Contents

- 1 General description and signal space allocation

- 2 System description using the equivalent low-pass signal

- 3 Power and energy of QAM Signals

- 4 Signal waveforms for 4–QAM

- 5 Error probabilities of 4–QAM

- 6 Quadratic QAM signal space constellations

- 7 Other signal space constellations

- 8 Nyquist and root Nyquist QAM systems

- 9 Offset–Quadrature amplitude modulation

- 10 Exercises for the chapter

- 11 References

General description and signal space allocation

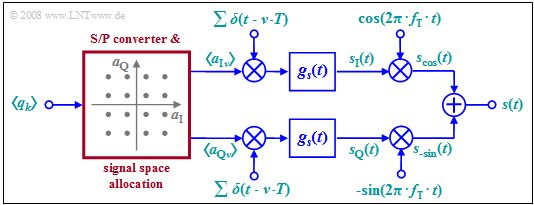

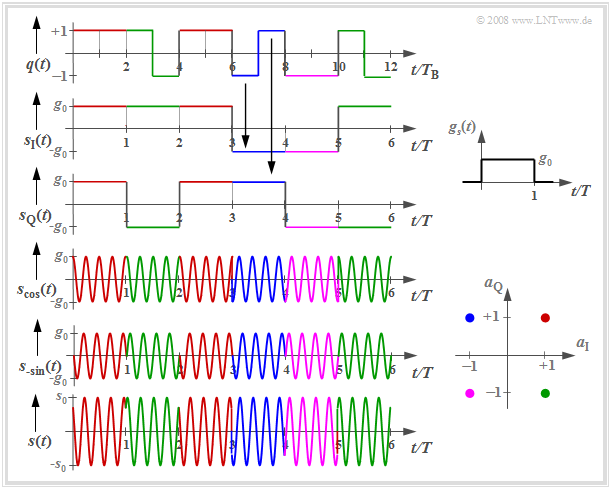

Due to the orthogonality of cosine and (minus) sine, two data streams can be transmitted independently via the same transmission channel. The diagram shows the general circuit schematic.

This very general model can be described as follows:

- The binary source symbol sequence $〈q_k〉$ with bit rate $R_{\rm B}$ is applied to the input. Thus, the time interval between two symbols is $T_{\rm B} = 1/R_{\rm B}$.

- Two multilevel amplitude coefficients $a_{{\rm I}ν}$ and $a_{{\rm Q}ν}$ are derived from each $b$ binary input symbols $q_k$ , where $\rm I$ stands for inphase and $\rm Q$ stands for quadrature component.

- If $b$ is even and the signal space allocation is quadratic, then the coefficients $a_{{\rm I}ν}$ and $a_{{\rm Q}ν}$ can each take on one of the $M = 2^{b/2}$ amplitude values with equal probability. This is then referred to as quadrature amplitude modulation $\rm (QAM)$.

- The example considered in the graph is for $\text{16-QAM}$ with $b = M = 4$ and correspondingly $M^2 =16$ signal space points. For a $\text{256-QAM}$ , $b = 8$ and $M = 16$ would apply: $2^b = M^2 = 256$.

- Next, the coefficients $a_{{\rm I}ν}$ and $a_{{\rm Q}ν}$ are each applied to a Dirac impulse as pulse weights. Thus, after shaping a pulse with the fundamental transmission pulse $g_s(t)$ , the following holds for both branches of the circuit diagram:

- $$s_{\rm I}(t) = \sum_{\nu = - \infty}^{+\infty}a_{\rm I\hspace{0.03cm}\it \nu} \cdot g_s (t - \nu \cdot T)\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{1cm}s_{\rm Q}(t) = \sum_{\nu = - \infty}^{+\infty}a_{\rm Q\hspace{0.03cm}\it \nu} \cdot g_s (t - \nu \cdot T)\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- Note that because of the redundancy-free conversion, the symbol duration $T$ of these signals is larger by a factor of $b$ than the bit duration $T_{\rm B}$ of the binary source signal. In the illustrated example $\text{(16-QAM)}$ , $T = 4 · T_{\rm B}$ holds.

- The QAM transmitted signal $s(t)$ is then the sum of the two signals multiplied by cosine and minus-sine, respectively:

- $$s_{\rm cos}(t) = s_{\rm I}(t) \cdot \cos(2 \pi f_{\rm T} t), \hspace{1cm} s_{\rm -sin}(t) = -s_{\rm Q}(t) \cdot \sin(2 \pi f_{\rm T} t)$$

- $$\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}s(t) = s_{\rm cos}(t)+ s_{\rm -sin}(t) = s_{\rm I}(t) \cdot \cos(2 \pi f_{\rm T} t) - s_{\rm Q}(t) \cdot \sin(2 \pi f_{\rm T} t) \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

$\text{Conclusion:}$ these statements can be summarized as follows:

- The two transmission branches $\rm (I,\ Q)$ can be thought of as two completely separate $M$-step ASK systems that do not interfere with each other as long as all components are optimally designed.

- Quadrature amplitude modulation thus makes it (ideally) possible to double the data rate while maintaining the same quality.

System description using the equivalent low-pass signal

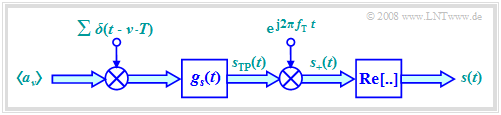

Since the multiplication of $s_{\rm I}(t)$ and $s_{\rm Q}(t)$ , with a cosine and minus-sine oscillation respectively, only causes a shift in the frequency domain and such a shift is a linear operation, the system description can be greatly simplified using the equivalent low-pass signals.

- The graph shows the simplified model in the baseband. This is equivalent to the block diagram considered so far.

- The serial-parallel conversion and the signal space allocation drawn in red in the block diagram are retained. This block is no longer drawn here.

- We also initially disregard the bandpass $H_{\rm BP}(f)$ , which is often introduced for technical reasons.

Please note the following:

- All double arrows in the baseband model denote complex quantities. The operations associated with them should also be understood as complex. For example, the complex amplitude coefficient $a_ν$  combines one inphase and one quadrature coefficient:

- $$a_\nu = a_{\rm I\hspace{0.03cm}\it \nu} + {\rm j} \cdot a_{\rm Q\hspace{0.03cm}\it \nu} \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- The equivalent low-pass representation of the actual, physical and thus per se real transmitted signal $s(t)$ is always complex in QAM and with the partial signals $s_{\rm I}(t)$ and $s_{\rm Q}(t)$ it holds that:

- $$s_{\rm TP}(t) = s_{\rm I}(t) + {\rm j} \cdot s_{\rm Q}(t) = \sum_{\nu = - \infty}^{+\infty} a_\nu \cdot g_s (t - \nu \cdot T)\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- The analytical signal $s_+(t)$ is obtained from $s_{\rm TP}(t)$ by multiplying by the complex exponential function. The physical transmitted signal $s(t)$ ) is then obtained as the real part of $s_+(t)$.

- In order for the signs in the block diagram on the previous page and the sketched baseband model to match, multiplication by the negative sine wave is required in the quadrature branch, as shown in the following calculation:

- $$s(t) = {\rm Re}[s_{\rm +}(t)] = {\rm Re}[s_{\rm TP}(t) \cdot{\rm e}^{{\rm j}2\pi f_{\rm T} t}] $$

- $$\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} s(t) = {\rm Re} \left[\left ( \sum (a_{\rm I\hspace{0.03cm}\it \nu} + {\rm j} \cdot a_{\rm Q\hspace{0.03cm}\it \nu} ) \cdot g_s (t - \nu \cdot T)\right )\left ( \cos(2 \pi f_{\rm T} t) + {\rm j} \cdot \sin(2 \pi f_{\rm T} t) \right )\right]= s_{\rm I}(t) \cdot \cos(2\pi f_{\rm T} t) - s_{\rm Q}(t) \cdot \sin(2 \pi f_{\rm T} t) \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- The influence of the bandpass $H_{\rm BP}(f)$, which in practice often has to be considered at the output of the QAM modulator, can be assigned to the pulse shape filter $g_s(t)$ . If the passband of the bandpass filter is symmetric about $f_{\rm T}$, its low-pass equivalent (in the time domain) $h_{\rm BP→TP}(t)$ is purely real and one can replace $g_s(t)$ with $g_s(t) \star h_{\rm BP→TP}(t)$ in the model.

Power and energy of QAM Signals

As shown in the chapter Equivalent Low-Pass Signal and its Spectral Function in the book "Signal Representation", the power of the transmitted QAM signal $s(t)$ can also be calculated from the equivalent low-pass signal $s_{\rm TP}(t)$ , which is always complex. Thus, it is equally valid to write:

- $$P = \lim_{T_{\rm M} \rightarrow \infty} \frac{\rm 1}{T_{\rm M}}\cdot \int_{-T_{\rm M}/2}^{+T_{\rm M}/2} s^2(t)\,{\rm d} t = {\rm 1}/{2} \cdot \lim_{T_{\rm M} \rightarrow \infty} \frac{\rm 1}{T_{\rm M}}\cdot \int_{-T_{\rm M}/2}^{+T_{\rm M}/2} |s_{\rm TP}(t)|^2\,{\rm d} t \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

In contrast, the energy of the unbounded signals $s(t)$ and $s_{\rm TP}(t)$ is infinite.

However, if we restrict ourselves to a symbol duration $T$, we obtain the energy per symbol:

- $$E_{\rm S} = \frac{{\rm E}[\hspace{0.05cm}|a_{\nu} |^2\hspace{0.05cm}]}{2}\cdot \int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} |g_s(t)|^2\,{\rm d} t = \frac{{\rm E}[|a_{\nu} |^2]}{2}\cdot \int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} |G_s(f)|^2\,{\rm d} f \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

On the other hand, $E_{\rm B} = E_{\rm S}/b$ gives the energy per bit when each binary symbol $b$ is combined to form the complex coefficient $a_\nu$ according to the signal space allocation.

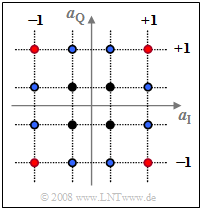

$\text{Example 1:}$ the top graph shows the signal space allocationfor $\text{16-QAM}$, where both the real and imaginary parts of the complex amplitude coefficients $a_ν$ can take one of four values $±1$ as well as $±1/3$ , respectively.

Averaging over the $16$ squared distances to the origin yields:

- $${\rm E}\big[\hspace{0.05cm} \vert a_{\nu}\vert^2 \hspace{0.05cm}\big] \hspace{0.18cm} = \hspace{0.18cm} \frac{4}{16} \cdot (1^2 + 1^2)+ \frac{4}{16} \cdot \left[(1/3 )^2 +(1/3)^2 \right ] + \frac{8}{16} \cdot \left [1^2 + (1/3)^2\right ] $$

- $$\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}{\rm E}\big[\hspace{0.05cm} \vert a_{\nu}\vert^2 \hspace{0.05cm}\big] = {10}/{9}\approx 1.11 \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

In this order, the summands belong to

- the four red,

- the four black, and

- the eight blue dots.

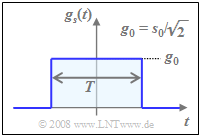

For a NRZ rectangular fundamental transmit pulse $g_s(t)$ with amplitude $g_0$ and symbol duration $T$ , the spectrum $G_s(f)$ is $\rm si$–shaped.

In this case, the following holds true for

- the average energy per symbol:

- $$E_{\rm S} = 1/2 \cdot {\rm E}\big[\hspace{0.05cm}\vert a_{\nu} \vert ^2 \big]\hspace{0.05cm}\cdot g_0^2 \cdot T = {5}/{9}\cdot g_0^2 \cdot T \hspace{0.05cm}\approx 0.555 \cdot g_0^2 \cdot T \hspace{0.05cm},$$

- the average energy per bit:

- $$E_{\rm B} ={E_{\rm S} }/{4}= {5}/{36}\cdot g_0^2 \cdot T \approx 0.139 \cdot g_0^2 \cdot T \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

The "maximum envelope" $s_0$ of the transmitted signal $s(t)$ is larger than the amplitude $g_0$ of the rectangular pulse by a factor of $\sqrt{2}$ (see bottom sketch) and occurs at one of the four red amplitude coefficients, i.e., whenever $\vert a_{\rm I \it ν}\vert = \vert a_{\rm Q \it ν}\vert =1$ .

Signal waveforms for 4–QAM

The following graph shows the signal waveforms of $\rm 4-QAM$, where the coloring corresponds to the signal space allocation defined above.

One can see from these plots:

- the serial-to-parallel conversion of the source signal $q(t)$ into the two component signals 𝑠 $s_{\rm I}(t)$ and $s_{\rm Q}(t)$, each with symbol duration $T = 2T_{\rm B}$ and signal values $±g_0$. Here, $T_{\rm B}$ denotes the bit duration;

- the two carrier frequency modulated signals $s_{\rm cos}(t)$ and $s_{\rm –sin}(t)$ with phase jumps around $±π$:

- $$s_{\rm cos} (t) = s_{\rm I} (t) \cdot \cos(2\pi f_{\rm T}t)\hspace{0.05cm},$$

- $$s_{\rm -sin} (t) = -s_{\rm Q} (t) \cdot \sin(2\pi f_{\rm T}t)\hspace{0.05cm}, $$

- the transmitted signal $s(t) = s_{\rm cos}(t) \ – \ s_{\rm –sin}(t)$ with phase jumps by multiples of $±π/2$;; their envelope is larger than the two component signals by a factor of $\sqrt{2}$ :

- $$s_0 = \sqrt{2} \cdot g_0 \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

- Here, fundamental transmission pulse $g_s(t)$ is assumed to be rectangular between $0$ and $T$ , i.e., asymmetric with respect to $t = 0$, for simplicity of representation.

- The associated spectral function $G_s(f)$ of this causal pulse $g_s(t)$ is complex, though this has no implications in this context.

Error probabilities of 4–QAM

In the earlier section Error probabilities – a brief overview, the bit error probability of binary phase shift keying $\rm BPSK)$ was given, among other things. Now the results are transferred to $\text{4-QAM}$ , where the following conditions still apply:

- a transmit signal with the average energy $E_{\rm B}$ per bit,

- AWGN noise with the (single-sided) noise power density $N_0$,

- the best possible receiver realization using the matched-filter principle.

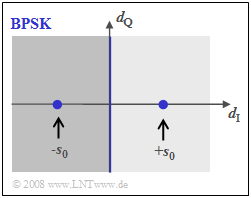

The upper image shows the BPSK phase diagram of the detection signal $d(t)$, i.e., including the matched filter. The distance of the useful signal from the threshold ($d_{\rm Q}$–axis) is $s_0$ at each of the detection times.

Using the additional equations

- $$p_{\rm B} = {\rm Q}\left ( {s_0}/{\sigma_d } \right ), \hspace{0.2cm} E_{\rm B} = {1}/{2} \cdot s_0^2 \cdot T_{\rm B} ,\hspace{0.2cm} \sigma_d^2 = {N_0}/{T_{\rm B} }$$

the BPSK error probability is given by: $$p_{\rm B, \hspace{0.1cm}BPSK} = {\rm Q}\left ( \sqrt{{2 \cdot E_{\rm B}}/{N_0 }} \hspace{0.1cm}\right ) = {1}/{2}\cdot {\rm erfc}\left ( \sqrt{{E_{\rm B}}/{N_0 }} \hspace{0.1cm}\right ).$$

In the $\text{4-QAM}$ corresponding to the image below

- there are two thresholds between the areas with lighter/darker background (blue line) and between the dotted/dashed areas (red line),

- the distance from each threshold is only $g_0$ instead of $s_0$,

- but the noise power $\sigma_d^2$ is also only half as large compared to BPSK because of the halved symbol rate in each sub-branch.

Thus, with the equations

- $$p_{\rm B} = {\rm Q}\left ( {g_0}/{\sigma_d } \right ), \hspace{0.2cm}g_{0} = {s_0}/{\sqrt{2}}, \hspace{0.2cm}E_{\rm B} = {1}/{2} \cdot s_0^2 \cdot T_{\rm B} ,\hspace{0.2cm} \sigma_d^2 = {N_0}(2 \cdot T_{\rm B} )$$

one obtains the exact same result for the 4-QAM error probability as for BPSK:

- $$p_{\rm B, \hspace{0.1cm}4-QAM} = {\rm Q}\left ( \sqrt{{2 \cdot E_{\rm B}}/{N_0 }} \hspace{0.1cm}\right ) = {1}/{2}\cdot {\rm erfc}\left ( \sqrt{{E_{\rm B}}/{N_0 }} \hspace{0.1cm}\right ).$$

$\text{Conclusion:}$

- Under ideal conditions, $\text{4-QAM}$ has the same error probability as $\text{BPSK}$, although twice the amount of information can be transmitted.

- However, if the conditions are no longer ideal - for example, if there is an unwanted phase offset between the transmitter and receiver - there is much more degradation with 4-QAM than with BPSK.

- This case is considered in more detail in the section Error probabilities for 4–QAM and 4–PSK of the book "Digital Signal Transmission".

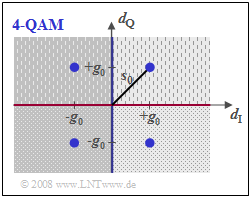

Quadratic QAM signal space constellations

The following figure shows the signal space constellations of $\text{4-QAM}$, $\text{16-QAM}$ and $\text{64-QAM}$.

- With the axis labels chosen here, the images also describe the detectable useful signal (at the detection times) in the equivalent low-pass range.

- Also plotted are the various decision regions assigned to the noisy detection signal.

- The arrows indicate when decision regions are extended to infinity.

The images refer only to the detection time points and apply to all Nyquist systems

- such as the rectangular-rectangular configuration (the fundamental transmission pulse and receiver filter impulse response are rectangular)

- or a Root cosine rolloff Nyquist system.

However, the transitions between the individual points (outside the detection times), which are not shown here, very much depend on the selected Nyquist system.

Further things to note about these representations:

- With a true QAM structure - i.e., a square or at least rectangular signal space configuration - the "two-dimensional" detection process can be solved in a simplified way by two "one-dimensional" detection processes.

- $\text{16-QAM}$ is thus nothing more than the parallel transmission of two digital signals with $M = 4$ amplitude levels each.

- For $\text{64-QAM}$ , $M = 8$ would apply analogously, and for $\text{256-QAM}$ , the "one-dimensional" number of levels is $M = 16$.

- All the properties for redundancy-free multilevel signals mentioned in the chapter [[Digital_Signal_Transmission/Redundancy-Free_Coding|Redundancy-free Coding] of the book "Digital signal transmission" also apply here, although the addition of the orthogonal carrier frequency signals must still be suitably taken into account.

Other signal space constellations

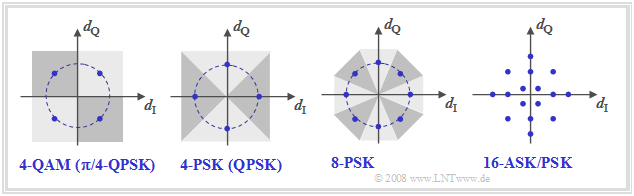

The graphic shows further signal space constellations. On the left, 4-QAM is shown according to the previous description. The constellation to the right indicates a four-level phase modulation, which we call "4-PSK" or "QPSK". A comparison of these two diagrams on the left shows:

- The variant referred to here as QPSK (Quaternary Phase Shift Keying ) uses the phase positions $0^\circ$, $90^\circ$, $180^\circ$ and $270^\circ$.

- From the plotted decision regions, it can be seen that the detection cannot be attributed to two binary decisions here.

- The 4–QAM (links) can also be understood as a four-stage phase modulation $($phase positions $±45^\circ$, $±135^\circ)$.

- Compared to QPSK, a rotation of $±45^\circ$ $(π/4)$ ⇒ 4–QAM is often called ${\rm π/4}\text{–QPSK}$ .

- Similarly to how one arrives at DPSK by pre-coding BPSK, 4-PSK can also be extended to 4-DPSK, thereby facilitating demodulation.

- This was used, for example, for data transmission over telephone channels in accordance with the CCITT recommendation "V26" $($carrier frequency $\text{1800 Hz}$, data rate $\text{2400 bit/s)}$.

The two diagrams on the right show higher-level modulation methods:

- The 8–PSK (or 8–DPSK) allows a data rate of up to $\text{4800 bit/s}$ for the telephone channel according to CCITT recommendation "V27".

- Recommendation "V29" enables a hybrid modulation in the form of 16-ASK/PSK, which enables data rates of up to $\text{9600 bit/s}$ for permanently connected lines.

Nyquist and root Nyquist QAM systems

So far in this chapter, for reasons of representation, the basic rectangular transmission pulse has always been assumed. In practice, however, a root-Nyquist characteristic is usually used according to the description in the book "Digital Signal Transmission". Briefly, these systems can be characterized as follows:

- The receiver frequency response $H_{\rm E}(f)$ is chosen here to be equal in shape to the (normalized) transmission pulse spectrum $H_{\rm S}(f)$ , which leads to the smallest possible error probability under the constraints of power limitations (that is: at constant average transmit power).

- The overall frequency response $H_{\rm Nyq}(f) = H_{\rm S}(f) · H_{\rm E}(f)$ satisfies the first Nyquist criterion, so there is no impulse interference at the receiver. Thus, $H_{\rm S}(f)$ and $H_{\rm E}(f)$ each have a root Nyquist characteristic.

- For the frequency response $H_{\rm Nyq}(f)$ , one uses a cosine rolloff low-pass $H_{\rm CRO}(f)$ with equivalent bandwidth $Δf_{\rm CRO} = 1/T$ and freely chosen rolloff factor $(0 ≤ r ≤ 1)$. The interactive Frequency and Impulse Responses applet illustrates the frequency response and impulse response of this low-pass filter.

- The advantage of these root-Nyquist systems is the much smaller bandwidth $(1 + r)/T$ compared to the previously considered configuration with rectangular $g_s(t)$ and rectangular $h_{\rm E}(t)$, whose spectrum is (theoretically) infinitely extended.

- In terms of error probability, nothing changes compared to the rectangular-rectangular configuration because the fundamental pulse $g_d(t)$ has equidistant zero crossings before the decision, thus avoiding impulse interference.

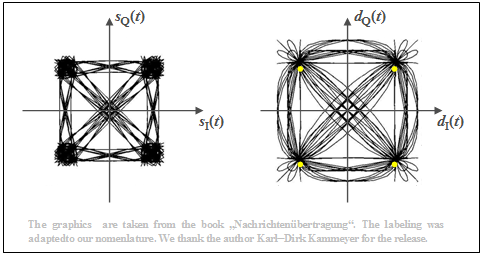

The graph shows phase diagrams for this case, taken from the book [Kam04][1] . The rolloff factor is $r = 0.5$. From these plots, one can see:

- The right plot shows the detection signals in the $\rm I$– and $\rm Q$ branches after the root Nyquist receiver filters in a 2D representation. The corresponding spectra each have cosine-shaped slopes around the Nyquist frequency $f_{\rm Nyq} = 1/(2T)$.

- At the detection times, only the four points plotted in yellow are possible in the phase diagram. The transitions in between are diverse. It should be noted that only a few lines pass through the coordinate null point.

- Shown on the left are the two transmitted signals in the equivalent low-pass region, $s_{\rm I}(t) = {\rm Re}\big[s_{\rm TP}(t)\big]$ and $s_{\rm Q}(t) = {\rm Im}\big[s_{\rm TP}(t)\big]$. Due to the root-Nyquist spectral shaping, there is impulse interference at the transmitter, which means that the equivalent low-pass signal $s_{\rm TP}(t) = s_{\rm I}(t) + {\rm j} · s_{\rm Q}(t)$ is also not limited to four points at the detection times.

- The magnitude $|s_{\rm TP}(t)|$ - that is, the distance from zero - indicates the envelope of the 4-QAM signal. It can be clearly seen from the left diagram that there are strong amplitude dips especially with phase changes around $π$ , since then $s_{\rm TP}(t)$ often also assumes (complex) values close to zero.

Offset–Quadrature amplitude modulation

Taking the equations for the $\text{4–QAM}$ $($or $π/4\text{–QPSK)}$ as our starting point, we arrive at the $\text{Offset–4–QAM}$, which we simplify by calling $\text{Offset–QPSK}$ . Here the transmit signal is given by:

- $$s(t) =s_{\rm I}(t) \cdot \cos(2 \pi f_{\rm T} t) - s_{\rm Q}(t) \cdot \sin(2 \pi f_{\rm T} t),$$

- $$\hspace{0.3cm}\Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm}s_{\rm I}(t) = \sum_{\nu = - \infty}^{+\infty}a_{\rm I\hspace{0.03cm}\it \nu} \cdot g_s (t - \nu \cdot T)\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.5cm} s_{\rm Q}(t) = \sum_{\nu = - \infty}^{+\infty}a_{\rm Q\hspace{0.03cm}\it \nu} \cdot g_s (t -{T}/{2} - \nu \cdot T)\hspace{0.05cm}.$$

The sole but decisive difference is the time shift of the quadrature component with respect to the in-phase component by half a symbol duration $(T/2)$. This has the advantage that

- the phase function does not pass through zero, and

- the envelope $|s_{\rm TP}(t)|$ therefore fluctuates much less.

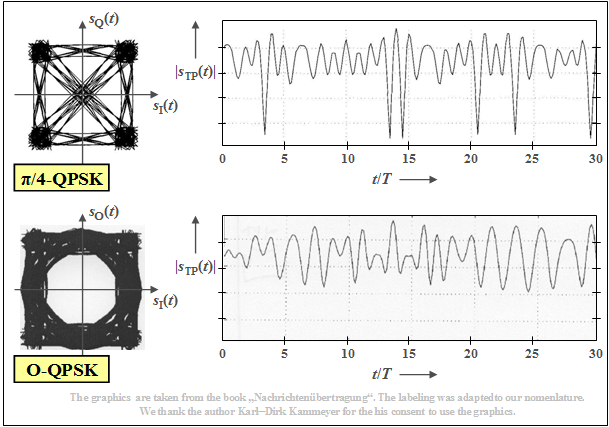

$\text{Example 2:}$ The upper graph shows

- the phase diagram for $π/4\hspace{-0.05cm}-\hspace{-0.05cm}\text{QPSK}$ on the left,

- on the right, a typical envelope progression, based on a root Nyquist transmission spectrum with the rolloff factor $r = 0.5$ , as in the last section.

The lower images show that the $\text{Offset – QPSK}$ has significantly better properties with respect to the envelope (less severe signal dips).

Essential properties of 4-QAM/QPSK and Offset-QPSK can be illustrated with the interactive applet QPSK and Offset-QPSK , where the fundamental impulse can be alternatively chosen as

- a rectangular impulse,

- a cosine impulse,

- a Nyquist impulse,

- a root Nyquist impulse.

Exercises for the chapter

Aufgabe 4.10: Signalverläufe der 16–QAM

Aufgabe 4.10Z: Signalraumkonstellation der 16–QAM

Aufgabe 4.11: Frequenzbereichsbetrachtung der 4–QAM

Aufgabe 4.11Z: Fehlerwahrscheinlichkeit bei QAM

Aufgabe 4.12: Wurzel–Nyquist–Systeme

Aufgabe 4.12Z: Nochmals 4–QAM–Systeme

References

- ↑ Kammeyer, K.D.: Nachrichtenübertragung. Stuttgart: B.G. Teubner, 4. Auflage, 2004.