Difference between revisions of "Information Theory/General Description"

| (93 intermediate revisions by 9 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | |||

{{Header | {{Header | ||

| − | |Untermenü= | + | |Untermenü=Source Coding - Data Compression |

| − | |Vorherige Seite= | + | |Vorherige Seite=Natural Discrete Sources |

|Nächste Seite=Komprimierung nach Lempel, Ziv und Welch | |Nächste Seite=Komprimierung nach Lempel, Ziv und Welch | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | == # OVERVIEW OF THE SECOND MAIN CHAPTER # == | |

| + | <br> | ||

| + | Shannon's Information Theory is applied, for example, in the »'''Source coding'''« of digital (i.e. discrete and discrete-time) message sources. In this context, one also speaks of »'''Data compression'''«. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Attempts are made to reduce the redundancy of natural digital sources such as measurement data, texts, or voice and image files (after digitization) by recoding them, so that they can be stored and transmitted more efficiently. | ||

| + | *In most cases, source encoding is associated with a change of the symbol set size. in the following, the output sequence is always binary. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The following is a detailed discussion of: | ||

| − | + | :*The different destinations of »source coding«, »channel coding« and »line coding«, | |

| + | :*»lossy encoding methods« for analog sources, for example GIF, TIFF, JPEG, PNG, MP3, | ||

| + | :*the »source encoding theorem«, which specifies a limit for the average code word length, | ||

| + | :*the frequently used data compression according to »Lempel, Ziv and Welch«, | ||

| + | :*the »Huffman code« as the best known and most efficient form of entropy coding, | ||

| + | :*the »Shannon-Fano code« as well as the »arithmetic coding« - both belong to the class of entropy encoders as well, | ||

| + | :*the »run-length coding« (RLC) and the »Burrows-Wheeler transformation« (BWT). | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | == Source coding - Channel coding - Line coding == | |

| − | + | <br> | |

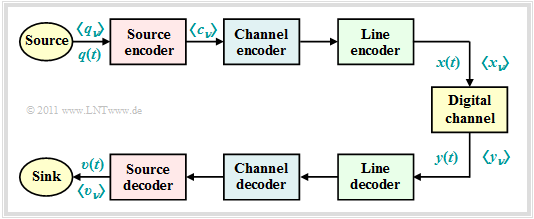

| − | + | For the descriptions in this second chapter we consider the following model of a digital transmission system: | |

| − | + | [[File:EN_Inf_T_2_1_S1_v2.png|right|frame|Simplified model of a digital transmission system]] | |

| + | *The source signal $q(t)$ can be analog as well as digital, just like the sink signal $v(t)$. All other signals in this block diagram, even those not explicitly named here, are digital. | ||

| − | + | *In particular, also the signals $x(t)$ and $y(t)$ at the input and output of the "digital channel" are digital and can therefore also be described completely by the symbol sequences $〈x_ν〉$ and $〈y_ν〉$. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *The "digital channel" includes not only the transmission medium and interference (noise) but also components of the transmitter $($modulator, transmitter pulse shaper, etc.$)$ and the receiver $($demodulator, receiver filter, detector, decision'''$)$. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | *The chapter [[Digital_Signal_Transmission/Parameters of Digital Channel Models|"Parameters of Digital Channel Models"]] in the book "Digital Signal Transmission" describes the modeling of the "digital channel". | ||

| + | <br clear=all> | ||

| + | As can be seen from this block diagram, there are three different types of coding, depending on the target direction. Each of which is realized by the "encoder" on the transmission side and the corresponding "decoder" at the receiver: | ||

| − | + | ⇒ Task of the »'''source coding'''« is the reduction of redundancy for data compression, as it is used for example in image coding. By using correlations between the individual points of an image or between the brightness values of a pixel at different times (for moving picture sequences) procedures can be developed which lead to a noticeable reduction of the amount of data (measured in bit or byte) with nearly the same picture quality. A simple example is the »differential pulse code modulation« (DPCM). | |

| − | + | ⇒ With »'''channel coding'''« on the other hand, a noticeable improvement of the transmission behavior is achieved by using a redundancy specifically added at the transmitter to detect and correct transmission errors at the receiver side. Such codes, whose most important representatives are »block codes«, »convolutional codes« and »turbo codes«, are of great importance, especially for heavily disturbed channels. The greater the relative redundancy of the encoded signal, the better the correction properties of the code, but at a reduced payload data rate. | |

| − | + | ⇒ »'''Line coding'''« is used to adapt the transmitted signal $x(t)$ to the spectral characteristics of the channel and the receiving equipment by recoding the source symbols. For example, in the case of an (analog) transmission channel over which no direct signal can be transmitted, for which thus $H_{\rm K}(f = 0) = 0$, it must be ensured by line coding that the encoded sequence does not contain long sequences of the same polarity. | |

| + | The focus of this chapter is on lossless source coding, which generates a data-compressed encoded sequence $〈c_ν〉$ starting from the source symbol sequence $〈q_ν〉$ and based on the results of information theory. | ||

| − | { | + | * Channel coding is the subject of a separate book in our tutorial with the following [[Channel_Coding|$\text{content}$]] . |

| − | + | *The channel coding is discussed in detail in the chapter "Coded and multilevel transmission" of the book [[Digital_Signal_Transmission|"Digital Signal Transmission"]] . | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | <u>Note:</u> We uniformly use "$\nu$" here as a control variable of a symbol sequence. Normally, for $〈q_ν〉$, $〈c_ν〉$ and $〈x_ν〉$ different indices should be used if the rates do not match. | ||

| − | |||

| + | == Lossy source coding for images== | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | For digitizing analog source signals such as speech, music or pictures, only lossy source coding methods can be used. Even the storage of a photo in [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/BMP_file_format $\text{BMP}$] format is always associated with a loss of information due to sampling, quantization and the finite color depth. | ||

| − | + | However, there are also a number of compression methods for images that result in much smaller image files than "BMP", for example: | |

| − | * | + | *[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/GIF $\text{GIF}$] ("Graphics Interchange Format"), developed by Steve Wilhite in 1987. |

| − | * | + | *[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/JPEG $\text{JPEG}$] - a format that was introduced in 1992 by the "Joint Photography Experts Group" and is now the standard for digital cameras. Ending: "jpeg" or "jpg". |

| − | + | *[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/TIFF $\text{TIFF}$] ("Tagged Image File Format"), around 1990 by Aldus Corp. (now Adobe) and Microsoft, still the quasi-standard for print-ready images of the highest quality. | |

| + | *[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portable_Network_Graphics $\text{PNG}$] ("Portable Network Graphics"), designed in 1995 by T. Boutell and T. Lane as a replacement for the patent-encumbered GIF format, is less complex than TIFF. | ||

| − | + | These compression methods partly use | |

| − | + | *vector quantization for redundancy reduction of correlated pixels, | |

| − | + | *at the same time the lossless compression algorithms according to [[Information_Theory/Entropy_Coding_According_to_Huffman#The_Huffman_algorithm|$\text{Huffman}$]] and [[Information_Theory/Compression According to Lempel, Ziv and Welch|$\text{Lempel/Ziv}$]], | |

| − | * | + | *possibly also transformation coding based on DFT ("Discrete Fourier Transform") and DCT ("Discrete Cosine Transform"), |

| − | + | *then quantization and transfer in the transformed range. | |

| − | * | ||

| − | * | ||

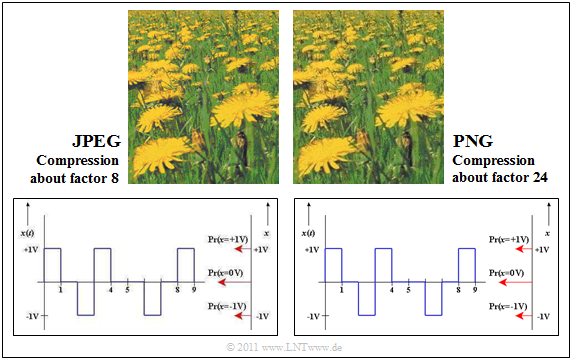

| − | + | We now compare the effects of two compression methods on the subjective quality of photos and graphics, namely: | |

| + | *$\rm JPEG$ $($with compression factor $8)$, and | ||

| + | *$\rm PNG$ $($with compression factor $24)$. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | {{GraueBox|TEXT= | ||

| + | $\text{Example 1:}$ | ||

| + | In the upper part of the graphic you can see two compressions of a photo. | ||

| + | [[File:EN_Inf_T_2_1_S2.png|right|frame|Compare JPEG and PNG compression]] | ||

| + | The format $\rm JPEG$ (left image) allows a compression factor of $8$ to $15$ with (nearly) lossless compression. | ||

| + | *Even with the compression factor $35$ the result can still be called "good". | ||

| + | *For most consumer digital cameras, "JPEG" is the default storage format. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The image shown on the right was compressed with $\rm PNG$. | |

| + | *The quality is similar to the JPEG result, although the compression is about $3$ stronger. | ||

| + | *In contrast, PNG achieves a worse compression result than JPEG if the photo contains a lot of color gradations. | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | PNG is also better suited for line drawings with captions than JPEG (compare the lower images). | |

| + | *The quality of the JPEG compression (on the left) is significantly worse than the PNG result, although the resulting file size is about three times as large. | ||

| + | *Especially fonts look "washed out". | ||

| + | <br clear=all> | ||

| + | <u>Note:</u> Due to technical limitations of $\rm LNTwww$ all graphics had to be saved as "PNG". | ||

| + | *In the above graphic, "JPEG" means the PNG conversion of a file previously compressed with "JPEG". | ||

| + | *However, the associated loss is negligible. }} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | == Lossy source coding for audio signals== | |

| − | * | + | <br> |

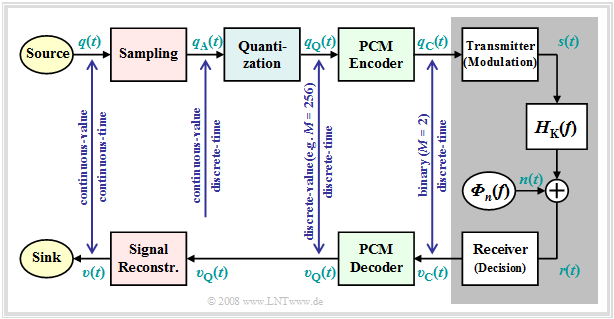

| − | * | + | A first example of source coding for speech and music is the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pulse-code_modulation "pulse-code modulation"] $\rm (PCM)$, invented in 1938, which extracts the encoded sequence $〈c_ν〉 $ from an analog source signal $q(t)$, corresponding to the three processing blocks |

| − | * | + | [[File:EN_Mod_T_4_1_S1_v2.png|right|frame|Prinzip der Pulscodemodulation (PCM)]] |

| + | *Sampling, | ||

| + | *Quantization, | ||

| + | *PCM encoding. | ||

| − | + | The graphic illustrates the PCM principle. A detailed description of the picture can be found on the first sections of the chapter [[Modulation_Methods/Pulse Code Modulation|"Pulse-code modulation"]] in the book "Modulation Methods". | |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Because of the necessary band limitation and quantization, this transformation is always lossy. That means | ||

| + | *The encoded sequence $〈c_ν〉$ has less information than the source signal $q(t)$. | ||

| + | *The sink signal $v(t)$ is fundamentally different from $q(t)$. | ||

| + | *Mostly, however, the deviation is not very large. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | We will now mention two transmission methods based on pulse code modulation as examples. | |

| − | + | <br clear=all> | |

| − | + | {{GraueBox|TEXT= | |

| − | $$ | + | $\text{Example 2:}$ |

| + | The following data is taken from the [[Examples_of_Communication_Systems/Entire_GSM_Transmission_System#Speech_and_data_transmission_components|$\text{GSM specification}$]]: | ||

| + | *If a speech signal is spectrally limited to the bandwidth $B = 4 \, \rm kHz$ ⇒ sampling rate $f_{\rm A} = 8 \, \rm kHz$ with a quantization of $13 \, \rm bit$ ⇒ number of quantization levels $M = 2^{13} = 8192$ a binary data stream of data rate $R = 104 \, \rm kbit/s$ results. | ||

| + | *The quantization noise ratio is then $20 \cdot \lg M ≈ 78 \, \rm dB$. | ||

| + | *For quantization with $16 \, \rm bit$ this increases to $96 \, \rm dB$. At the same time, however, the required data rate increases to $R = 128 \, \rm kbit/s$. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The following (German language) interactive SWF applet illustrates the effects of a bandwidth limitation:<br> [[Applets:Bandwidth Limitation|"Einfluss einer Bandbegrenzung bei Sprache und Musik"]] ⇒ "Impact of a Bandwidth Limitation for Speech and Music" .}} | |

| − | |||

| − | : | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | {{GraueBox|TEXT= | |

| − | + | $\text{Example 3:}$ | |

| − | + | The standard [[Examples_of_Communication_Systems/General_Description_of_ISDN|$\text{ISDN}$]] ("Integrated Services Digital Network") for telephony via two-wire line is also based on the PCM principle, whereby each user is assigned two B-channels (''Bearer Channels'' ) with $64 \, \rm kbit/s$ ⇒ $M = 2^{8} = 256$ and a D-channel (''Data Channel'' ) with $ 16 \, \rm kbit/s$. | |

| + | *The net data rate is thus $R_{\rm net} = 144 \, \rm kbit/s$. | ||

| + | *In consideration of the channel coding and the control bits (required for organizational reasons), the ISDN gross data rate of $R_{\rm gross} = 192 \, \rm kbit/s$.}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In mobile communications, very high data rates often could not (yet) be handled. In the 1990s, speech coding procedures were developed that led to data compression by the factor $8$ and more. From today's point of view, it is worth mentioning: | |

| + | *The [[Examples_of_Communication_Systems/Speech_Coding#Half_Rate_Vocoder_and_Enhanced_Full_Rate_Codec|$\text{Enhanced Full Rate Codec}$]] $\rm (EFR)$, which extracts exactly $244 \, \rm bit$ for each speech frame of $20\, \rm ms$ $($Data rate: $12. 2 \, \rm kbit/s)$; <br> this data compression of more than the factor $8$ is achieved by stringing together several procedures: | ||

| + | :# Linear Predictive Coding $\rm (LPC$, short term prediction$)$, | ||

| + | :# Long Term Prediction $\rm (LTP)$, | ||

| + | :# Regular Pulse Excitation $\rm (RPE)$. | ||

| + | *The [[Examples_of_Communication_Systems/Speech_Coding#Adaptive_Multi_Rate_Codec|$\text{Adaptive Multi Rate Codec}$]] $\rm (AMR)$ based on [[Examples_of_Communication_Systems/Voice Coding#Algebraic_Code_Excited_Linear_Prediction|$\rm ACELP$]] ("Algebraic Code Excited Linear Prediction") and several modes between $12. 2 \, \rm kbit/s$ $\rm (EFR)$ and $4.75 \, \rm kbit/s$ so that improved channel coding can be used in case of poorer channel quality. | ||

| + | *The [[Examples_of_Communication_Systems/Speech_Coding#Various_speech_coding_methods|$\text{Wideband-AMR}$]] $\rm (WB-AMR)$ with nine modes between $6.6 \, \rm kbit/s$ and $23.85 \, \rm kbit/s$. This is used with [[Examples_of_Communication_Systems/General_Description_of_UMTS|$\text{UMTS}$]] and is suitable for broadband signals between $200 \, \rm Hz$ and $7 \, \rm kHz$. Sampling is done with $16 \, \rm kHz$, quantization with $4 \, \rm bit$. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | All these compression methods are described in detail in the chapter [[Examples_of_Communication_Systems/Voice Coding|"Speech Coding"]] of the book "Examples of Communication Systems" The (German language) audio module [[Applets:Quality of different voice codecs (Applet)|"Qualität verschiedener Sprach-Codecs"]] ⇒ "Quality of different voice codecs" allows a subjective comparison of these codecs. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==MPEG-2 Audio Layer III - short "MP3" == | |

| + | <br> | ||

| + | Today (2015) the most common compression method for audio files is [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MP3 $\text{MP3}$]. This format was developed from 1982 on at the Fraunhofer Institute for Integrated Circuits (IIS) in Erlangen under the direction of Professor [https://www.tnt.uni-hannover.de/en/staff/musmann/ $\text{Hans-Georg Musmann}$] in collaboration with the Friedrich Alexander University Erlangen-Nuremberg and AT&T Bell Labs. Other institutions are also asserting patent claims in this regard, so that since 1998 various lawsuits have been filed which, to the authors' knowledge, have not yet been finally concluded. | ||

| − | {{ | + | In the following some measures are called, which are used with "MP3", in order to reduce the data quantity in relation to the raw version in the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/WAV $\text{wav}$]-format. The compilation is not complete. A comprehensive representation about this can be found for example in a [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MP3 $\text{Wikipedia article}$]. |

| − | + | *The audio compression method "MP3" uses among other things psychoacoustic effects of perception. So a person can only distinguish two sounds from each other from a certain minimum difference in pitch. One speaks of so-called "masking effects". | |

| + | *Using the masking effects, signal components that are less important for the auditory impression are stored with less bits (reduced accuracy). A dominant tone at $4 \, \rm kHz$ can, for example, cause neighboring frequencies to be of only minor importance for the current auditory sensation up to $11 \, \rm kHz$. | ||

| + | *The greatest advantage of MP3 coding, however, is that the sounds are stored with just enough bits so that the resulting [[Modulation_Methods/Pulse_Code_Modulation#Quantization_and_quantization_noise|$\text{quantization noise}$]] is still masked and is not audible. | ||

| + | *Other MP3 compression mechanisms are the exploitation of the correlations between the two channels of a stereo signal by difference formation as well as the [[Information_Theory/Entropy Coding According to Huffman|$\text{Huffman Coding}$]] of the resulting data stream. Both measures are lossless. | ||

| − | |||

| + | A disadvantage of the MP3 coding is that with strong compression also "important" frequency components are unintentionally captured and thus audible errors occur. Furthermore it is disturbing that due to the blockwise application of the MP3 procedure gaps can occur at the end of a file. A remedy is the use of the so-called [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/LAME $\text{LAME coder}$] and a corresponding player. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | $$\ | + | ==Description of lossless source encoding – Requirements== |

| + | <br> | ||

| + | In the following, we only consider lossless source coding methods and make the following assumptions: | ||

| + | *The digital source has the symbol set size $M$. For the individual source symbols of the sequence $〈q_ν〉$ applies with the symbol set $\{q_μ\}$: | ||

| + | |||

| + | :$$q_{\nu} \in \{ q_{\mu} \}\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}\mu = 1, \hspace{0.05cm}\text{...} \hspace{0.05cm}, M \hspace{0.05cm}. $$ | ||

| + | |||

| + | The individual sequence elements $q_ν$ may can be "statistically independent" or "statistically dependent". | ||

| + | * First we consider »'''discrete sources without memory'''«, which are fully characterized by the symbol probabilities alone, for example: | ||

| + | :$$M = 4\text{:} \ \ \ q_μ \in \{ {\rm A}, \ {\rm B}, \ {\rm C}, \ {\rm D} \}, \hspace{3.0cm} \text{with the probabilities}\ p_{\rm A},\ p_{\rm B},\ p_{\rm C},\ p_{\rm D},$$ | ||

| + | :$$M = 8\text{:} \ \ \ q_μ \in \{ {\rm A}, \ {\rm B}, \ {\rm C}, \ {\rm D},\ {\rm E}, \ {\rm F}, \ {\rm G}, \ {\rm H} \}, \hspace{0.5cm} \text{with the probabilities }\ p_{\rm A},\hspace{0.05cm}\text{...} \hspace{0.05cm} ,\ p_{\rm H}.$$ | ||

| − | { | + | *The source encoder replaces the source symbol $q_μ$ with the code word $\mathcal{C}(q_μ)$, <br>consisting of $L_μ$ code symbols of a new alphabet with the symbol set size $D$ $\{0, \ 1$, ... , $D - 1\}$. This gives the »'''average code word length'''«: |

| − | |||

| − | $$ | + | :$$L_{\rm M} = \sum_{\mu=1}^{M} \hspace{0.1cm} p_{\mu} \cdot L_{\mu} \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}{\rm with} \hspace{0.2cm}p_{\mu} = {\rm Pr}(q_{\mu}) \hspace{0.05cm}. $$ |

| − | + | {{GraueBox|TEXT= | |

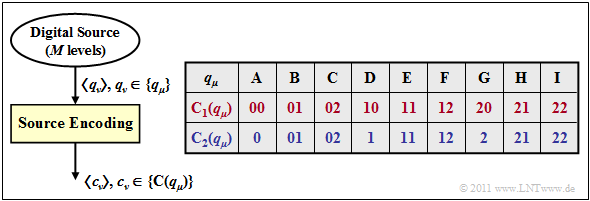

| + | $\text{Example 4:}$ We consider two different types of source encoding, each with parameters $M = 9$ and $D = 3$. | ||

| − | + | [[File:EN_Inf_T_2_1_S3_v2.png|right|frame|Two examples of source encoding]] | |

| + | *In the first encoding $\mathcal{C}_1(q_μ)$ according to line 2 (red) of the table, each source symbol $q_μ$ is replaced by two ternary symbols $(0$, $1$ or $2)$. Here we have for example the mapping: | ||

| + | : $$\rm A C F B I G \ ⇒ \ 00 \ 02 \ 12 \ 01 \ 22 \ 20.$$ | ||

| + | *With this coding, all code words $\mathcal{C}_1(q_μ)$ with $1 ≤ μ ≤ 6$ have the same length $L_μ = 2$. Thus, the average code word length is $L_{\rm M} = 2$. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *For the second, the blue source encoder holds $L_μ ∈ \{1, 2 \}$. Accordingly, the average code word length $L_{\rm M}$ will be less than two code symbols per source symbol. For example, the mapping: | |

| + | : $$\rm A C F B I G \ ⇒ \ 0 \ 02 \ 12 \ 01 \ 22 \ 2.$$ | ||

| + | |||

| + | *It is obvious that this encoded sequence cannot be decoded unambiguously, since the symbol sequence naturally does not include the spaces inserted in this text for display reasons. }} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==Kraft–McMillan inequality - Prefix-free codes == | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | Binary codes for compressing a memoryless discrete source are characterized by the fact that the individual symbols are represented by encoded sequences of different lengths: | ||

| − | $$ | + | :$$L_{\mu} \ne {\rm const.} \hspace{0.4cm}(\mu = 1, \hspace{0.05cm}\text{...} \hspace{0.05cm}, M ) \hspace{0.05cm}.$$ |

| − | + | Only then it is possible, | |

| − | + | *that the '''average code word length becomes minimal''', | |

| − | + | *if the '''source symbols are not equally probable'''. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | To enable a unique decoding, the code must also be "prefix-free". | |

| + | {{BlaueBox|TEXT= | ||

| + | $\text{Definition:}$ The property »'''prefix-free'''« indicates that no code word may be the prefix (beginning) of a longer code word. Such a code word is immediately decodable.}} | ||

| − | = | + | *The blue code in [[Information_Theory/General_Description#Description_of_lossless_source_encoding_.E2.80.93_Requirements|$\text{Example 4}$]] is not prefix-free. For example, the encoded sequence "01" could be interpreted by the decoder as $\rm AD$ but also as $\rm B$. |

| + | *The red code, on the other hand, is prefix-free, although prefix freedom would not be absolutely necessary here because of $L_μ = \rm const.$ | ||

| − | + | {{BlaueBox|TEXT= | |

| − | + | $\text{Without proof:}$ | |

| − | + | The necessary »'''condition for the existence of a prefix-free code'''« was specified by Leon Kraft in his Master Thesis 1949 at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT): | |

| − | + | ||

| + | :$$\sum_{\mu=1}^{M} \hspace{0.2cm} D^{-L_{\mu} } \le 1 \hspace{0.05cm}.$$}} | ||

| − | + | {{GraueBox|TEXT= | |

| + | $\text{Example 5:}$ | ||

| + | If you check the second (blue) code of [[Information_Theory/General_Description#Description_of_lossless_source_encoding_.E2.80.93_Requirements|$\text{Example 4}$]] with $M = 9$ and $D = 3$, you get: | ||

| − | $$ | + | :$$3 \cdot 3^{-1} + 6 \cdot 3^{-2} = 1.667 > 1 \hspace{0.05cm}.$$ |

| − | + | From this you can see that this code cannot be prefix-free. }} | |

| − | {{ | + | {{GraueBox|TEXT= |

| − | + | $\text{Example 6:}$ Let's now look at the binary code | |

| + | |||

| + | :$$\boldsymbol{\rm A } \hspace{0.15cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.15cm} 0 | ||

| + | \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}\boldsymbol{\rm B } \hspace{0.15cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.15cm} 00 | ||

| + | \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}\boldsymbol{\rm C } \hspace{0.15cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.15cm} 11 | ||

| + | \hspace{0.05cm}, $$ | ||

| + | |||

| + | it is obviously not prefix-free. The equation | ||

| − | $$ | + | :$$1 \cdot 2^{-1} + 2 \cdot 2^{-2} = 1 $$ |

| − | {{ | + | does not mean that this code is actually prefix-free, it just means that there is a prefix-free code with the same length distribution, for example |

| + | |||

| + | :$$\boldsymbol{\rm A } \hspace{0.15cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.15cm} 0 | ||

| + | \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}\boldsymbol{\rm B } \hspace{0.15cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.15cm} 10 | ||

| + | \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}\boldsymbol{\rm C } \hspace{0.15cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.15cm} 11 | ||

| + | \hspace{0.05cm}.$$}} | ||

| − | + | == Source coding theorem== | |

| + | <br> | ||

| + | We now look at a redundant discrete source with the symbol set $〈q_μ〉$, where the control variable $μ$ takes all values between $1$ and the symbol set size $M$. The source entropy $H$ is smaller than $H_0= \log_2 \hspace{0.1cm} M$. | ||

| + | The redundancy $(H_0- H)$ is either caused by | ||

| + | *not equally probable symbols ⇒ $p_μ ≠ 1/M$, and/or | ||

| + | *statistical bonds within the sequence $〈q_\nu〉$. | ||

| − | { | + | |

| − | + | A source encoder replaces the source symbol $q_μ$ with the code word $\mathcal{C}(q_μ)$, consisting of $L_μ$ binary symbols (zeros or ones). This results in an average code word length: | |

| − | $$ | + | :$$L_{\rm M} = \sum_{\mu=1}^{M} \hspace{0.2cm} p_{\mu} \cdot L_{\mu} \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}{\rm with} \hspace{0.2cm}p_{\mu} = {\rm Pr}(q_{\mu}) \hspace{0.05cm}. $$ |

| − | \ | ||

| − | + | For the source encoding task described here the following requirement can be specified: | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | {{BlaueBox|TEXT= | |

| − | + | $\text{Theorem:}$ | |

| − | + | For the possibility of a complete reconstruction of the sent string from the binary sequence it is sufficient, but also necessary, that for encoding on the transmitting side at least $H$ binary symbols per source symbol are used. | |

| − | \ | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | *The average code word length $L_{\rm M}$ cannot be smaller than the entropy $H$ of the source symbol sequence: $L_{\rm M} \ge H \hspace{0.05cm}. $ | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *This regularity is called »'''Source Coding Theorem'''«, which goes back to [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Claude_Shannon $\text{Claude Elwood Shannon}$]. | |

| + | *If the source coder considers only the different symbol probabilities, but not the correlation between symbols, then $L_{\rm M} ≥ H_1$ ⇒ [[Information_Theory/Sources with Memory#Entropy with respect to two-tuples|$\text{first entropy approximation}$]].}} | ||

| − | |||

| + | {{GraueBox|TEXT= | ||

| + | $\text{Example 7:}$ | ||

| + | For a quaternary source with the symbol probabilities | ||

| + | |||

| + | :$$p_{\rm A} = 2^{-1}\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}p_{\rm B} = 2^{-2}\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}p_{\rm C} = p_{\rm D} = 2^{-3} | ||

| + | \hspace{0.3cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} H = H_1 = 1.75\,\, {\rm bit/source\hspace{0.15cm} symbol} $$ | ||

| − | + | equality in the above equation ⇒ $L_{\rm M} = H$ results, if for example the following assignment is chosen: | |

| + | |||

| + | :$$\boldsymbol{\rm A } \hspace{0.15cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.15cm} 0 | ||

| + | \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}\boldsymbol{\rm B } \hspace{0.15cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.15cm} 10 | ||

| + | \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}\boldsymbol{\rm C} \hspace{0.15cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.15cm} 110 | ||

| + | \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}\boldsymbol{\rm D }\hspace{0.15cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.15cm} 111 | ||

| + | \hspace{0.05cm}. $$ | ||

| + | In contrast, with the same mapping and | ||

| + | |||

| + | :$$p_{\rm A} = 0.4\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}p_{\rm B} = 0.3\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}p_{\rm C} = 0.2 | ||

| + | \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}p_{\rm D} = 0.1\hspace{0.05cm} | ||

| + | \hspace{0.3cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} H = 1.845\,\, {\rm bit/source\hspace{0.15cm}symbol}$$ | ||

| − | { | + | the average code word length |

| − | + | ||

| + | :$$L_{\rm M} = 0.4 \cdot 1 + 0.3 \cdot 2 + 0.2 \cdot 3 + 0.1 \cdot 3 | ||

| + | = 1.9\,\, {\rm bit/source\hspace{0.15cm}symbol}\hspace{0.05cm}. $$ | ||

| − | + | Because of the unfavorably chosen symbol probabilities (no powers of two) ⇒ $L_{\rm M} > H$.}} | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

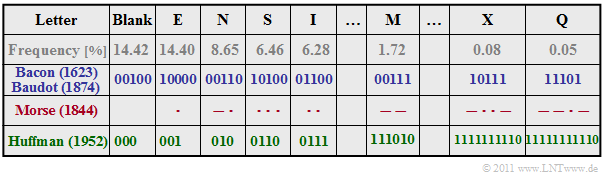

| − | {{ | + | [[File:EN_Inf_T_2_1_S6.png|right|frame|Character encodings according to Bacon/Bandot, Morse and Huffman]] |

| + | {{GraueBox|TEXT= | ||

| + | $\text{Example 8:}$ | ||

| + | We will look at some very early attempts at source encoding for the transmission of natural texts, based on the letter frequencies given in the table. | ||

| + | *In the literature many different frequencies are found, also because, the investigations were carried out for different languages. | ||

| + | *Mostly, however, the list starts with the blank and "E" and ends with letters like "X", "Y" and "Q". | ||

| + | <br clear=all> | ||

| + | Please note the following about this table: | ||

| + | *The entropy of this alphabet with $M = 27$ characters will be $H≈ 4 \, \rm bit/character$. We have only estimated this value. [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Bacon $\text{Francis Bacon}$] had already given a binary code in 1623, where each letter is represented by five bits: $L_{\rm M} = 5$. | ||

| + | *About 250 years later [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baudot_code $\text{Jean-Maurice-Émile Baudot}$] adopted this code, which was later standardized for the entire telegraphy. One consideration important to him was that a code with a uniform five binary characters per letter is more difficult for an enemy to decipher, since he cannot draw conclusions about the transmitted character from the frequency of its occurrence. | ||

| + | *The last line in the above table gives an exemplary [[Information_Theory/Entropy_Coding_According_to_Huffman#The_Huffman_algorithm|$\text{Huffman code}$]] for the above frequency distribution. Probable characters like "E" or "N" and also the "Blank" are represented with three bits only, the rare "Q" on the other hand with eleven bits. | ||

| + | *The average code word length $L_{\rm M} = H + ε$ is slightly larger than $H$, whereby we will not go into more detail here about the small positive quantity $ε$. Only this much: There is no prefix-free code with smaller average word length than the Huffman code. | ||

| + | *Also [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Morse_code $\text{Samuel Morse}$] took into account the different frequencies in his code for telegraphy, already in the 1830s. The Morse code of each character consists of two to four binary characters, which are designated here according to the application with dot ("short") and bar ("long"). | ||

| + | *It is obvious that for the Morse code $L_{\rm M} < 4$ will apply, according to the penultimate line. But this is connected with the fact that this code is not prefix-free. Therefore, the radio operator had to take a break between each "short-long" sequence so that the other station could decode the radio signal as well.}} | ||

| − | == Aufgaben | + | == Exercises for the chapter== |

| + | <br> | ||

| + | [[Aufgaben:Exercise_2.1:_Coding_with_and_without_Loss|Exercise 2.1: Coding with and without Loss]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Aufgaben:Exercise_2.2:_Kraft–McMillan_Inequality|Exercise 2.2: Kraft–McMillan Inequality]] | ||

| + | [[Aufgaben:Exercise_2.2Z:_Average_Code_Word_Length|Exercise 2.2Z: Average Code Word Length]] | ||

{{Display}} | {{Display}} | ||

Latest revision as of 16:18, 19 February 2023

Contents

- 1 # OVERVIEW OF THE SECOND MAIN CHAPTER #

- 2 Source coding - Channel coding - Line coding

- 3 Lossy source coding for images

- 4 Lossy source coding for audio signals

- 5 MPEG-2 Audio Layer III - short "MP3"

- 6 Description of lossless source encoding – Requirements

- 7 Kraft–McMillan inequality - Prefix-free codes

- 8 Source coding theorem

- 9 Exercises for the chapter

# OVERVIEW OF THE SECOND MAIN CHAPTER #

Shannon's Information Theory is applied, for example, in the »Source coding« of digital (i.e. discrete and discrete-time) message sources. In this context, one also speaks of »Data compression«.

- Attempts are made to reduce the redundancy of natural digital sources such as measurement data, texts, or voice and image files (after digitization) by recoding them, so that they can be stored and transmitted more efficiently.

- In most cases, source encoding is associated with a change of the symbol set size. in the following, the output sequence is always binary.

The following is a detailed discussion of:

- The different destinations of »source coding«, »channel coding« and »line coding«,

- »lossy encoding methods« for analog sources, for example GIF, TIFF, JPEG, PNG, MP3,

- the »source encoding theorem«, which specifies a limit for the average code word length,

- the frequently used data compression according to »Lempel, Ziv and Welch«,

- the »Huffman code« as the best known and most efficient form of entropy coding,

- the »Shannon-Fano code« as well as the »arithmetic coding« - both belong to the class of entropy encoders as well,

- the »run-length coding« (RLC) and the »Burrows-Wheeler transformation« (BWT).

Source coding - Channel coding - Line coding

For the descriptions in this second chapter we consider the following model of a digital transmission system:

- The source signal $q(t)$ can be analog as well as digital, just like the sink signal $v(t)$. All other signals in this block diagram, even those not explicitly named here, are digital.

- In particular, also the signals $x(t)$ and $y(t)$ at the input and output of the "digital channel" are digital and can therefore also be described completely by the symbol sequences $〈x_ν〉$ and $〈y_ν〉$.

- The "digital channel" includes not only the transmission medium and interference (noise) but also components of the transmitter $($modulator, transmitter pulse shaper, etc.$)$ and the receiver $($demodulator, receiver filter, detector, decision$)$.

- The chapter "Parameters of Digital Channel Models" in the book "Digital Signal Transmission" describes the modeling of the "digital channel".

As can be seen from this block diagram, there are three different types of coding, depending on the target direction. Each of which is realized by the "encoder" on the transmission side and the corresponding "decoder" at the receiver:

⇒ Task of the »source coding« is the reduction of redundancy for data compression, as it is used for example in image coding. By using correlations between the individual points of an image or between the brightness values of a pixel at different times (for moving picture sequences) procedures can be developed which lead to a noticeable reduction of the amount of data (measured in bit or byte) with nearly the same picture quality. A simple example is the »differential pulse code modulation« (DPCM).

⇒ With »channel coding« on the other hand, a noticeable improvement of the transmission behavior is achieved by using a redundancy specifically added at the transmitter to detect and correct transmission errors at the receiver side. Such codes, whose most important representatives are »block codes«, »convolutional codes« and »turbo codes«, are of great importance, especially for heavily disturbed channels. The greater the relative redundancy of the encoded signal, the better the correction properties of the code, but at a reduced payload data rate.

⇒ »Line coding« is used to adapt the transmitted signal $x(t)$ to the spectral characteristics of the channel and the receiving equipment by recoding the source symbols. For example, in the case of an (analog) transmission channel over which no direct signal can be transmitted, for which thus $H_{\rm K}(f = 0) = 0$, it must be ensured by line coding that the encoded sequence does not contain long sequences of the same polarity.

The focus of this chapter is on lossless source coding, which generates a data-compressed encoded sequence $〈c_ν〉$ starting from the source symbol sequence $〈q_ν〉$ and based on the results of information theory.

- Channel coding is the subject of a separate book in our tutorial with the following $\text{content}$ .

- The channel coding is discussed in detail in the chapter "Coded and multilevel transmission" of the book "Digital Signal Transmission" .

Note: We uniformly use "$\nu$" here as a control variable of a symbol sequence. Normally, for $〈q_ν〉$, $〈c_ν〉$ and $〈x_ν〉$ different indices should be used if the rates do not match.

Lossy source coding for images

For digitizing analog source signals such as speech, music or pictures, only lossy source coding methods can be used. Even the storage of a photo in $\text{BMP}$ format is always associated with a loss of information due to sampling, quantization and the finite color depth.

However, there are also a number of compression methods for images that result in much smaller image files than "BMP", for example:

- $\text{GIF}$ ("Graphics Interchange Format"), developed by Steve Wilhite in 1987.

- $\text{JPEG}$ - a format that was introduced in 1992 by the "Joint Photography Experts Group" and is now the standard for digital cameras. Ending: "jpeg" or "jpg".

- $\text{TIFF}$ ("Tagged Image File Format"), around 1990 by Aldus Corp. (now Adobe) and Microsoft, still the quasi-standard for print-ready images of the highest quality.

- $\text{PNG}$ ("Portable Network Graphics"), designed in 1995 by T. Boutell and T. Lane as a replacement for the patent-encumbered GIF format, is less complex than TIFF.

These compression methods partly use

- vector quantization for redundancy reduction of correlated pixels,

- at the same time the lossless compression algorithms according to $\text{Huffman}$ and $\text{Lempel/Ziv}$,

- possibly also transformation coding based on DFT ("Discrete Fourier Transform") and DCT ("Discrete Cosine Transform"),

- then quantization and transfer in the transformed range.

We now compare the effects of two compression methods on the subjective quality of photos and graphics, namely:

- $\rm JPEG$ $($with compression factor $8)$, and

- $\rm PNG$ $($with compression factor $24)$.

$\text{Example 1:}$ In the upper part of the graphic you can see two compressions of a photo.

The format $\rm JPEG$ (left image) allows a compression factor of $8$ to $15$ with (nearly) lossless compression.

- Even with the compression factor $35$ the result can still be called "good".

- For most consumer digital cameras, "JPEG" is the default storage format.

The image shown on the right was compressed with $\rm PNG$.

- The quality is similar to the JPEG result, although the compression is about $3$ stronger.

- In contrast, PNG achieves a worse compression result than JPEG if the photo contains a lot of color gradations.

PNG is also better suited for line drawings with captions than JPEG (compare the lower images).

- The quality of the JPEG compression (on the left) is significantly worse than the PNG result, although the resulting file size is about three times as large.

- Especially fonts look "washed out".

Note: Due to technical limitations of $\rm LNTwww$ all graphics had to be saved as "PNG".

- In the above graphic, "JPEG" means the PNG conversion of a file previously compressed with "JPEG".

- However, the associated loss is negligible.

Lossy source coding for audio signals

A first example of source coding for speech and music is the "pulse-code modulation" $\rm (PCM)$, invented in 1938, which extracts the encoded sequence $〈c_ν〉 $ from an analog source signal $q(t)$, corresponding to the three processing blocks

- Sampling,

- Quantization,

- PCM encoding.

The graphic illustrates the PCM principle. A detailed description of the picture can be found on the first sections of the chapter "Pulse-code modulation" in the book "Modulation Methods".

Because of the necessary band limitation and quantization, this transformation is always lossy. That means

- The encoded sequence $〈c_ν〉$ has less information than the source signal $q(t)$.

- The sink signal $v(t)$ is fundamentally different from $q(t)$.

- Mostly, however, the deviation is not very large.

We will now mention two transmission methods based on pulse code modulation as examples.

$\text{Example 2:}$ The following data is taken from the $\text{GSM specification}$:

- If a speech signal is spectrally limited to the bandwidth $B = 4 \, \rm kHz$ ⇒ sampling rate $f_{\rm A} = 8 \, \rm kHz$ with a quantization of $13 \, \rm bit$ ⇒ number of quantization levels $M = 2^{13} = 8192$ a binary data stream of data rate $R = 104 \, \rm kbit/s$ results.

- The quantization noise ratio is then $20 \cdot \lg M ≈ 78 \, \rm dB$.

- For quantization with $16 \, \rm bit$ this increases to $96 \, \rm dB$. At the same time, however, the required data rate increases to $R = 128 \, \rm kbit/s$.

The following (German language) interactive SWF applet illustrates the effects of a bandwidth limitation:

"Einfluss einer Bandbegrenzung bei Sprache und Musik" ⇒ "Impact of a Bandwidth Limitation for Speech and Music" .

$\text{Example 3:}$ The standard $\text{ISDN}$ ("Integrated Services Digital Network") for telephony via two-wire line is also based on the PCM principle, whereby each user is assigned two B-channels (Bearer Channels ) with $64 \, \rm kbit/s$ ⇒ $M = 2^{8} = 256$ and a D-channel (Data Channel ) with $ 16 \, \rm kbit/s$.

- The net data rate is thus $R_{\rm net} = 144 \, \rm kbit/s$.

- In consideration of the channel coding and the control bits (required for organizational reasons), the ISDN gross data rate of $R_{\rm gross} = 192 \, \rm kbit/s$.

In mobile communications, very high data rates often could not (yet) be handled. In the 1990s, speech coding procedures were developed that led to data compression by the factor $8$ and more. From today's point of view, it is worth mentioning:

- The $\text{Enhanced Full Rate Codec}$ $\rm (EFR)$, which extracts exactly $244 \, \rm bit$ for each speech frame of $20\, \rm ms$ $($Data rate: $12. 2 \, \rm kbit/s)$;

this data compression of more than the factor $8$ is achieved by stringing together several procedures:

- Linear Predictive Coding $\rm (LPC$, short term prediction$)$,

- Long Term Prediction $\rm (LTP)$,

- Regular Pulse Excitation $\rm (RPE)$.

- The $\text{Adaptive Multi Rate Codec}$ $\rm (AMR)$ based on $\rm ACELP$ ("Algebraic Code Excited Linear Prediction") and several modes between $12. 2 \, \rm kbit/s$ $\rm (EFR)$ and $4.75 \, \rm kbit/s$ so that improved channel coding can be used in case of poorer channel quality.

- The $\text{Wideband-AMR}$ $\rm (WB-AMR)$ with nine modes between $6.6 \, \rm kbit/s$ and $23.85 \, \rm kbit/s$. This is used with $\text{UMTS}$ and is suitable for broadband signals between $200 \, \rm Hz$ and $7 \, \rm kHz$. Sampling is done with $16 \, \rm kHz$, quantization with $4 \, \rm bit$.

All these compression methods are described in detail in the chapter "Speech Coding" of the book "Examples of Communication Systems" The (German language) audio module "Qualität verschiedener Sprach-Codecs" ⇒ "Quality of different voice codecs" allows a subjective comparison of these codecs.

MPEG-2 Audio Layer III - short "MP3"

Today (2015) the most common compression method for audio files is $\text{MP3}$. This format was developed from 1982 on at the Fraunhofer Institute for Integrated Circuits (IIS) in Erlangen under the direction of Professor $\text{Hans-Georg Musmann}$ in collaboration with the Friedrich Alexander University Erlangen-Nuremberg and AT&T Bell Labs. Other institutions are also asserting patent claims in this regard, so that since 1998 various lawsuits have been filed which, to the authors' knowledge, have not yet been finally concluded.

In the following some measures are called, which are used with "MP3", in order to reduce the data quantity in relation to the raw version in the $\text{wav}$-format. The compilation is not complete. A comprehensive representation about this can be found for example in a $\text{Wikipedia article}$.

- The audio compression method "MP3" uses among other things psychoacoustic effects of perception. So a person can only distinguish two sounds from each other from a certain minimum difference in pitch. One speaks of so-called "masking effects".

- Using the masking effects, signal components that are less important for the auditory impression are stored with less bits (reduced accuracy). A dominant tone at $4 \, \rm kHz$ can, for example, cause neighboring frequencies to be of only minor importance for the current auditory sensation up to $11 \, \rm kHz$.

- The greatest advantage of MP3 coding, however, is that the sounds are stored with just enough bits so that the resulting $\text{quantization noise}$ is still masked and is not audible.

- Other MP3 compression mechanisms are the exploitation of the correlations between the two channels of a stereo signal by difference formation as well as the $\text{Huffman Coding}$ of the resulting data stream. Both measures are lossless.

A disadvantage of the MP3 coding is that with strong compression also "important" frequency components are unintentionally captured and thus audible errors occur. Furthermore it is disturbing that due to the blockwise application of the MP3 procedure gaps can occur at the end of a file. A remedy is the use of the so-called $\text{LAME coder}$ and a corresponding player.

Description of lossless source encoding – Requirements

In the following, we only consider lossless source coding methods and make the following assumptions:

- The digital source has the symbol set size $M$. For the individual source symbols of the sequence $〈q_ν〉$ applies with the symbol set $\{q_μ\}$:

- $$q_{\nu} \in \{ q_{\mu} \}\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}\mu = 1, \hspace{0.05cm}\text{...} \hspace{0.05cm}, M \hspace{0.05cm}. $$

The individual sequence elements $q_ν$ may can be "statistically independent" or "statistically dependent".

- First we consider »discrete sources without memory«, which are fully characterized by the symbol probabilities alone, for example:

- $$M = 4\text{:} \ \ \ q_μ \in \{ {\rm A}, \ {\rm B}, \ {\rm C}, \ {\rm D} \}, \hspace{3.0cm} \text{with the probabilities}\ p_{\rm A},\ p_{\rm B},\ p_{\rm C},\ p_{\rm D},$$

- $$M = 8\text{:} \ \ \ q_μ \in \{ {\rm A}, \ {\rm B}, \ {\rm C}, \ {\rm D},\ {\rm E}, \ {\rm F}, \ {\rm G}, \ {\rm H} \}, \hspace{0.5cm} \text{with the probabilities }\ p_{\rm A},\hspace{0.05cm}\text{...} \hspace{0.05cm} ,\ p_{\rm H}.$$

- The source encoder replaces the source symbol $q_μ$ with the code word $\mathcal{C}(q_μ)$,

consisting of $L_μ$ code symbols of a new alphabet with the symbol set size $D$ $\{0, \ 1$, ... , $D - 1\}$. This gives the »average code word length«:

- $$L_{\rm M} = \sum_{\mu=1}^{M} \hspace{0.1cm} p_{\mu} \cdot L_{\mu} \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}{\rm with} \hspace{0.2cm}p_{\mu} = {\rm Pr}(q_{\mu}) \hspace{0.05cm}. $$

$\text{Example 4:}$ We consider two different types of source encoding, each with parameters $M = 9$ and $D = 3$.

- In the first encoding $\mathcal{C}_1(q_μ)$ according to line 2 (red) of the table, each source symbol $q_μ$ is replaced by two ternary symbols $(0$, $1$ or $2)$. Here we have for example the mapping:

- $$\rm A C F B I G \ ⇒ \ 00 \ 02 \ 12 \ 01 \ 22 \ 20.$$

- With this coding, all code words $\mathcal{C}_1(q_μ)$ with $1 ≤ μ ≤ 6$ have the same length $L_μ = 2$. Thus, the average code word length is $L_{\rm M} = 2$.

- For the second, the blue source encoder holds $L_μ ∈ \{1, 2 \}$. Accordingly, the average code word length $L_{\rm M}$ will be less than two code symbols per source symbol. For example, the mapping:

- $$\rm A C F B I G \ ⇒ \ 0 \ 02 \ 12 \ 01 \ 22 \ 2.$$

- It is obvious that this encoded sequence cannot be decoded unambiguously, since the symbol sequence naturally does not include the spaces inserted in this text for display reasons.

Kraft–McMillan inequality - Prefix-free codes

Binary codes for compressing a memoryless discrete source are characterized by the fact that the individual symbols are represented by encoded sequences of different lengths:

- $$L_{\mu} \ne {\rm const.} \hspace{0.4cm}(\mu = 1, \hspace{0.05cm}\text{...} \hspace{0.05cm}, M ) \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

Only then it is possible,

- that the average code word length becomes minimal,

- if the source symbols are not equally probable.

To enable a unique decoding, the code must also be "prefix-free".

$\text{Definition:}$ The property »prefix-free« indicates that no code word may be the prefix (beginning) of a longer code word. Such a code word is immediately decodable.

- The blue code in $\text{Example 4}$ is not prefix-free. For example, the encoded sequence "01" could be interpreted by the decoder as $\rm AD$ but also as $\rm B$.

- The red code, on the other hand, is prefix-free, although prefix freedom would not be absolutely necessary here because of $L_μ = \rm const.$

$\text{Without proof:}$ The necessary »condition for the existence of a prefix-free code« was specified by Leon Kraft in his Master Thesis 1949 at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT):

- $$\sum_{\mu=1}^{M} \hspace{0.2cm} D^{-L_{\mu} } \le 1 \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

$\text{Example 5:}$ If you check the second (blue) code of $\text{Example 4}$ with $M = 9$ and $D = 3$, you get:

- $$3 \cdot 3^{-1} + 6 \cdot 3^{-2} = 1.667 > 1 \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

From this you can see that this code cannot be prefix-free.

$\text{Example 6:}$ Let's now look at the binary code

- $$\boldsymbol{\rm A } \hspace{0.15cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.15cm} 0 \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}\boldsymbol{\rm B } \hspace{0.15cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.15cm} 00 \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}\boldsymbol{\rm C } \hspace{0.15cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.15cm} 11 \hspace{0.05cm}, $$

it is obviously not prefix-free. The equation

- $$1 \cdot 2^{-1} + 2 \cdot 2^{-2} = 1 $$

does not mean that this code is actually prefix-free, it just means that there is a prefix-free code with the same length distribution, for example

- $$\boldsymbol{\rm A } \hspace{0.15cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.15cm} 0 \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}\boldsymbol{\rm B } \hspace{0.15cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.15cm} 10 \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}\boldsymbol{\rm C } \hspace{0.15cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.15cm} 11 \hspace{0.05cm}.$$

Source coding theorem

We now look at a redundant discrete source with the symbol set $〈q_μ〉$, where the control variable $μ$ takes all values between $1$ and the symbol set size $M$. The source entropy $H$ is smaller than $H_0= \log_2 \hspace{0.1cm} M$.

The redundancy $(H_0- H)$ is either caused by

- not equally probable symbols ⇒ $p_μ ≠ 1/M$, and/or

- statistical bonds within the sequence $〈q_\nu〉$.

A source encoder replaces the source symbol $q_μ$ with the code word $\mathcal{C}(q_μ)$, consisting of $L_μ$ binary symbols (zeros or ones). This results in an average code word length:

- $$L_{\rm M} = \sum_{\mu=1}^{M} \hspace{0.2cm} p_{\mu} \cdot L_{\mu} \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}{\rm with} \hspace{0.2cm}p_{\mu} = {\rm Pr}(q_{\mu}) \hspace{0.05cm}. $$

For the source encoding task described here the following requirement can be specified:

$\text{Theorem:}$ For the possibility of a complete reconstruction of the sent string from the binary sequence it is sufficient, but also necessary, that for encoding on the transmitting side at least $H$ binary symbols per source symbol are used.

- The average code word length $L_{\rm M}$ cannot be smaller than the entropy $H$ of the source symbol sequence: $L_{\rm M} \ge H \hspace{0.05cm}. $

- This regularity is called »Source Coding Theorem«, which goes back to $\text{Claude Elwood Shannon}$.

- If the source coder considers only the different symbol probabilities, but not the correlation between symbols, then $L_{\rm M} ≥ H_1$ ⇒ $\text{first entropy approximation}$.

$\text{Example 7:}$ For a quaternary source with the symbol probabilities

- $$p_{\rm A} = 2^{-1}\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}p_{\rm B} = 2^{-2}\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}p_{\rm C} = p_{\rm D} = 2^{-3} \hspace{0.3cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} H = H_1 = 1.75\,\, {\rm bit/source\hspace{0.15cm} symbol} $$

equality in the above equation ⇒ $L_{\rm M} = H$ results, if for example the following assignment is chosen:

- $$\boldsymbol{\rm A } \hspace{0.15cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.15cm} 0 \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}\boldsymbol{\rm B } \hspace{0.15cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.15cm} 10 \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}\boldsymbol{\rm C} \hspace{0.15cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.15cm} 110 \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}\boldsymbol{\rm D }\hspace{0.15cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.15cm} 111 \hspace{0.05cm}. $$

In contrast, with the same mapping and

- $$p_{\rm A} = 0.4\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}p_{\rm B} = 0.3\hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}p_{\rm C} = 0.2 \hspace{0.05cm}, \hspace{0.2cm}p_{\rm D} = 0.1\hspace{0.05cm} \hspace{0.3cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.3cm} H = 1.845\,\, {\rm bit/source\hspace{0.15cm}symbol}$$

the average code word length

- $$L_{\rm M} = 0.4 \cdot 1 + 0.3 \cdot 2 + 0.2 \cdot 3 + 0.1 \cdot 3 = 1.9\,\, {\rm bit/source\hspace{0.15cm}symbol}\hspace{0.05cm}. $$

Because of the unfavorably chosen symbol probabilities (no powers of two) ⇒ $L_{\rm M} > H$.

$\text{Example 8:}$ We will look at some very early attempts at source encoding for the transmission of natural texts, based on the letter frequencies given in the table.

- In the literature many different frequencies are found, also because, the investigations were carried out for different languages.

- Mostly, however, the list starts with the blank and "E" and ends with letters like "X", "Y" and "Q".

Please note the following about this table:

- The entropy of this alphabet with $M = 27$ characters will be $H≈ 4 \, \rm bit/character$. We have only estimated this value. $\text{Francis Bacon}$ had already given a binary code in 1623, where each letter is represented by five bits: $L_{\rm M} = 5$.

- About 250 years later $\text{Jean-Maurice-Émile Baudot}$ adopted this code, which was later standardized for the entire telegraphy. One consideration important to him was that a code with a uniform five binary characters per letter is more difficult for an enemy to decipher, since he cannot draw conclusions about the transmitted character from the frequency of its occurrence.

- The last line in the above table gives an exemplary $\text{Huffman code}$ for the above frequency distribution. Probable characters like "E" or "N" and also the "Blank" are represented with three bits only, the rare "Q" on the other hand with eleven bits.

- The average code word length $L_{\rm M} = H + ε$ is slightly larger than $H$, whereby we will not go into more detail here about the small positive quantity $ε$. Only this much: There is no prefix-free code with smaller average word length than the Huffman code.

- Also $\text{Samuel Morse}$ took into account the different frequencies in his code for telegraphy, already in the 1830s. The Morse code of each character consists of two to four binary characters, which are designated here according to the application with dot ("short") and bar ("long").

- It is obvious that for the Morse code $L_{\rm M} < 4$ will apply, according to the penultimate line. But this is connected with the fact that this code is not prefix-free. Therefore, the radio operator had to take a break between each "short-long" sequence so that the other station could decode the radio signal as well.

Exercises for the chapter

Exercise 2.1: Coding with and without Loss

Exercise 2.2: Kraft–McMillan Inequality

Exercise 2.2Z: Average Code Word Length