In practice, the signals $q(t)$ and $v(t)$ will not differ by more than the noise term $n(t)$ for the following reasons: | ||

| − | + | *Non-ideal realization of the modulator and the demodulator, | |

| − | + | *linear attenuation distortions and phase distortions, as well as nonlinearities, | |

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | *external disturbances and additional stochastic noise processes, | ||

| − | + | *frequency-independent attenuation and delay. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | {{BlaueBox|TEXT= | |

| − | + | $\text{Definition:}$ A »'''distortionless system'''« is achieved, if from the above list only the last restriction is effective: | |

| − | $$ | + | :$$v(t) = \alpha \cdot q(t- \tau) + n(t), \hspace{1cm}n(t) \to 0.$$}} |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | *Due to the attenuation factor $α$, the sink signal $v(t)$ is only "quieter" compared to the source signal $q(t)$. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Even a delay $τ$ is often tolerable, at least for a unidirectional transmission. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *In contrast, in bidirectional communications – such as a telephone call – a delay of $300$ milliseconds is already perceived as a significant disturbance. | ||

| − | + | ==Signal–to–noise (power) ratio== | |

| − | $$ | + | <br> |

| − | + | In the general case, the sink signal $v(t)$ will still differ from $α · q(t - τ)$, and the error signal is characterized by: | |

| − | + | :$$\varepsilon (t) = v(t) - \alpha \cdot q(t- \tau) = \varepsilon_{\rm V} (t) + \varepsilon_{\rm St} (t).$$ | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | This error signal is composed of two components: | |

| − | $ | + | *linear and nonlinear distortions (German: "Verzerrungen" ⇒ subscript "V") $ε_{\rm V}(t)$, which are caused by the frequency responses of the modulator, the channel, and the demodulator and thus exhibit deterministic (time-invariant) behavior; |

| − | + | *a stochastic component $ε_{\rm St}(t)$, which originates from the high-frequency noise $n(t)$ at the demodulator input. However, unlike $n(t)$, $ε_{\rm St}(t)$ is usually due to a low-frequency noise disturbance in a demodulator with a low-pass characteristic curve. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | $$ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | {{BlaueBox|TEXT= | ||

| + | $\text{Definition:}$ As a measure of the quality of the communication system, the »'''signal-to-noise (power) ratio'''« $\rm (SNR)$ $ρ_v$ at the sink is defined as the quotient of the signal power (variance) of the useful component $v(t) - ε(t)$ and the disturbing component $ε(t)$, respectively: | ||

| + | :$$\rho_{v} = \frac{ P_{v -\varepsilon} }{P_{\varepsilon} } \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.7cm}\text{with}\hspace{0.7cm} P_{v -\varepsilon} = \overline{[v(t)-\varepsilon(t)]^2} = \lim_{T_{\rm M} \rightarrow \infty}\hspace{0.1cm}\frac{1}{T_{\rm M} } \cdot \int_{0}^{ T_{\rm M} } | ||

| + | {\big[v(t)-\varepsilon(t)\big]^2 }\hspace{0.1cm}{\rm d}t,\hspace{0.5cm} | ||

| + | P_{\varepsilon} = \overline{\varepsilon^2(t)} = \lim_{T_{\rm M} \rightarrow \infty}\hspace{0.1cm}\frac{1}{T_{\rm M} } \cdot \int_{0}^{ T_{\rm M} } | ||

| + | {\varepsilon^2(t) }\hspace{0.1cm}{\rm d}t\hspace{0.05cm}.$$}} | ||

| − | |||

| + | For the power of the useful part, we obtain regardless of the delay time $τ$: | ||

| + | :$$P_{v -\varepsilon} = \overline{\big[v(t)-\varepsilon(t)\big]^2} = \overline{\alpha^2 \cdot q^2(t - \tau)}= \alpha^2 \cdot P_{q}.$$ | ||

| + | Here, $P_q$ denotes the power of the source signal $q(t)$: | ||

| + | :$$P_{q} = \lim_{T_{\rm M} \rightarrow \infty}\hspace{0.1cm}\frac{1}{T_{\rm M}} \cdot \int_{0}^{ T_{\rm M}} {q^2(t) }\hspace{0.1cm}{\rm d}t .$$ | ||

| − | + | {{BlaueBox|TEXT= This gives: | |

| + | :$$\rho_{v} = \frac{\alpha^2 \cdot P_{q} }{P_{\varepsilon} } \hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} 10 \cdot {\rm lg}\hspace{0.15cm}\rho_{v} = | ||

| + | 10 \cdot {\rm lg} \hspace{0.15cm} \frac{\alpha^2 \cdot P_{q} }{P_{\varepsilon} } \hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| + | *In the following, we will refer to $ρ_v$ as the »'''sink signal–to–noise ratio'''« or short: »'''sink SNR'''«. | ||

| + | *One often uses the logarithmic form ⇒ $10 · \lg \ ρ_v$ which is expressed in $\rm dB$ when using the logarithm of base ten $(\lg)$ .}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[File:P_ID941__Mod_T_1_2_S2_neu.png |right|frame|Illustrating the remaining error signal $ε(t) = v(t) - α · q(t - τ)$]] | |

| − | + | {{GraueBox|TEXT= | |

| − | + | $\text{Example 1:}$ On the right, you can see an exemplary section of the (blue) source signal $q(t)$ and the (red) sink signal $v(t)$, which are noticeably different. | |

| − | |||

| + | However, the middle graph makes it clear that the main difference between $q(t)$ and $v(t)$ is due to the attenuation factor $α = 0.7$ and the transmission delay $τ = 0.1\text{ ms}$. | ||

| − | + | The bottom sketch shows the remaining error signal $ε(t) = v(t) - α · q(t - τ)$ after correcting for attenuation and delay. We refer to the mean square ⇒ "variance" of this signal as the noise power $P_ε$. | |

| − | + | To calculate the sink SNR $ρ_v$ , $P_ε$ must be related to the useful signal power $α^2 · P_q$. This is obtained from the variance of the signal $α · q(t - τ)$, plotted in light blue in the middle graph. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | From the assumed properties $\alpha = 0.7$ ⇒ $\alpha^2 \approx 0.5$ as well as $P_{q} = 8\,{\rm V^2}$ and ${P_{\varepsilon} } = 0.04\,{\rm V^2}$ , we obtain the sink SNR | ||

| + | :$$ ρ_v ≈ 100 \hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}10 · \lg ρ_v ≈ 20\ \rm dB.$$ | ||

| − | + | *The error signal $ε(t)$ – and thus also the sink SNR $ρ_v$ – takes into account all imperfections of the transmission system under consideration (e.g. distortions, external interferences, noise, etc.). | |

| − | * | + | *In the following, we will consider each of these different effects separately for the sake of explanation.}} |

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | ==Investigations with regard to signal distortions== | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | All modulation methods described in the following chapters lead to distortions under non-ideal conditions, i.e. to a sink signal | ||

| + | [[File:EN_Mod_T_1_2_S3.png|right|frame| Simplified model of a communication system]] | ||

| + | :$$v(t) ≠ α · q(t - τ),$$ | ||

| + | which differs from $q(t)$ by more than just attenuation and delay. For the study of these signal distortions, we always assume the following model and premises: | ||

| − | + | *The additive noise signal $n(t)$ at the channel output (demodulator input) is negligible and ignored. | |

| + | *All components of modulator and demodulator are treated as linear. | ||

| + | *Similarly, the channel is assumed to be linear, and is thus completely characterized by its frequency response $H_{\rm K}(f)$ . | ||

| + | <br clear=all> | ||

| + | Depending on the type and realization of modulator and demodulator, the following signal distortions occur: | ||

| + | {{BlaueBox|TEXT= | ||

| + | $\text{Linear distortions}$, as described in the [[Linear_and_Time_Invariant_Systems/Linear_Distortions|"chapter of the same name"]] in the book "Linear and Time-Invariant Systems": | ||

| + | *Linear distortions can generally be compensated by an equalizer, but this will always result in higher $P_\epsilon$ and thus in a lower sink SNR in the presence of a stochastic disturbance $n(t)$. | ||

| + | *These linear distortions can be further divided into "attenuation distortions" and "phase distortions". | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | $\text{Nonlinear distortions}$, as described in the [[Linear_and_Time_Invariant_Systems/Nonlinear_Distortions|"chapter of the same name"]] in the book "Linear and Time-Invariant Systems": | |

| + | *Nonlinear distortions are irreversible and thus a more severe problem than linear distortions. | ||

| + | *A suitable quantitative measure of such distortions is the distortion factor $K$, for example, which is related to the sink SNR in the following way: $\rho_{v} = {1}/{K^2} \hspace{0.05cm}.$ | ||

| + | *However, specifying a distortion factor assumes a harmonic oscillation as the source signal.}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | Lineare und nichtlineare Verzerrungen | + | We refer you to three of our (German language) basic learning videos: |

| + | *[[Lineare_und_nichtlineare_Verzerrungen_(Lernvideo)|"Lineare und nichtlineare Verzerrungen"]] ⇒ "Linear and nonlinear distortions", | ||

| + | *[[Eigenschaften_des_Übertragungskanals_(Lernvideo)|"Eigenschaften des Übertragungskanals"]] ⇒ "Properties of the transmission channel", | ||

| + | *[[Einige_Anmerkungen_zur_Übertragungsfunktion_(Lernvideo)|"Einige Anmerkungen zur Übertragungsfunktion"]] ⇒ "Some remarks on the transmission function". | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | {{BlaueBox|TEXT= | ||

| + | $\text{Two further points:}$ | ||

| + | # The distortions with respect to $q(t)$ and $v(t)$ are nonlinear in nature whenever the channel contains nonlinear components and, as such, <br>nonlinear distortions are already present with respect to the signals $s(t)$ and $r(t)$. | ||

| + | # Similarly, nonlinearities in the modulator or demodulator always lead to nonlinear distortions.}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | ==Some remarks on the AWGN channel model== | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | To investigate the noise behavior of each individual modulation and demodulation method, the starting point is usually the so-called $\rm AWGN$ channel, where the abbreviation stands for "$\rm A$dditive $\rm W$hite $\rm G$aussian $\rm N$oise". The name already sufficiently describes the properties of this channel model. | ||

| − | + | We would also like to refer you to the (German language) three-part learning video [[Der_AWGN-Kanal_(Lernvideo)|"Der AWGN-Kanal"]] ⇒ "The AWGN channel". | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | ( | ||

| − | + | *The additive noise signal includes all frequency components equally ⇒ $n(t)$ has a constant power-spectral density $\rm (PSD)$ and a Dirac-shaped auto-correlation function $\rm (ACF)$: | |

| − | * | + | :$${\it \Phi}_n(f) = \frac{N_0}{2}\hspace{0.15cm} \bullet\!\!-\!\!\!-\!\!\!-\!\!\circ\, |

| − | $$N = \sigma_n^2 = {N_0} \cdot B \hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | + | \hspace{0.15cm} \varphi_n(\tau) = \frac{N_0}{2} \cdot \delta (\tau)\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ |

| − | + | :In each case, the factor $1/2$ in these equations accounts for the two-sided spectral representation. | |

| − | + | *For example, in the case of thermal noise, for the physical noise power density (from a one-sided view) with a noise figure $F ≥ 1$ and an absolute temperature $θ$: | |

| − | * | + | :$${N_0}= F \cdot k_{\rm B} \cdot \theta , \hspace{0.5cm}\text{Boltzmann constant:}\hspace{0.3cm}k_{\rm B} = |

| − | $$f_n(n) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}\cdot\sigma_n}\cdot {\rm e}^{-{\it | + | 1.38 \cdot 10^{-23}{ {\rm Ws} }/{ {\rm K} }\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ |

| + | *"True white noise" would result in infinitely large power. Therefore, a bandwidth limit of $B$ must always be taken into account, and the following applies to the effective noise power: | ||

| + | :$$N = \sigma_n^2 = {N_0} \cdot B \hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| + | *The noise signal $n(t)$ has a Gaussian probability density function $\rm (PDF)$ ⇒ a normal amplitude distribution with standard deviation $σ_n$: | ||

| + | :$$f_n(n) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}\cdot\sigma_n}\cdot {\rm e}^{-{\it | ||

n^{\rm 2}}/{(2\sigma_{\it n}^2)}}.$$ | n^{\rm 2}}/{(2\sigma_{\it n}^2)}}.$$ | ||

| + | *For the AWGN channel, one should actually set $H_{\rm K}(f) = 1$. However, we modify this model for our purposes by allowing frequency-independent attenuation <br>(note: a frequency-independent attenuation factor does not lead to further distortions): | ||

| + | :$$H_{\rm K}(f) = \alpha_{\rm K}= {\rm const.}$$ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | ==Investigations at the AWGN channel == | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | In all investigations regarding noise behavior, we start from the block diagram sketched below. We will always calculate the sink SNR $ρ_v$ as a function of all system parameters and arrive at the following results: | ||

| + | [[File: EN_Mod_T_1_2_S5.png |right|frame| Block diagram for investigating noise behavior]] | ||

| − | + | *The more transmit power (German: "Sendeleistung" ⇒ subscript "S") $P_{\rm S}$ we apply, the greater is the sink SNR $ρ_v$. For some methods, this relationship can even be linear. | |

| + | *$ρ_v$ decreases monotonically with increasing noise power density $N_0$ . An increase in $N_0$ can usually be compensated by a larger transmit power $P_{\rm S}$. | ||

| + | *The smaller the channel's $α_{\rm K}$ parameter, the smaller $ρ_v$ becomes. There is often a quadratic relationship, since the received power (German: "Empfangsleistung" ⇒ subscript "E") is $P_{\rm E} = {α_{\rm K}}^2 · P_{\rm S}$. | ||

| + | *A wider bandwidth of the source signal $($larger $B_{\rm NF})$ requires an increased high-frequency bandwidth $B_{\rm HF}$, too ⇒ this leads to smaller sink SNR $ρ_v$ ⇒ negative effect on the transmission system's quality. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | {{BlaueBox|TEXT= | |

| + | $\text{Conclusion:}$ Considering these four assumptions, we conclude that it makes sense to express the sink SNR in normalized form as | ||

| + | :$$\rho_{v } = \rho_{v }(\xi) \hspace{0.5cm} {\rm with} \hspace{0.5cm}\xi = \frac{ {\alpha_{\rm K} }^2 \cdot P_{\rm S} }{N_0 \cdot B_{\rm NF} }.$$ | ||

| + | In the following, we refer to $ξ$ as the »'''performance parameter'''«.}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | The input variables summarized in $ξ$ are marked with blue arrows in the above block diagram, while the quality criterion $ρ_v$ is highlighted by the red arrow. | ||

| + | * The larger $ξ$ is, the larger is $\rho_{v }$ in general. | ||

| + | * But the relationship is not always linear, as the following example shows. | ||

| − | |||

| + | [[File:P_ID947__Mod_T_1_2_S5b_neu.png |right|frame| The AWGN Channel]] | ||

| + | {{GraueBox|TEXT= | ||

| + | $\text{Example 2:}$ The left graph shows the sink SNR $ρ_v$ of three different systems, each as a function of the normalized performance parameter | ||

| + | :$$\xi = { {\alpha_{\rm K} }^2 \cdot P_{\rm S} }/({N_0 \cdot B_{\rm NF} }).$$ | ||

| − | + | *For $\text{System A}$, $ρ_ν = ξ$ holds. The system parameters | |

| − | * | + | :$$P_{\rm S}= 10 \;{\rm kW}\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} |

| − | + | \alpha_{\rm K} = 10^{-4}\hspace{0.05cm},$$ | |

| − | + | :$$ {N_0} = | |

| − | + | 10^{-12}\hspace{0.05cm}{ {\rm W} }/{ {\rm Hz} }\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} | |

| + | B_{\rm NF}= 10\; {\rm kHz}$$ | ||

| + | :give $ξ = ρ_v = 10000$ (see the circular mark on the graph). | ||

| + | *Exactly the same sink SNR would result from the parameters | ||

| + | :$$P_{\rm S}= 5 \;{\rm kW}\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} | ||

| + | \alpha_{\rm K} = 10^{-6}\hspace{0.05cm},$$ | ||

| + | :$${N_0} = | ||

| + | 10^{-16}\hspace{0.05cm}{ {\rm W} }/{ {\rm Hz} }\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} | ||

| + | B_{\rm NF}= 5\; {\rm kHz}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$ | ||

| + | *In $\text{System B}$, there is also a linear relationship of $ρ_v = ξ/3$. The line also passes through the origin. However, the slope is only $1/3$. | ||

| + | *It should be noted that the noise behavior corresponding to $\text{System A}$ is observed for [[Modulation_Methods/Double-Sideband_Amplitude_Modulation#Description_in_the_frequency_domain|$\text{double-sideband suppressed-carrier amplitude modulation}$]] $($modulation depth $m → ∞)$, while $\text{System B}$ describes [[Modulation_Methods/Double-Sideband_Amplitude_Modulation#Double-Sideband_Amplitude_Modulation_with_carrier|$\text{double-sideband amplitude modulation with carrier}$]] $(m ≈ 0.5)$. | ||

| + | *$\text{System C}$ shows a completely different noise behavior. For small $ξ$–values, this system is superior to $\text{System A}$, though the quality of both systems is the same at $ξ = 10000$. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Increasing the performance parameter $ξ$ does not significantly improve $\text{System C}$, unlike in $\text{System A}$. Such behavior can be observed, for example, in digital systems where the sink SNR is limited by the quantization noise. Along the horizontal section of the curve, a higher transmit power will not result in a better sink SNR – and thus a smaller bit error probability. | |

| − | + | Usually, the quantities $ρ_v$ and $ξ$ are represented in logarithmic form, as shown in the graph on the right: | |

| − | + | *The double logarithmic representation still results in the angle bisector for $\text{System A}$ . | |

| − | + | *The lower slope $($factor $3)$ of $\text{System B}$ now results in a downward shift of $10 · \lg 3 ≈ 5\text{ dB}$. | |

| − | + | *The intersection of $\text{A}$ and $\text{C}$ shifts from $ξ = ρ_v = 10000$ to $10 · \lg ξ = 10 · \lg ρ_v = 40\text{ dB}$ due to the double-logarithmic representation. }} | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | $$ | ||

| − | \ | ||

| − | 10 | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | ==Exercises for the chapter== | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | [[Aufgaben:Exercise_1.2:_Distortions%3F_Or_no_Distortion%3F|Exercise 1.2: Distortion? Or no distortion?]] | ||

| − | + | [[Aufgaben:Exercise_1.2Z:_Linear_Distorting_System|Exercise 1.2Z: Linear distorting system]] | |

| − | + | [[Aufgaben:Exercise_1.3:_System_Comparison_at_AWGN_Channel|Exercise 1.3: System comparison at the AWGN channel]] | |

| − | + | [[Aufgaben:Exercise_1.3Z:_Thermal_Noise|Exercise 1.3Z: Thermal noise]] | |

| − | |||

{{Display}} | {{Display}} | ||

Latest revision as of 19:01, 12 January 2023

Contents

Ideal and distortionless system

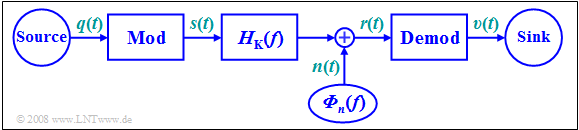

In all subsequent chapters, the following model will be assumed:

The task of any message transmission system is

- to provide a sink signal $v(t)$ at a spatially distant sink

- that differs as little as possible from the source signal $q(t)$ .

$\text{Definition:}$ An »ideal system« is achieved when the following conditions hold:

- $$v(t) = q(t) + n(t), \hspace{1cm}n(t) \to 0.$$

This takes into account that $n(t) \equiv 0$ is physically impossible due to $\text{thermal noise}$.

In practice, the signals $q(t)$ and $v(t)$ will not differ by more than the noise term $n(t)$ for the following reasons:

- Non-ideal realization of the modulator and the demodulator,

- linear attenuation distortions and phase distortions, as well as nonlinearities,

- external disturbances and additional stochastic noise processes,

- frequency-independent attenuation and delay.

$\text{Definition:}$ A »distortionless system« is achieved, if from the above list only the last restriction is effective:

- $$v(t) = \alpha \cdot q(t- \tau) + n(t), \hspace{1cm}n(t) \to 0.$$

- Due to the attenuation factor $α$, the sink signal $v(t)$ is only "quieter" compared to the source signal $q(t)$.

- Even a delay $τ$ is often tolerable, at least for a unidirectional transmission.

- In contrast, in bidirectional communications – such as a telephone call – a delay of $300$ milliseconds is already perceived as a significant disturbance.

Signal–to–noise (power) ratio

In the general case, the sink signal $v(t)$ will still differ from $α · q(t - τ)$, and the error signal is characterized by:

- $$\varepsilon (t) = v(t) - \alpha \cdot q(t- \tau) = \varepsilon_{\rm V} (t) + \varepsilon_{\rm St} (t).$$

This error signal is composed of two components:

- linear and nonlinear distortions (German: "Verzerrungen" ⇒ subscript "V") $ε_{\rm V}(t)$, which are caused by the frequency responses of the modulator, the channel, and the demodulator and thus exhibit deterministic (time-invariant) behavior;

- a stochastic component $ε_{\rm St}(t)$, which originates from the high-frequency noise $n(t)$ at the demodulator input. However, unlike $n(t)$, $ε_{\rm St}(t)$ is usually due to a low-frequency noise disturbance in a demodulator with a low-pass characteristic curve.

$\text{Definition:}$ As a measure of the quality of the communication system, the »signal-to-noise (power) ratio« $\rm (SNR)$ $ρ_v$ at the sink is defined as the quotient of the signal power (variance) of the useful component $v(t) - ε(t)$ and the disturbing component $ε(t)$, respectively:

- $$\rho_{v} = \frac{ P_{v -\varepsilon} }{P_{\varepsilon} } \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.7cm}\text{with}\hspace{0.7cm} P_{v -\varepsilon} = \overline{[v(t)-\varepsilon(t)]^2} = \lim_{T_{\rm M} \rightarrow \infty}\hspace{0.1cm}\frac{1}{T_{\rm M} } \cdot \int_{0}^{ T_{\rm M} } {\big[v(t)-\varepsilon(t)\big]^2 }\hspace{0.1cm}{\rm d}t,\hspace{0.5cm} P_{\varepsilon} = \overline{\varepsilon^2(t)} = \lim_{T_{\rm M} \rightarrow \infty}\hspace{0.1cm}\frac{1}{T_{\rm M} } \cdot \int_{0}^{ T_{\rm M} } {\varepsilon^2(t) }\hspace{0.1cm}{\rm d}t\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

For the power of the useful part, we obtain regardless of the delay time $τ$:

- $$P_{v -\varepsilon} = \overline{\big[v(t)-\varepsilon(t)\big]^2} = \overline{\alpha^2 \cdot q^2(t - \tau)}= \alpha^2 \cdot P_{q}.$$

Here, $P_q$ denotes the power of the source signal $q(t)$:

- $$P_{q} = \lim_{T_{\rm M} \rightarrow \infty}\hspace{0.1cm}\frac{1}{T_{\rm M}} \cdot \int_{0}^{ T_{\rm M}} {q^2(t) }\hspace{0.1cm}{\rm d}t .$$

This gives:

- $$\rho_{v} = \frac{\alpha^2 \cdot P_{q} }{P_{\varepsilon} } \hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} 10 \cdot {\rm lg}\hspace{0.15cm}\rho_{v} = 10 \cdot {\rm lg} \hspace{0.15cm} \frac{\alpha^2 \cdot P_{q} }{P_{\varepsilon} } \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- In the following, we will refer to $ρ_v$ as the »sink signal–to–noise ratio« or short: »sink SNR«.

- One often uses the logarithmic form ⇒ $10 · \lg \ ρ_v$ which is expressed in $\rm dB$ when using the logarithm of base ten $(\lg)$ .

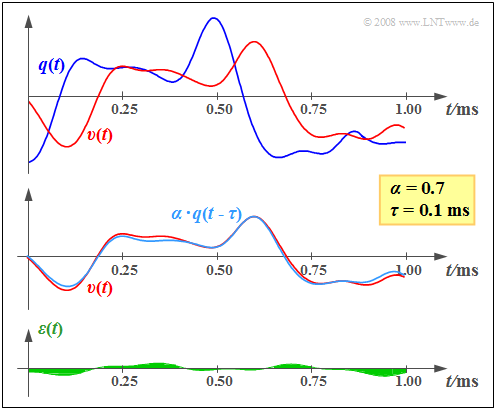

$\text{Example 1:}$ On the right, you can see an exemplary section of the (blue) source signal $q(t)$ and the (red) sink signal $v(t)$, which are noticeably different.

However, the middle graph makes it clear that the main difference between $q(t)$ and $v(t)$ is due to the attenuation factor $α = 0.7$ and the transmission delay $τ = 0.1\text{ ms}$.

The bottom sketch shows the remaining error signal $ε(t) = v(t) - α · q(t - τ)$ after correcting for attenuation and delay. We refer to the mean square ⇒ "variance" of this signal as the noise power $P_ε$.

To calculate the sink SNR $ρ_v$ , $P_ε$ must be related to the useful signal power $α^2 · P_q$. This is obtained from the variance of the signal $α · q(t - τ)$, plotted in light blue in the middle graph.

From the assumed properties $\alpha = 0.7$ ⇒ $\alpha^2 \approx 0.5$ as well as $P_{q} = 8\,{\rm V^2}$ and ${P_{\varepsilon} } = 0.04\,{\rm V^2}$ , we obtain the sink SNR

- $$ ρ_v ≈ 100 \hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}10 · \lg ρ_v ≈ 20\ \rm dB.$$

- The error signal $ε(t)$ – and thus also the sink SNR $ρ_v$ – takes into account all imperfections of the transmission system under consideration (e.g. distortions, external interferences, noise, etc.).

- In the following, we will consider each of these different effects separately for the sake of explanation.

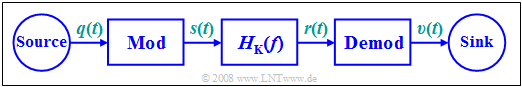

Investigations with regard to signal distortions

All modulation methods described in the following chapters lead to distortions under non-ideal conditions, i.e. to a sink signal

- $$v(t) ≠ α · q(t - τ),$$

which differs from $q(t)$ by more than just attenuation and delay. For the study of these signal distortions, we always assume the following model and premises:

- The additive noise signal $n(t)$ at the channel output (demodulator input) is negligible and ignored.

- All components of modulator and demodulator are treated as linear.

- Similarly, the channel is assumed to be linear, and is thus completely characterized by its frequency response $H_{\rm K}(f)$ .

Depending on the type and realization of modulator and demodulator, the following signal distortions occur:

$\text{Linear distortions}$, as described in the "chapter of the same name" in the book "Linear and Time-Invariant Systems":

- Linear distortions can generally be compensated by an equalizer, but this will always result in higher $P_\epsilon$ and thus in a lower sink SNR in the presence of a stochastic disturbance $n(t)$.

- These linear distortions can be further divided into "attenuation distortions" and "phase distortions".

$\text{Nonlinear distortions}$, as described in the "chapter of the same name" in the book "Linear and Time-Invariant Systems":

- Nonlinear distortions are irreversible and thus a more severe problem than linear distortions.

- A suitable quantitative measure of such distortions is the distortion factor $K$, for example, which is related to the sink SNR in the following way: $\rho_{v} = {1}/{K^2} \hspace{0.05cm}.$

- However, specifying a distortion factor assumes a harmonic oscillation as the source signal.

We refer you to three of our (German language) basic learning videos:

- "Lineare und nichtlineare Verzerrungen" ⇒ "Linear and nonlinear distortions",

- "Eigenschaften des Übertragungskanals" ⇒ "Properties of the transmission channel",

- "Einige Anmerkungen zur Übertragungsfunktion" ⇒ "Some remarks on the transmission function".

$\text{Two further points:}$

- The distortions with respect to $q(t)$ and $v(t)$ are nonlinear in nature whenever the channel contains nonlinear components and, as such,

nonlinear distortions are already present with respect to the signals $s(t)$ and $r(t)$. - Similarly, nonlinearities in the modulator or demodulator always lead to nonlinear distortions.

Some remarks on the AWGN channel model

To investigate the noise behavior of each individual modulation and demodulation method, the starting point is usually the so-called $\rm AWGN$ channel, where the abbreviation stands for "$\rm A$dditive $\rm W$hite $\rm G$aussian $\rm N$oise". The name already sufficiently describes the properties of this channel model.

We would also like to refer you to the (German language) three-part learning video "Der AWGN-Kanal" ⇒ "The AWGN channel".

- The additive noise signal includes all frequency components equally ⇒ $n(t)$ has a constant power-spectral density $\rm (PSD)$ and a Dirac-shaped auto-correlation function $\rm (ACF)$:

- $${\it \Phi}_n(f) = \frac{N_0}{2}\hspace{0.15cm} \bullet\!\!-\!\!\!-\!\!\!-\!\!\circ\, \hspace{0.15cm} \varphi_n(\tau) = \frac{N_0}{2} \cdot \delta (\tau)\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- In each case, the factor $1/2$ in these equations accounts for the two-sided spectral representation.

- For example, in the case of thermal noise, for the physical noise power density (from a one-sided view) with a noise figure $F ≥ 1$ and an absolute temperature $θ$:

- $${N_0}= F \cdot k_{\rm B} \cdot \theta , \hspace{0.5cm}\text{Boltzmann constant:}\hspace{0.3cm}k_{\rm B} = 1.38 \cdot 10^{-23}{ {\rm Ws} }/{ {\rm K} }\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- "True white noise" would result in infinitely large power. Therefore, a bandwidth limit of $B$ must always be taken into account, and the following applies to the effective noise power:

- $$N = \sigma_n^2 = {N_0} \cdot B \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- The noise signal $n(t)$ has a Gaussian probability density function $\rm (PDF)$ ⇒ a normal amplitude distribution with standard deviation $σ_n$:

- $$f_n(n) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}\cdot\sigma_n}\cdot {\rm e}^{-{\it n^{\rm 2}}/{(2\sigma_{\it n}^2)}}.$$

- For the AWGN channel, one should actually set $H_{\rm K}(f) = 1$. However, we modify this model for our purposes by allowing frequency-independent attenuation

(note: a frequency-independent attenuation factor does not lead to further distortions):

- $$H_{\rm K}(f) = \alpha_{\rm K}= {\rm const.}$$

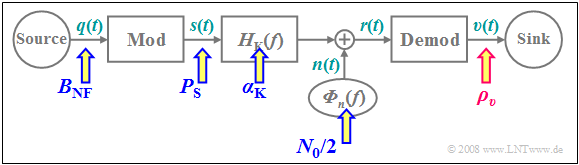

Investigations at the AWGN channel

In all investigations regarding noise behavior, we start from the block diagram sketched below. We will always calculate the sink SNR $ρ_v$ as a function of all system parameters and arrive at the following results:

- The more transmit power (German: "Sendeleistung" ⇒ subscript "S") $P_{\rm S}$ we apply, the greater is the sink SNR $ρ_v$. For some methods, this relationship can even be linear.

- $ρ_v$ decreases monotonically with increasing noise power density $N_0$ . An increase in $N_0$ can usually be compensated by a larger transmit power $P_{\rm S}$.

- The smaller the channel's $α_{\rm K}$ parameter, the smaller $ρ_v$ becomes. There is often a quadratic relationship, since the received power (German: "Empfangsleistung" ⇒ subscript "E") is $P_{\rm E} = {α_{\rm K}}^2 · P_{\rm S}$.

- A wider bandwidth of the source signal $($larger $B_{\rm NF})$ requires an increased high-frequency bandwidth $B_{\rm HF}$, too ⇒ this leads to smaller sink SNR $ρ_v$ ⇒ negative effect on the transmission system's quality.

$\text{Conclusion:}$ Considering these four assumptions, we conclude that it makes sense to express the sink SNR in normalized form as

- $$\rho_{v } = \rho_{v }(\xi) \hspace{0.5cm} {\rm with} \hspace{0.5cm}\xi = \frac{ {\alpha_{\rm K} }^2 \cdot P_{\rm S} }{N_0 \cdot B_{\rm NF} }.$$

In the following, we refer to $ξ$ as the »performance parameter«.

The input variables summarized in $ξ$ are marked with blue arrows in the above block diagram, while the quality criterion $ρ_v$ is highlighted by the red arrow.

- The larger $ξ$ is, the larger is $\rho_{v }$ in general.

- But the relationship is not always linear, as the following example shows.

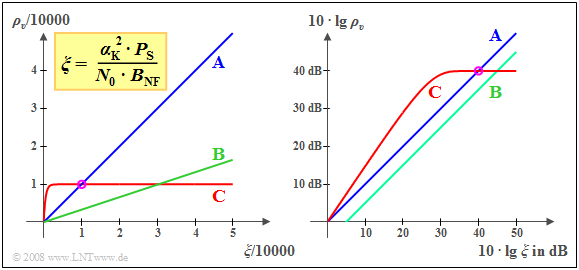

$\text{Example 2:}$ The left graph shows the sink SNR $ρ_v$ of three different systems, each as a function of the normalized performance parameter

- $$\xi = { {\alpha_{\rm K} }^2 \cdot P_{\rm S} }/({N_0 \cdot B_{\rm NF} }).$$

- For $\text{System A}$, $ρ_ν = ξ$ holds. The system parameters

- $$P_{\rm S}= 10 \;{\rm kW}\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} \alpha_{\rm K} = 10^{-4}\hspace{0.05cm},$$

- $$ {N_0} = 10^{-12}\hspace{0.05cm}{ {\rm W} }/{ {\rm Hz} }\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} B_{\rm NF}= 10\; {\rm kHz}$$

- give $ξ = ρ_v = 10000$ (see the circular mark on the graph).

- Exactly the same sink SNR would result from the parameters

- $$P_{\rm S}= 5 \;{\rm kW}\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} \alpha_{\rm K} = 10^{-6}\hspace{0.05cm},$$

- $${N_0} = 10^{-16}\hspace{0.05cm}{ {\rm W} }/{ {\rm Hz} }\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm} B_{\rm NF}= 5\; {\rm kHz}\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- In $\text{System B}$, there is also a linear relationship of $ρ_v = ξ/3$. The line also passes through the origin. However, the slope is only $1/3$.

- It should be noted that the noise behavior corresponding to $\text{System A}$ is observed for $\text{double-sideband suppressed-carrier amplitude modulation}$ $($modulation depth $m → ∞)$, while $\text{System B}$ describes $\text{double-sideband amplitude modulation with carrier}$ $(m ≈ 0.5)$.

- $\text{System C}$ shows a completely different noise behavior. For small $ξ$–values, this system is superior to $\text{System A}$, though the quality of both systems is the same at $ξ = 10000$.

Increasing the performance parameter $ξ$ does not significantly improve $\text{System C}$, unlike in $\text{System A}$. Such behavior can be observed, for example, in digital systems where the sink SNR is limited by the quantization noise. Along the horizontal section of the curve, a higher transmit power will not result in a better sink SNR – and thus a smaller bit error probability.

Usually, the quantities $ρ_v$ and $ξ$ are represented in logarithmic form, as shown in the graph on the right:

- The double logarithmic representation still results in the angle bisector for $\text{System A}$ .

- The lower slope $($factor $3)$ of $\text{System B}$ now results in a downward shift of $10 · \lg 3 ≈ 5\text{ dB}$.

- The intersection of $\text{A}$ and $\text{C}$ shifts from $ξ = ρ_v = 10000$ to $10 · \lg ξ = 10 · \lg ρ_v = 40\text{ dB}$ due to the double-logarithmic representation.

Exercises for the chapter

Exercise 1.2: Distortion? Or no distortion?

Exercise 1.2Z: Linear distorting system

Exercise 1.3: System comparison at the AWGN channel